Josyane and Robert Young, London dealers in European folk art, can often be relied upon to punctuate their traditional material of naïve paintings, love tokens, marriage chests, and trade signs with something unexpected. A few years ago, the entrance to their booth at the Winter Show was framed by two hand-carved limestone figures of a raffish man and woman, each almost five feet tall and weighing nearly three hundred pounds, made who knows why in the mid-nineteenth century. I didn’t have to ask what prompted the Youngs to bring this gigantic couple across the water. I knew it simply represented one more adventure in their exploration of the glorious material culture of the past.

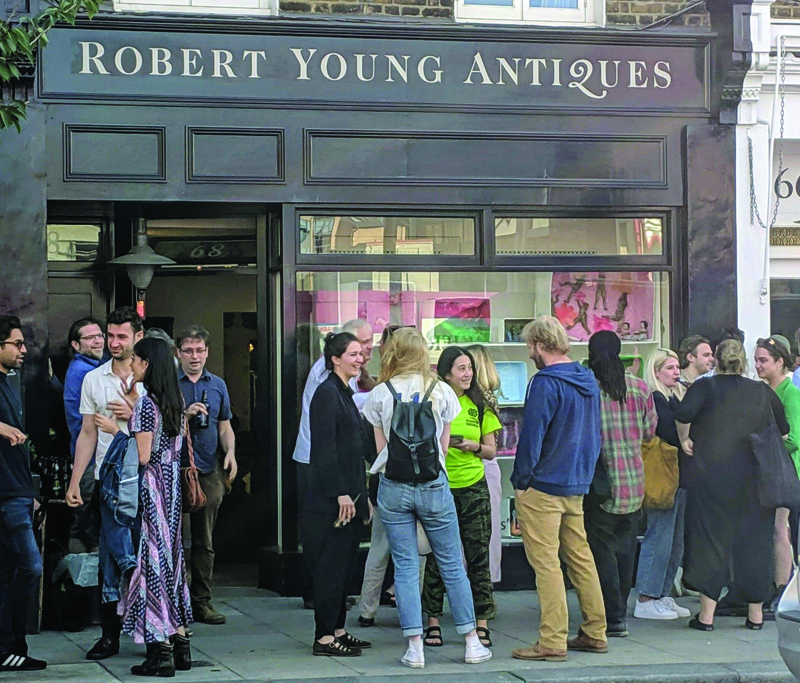

More recently, the couple has broadened their explorations by opening their gallery to contemporary artists, including students at the prestigious Royal College of Art, who submit a project to be featured in the window of Robert Young Antiques. Holding three such exhibitions each year is meant to cross-pollinate the qualities of the antiques in their gallery with the work of emerging contemporary artists, something that prompted me to ask Robert Young a few questions about this intersection of past and present.

I understand that “Contemporary Collaborations” is not primarily a commercial venture. What was the reason?

You’re right, it is not. We pay the artists a subsidy to exhibit and we do all the promotion, printing, and professional photography. However, we have benefited from sponsorship by local brewers and distillers for the opening-night private-view parties to help support the initiative and the artists. It’s great for the local community.

In addition, the artists are permitted to price the works if they choose to, and, if sold, we take a 20 percent commission. In the case of Amba Sayal-Bennett’s work that you are featuring, we did actually sell her pieces.

The reason we don’t stress the commercial side of this program is that we don’t want to muddy the waters. This is not Robert Young Antiques morphing into a contemporary art dealership (as many firms who originally built their galleries and reputations handling antique and historic art have done and are doing). We just want to break down the stigma that old things are now somehow artistically or aesthetically obsolete.

We have been fortunate that the works we handle at RYA have largely been blessed by the contemporary style police, probably because they have a curious compatibility with contemporary and modern works and spaces.

But personally I have always disliked the segregation of old and new, both in museums and commercial galleries. We know that artists have historically been inspired by the works of previous generations and centuries, so it seemed sensible to get young contemporary artists in to look at our collections in a different way and see what elements they found interesting, relevant, exciting, or inspiring. I wanted them to re-contextualize “antiques” and look at old things in a fresh way, simply as combinations of form, colors, textures, and so forth, the elements that make up all art.

How do you choose among the applicants?

We have employed Erin Hughes as our Contemporary Collaborations curator. Erin is an artist, a master’s graduate of the RCA, and passionately involved in the contemporary art world. However, she also has a foot in our camp because when studying at RCA she started to work with us to help pay her fees and other costs. She has a genuine sensitivity to the works we handle and a grasp of the developments in contemporary art. All applications are addressed to her, some she solicits, others come completely out of the blue. She selects a shortlist of typically between three and five proposals, which we then go through together and agree on which artist to select.

