The current vogue among young city dwellers for anachronisms such as waxed handlebar mustaches; the popularity of locally sourced produce, specialty butcher shops, and artisanal cocktails; the success of handicraft-focused ventures like Etsy—all these trends seem to reflect a nostalgia for the perceived simplicity of bygone eras, and a yearning to temper the frenetic pace of our technology-driven world. This contemporary impulse had an analogue in the country’s fascination with its preindustrial roots during the 1920s and ’30s—the period known as the Machine Age.

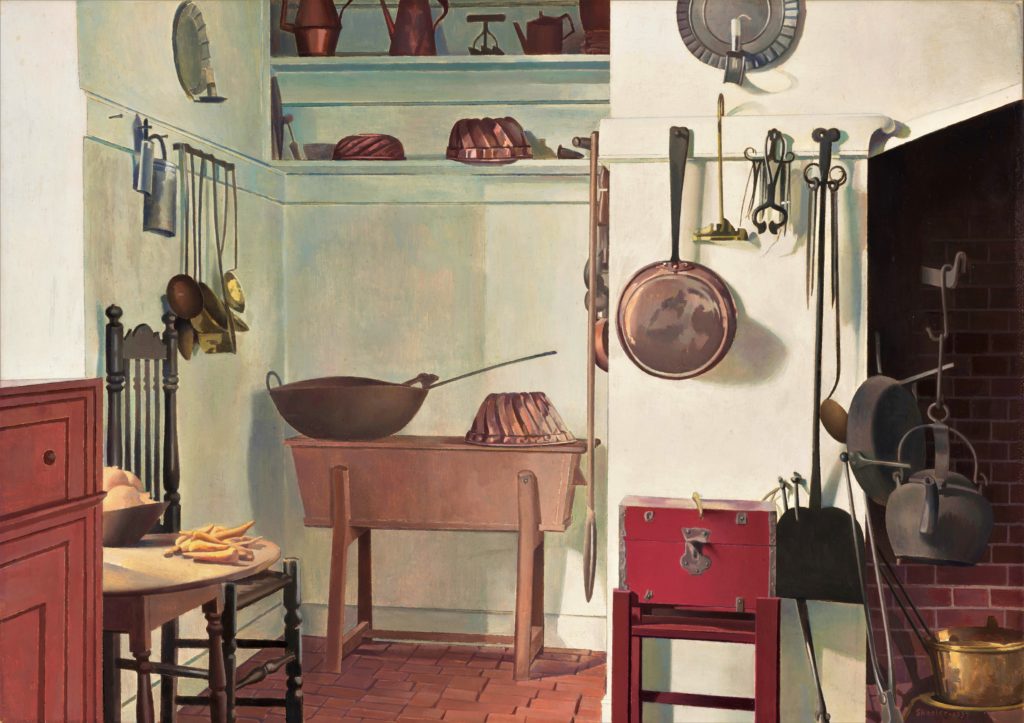

Fig. 1. Kitchen, Williamsburg by Charles Sheeler (1883–1965), 1937. Signed and dated “Sheeler – 1937” at lower right. Oil on hardboard, 10 by 14 inches. The scene depicted is an interior in the Governor’s Palace at Colonial Williamsburg. The painting is in the de Young Museum, where it is installed in a gallery of colonial era objects to emphasize the enduring fascination historical objects have had (and continue to have) for modern viewers, and how objects accumulate meaning over time. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd; photograph by Randy Dodson.

Fig. 2. Sheeler standing next to a window in a photograph by Peter A. Juley & Son (active 1896–1975), c. 1910. Archives of American Art, Forbes Watson Papers.

Even as skyscrapers rose and the automobile became a staple of American life, the era saw a growing zest among collectors for early American vernacular art, architecture, and decorative art objects. Folk paintings and Shaker furniture were particularly prized, and their simple forms were often related to the utilitarian and efficient designs of the twentieth century.1 The widespread interest in America’s craft heritage was reflected—and shaped—by museum initiatives and historic preservation projects that ranged from the opening of the American Wing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1924 to the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia, which began in 1926. Among the ardent enthusiasts for the simple and pastoral—as demonstrated by many artworks in Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art, an exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco—were, perhaps surprisingly, artists associated with the precisionist style, many of whom made rural scenes a staple of their imagery, alongside urban and industrial environments.

