It’s not often these days that I find myself as surprised by joy as I was on the first of several trips to the Morgan Library and Museum this spring. During our months of semi-confinement my paths to pleasure have been too well-worn for the euphoric moments I treasure, the ones that catch me off guard. I went to the Morgan expecting to be moved by the new Woody Guthrie exhibition and I was; I expected to be awed by their Hans Holbein portraits, as anyone with a heartbeat would be; and I knew I’d be gratified to find a prominent gallery, the first one you see when you enter the museum, devoted to a favorite poet, Gwendolyn Brooks. But the joy, as I’ve said, surprised me. It came in waves as I considered how seamlessly these disparate shows complemented one another without distinctions of hierarchy, geography, time, or race. And without any institutional pandering or self-congratulatory “look at us!”

All of this at the Morgan? Yes, the Morgan. They’ve been doing it for years. Well, at least since 2006 when Renzo Piano’s international style expansion opened, joining the museum’s three buildings, and moving the entrance from the sedate side street to busy Madison Avenue. Back then there were those who considered the new Morgan an affront to all three structures, especially to Charles McKim’s landmarked marble masterpiece of 1902–1906. I may have been among them, but not for long. Is the Morgan a seamless marriage of the old and twenty-first-century sleek? By no means, but it is one of those improbable marriages that somehow works. This summer the garden on Thirty-Sixth Street will reopen after a restoration. Will its traditional plantings fit nicely with those in the Gilbert Court, Piano’s glass and steel atrium? I’m not sure it matters; there can be any number of rough juxtapositions in the Morgan, from Beethoven manuscripts to Bob Dylan’s lyrics. The museum is small enough to let any combination of them—from medieval incunabula to Babar—bear unusual fruit.

