When this magazine’s annual issue dedicated to folk and self-taught art rolls around, I am reminded of how much I enjoy the field—not just for its utterly unexpected treasures like a James Castle scene done in soot and the artist’s saliva, but equally for those more familiar works that unite beauty to utility the way an eighteenth-century whitework quilt can. I’m not suggesting that this kind of folk art constitutes some kind of comfort zone; I am simply drawn to works that run against the art world’s tacit notion that utility disqualifies a work from consideration as art. Is it necessary to point out, as the philosopher Arthur Danto once puckishly did, that a fine artist can depict a beautiful paint-decorated blanket chest but be incapable of making one? I think it is.

Having said this, I must now confess to secretly harboring two embarrassing blind spots. Both are stellar examples of art joined to utility, and both are forms brought to perfection by American artisans, and yet I have long ignored both duck decoys and weathervanes while trying not to erect my ignorance into a matter of pride or, in the case of decoys, disguise it as an aversion to hunting. In 2015, when I heard that a duck decoy brought $1.1 million at auction, I thought it was time I had a course correction, so I called David Esterly (1944–2019), the brilliant master carver who replaced the Grinling Gibbons carving at Henry VIII’s Hampton Court Palace destroyed by fire. “I don’t get it either,” David replied, adding that, like me, he’d never really given the decoy much attention. Secretly, I felt confirmed.

It was not until I confessed my decoy prejudice to my friend the English folk art dealer Robert Young that my head was turned around. Robert was not surprised that David Esterly hadn’t seen what makes a working decoy (as opposed to those made for display) a masterful work. Robert is not a decoy specialist he says, but he has a keen eye and a passionate appreciation for the working ducks. As I trotted along after him at the Winter Show one evening he tossed back some pungent observations, which he later repeated while cautioning me that there was a lot more to know. “The great ones,” he said, referring to working duck decoys made to deceive their live brethren, “weren’t made for our eye. You feel the life in them, they capture the spirit of the bird, and that has nothing to do with verisimilitude. You can feel it.”

He had more to say but I wanted to experience that spirit for myself so I set off knowing it was not to be found in books or in Decoy Magazine (a bi-monthly publication). Jon Deeter of Guyette and Deeter, dealers in decoys among other things, confirmed Robert Young’s sense that a perfect likeness is not at all what makes a perfect decoy. He gave me a very brief history of the field and urged me to value what my eye was drawn to. Eventually I did just that when I spotted the photo of an eider decoy with a mussel in its beak by Gus Wilson, a Maine lighthouse keeper and a carver known to all who know the field. One look at this smug old duck and I was certain that if I made a sudden move he’d be off, his treasure tucked tightly in his bill. I will leave the finer points of connoisseurship, of paint and finish and balance to the experts, happy enough with my first baby step toward the animating spirit that delights so many, and wishing David Esterly were still here to share my discovery. I’m sure he, too, would see the light.

When it comes to weathervanes you don’t need one to know which way the wind blows, but it helps to have a friend like Patrick Bell of Olde Hope Antiques willing to waste a beautiful spring morning tutoring a dunce at his Manhattan gallery. Was I suspicious that most of the great vanes were factory made and thus perhaps not exactly folk art? I was, but Pat, ready for that, explained the amount of handwork and the several steps of production that went into the making of vintage weathervanes. From there we went on to examine a few examples in the gallery, and here I can only characterize his attention to surface, wear, movement, and rarity as meticulous. Can passion be meticulous? Oh, yes.

As we paged through Robert Shaw’s American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds, I began to see that there was a great deal of valuable social history to be gathered from the vanes for an enterprising scholar willing to dig it out. I also noted that the many impressive weathervanes featuring Native Americans that are now more or less out of favor also await an important study, one that can join Native American scholars, tribal elders, and folk art specialists to bring some historical grounding and sanity to the matter. Already happy that I’d come here, I was now much more so.

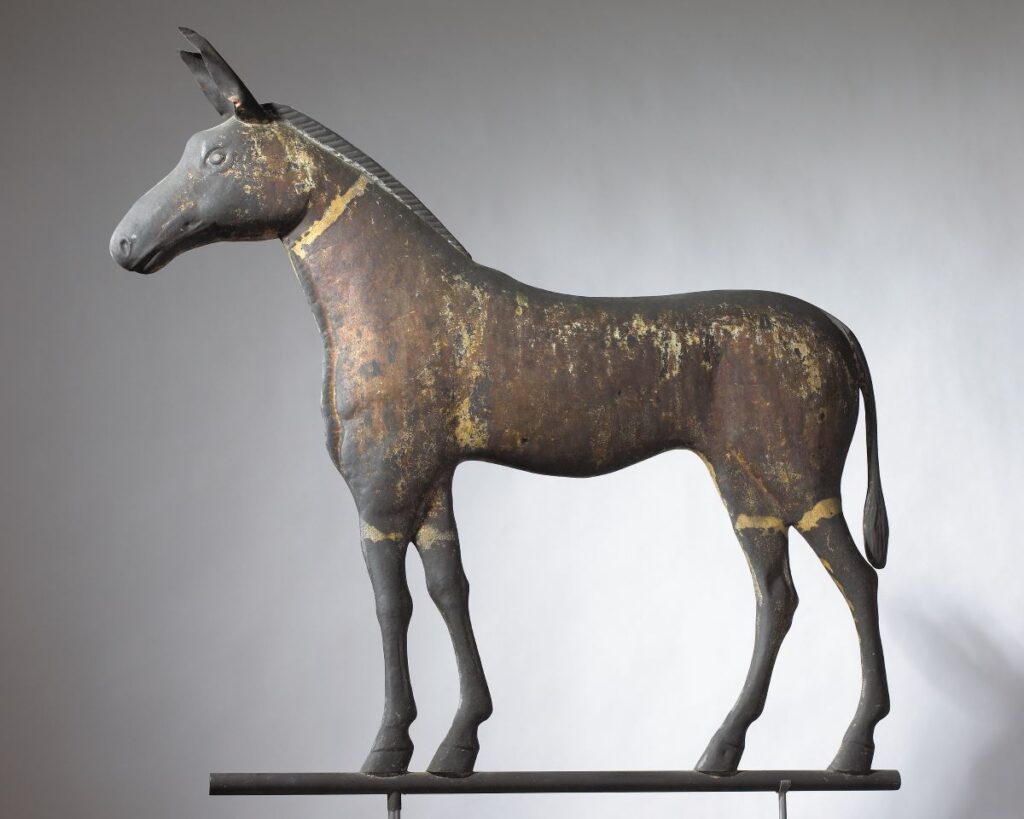

Did I learn to look at the vanes? To some extent, yes, but did I lust after one of my own? Not really, and I was content to leave it at that until I turned one more page of the book and spied a mule weathervane that really delighted me for putting that beast of burden atop a rod instead of at the mercy of one. My delight sparked a conversation about mules, about Missouri—where both Pat and I have family roots—and, most amusingly of all, occasioned Pat’s description of the animal husbandry that goes into the making of an actual mule!

Perhaps you have noticed that these two anecdotes come from a person who finds the world of tangible objects almost as alluring as the conversations they can inspire—those moments of repose in a volatile, virtual world. That’s what the field of folk art, and of antiques in general, has given me. You can’t digitize that.