The field of outsider art, or art brut as it is better known in Europe, has always been riddled with more questions than canonical certainties. The insider/ outsider distinction; the political correctness of the term; and notions of high and low art are just a few issues that continue to vex those who study and collect outsider art.

While there may never be a definition of outsider art that satisfies everyone, there is a place that demonstrates what it is in the small Austrian town of Klosterneuburg just northwest of Vienna: the Art Brut Center Gugging. There the making of art is fused to mental health treatment, and artist-patients enjoy the benefits of a sophisticated exhibition and marketing apparatus.

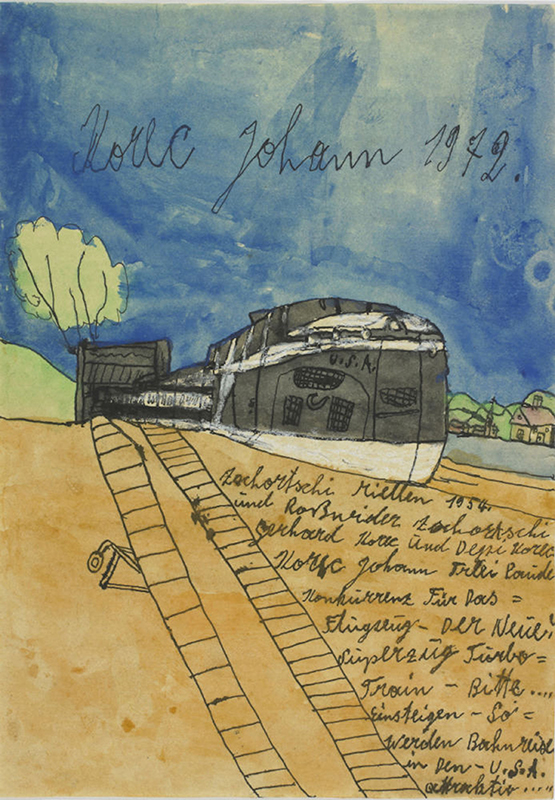

The Maria Gugging Psychiatric Clinic was founded in 1889. The facility’s genesis as an art brut center began in 1954, when one of its psychiatrists, Leo Navratil (1921–2006), started to employ a draw-a-person test as a diagnostic aid, inspired by the 1949 book Personality Projection in the Drawing of the Human Figure by Karen Machover. Applying a nonverbal measure to personality assessments was not uncommon then, though patients’ drawings were considered strictly ancillary materials and were therefore rarely archived. But Navratil pondered the occasional intriguing drawings his patients produced, and he concluded that they were encrypted products of the mind, and creations that begged to be deciphered and even perhaps admired.

