Right: Nereid with Confectionary Bowl from the Swan Service for Count Heinrich von Brühl, modeled by Johann Friedrich Eberlein (1695–1749), 1738. © Porcelain Collection, Dresden State Art Collections; photograph by Werner Lieberknecht.

Nearly eighty years since the end of World War II and more than thirty since the fall of the Berlin Wall, Germany remains a work in progress. A first-time visitor, finding many of its noblest structures intact, may never realize that only a few years back they were little more than holes in the ground. A decade ago, two colossal baroque palaces, Berlin’s Königliches Schloss and Potsdam’s Stadtschloss, both inspired by Versailles, were nothing more than faint memories preserved in old photographs. It is a tribute to the indestructibility of architecture, as an embodied formal idea, that both have now been so splendidly and so scrupulously reborn.

Perhaps no German city, however, saw greater destruction than Dresden, not only from Allied bombings in 1945, but also from the Communist regime that followed the collapse of fascism, and that had neither the means nor the inclination to restore the rococo dreams of a repudiated age. Only with the reunification of the country in 1990 were the Zwinger Palace and its surrounding monuments restored to their former splendor.

In the context of the Second World War and its aftermath, there is something especially moving about the fate of Dresden, the capital of Saxony. In the final days of the conflict, on February 13 to 15, 1945, the Allies dropped nearly three thousand tons of incendiary and high explosive bombs on the city, killing as many as twenty-five thousand of its inhabitants. In the process, most of the city, including the Zwinger Palace, was destroyed. But if Dresden, like Munich and Berlin, played a role in the Nazi regime, it was never an important seat of fascism and, indeed, except for a few decades in the first half of the eighteenth century, Dresden was never a major European power. Its one exceptional period of eminence coincided with the reign of Augustus the Strong, elector of Saxony from 1694 to 1733. Notwithstanding his role in the Great Northern War against Charles XII of Sweden, his most lasting contributions were cultural: discovering a way to produce, in Meissen, porcelain as refined as anything from China, and commissioning Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann to design the incomparable Zwinger Palace. Rising beside the Elbe River, this phantasmagoric pile, with its crowned and crested pavilions, its endless arcades festooned with swags and herms, looks like some baroque fever dream that was never supposed to leave the drawing board but somehow did.

Right: Monkey with Grapes, modeled by Kändler, c. 1732. © Porcelain Collection, Dresden State Art Collections; Sauer photograph.

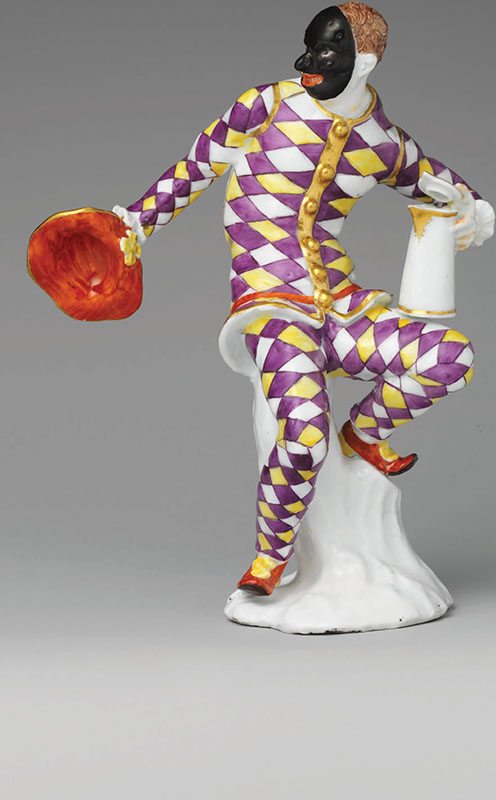

Today a large part of its southern half is home to the Porzellansammlung, or Porcelain Collection, founded by Augustus in 1715. It contains more than twenty thousand examples, not only from Meissen but also from France, Holland, England, Japan, and China. Colorfully reimagined by the American interior designer Peter Marino in 2006, the galleries display famille rose vases, Qing snuff bottles, and Johann Joachim Kändler’s remarkable life-sized porcelain sculptures of swans and goats. It was Kändler, the head of the Meissen factories for much of the eighteenth century, who largely stoked the maladie de porcelaine, that rage for porcelain figurines of swains and maidens, of Harlequins and Columbines, that would conquer Europe and the New World in the ensuing decades.

Although the Zwinger Palace, like most of Dresden, has been spectacularly restored, it is difficult to visit the city today without seeing it from the perspective of the war. In part this is because, as in most regions of Germany, the inhabitants themselves are determined never to forget the events of the middle years of the last century. But it would be a disservice to truth to believe that all of Dresden’s earlier and subsequent history converged on 1945, as though that year were the entire point and ultimate truth of the city’s eight centuries of existence. According to such a reading, the porcelain nymphs and monkeys of the Meissen factories, no less than the rococo extravagances of the Zwinger Palace or the marzipan-laden cakes of the city’s konditereien, are a pleasant, charming, insubstantial and ultimately irrelevant veil thrown over the city’s tragic and ineffaceable heritage. How absurdly paltry, after all, are porcelain and marzipan in comparison with howitzers and concentration camps, how irrelevant, as well, to our own age of reinvigorated political engagement. One is reminded of Theodor Adorno’s famous claim that “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” By implication, that claim seems to reach backwards into earlier culture, as though admiration for these beautiful porcelain trifles represents an obscene indifference to historical truth.

Right: Tureen with Galatea from the Swan Service, modeled by Kändler, 1738. © Porcelain Collection, Dresden State Art Collections; Sauer photograph.

But that point of view itself is a willful misunderstanding, not only of German history but of something fundamental in humanity itself. In its very charm and fragility, a single Meissen figurine is, to be sure, a slight thing. All that the Meissen factories ever produced and continue to produce, taken together, is not a slight thing, but its ultimate importance will be denied by many modern viewers who repudiate its sweet, untroubled worldview in favor of that shriller, more confrontational mood that defines so much of contemporary culture.

In truth, that latter position is no more—and no less—deserving of respect than the worldview that is so magnificently enshrined in the art and architecture and pastry of Dresden. The dominant view of the moment, the one most likely to win respect as “informed” opinion, is overwhelmingly cynical and pessimistic. It sees life on earth, as Hobbes did, as nasty and brutish, if no longer exactly short. It endorses Matthew Arnold’s vision of “a darkling plain,/ Swept with confused alarms of struggle and flight,/ Where ignorant armies clash by night.”

In the face of all of that arises the Meissen figurine, magnificent in its fragile and winsome superfluity. It has brave allies: the rococo palaces of Potsdam and Nymphenburg, the pastries of Paris and Vienna and Prague, the arias of Mozart (and perhaps the Beatles’ greatest hits as well), the very love and pursuit of antiques. Taken together that mass of cultural acts and attitudes must be seen as a powerful riposte to the regnant darkness of the present age. In fact, they are two sides of the same coin, each of them, in its reductivism, insufficient and incomplete. What must be emphasized, however, is that the worldview embodied in a Meissen Harlequin is in every respect evenly matched against the pessimism of the present hour, and it is far more likely to increase the sum total of human happiness.