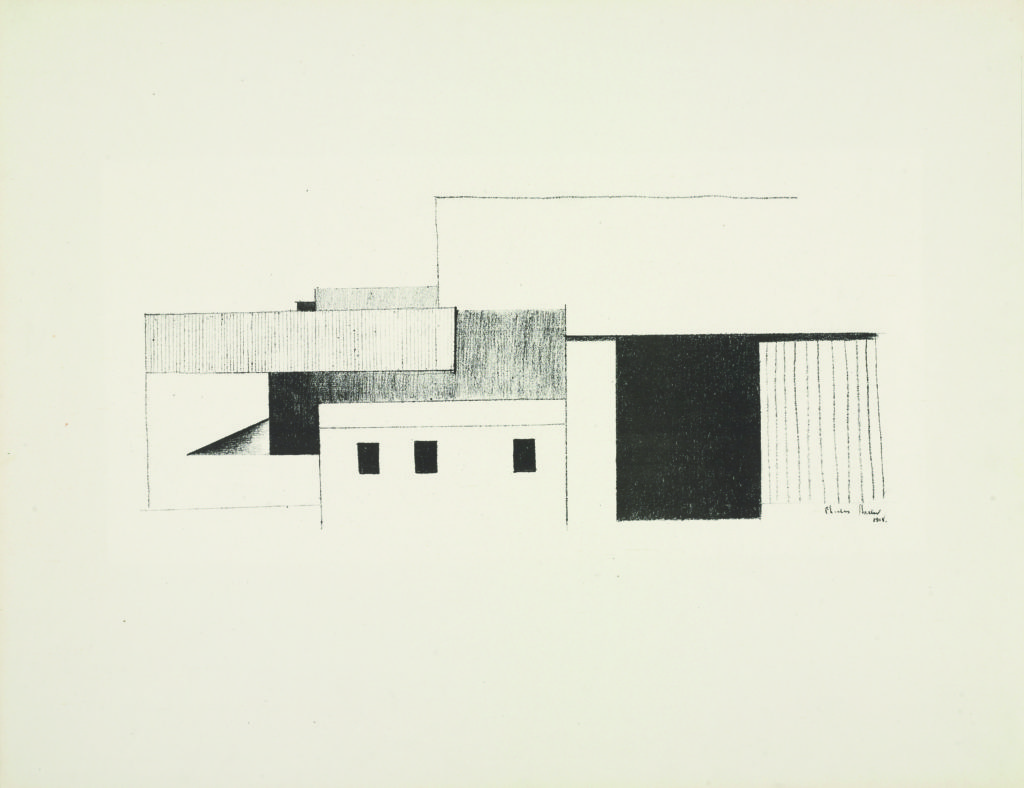

Fig. 3. Barn Abstraction by Sheeler, 1918. Signed and dated “Charles Sheeler/1918.” at lower right. Lithograph, 19 3/4 by 25 5/8 inches. Museum of Modern Art, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Fund, © Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY; image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

An avid collector of Shaker furniture, precisionist Charles Sheeler (Fig. 2) was a firm believer in the continuity between historical vernacular and modern design, stating of his collection of nineteenth-century American artifacts, “I don’t like these things because they are old, but in spite of it. I’d like them still better if they were made yesterday because then they would afford proof that the same kind of creative power is continuing.”2

Fig. 4. Bucks County Barn by Sheeler, 1932. Signed and dated “Sheeler-1932” at lower right. Oil on board, 23 7/8 by 29 7/8 inches. Museum of Modern Art, gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, © Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY; image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Based on a photograph from a series commissioned in 1935 by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller to document Colonial Williamsburg, Sheeler’s Kitchen, Williamsburg (Fig. 1) encapsulates the telescopic elision of past and present characteristic of the period. The painting depicts a kitchen interior in the Governor’s Palace, a building that burned to the ground in 1781 and was completely reconstructed in the early 1930s. Sheeler represented in meticulous detail the utilitarian objects with which it was furnished—antiques collected in the 1920s and 1930s to convey a twentieth-century fantasy of colonial life.

