After looking through the art world’s fall previews recently, I decided that instead of bracing myself for the noise that will inevitably surround a celebratory retrospective of the deeply frivolous artist Judy Chicago (whom I think belongs more to the history of publicity than to the history of art), I ought to get a healthier dose of feminism and visited the New-York Historical Society’s exhibition Women’s Work.

If you didn’t know better, the Joyce B. Cowin Women’s History Gallery on the fourth floor of the NYHS might conjure images of aggrieved and overlooked females dutifully arrayed with hectoring wall labels aligned to some theme or other—in short, a reliable downer.

As it happens, the gallery is nothing like that. In its five-or-so-year history, it and the NYHS have been lively, amusing, and revelatory, doing much to dispel the reputation of the women’s movement as perennially humorless and monochromatic. Right now, and until July 7, 2024, Women’s Work, drawn from objects, art, and photographs in the museum’s enormous collections, manages to be enticing and lighthearted while also maintaining a fierce undertow—just as it should.

Let’s begin with the jaunty brochure that describes itself as a family guide. Meant, I suppose, for those somehow unaware of our historic struggle, it encourages a range of activities from lining up the ten arduous steps it took to do a load of wash by hand to locating a photo of Marsha P. Johnson, the trans woman who ignited the 1969 Stonewall Uprisings and worked tirelessly to prevent housing discrimination. Marsha Johnson had a motto, “pay it no mind,” and visitors are given a space on the brochure to write down a motto of their own. “Keep going,” I scribbled in the spot provided.

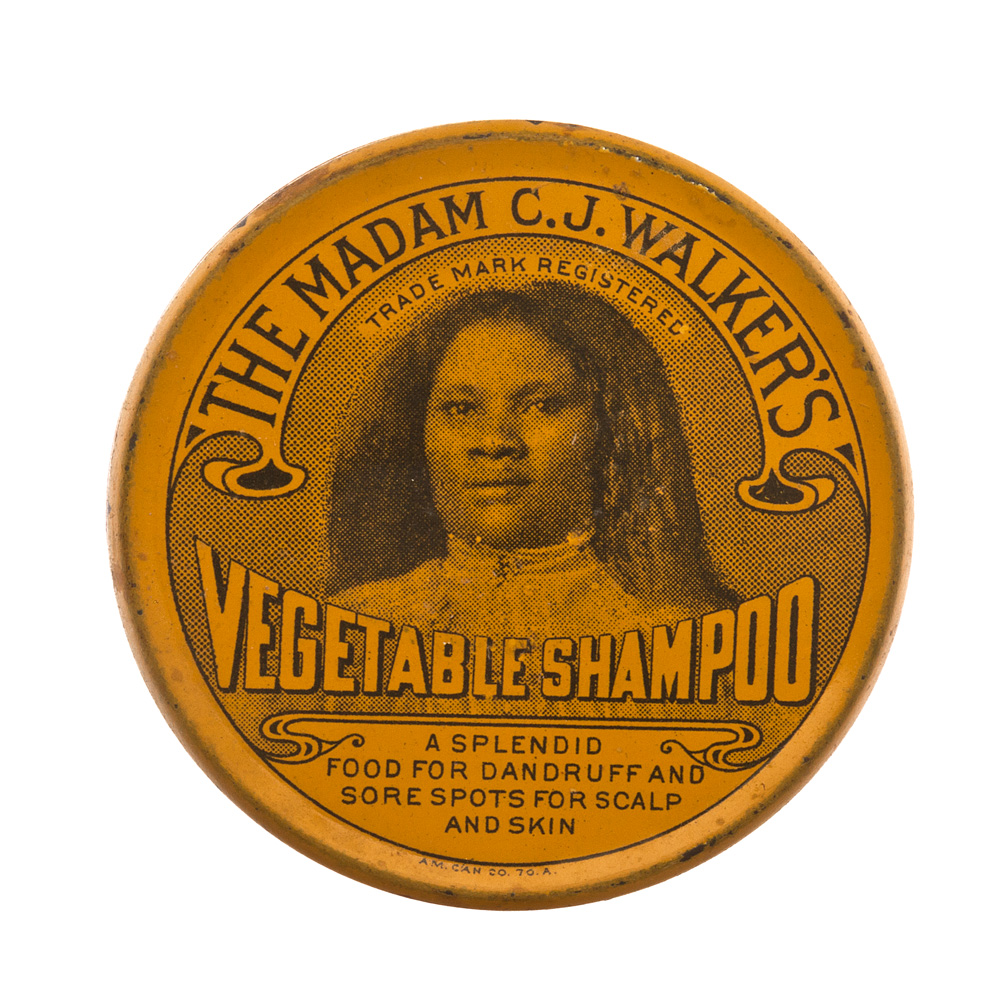

Fun stuff, but what delighted me was the exhibition’s vast miscellany of the known, the unknown, and the forgotten in the world of work: the sugar nippers used by enslaved women in New York’s sugar refineries; a bit of Billie Holiday singing her most beautiful ballad, “I’ll Be Seeing You,” recorded before the FBI had her cabaret license revoked and put her out of work altogether; a bust of the actress Charlotte Cushman (1816–1876), once famous for excelling in male roles like Hamlet and Romeo; emblems of the garment workers union; photos of sex workers and street vendors; an Autocrat typewriter ribbon from the 1920s; a tip tray from 1900 to 1920; and so forth. There are even paintings and antiques here, among them a Duncan Phyfe lady’s worktable of about 1820!

A mess? No, a keen exercise showing that almost anywhere you place your finger on the vast map of New York’s material history, you will find a moment of female significance. What you won’t find here is a hierarchy of the working world; those street vendors and garment workers appear with no less emphasis or fanfare than Joan Ganz Cooney, originator of Sesame Street, or the inevitable Eleanor Roosevelt.

You will also find wall labels with enough social and economic history to explain the gendered history of tipping, for instance, or, in the case of a tin of condoms, the long (and ongoing) struggle for reproductive rights waged by Margaret Sanger among others—all delivered succinctly in matter-of-fact prose.

There are also few moments of muted outrage: a photograph of Mary Edwards Walker (1832–1919), the first female surgeon in the US Army, who served in the Civil War, was captured by Confederate forces, returned in a prisoner exchange, and awarded the Medal of Honor, the only woman ever to receive it. The medal was revoked in 1916 . . . but eventually restored in 1977. Who knew? And that is part of the point, as a largely forgotten history joins a more familiar one.

Even the title of the exhibition is somewhat sly, hinting as it does at the traditional consignment of lesser occupations as “women’s work,” while simultaneously undermining and elevating that phrase.

The interior architecture here is one of the show’s pleasures— open, inviting, and anything but somber. You enter with your own history in tow and if it is a burdensome one, the load is somehow lightened. Perhaps, like me, you are old enough to remember the 1950s, when women’s magazines published fiction in which the working world was often depicted as an arena of punishment for women, a discouraging message for a young kid. As I walked along, I recalled the hot Chicago summer in the 1960s when I was punished by being sent to work in the girdle department of Saks Fifth Avenue. Instead of being miserable, as I think my parents had hoped, I was inspired by the camaraderie of the older women I worked with (known then as salesgirls); they taught me a great deal about what working women with challenging lives endure and how solidarity lightens the load. There’s more than a bit of that spirit in the Joyce Cowin gallery at the NYHS, and I was as grateful for it recently as I had been that summer so long ago.