A sculptor who worked in wood, Bernard Langlais is a household name only among connoisseurs of avant-garde art who have a connection to Maine. In a nutshell, Langlais’s art is plunk in the center of the crossroads of abstract expressionism and folk art, of the rough-hewn sensibility of Mainers Winslow Homer and John Marin, and the whimsy of Claes Oldenburg and Red Grooms. He was a Maine original.

Langlais was born in Old Town in central Maine, one of ten children of a Québécois carpenter. He’s known mostly among collectors for small, painted sculptures of birds and animals, precisely chiseled but looking craggy enough to seem wild and lifelike. As a young man, he studied at the Corcoran School of Art and the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and won a Fulbright Scholarship to go to Oslo to absorb the work of Edvard Munch.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s in New York, Langlais made unusual abstract expressionist wall sculptures using bits of found wood. Different textures, finishes, and sizes make for an aesthetic puzzle in look and theory. They’re modern, to be sure, but aren’t iconic, flamboyant, glitzy, or urbane. Rather, they’re deliberate and quiet. The wood’s worn, each piece with a history of human use and touch. They’re gestural insofar as looking handmade but it’s the handwork not of paint splashed on a canvas but of the furniture, baskets, and vernacular architecture of an older era.

In the 1960s Langlais became a very hot artist, very quickly. He was represented by the top-flight gallerists Leo Castelli and Allan Stone. The Whitney showed his work. But in 1965, disgusted by the pressures of gallery representation, he went back to Maine and bought a ninety-acre farm in Cushing. He felt pushed by Castelli to make the same art over and over rather than follow his vision, which more and more led him toward representational rather than abstract art, and toward work that seems on the edge of folk traditions.

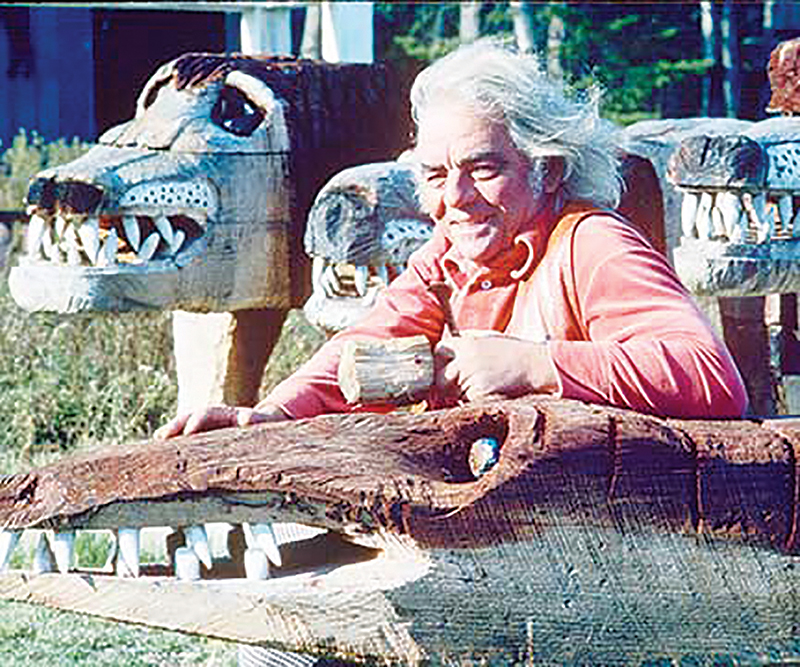

For the rest of his life, he focused on two- and three-dimensional sculptures of birds and animals, usually life-size, and more than sixty big, outdoor, totemic sculptures that he installed on his property. His work is playful, eccentric, and delightful. He liked the terms “simple and childlike,” more a description of appearance than process since Langlais was an exacting artist. That said, his big work never looks entirely finished, and it never was. Langlais fiddled with his art all the time.

He ignored the art movements of the era. Pop art’s irony and critique of consumer culture are nowhere to be found in his work; nor are the tenets of minimalism, conceptual art, feminist art, nor those of the artists known as the “Pictures Generation.”