Fig. 5. Lake George Barns by Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), 1926. Oil on canvas, 21 1/4 by 32 inches. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota, gift of the T. B. Walker Foundation, © 2017 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

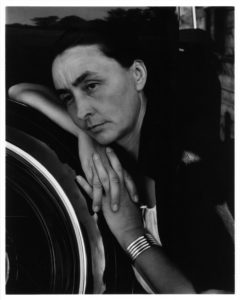

Fig. 6. Georgia O’Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), 1933. Gelatin silver print, 9 3/8 by 7 3/8 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Georgia O’Keeffe, through the generosity of the Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation and Jennifer and Joseph Duke.

Barns became a frequent subject in the work of many precisionist artists, among them George Ault, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Sheeler, who depicted these agricultural buildings with the same linear contours and architectonic compositions they had used to represent urban and industrial scenes.3 Using a subdued palette of mostly cool gray, green, violet, and blue tones, in Lake George Barns (1926) (Fig. 5), O’Keeffe emphasized the simple, austere geometries of a group of barns on Alfred Stieglitz’s thirty-six-acre family estate, which was located north of the Village of Lake George in upstate New York, and where she spent part of each year from 1918 to 1934. O’Keeffe made a total of fourteen abstracted paintings depicting barns on the Stieglitz property in varying weather conditions. Having grown up on a farm in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, she felt an affinity with these rural structures, stating, “The barn is a very healthy part of me. . . . it is my childhood.”4

Fig. 8. George and Louise Ault in Woodstock, New York, in a photograph of c. 1940. Archives of American Art, George Ault papers, 1892–1980.

Sheeler was particularly enamored of the “functional” shapes of the “early barns of Bucks County,” in Pennsylvania, stating, “the strong relationship between the parts produces one’s final satisfaction. This may well be of importance to the artist who considers the working of the parts toward consummation of the whole as of primary importance in a picture.”5 While many of Sheeler’s renderings of barns are realistic—such as Bucks County Barn (1932) (Fig. 4)—one of his earliest treatments of the subject, Barn Abstraction (1918) (Fig. 3), is much more radically pared down. In this startlingly spare, simplified composition, Sheeler delineated the structural bones of a barn and its outbuildings in Bucks County using stark tonal contrasts and a series of overlapping, rectilinear planes punctuated with areas of surface texture and pattern that are reminiscent of cubist collage.6 Voids such as windows and doors are suggested by black rectangles, recalling the suprematism of Kazimir Malevich.

Andrew Hemingway argues that the paintings of barns produced by George Ault (see Fig. 8) in the last decade of his life “introduced ideas of loss and mourning for a traditional mode of rustic life.”7 Plagued by a troubled family history encompassing financial misfortunes, mental illness, and a tragic series of suicides, Ault was predisposed to a bleak outlook—which was compounded by his horror at world events, particularly the rise of fascism during the 1930s and 1940s—and his depressive and reclusive nature may have influenced the melancholy quality of his scenes of both urban and rural America, which are marked by their uncanny stillness. In his enigmatic, hauntingly beautiful January Full Moon (1941) (Fig. 7), Ault depicted a solitary, snow-covered barn dramatically silhouetted against a night sky in Woodstock, New York, where he lived from 1937 until his death in 1948.

Fig. 7. January Full Moon by George Copeland Ault (1891–1948), 1941. Signed and dated “G.C.Ault’41.” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 20 1/4 by 26 3/8 inches. Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, purchase William Rockhill Nelson Trust (by exchange); photograph by Jamison Miller; image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The significant number of rural subjects in precisionist art is surprising, given how synonymous the style has become with the industrial landscape. Just as the precisionists attempted to forge an original American art independent of European traditions by embracing as subjects the nation’s modern skyscrapers, smokestacks, factories, and bridges, so too did they reflect and celebrate America’s cultural identity by drawing inspiration from its agrarian roots and design traditions—striving to capture in all its many guises what O’Keeffe termed the “Great American Thing.”8 Works with seemingly patriotic titles—such as Sheeler’s Americana and O’Keeffe’s Cow’s Skull: Red, White, and Blue (both 1931)—were made in the early stages of the Great Depression, perhaps signaling a desire to assert national pride in the face of economic hardship.

