The little Gothic revival building on Park Avenue South lived a much different past. You can imagine the atmosphere of serene spirituality that prevailed when it was part of the Calvary Church complex. The air in the compact interior space—where the ceiling is supported by an elaborate and attractive system of wooden trusses and arched corbels—once rang with the sound of hymns, the lilting poetry of psalms, and talk of catechism and the liturgy. But in the here and now, rather than the strains of “All Things Bright and Beautiful,” you hear the rattle of cocktail shakers, low-key electronic house music, and the laughter and murmured gossip of—as promotional material puts it—“bon vivants, provocateurs, and culturati.”

Welcome to the Chapel Bar, a converted church annex built in 1867 that is now a members-only lounge for patrons of the New York outpost of Fotografiska, the Stockholm-based photography museum and exhibition space. For annual dues of $2,000 (plus a $500 initiation fee) top-tier Fotografiska members have unlimited access to the Chapel Bar, where they can sit and sip in candlelit alcoves, at once modern and medieval in feel, and discuss the current state of art and culture (and who’s sleeping with whom).

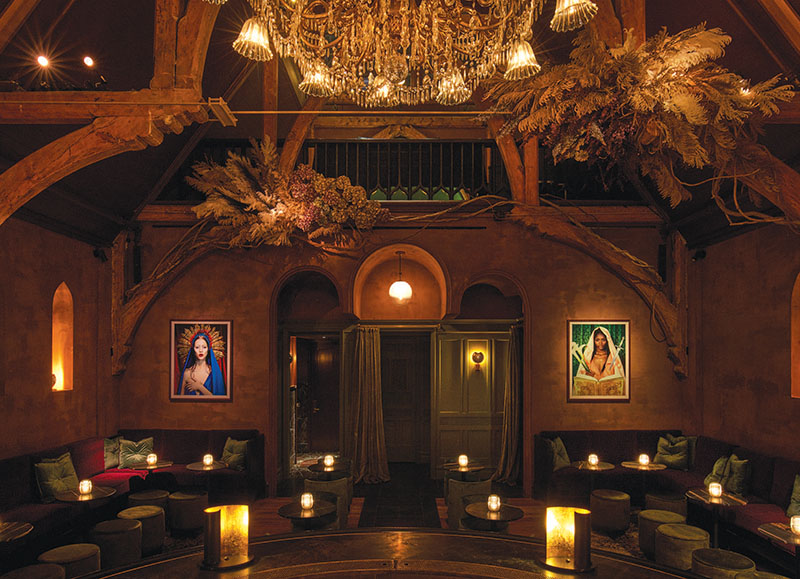

On a recent Saturday night, I entered the chic spot— passing the bouncer, the host, and the coat-check, and ducking through purple velvet drapes into the main bar—and found myself in a room that felt almost like a set from the film Eyes Wide Shut, director Stanley Kubrick’s infamous 1999 tale of the rich and strange. Plush finishes, intimate seating, and touches such as photographer Miles Aldridge’s contemporary takes on saintly portraits all come thanks to the fashionable New York interior design firm Roman and Williams. At the back of the nine hundredsquare- foot space, adorned with handsome, oversize bouquets, three bartenders in matching gold-buttoned smocks manned the narrow U-shaped bar, handing out heavy glasses filled with house specialty cocktails, all named by Roman numerals. (Fotorgrafiska marketing staff are fond of religious plays on words in descriptions of the Chapel Bar, calling it things like a “sanctuary for culture” and “a place for communion.”) I tried the VI—a blend of mezcal, agave nectar, and other trimmings. Not bad.

Such cosmopolitan and sybaritic goings-on are scarcely what the building’s architect could have envisioned for the little place. It was designed by James Renwick Jr.—who would go on to plan out St. Patrick’s Cathedral, completed in 1879—as part of his commission for Calvary Church, a venerable Episcopalian congregation founded in 1832. The annex was originally intended to be a theater, but soon was converted into a Sunday school. Built of brownstone, it is topped by a square, hipped cupola, and a roof clad in multishaped and -colored slate tiles. Because the diminutive structure stands in the shadow of two larger buildings, Renwick outfitted the cupola with forty-two clerestory windows to bring in light. The hammer trusses and braces inside that support the roof eliminated the need for exterior buttresses. Sweet and picturesque, the building has become known as the “Renwick Gem.”

The adjacent Fotografiska museum occupies another historic building: the landmark Church Missions House, built in 1894, to the designs of Robert W. Gibson and Edward J. N. Stent, to accommodate the offices of the Episcopal Church’s worldwide missionary societies. All of Fotografiska’s locations—New York joins another operating outpost in Tallinn, Estonia; others will soon open in Berlin, Shanghai, and Miami—employ historic, or at least older, buildings. The Stockholm flagship occupies a disused art nouveau customhouse; the Berlin Fotografiska will be situated in a former department store built in about 1908. Harnessing the aura of the past is only one aspect of Fotografiska’s vision for a new type of cultural institution—one where art appreciation is joined to high-end and exclusive hospitality. Last year, the Swedish museum merged with NeueHouse, a New York and Los Angeles firm that offers combined work, meeting, and socializing facilities to creative types such as designers, artists, film producers, and those presumably innovative luminaries known as “thought leaders.” To judge by the stylish young crowds gathered in Fotografiska’s New York galleries and at the Chapel Bar, their ambitious concept for the future of the museum seems to have more than a prayer for success.