The artists have to submit images and a written proposal, including details about which pieces from our collection are most interesting or relevant to them. I don’t judge the works or even claim to understand some of them. I just like them to grab me somehow and to get the feeling that they have really looked at things in our collection and found something worthwhile and inspiring. It’s a gut thing.

In this country there can be an indifference bordering on contempt for the arts of the past, especially among young people. Do you find that to be true in the community of the artists you have featured?

Honestly, no—really, really not. However, the artists we have worked with have often said that the process has changed their attitude toward old things. I guess the ones who have been keen to apply already have some kind of sensitivity to historic material, and of course the RCA master’s degree students are by definition educated, and artistically aware, so maybe not a good random selection of artists. But before we began this initiative, we already had several students a week coming in to explore our collection—some, sketching, others taking photos, some just mooching around and quietly looking but genuinely engaging with the works. Typically it is the more abstract pieces such as the primitive sculptures of the stylized horse and bird-form snuffbox that attract them.

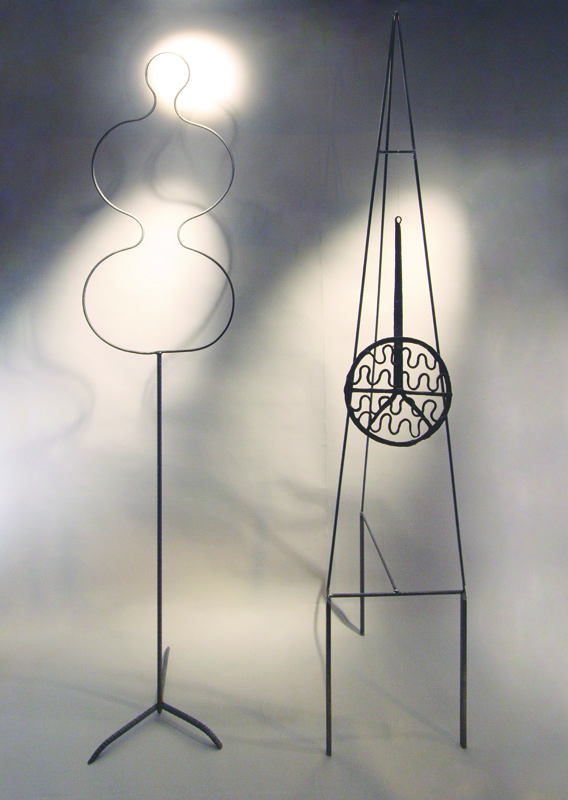

We are showing one of your Contemporary Collaborations, An Unusual Arrangement by Amba Sayal-Bennett. How did this artist engage with the material in your gallery?

Amba was immediately attracted to linear forms and the old oxidized and patinated ferrous metal surfaces. Originally she thought she was going to work around a wrought-iron wine rack that has a wavy repetitive form to its “shelves.” She toyed with a range of other wrought-iron pieces before she discovered the Peerman lighting device, which she felt reflected the human form and had a zoomorphic quality about it. She became increasingly involved with the materiality of the pieces and the way these complicated hand-wrought forms had been fashioned before welding was invented, developing in the process a huge respect for the original makers who were, of course, humble artisans, never “artists.” Kind of my point!

If I confessed to you that, much as I applaud this venture into contemporary art, it has made me appreciate the unselfconscious nature of the traditional material even more, would you be disappointed?

I refer you to my answer of a moment ago, and no, of course I would not and could not be disappointed. The idea was never to measure or judge the merits or qualities of old against new. As a teenager, when I fantasied that I might seek out a life as an artist, I was once completely bowled over by an amazingly worn and patinated rustic piece I saw in an antiques shop window. I thought it was so very cool and also I thought I might be the only person who knew how great it was. But of course it was like it was because of its age. It was not something “makeable”; it just had qualities that only time, use, and wear can bestow on wood. The wonderful arrogance of youth let me believe I’d discovered it, but what I did learn from that moment is that to be “cool” art didn’t have to be modern.

Then I learnt that Henry Moore had been inspired by nature—raw driftwood, ancient rocks with holes in them, sun-bleached bones, all the things that have some kind of past and yet are simply timeless. It’s not a question of choosing between the old and the new, but of seeing the qualities that animate them both.

What surprised you most about these collaborations? What have you learned?

I think the surprise has really been in the response we’ve encountered. I anticipated artists wanting to create something outside their normal practice but I hadn’t anticipated how many of them would be eager to be included in Contemporary Collaborations.

I don’t know how many of our traditional clients have embraced the project, but some have been intrigued (one bought one of the works), some have been genuinely complimentary, others just critical. All of which means it is working.

When I said it was not a commercial initiative, I meant it. I simply wanted to explore. I’m loving the journey. Perhaps we will discover something irresistible, something visually extraordinary and emotionally moving through this process. In the meantime we will continue gradually to dismantle barriers and see where that takes us.