Fig. 9. Classic Landscape by Sheeler, 1931. Signed and dated “Sheeler–1931.” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 25 by 32 1/4 inches. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Barney A. Ebsworth; image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Reflected in precisionist artists’ frequent representations of the nation’s rural landscapes, regional architecture, and traditional handicrafts, Machine Age Americans’ desire to resurrect the country’s colonial roots and craft heritage—and connect them to their own cultural moment—stemmed in large part from a celebratory, nationalist impulse. Yet this penchant may also have served as a bulwark against the newness and strangeness of the present, familiarizing and historicizing aspects of modern American life that were in reality radically—and for many, troublingly—dissimilar from the past.

This essay is excerpted and adapted from “Engineers of an American Art: Precisionism in the Machine Age,” in the catalogue to the exhibition Cult of the Machine: Precisionism and American Art, on view at the de Young Museum in San Francisco from March 24 to August 12.

1 For extended discussions of this subject, see Wanda M. Corn, The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (University of California Press, Berkeley, 1999), pp. 293–337; and Kristina Wilson, “Ambivalence, Irony, and Americana: Charles Sheeler’s ‘American Interiors.’” Winterthur Portfolio: A Journal of American Material Culture, vol. 45, no. 4 (Winter 2011), pp. 249–276. 2 Quoted in Constance Rourke, Charles Sheeler: Artist in the American Tradition (Harcourt, Brace and Co., New York, 1938), p. 136. Sheeler also wrote, “The forms of the Pennsylvania barn are of interest because of the evidence that they served the necessity of the people who built them. Forms created by industry to meet its needs also carry conviction and claim the attraction of the artist for the same reasons.” Sheeler, manuscript autobiography, Charles Sheeler Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, reel NSH1, frame 101. 3 Sheeler stated, “Anything that works efficiently is beautiful. Barns and machinery are thus beautiful.” Charles Sheeler Papers, reel NSH1, frame 324. 4 Georgia O’Keeffe to Mitchell Kennerley, January 20, 1929, Mitchell Kennerley Papers, New York Public Library; quoted in Roxana Robinson, Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life (Harper & Row, New York, 1989), p. 19. 5 Quoted in Rourke, Charles Sheeler: Artist in the American Tradition, p. 99. 6 Critic Henry McBride compared the drawing for Barn Abstraction to work by Pablo Picasso. See McBride, New York Sun, February 22, 1919 (Henry McBride Papers, Archives of American Art, reel NMcB2, frame 304). Sheeler stated, “The artist may learn much from the contrasting surfaces employed in this architecture—wood, stone, plaster. Contrasting surfaces may contribute much to a picture, not merely to create interesting variations but for the actual design. A given texture, as of rough stone, may hold the attention by its rich complications and so give emphasis or depth which could not otherwise exist. A smooth texture may bring about a quickened tempo which may be essential to the whole.” Quoted in Rourke, Charles Sheeler: Artist in the American Tradition, p. 98. 7 Andrew Hemingway, The Mysticism of Money: Precisionist Painting and Machine Age America (Periscope, Pittsburgh, 2013), p. 201. 8 O’Keeffe wrote: “When I arrived at Lake George I painted a horse’s skull—then another horse’s skull and then another horse’s skull. In my Amarillo days cows had been so much a part of that country I couldn’t think of it without them. As I was working I thought of the city men I had been seeing in the East. They talked so often of writing the Great American Novel—the Great American Play—The Great American Poetry. I am not sure that they aspired to the Great American Painting. Cézanne was so much in the air that I think the Great American Painting didn’t even seem a possible dream. . . . I was quite excited over our country and I knew that at that time almost any one of those great minds would have been living in Europe if it had been possible for them. They didn’t even want to live in New York—how was the Great American Thing going to happen? So as I painted along on my cow’s skull on blue I thought to myself, ‘I’ll make it an American painting. They will not think it great with the red stripes down the sides—Red, White, and Blue—but they will notice it.’” Quoted in Corn, The Great American Thing, pp. 287–288.

EMMA ACKER is associate curator of American art for the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.