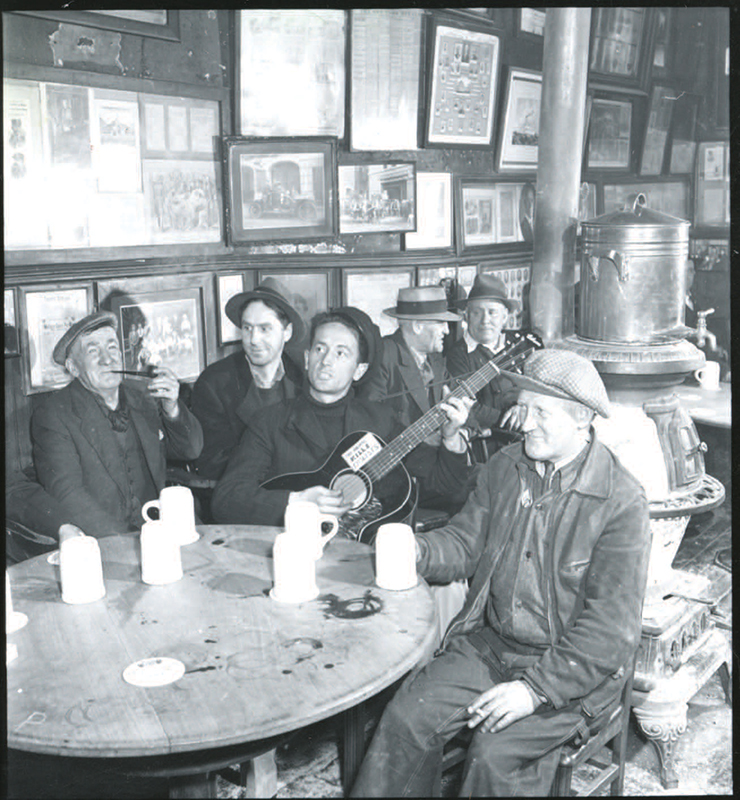

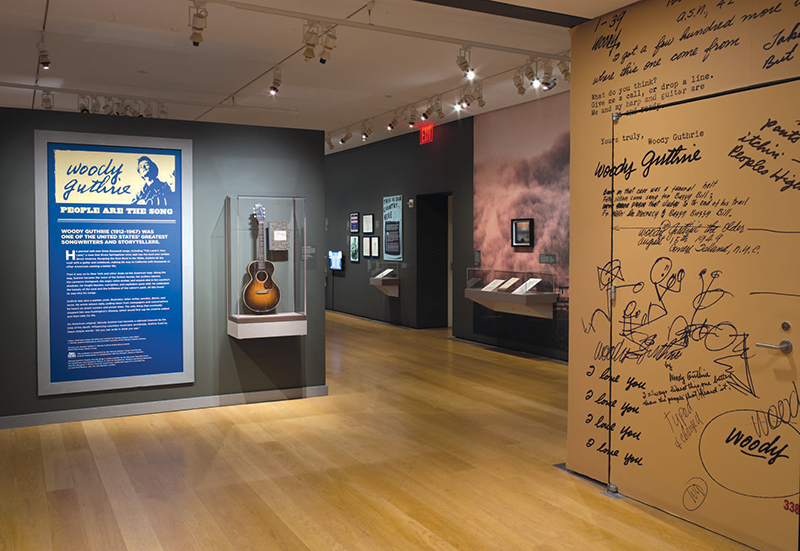

Let’s begin by dismissing the cheap irony that the songs, drawings, photographs, and musical offspring of that antic lefty Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (1912–1967) are bringing crowds to the home of uber financier J. P. Morgan. Woody Guthrie: People are the Song (on view to May 22) makes nothing of this, and you won’t either as you enter the gallery, engulfed by the tidal wave of Guthrie’s astonishing creativity—and all that it has inspired. In a beautiful combination of then and now, the videos, playlist, and interactive screens invigorate the wall labels and flat art by a guy who wanted to be heard, touched, and seen. He was a kid all his life and that comes across. From his Oklahoma childhood, where fire consumed his beloved sister and the flames of his mother’s Huntington’s disease torched what was left of family life, to his years on the road, ending in Coney Island, the death of an adored daughter, and his own Huntington’s diagnosis, Woody’s story, improbably enough, is one of joy triumphant. The Depression, the Dust Bowl, a World War and all that death and disease were transformed in the songs and drawings. That is certainly a big part of why he lives on . . . as you will see.

Everything here has been thought of, right down to a wall label from the Cherokee Nation that casts a cold eye on the lyrics of “This Land is Your Land,” something Woody would undoubtedly have approved. The show’s curator, Philip Palmer worked closely with Nora Guthrie, Woody’s indefatigable daughter, and the Guthrie Center in Tulsa, where much of this material resides. You can take some version of the exhibition home in the form of a handsome new book of “songs and art, words and wisdom” assembled by Nora Guthrie and Robert Santelli available in the museum’s gift shop, where, if you’re lucky, Woody, will be singing “Pastures of Plenty,” or maybe “So Long It’s Been Good to Know Ya.”

But don’t leave yet. Hans Holbein: Capturing Character (on view to May 15) is only a flight of stairs away from Woody Guthrie. Holbein was an artist in far more dangerous and polarized times than ours—from the Reformation in his native Germany to his days with the court of Henry VIII—though you might not guess it from the civilized restraint with which he approached his work. I will leave exacting descriptions of his stupendous artistry to others and simply record my response to an exhibition that originated at the Getty in Los Angeles and finds a special home here in New York, where it has been reviewed widely, something unusual for an art press increasingly negligent of works from the past, especially the more recent past (as I write, the Guthrie still has not been reviewed by the Times, the Wall Street Journal, or many other publications).

Holbein’s portraits of eminent figures such as Erasmus and Thomas More are justly famous for many things. I find them remarkable for the way in which they locate the humane in humanity, but I am especially drawn to his portraits of London’s German merchants, men unaccustomed to confecting their images for public view but figures Holbein probably knew quite well. Clearly I am not alone because one of these portraits, described vaguely as a member of the Wedigh family, was chosen for the cover of the catalogue and it is a marvel. This merchant is imbued with enough character to make you want to supply your own caption: Is he about to cut your heart out, crack a joke, or kick a pigeon? We cannot judge and we are not meant to.