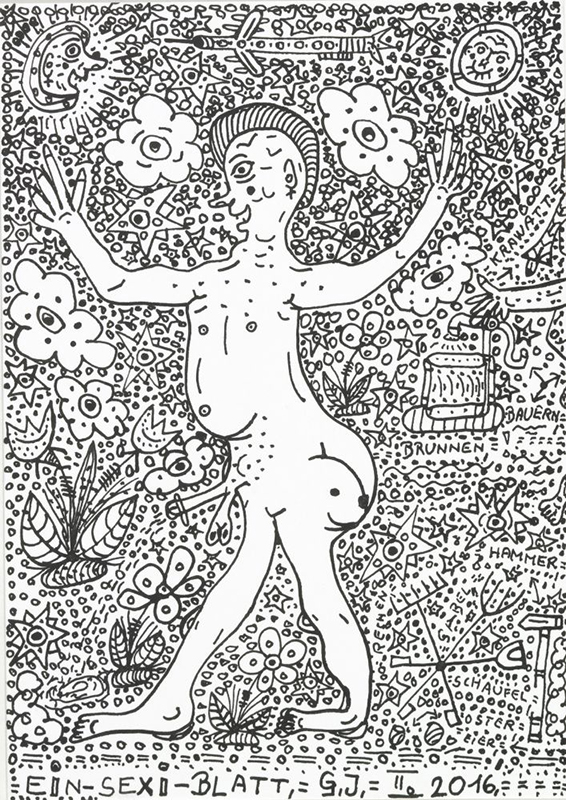

Among the first who impressed Navratil was Johann Hauser. A long-time patient at the clinic, he was an orphan who was never able to read and write, and, as a young man, was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Hauser chose colored pencils as his medium and most frequently drew female figures—some clothed, some nude, some demure, some demonic, all exuding erotic energy. He was said to have drawn in a manner that paralleled his mental state: exuberant and explosive during his manic phase; dark and subdued during his depressive state. The profundity of such cases led Navratil to believe that the patient’s creativity was largely a manifestation of his mental condition—zustandsgebundene Kunst (“state-bound art”), he called it. Today, those who study art brut place far more emphasis on individual creativity than pathology.

When Navratil published his book Schizophrenia and Art in 1965, informed by his own observations and seminal earlier texts such as Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922) by Hans Prizorn, accolades came not from the world of psychiatry, but from the Viennese avant-garde—mainly visual artists like André Heller, Peter Pongratz, and Arnulf Rainer. Enthused, they soon became Gugging’s most ardent supporters, helping Navratil take what he had unearthed into the public realm. (And even won Gugging celebrity cachet. In 1994, Heller invited his musician pals Brian Eno and David Bowie to Gugging, occasioning a three-hour visit that would become the primary source of inspiration for Bowie’s nineteenth and longest studio album, Outside.) The famed artist Jean Dubuffet declared the works from Gugging definitive examples of art brut, a term he coined for “raw art” created outside of the contrived conventions of culture, unaffected by intellectual and aesthetic concerns, solely guided by an unmediated urge to create. To Dubuffet, such was the purest and truest mode of artistic creation.

The first public selling exhibition of drawings from Gugging was held at Vienna’s legendary Galerie nächst St. Stephan in 1970, and the show was a success in both critical reception and sales. Soon afterward, Navratil began an effort to provide a better living and working environment for his artist-patients, as they had become known, whose creativity certainly did not benefit from the austere conditions of the ward at that time. Finally, in 1981, the Centre for Art and Psychotherapy was established in an autonomous building on the outer edge of the Gugging hospital grounds, providing dwellings and dedicated work space to eighteen of the now-famous original “Guggingers”: among them Hauser, Johann Garber, Johann Korec, and Oswald Tschirtner. They were joined a couple of years later by August Walla, who invented a polytheistic cosmos that he delineated in mediums that ranged from painting, drawing, and sculpture to photography and markmaking on buildings, trees, and just about any objects he laid his hands on.

Upon Navratil’s retirement in 1986, Johann Feilacher, who had come to Gugging three years prior to assist Navratil, was named his successor. At his initiative, artistpatients started expressing their creative impulses on the exterior of the building they occupied. One of the very first things Feilacher did in his new post was to rename the Centre for Art and Psychotherapy the House of Artists, a change that signified a new direction under which the artistpatients would simply be regarded as artists. The new firebrand director had a vision to raise Gugging artists to the same level of esteem enjoyed by their modern and contemporary counterparts. “The quality of their work made me certain that this was achievable,” Feilacher once wrote. “I believed it was an equal art, which could be put on an equal plane with that of Miró, Picasso, or Schiele.”*

“Equal” would be the key word. Under new leadership, Gugging sought to champion its artists by presenting their work simply as art, and not a lesser subgenre. “The patriarchal organization under Professor Navratil who represented a father figure has been changed into a group system,” Feilacher added. “Relationships are no longer determined by the doctor-patient paradigm, but we see ourselves as helpers who take care of all those things that the patients can’t accomplish for themselves. I therefore regard myself more as the Artists’ assistant than as their leader.”

Feilacher not only wanted to promote the art of Gugging, he wanted to sell it directly. Demand, he believed, was a measure of appreciation. “By purchasing pieces from Gugging artists, museums were admitting that the works were of equal quality to those by artists without a psychiatry diagnosis.” And selling their art meant the artists could benefit financially from their output. The ensuing years witnessed the inclusion of Gugging artists in various exhibitions across Europe; Walla even had a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in Vienna in the late 1980s. And in 1990, Artists from Gugging—the collective term most frequently used today— were awarded the prestigious Oskar Kokoschka Preis for their contribution to the contemporary art field.