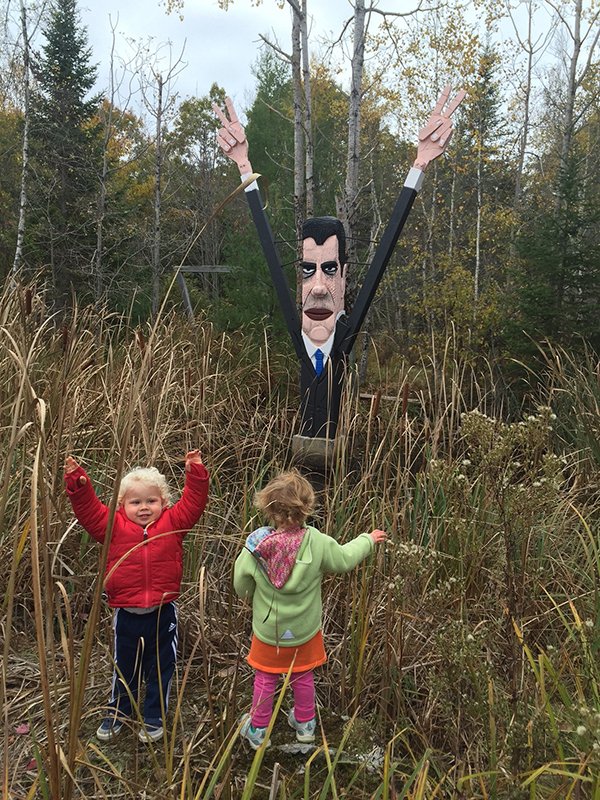

Langlais sold his small sculptures through a Portland, Maine, dealer. A seventy-foot-tall sculpture of a Native American in the center of Skowhegan, southwest of Bangor, gave him a public profile. In 1974 he received national attention via a large outdoor sculpture of Richard Nixon, placed in a swampy bit of land on his property, arms and hands giving the V-for-victory sign that marked Nixon’s exit from Washington in disgrace.

After Langlais died, his wife, Helen, continued to live on their farm in Cushing. She kept his studio and rudimentary sculpture park intact, preserving both by leaving them alone. When she died in 2010, she bequeathed the farm, studio, and art to Colby College.

This had to have been seen by some Colby administrators as more of a curse than a blessing. A ninety-acre, marginally successful farm some fifty miles from the Colby campus, an old house, sixty outdoor sculptures of elephants, polar bears, beavers, and Nixon, many rotting away, two thousand drawings and prints filed in baskets and chests, nine hundred other works of art, and a massive, well-equipped studio unused for more than thirty years, and very little cash—these are not normally seen by college fundraisers as manna from heaven. Yet the very good Colby College Museum of Art took charge.

The museum enlisted the Kohler Foundation in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, for help. It was a brilliant move and an out-of-the-blue one. The Kohler is an art focused foundation whose convention is to be unconventional (see our piece on its latest developments on pages 44–50). It likes cutting edge, under-the-radar artists, usually alive. Though Langlais was long dead, his work seems current in our time, which craves authenticity and celebrates outsiders. Hierarchies putting painting above all else and the privileging of New York artists are notions that are now getting chucked out the door.

Kohler took over the conservation of the Langlais property’s outdoor sculptures. Conservation is one of its specialties, and the foundation’s experts did a fantastic job. Today, they’re in good condition. They’re hewn, chiseled, and planed wood, most painted. Fifty Maine winters have weathered the sculptures, but they’re stable, whimsical, and compelling, all accessible on good trails, and much loved by visitors.

The Langlais preservation project has yet another partner. The Georges River Land Trust owns more than four thousand acres of open space in mid-coast Maine, maintains a network of hiking trails, and keeps the land pristine. It’s a big player in Maine land-use circles. The trust took over ownership of the Langlais farm and sculpture preserve, giving the site an established, local parent to protect and promote it.

It’s amazing that a loner like Langlais, a mutineer against the New York art market, should have stimulated a sophisticated, unusual collaboration among three blue chip organizations.

The Kohler Foundation is also, slowly but surely, giving Langlais a national presence. Colby College gave the foundation the bulk of the art it inherited. Kohler is giving it to museums across the country. Scholars and art lovers will be able to know Langlais firsthand as an artist who crossed borders. Kohler did something else that’s remarkable: creating a Langlais Art Trail throughout the state, the foundation distributed work by Langlais to public libraries, town halls, schools, and community centers all over Maine. Langlais was a Maine artist, after all—a brilliant, eccentric rustic finally getting his due.