Holbein kept his head down during his London years, a good thing for a painter in the court of Henry VIII, but he was quietly heroic all the same. Don’t miss his Dance of Death woodcuts, in which that terrifying medieval theme acquires a new layer of menace by making figures like the plowman a recognizable person rather than a type. And look again at the great portrait of Thomas More, who famously lost his life but not his honor.

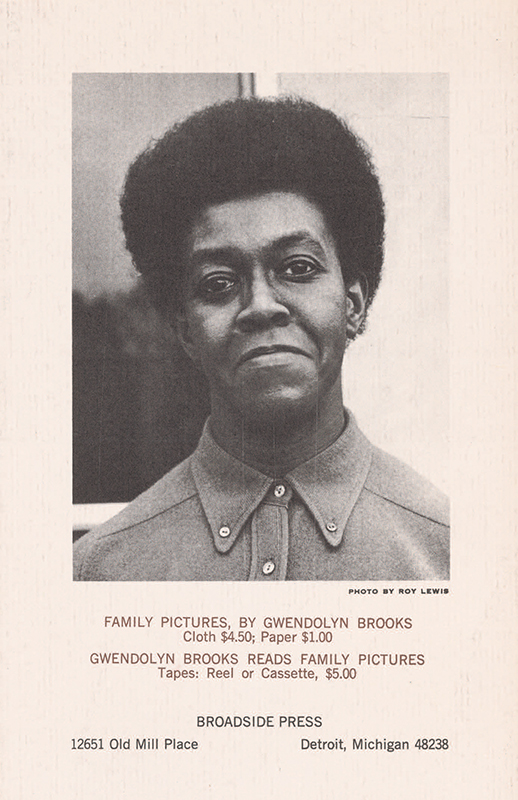

Off and on for decades now, museums have played a role as arenas for conflict resolution, for righting so far as they can some of the wrongs of history. If that were the only reason for mounting an exhibition devoted to the poet Gwendolyn Brooks (1917–2000), the first Black person to win, in 1950, a Pulitzer Prize in any category, it would not be enough. Fortunately, the Morgan’s Gwendolyn Brooks: A Poet’s Work in Community (on view to June 5) has far more in mind. Brooks was a superb poet, something that comes across in the Thaw Gallery, where broadsides, photographs, and first editions are displayed, and her poems unfurl slowly on a screen, allowing you to read them as they should be read—and to meet the poet who began in the 1930s on Chicago’s South Side as the bard of the daily sublime, of “peach cans and jelly jars.”

Gwendolyn Brooks never really left her neighborhood, but she didn’t sit still either. By the 1960s when you might have expected the tidal wave of Black power to sweep her aside, she became a mentor to the Black arts movement while also writing some of her most incandescent poems. A Brooks exhibition is not a sometime-y thing for the Morgan; they have been building a collection of her work for a while now.

Like Woody Guthrie, Gwendolyn Brooks had a fresh, improvisatory voice, one that emerged from a harsh environment—an American voice. Nicholas Caldwell, the curatorial fellow responsible for the Brooks exhibition, says visitor responses to it have been at times quite emotional, something also true of the Guthrie as I can attest. All three shows have reached beyond their expected audiences to find people “by every channel possible,” according to Jessica Ludwig, the Morgan’s deputy director. Family programming, concerts, school trips, Zoom talks can do this work, though I’m not sure any of them replace the solo encounter.

So, visit. Perhaps you’ll go home and read a poem, watch A Man for All Seasons, or listen, as I did, to Mermaid Avenue, Woody’s lyrics set to the music of Billy Bragg and Wilco (another Nora Guthrie inspiration). Whatever you do, I’m pretty sure you’ll have left the museum happier than when you arrived.