Galerie Gugging opened its doors in 1997, turning a disused children’s psychiatric clinic into a dedicated space that presents, sells, and archives the art of Gugging, much like a traditional art gallery. “The main goal is to promote the works of the Gugging artists worldwide in the field of art, not just Art Brut,” says Nina Katschnig, the gallery’s director since 2000. “We want [the artists] to be seen and respected in the art world. And for them to enjoy their success as any other artists while they are living.”

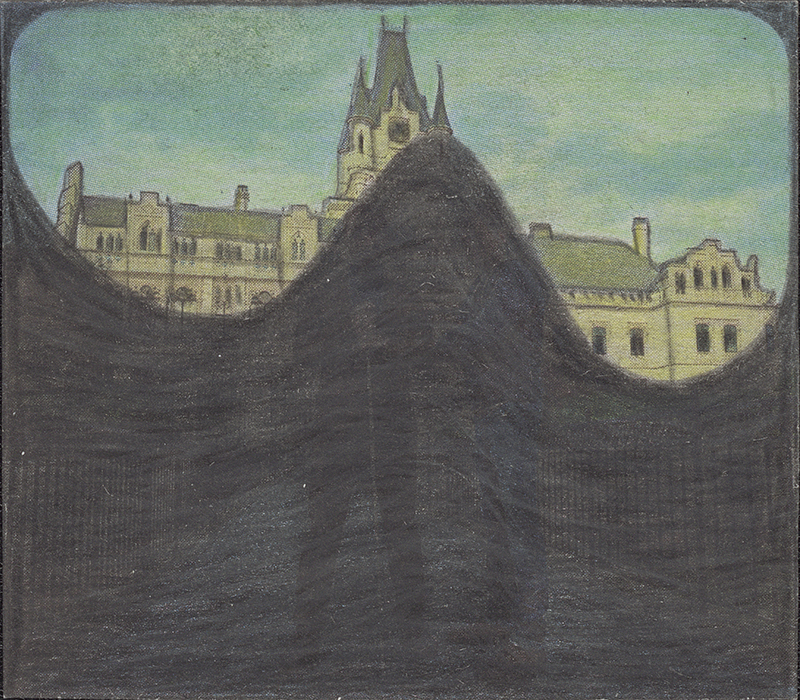

The addition of the gallery enterprise has also allowed Gugging to dovetail its efforts with those of other pioneering champions of art brut around the globe, such as the Galerie St. Etienne and the Ricco/Maresca Gallery in New York, which has represented Artists from Gugging in the US since 2011. Among innumerable accomplishments yielded by the collaborative effort to introduce Gugging to a broader audience, the most notable to date is New York’s Museum of Modern Art’s 2018 acquisition of five drawings by Leopold Strobl, whose virtuosic process of obscuring elements in newsprint images with dark, sinuous graphite masses offers an idiosyncratic approach to abstraction and planar depth. His stylistic eloquence and mastery have helped catapult his status upward in just five short years since his solo debut at Ricco/Maresca in 2016, which sold out.

The new millennium marked an especially portentous moment for Gugging: the House of Artists became independent from the hospital. Atelier Gugging was established in 2001 within the House of Artists building— an open studio space that is used not just by the resident artists, but also outside guests. In another step forward, Museum Gugging was founded in 2006 in the same building that houses Galerie Gugging, allowing the institution to mount world-class exhibitions and further expand its audience.

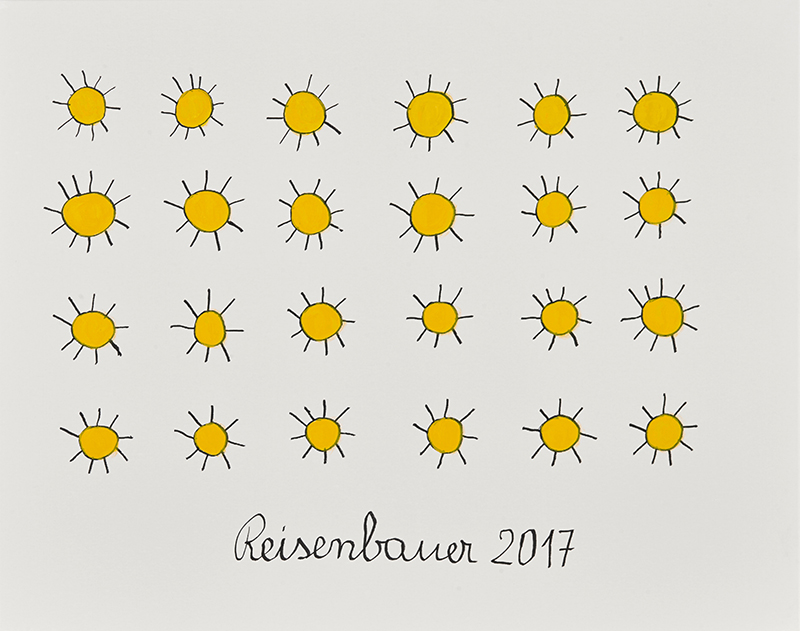

Gugging artists are considered some of the most renowned in the art brut field; their art can be found in a number of significant collections both public and private around the globe. In the world of fashion, designer Christopher Kane has drawn inspiration from artists like Heinrich Reisenbauer and Johann Korec. The House of Artists has become a model for similar workshops in Belgium and Germany.

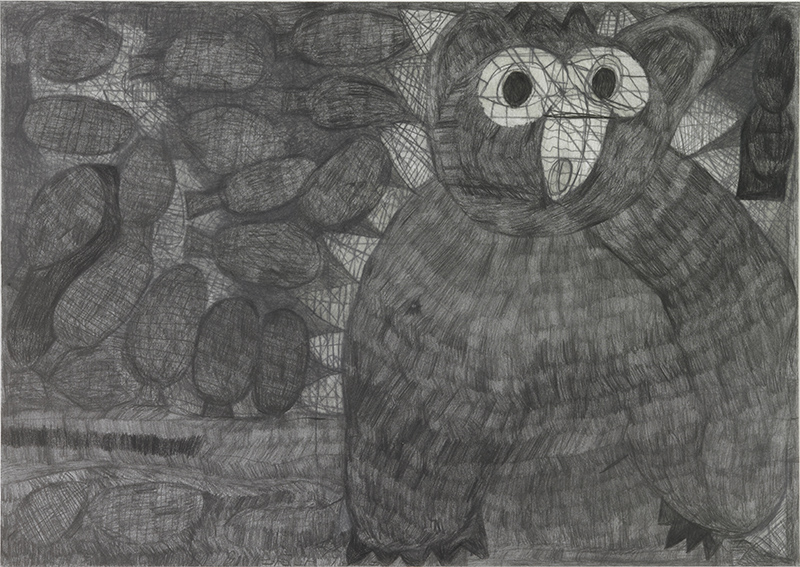

Female artists, long underrepresented in the field of art brut—even at Gugging—are becoming more visible there. Laila Bachtiar, a daily participant in the Gugging open studio program since 2003, uses graphite or colored pencil to create patch-like shapes, which together form a larger image—often abstracted depictions of animals, such as Owl.

To its audience, Gugging offers respite from much of what we see today: art that puts more emphasis on headline-worthiness and less on intrinsic idiosyncrasy. Looking at the disparate yet equally profound works of art produced at Gugging is a spellbinding experience in and of itself. And the seemingly perfect formula the institution has cultivated over time illuminates, in many ways, how we should look at and nurture the innate creativity of those who are unable to articulate it on their own.

KYLIE RYU is the gallery manager at Ricco/Maresca Gallery in New York. She welcomes correspondence about Gugging and its artists at kylie@riccomaresca.com

* Johann Feilacher, Sovären – Das Haus der Künstler in Gugging (Heidelberg: Edition Braus, 2004), pp. 15–17.