Studies of the history of American modern design have largely focused on the influence of central European immigrants, many of whom were instructors at the Bauhaus in Germany and later became heads of prominent architecture and design schools across the United States. Often overlooked is the exchange of design inspiration, starting in the late nineteenth century, that went on between the United States and the Nordic countries of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. A forthcoming exhibition, Scandinavian Design and the United States, co-

organized by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Milwaukee Art Museum, explores Scandinavian design’s enduring impact on American culture and material life, as well as the United States’ influence on Scandinavian design.

Some of the earliest manifestations of American fascination with Scandinavian design are pieces produced by participants in the late nineteenth-century stylistic movement known as the Viking revival. After centuries of looking to the rest of Europe for inspiration, Nordic designers began in the 1880s to look to their own history and heritage. Their work sparked interest and imitators around the globe, and in the United States the most ebullient examples of Viking revival design were on view at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. For the fair, Tiffany and Co. designer Paulding Farnham created a group of presentation pieces that included an eight-handled iron and silver bowl, with a rim embellished with finials inspired by the prow of a Viking ship, now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 7).

Humbler items of Scandinavian design began making their way into American homes with the arrival of Nordic immigrants in the United States, who came in increasing numbers beginning in the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1920s, some 2.3 million had reached the country. Many were highly skilled artists and craftspeople. Some carefully preserved traditional motifs and regional techniques for tasks such as spinning woolen yarn, weaving baskets, and working wood to make everything from furniture to playthings like Dala horses (Fig. 2). The small, hand-carved and colorfully painted horses have been made since at least the seventeenth century in Dalarna, a largely rural area in central Sweden. The horses became familiar curios in the American Midwest, where many immigrant Swedish farmers settled, and surged in popularity in the United States following the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where a giant Dala horse stood in front of Sweden’s pavilion.

Scandinavian professional designers and craftspeople began making their way to the United States in the early twentieth century and many would teach in American schools. One of the most influential was Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, who had earned considerable attention among his American peers for his scheme for a skyscraper that took second place in 1922 in the competition to design a new office tower home for the Chicago Tribune. Two years later, Detroit newspaper chain owner George Booth hired Saarinen to design the campus of what is known today as the Cranbrook Educational Community, a school that, as the Bauhaus did, seeks to foster a union of the fine and applied arts. The program attracted promising American students such as Charles and Ray Eames, Florence Knoll, and Harry Bertoia. As a result, Cranbrook alumni rivaled their teachers in the extent of their influence on modern American design.

Saarinen recruited many leading Nordic artists to the school’s faculty, among them Finnish ceramics artist Maija Grotell, who was renowned for her glaze experimentation (Fig. 13). Grotell took over as head of the ceramics department at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1938. Teaching there for nearly thirty years, she transformed the department from a recreational program into one that produced many prominent professional ceramists and teachers.

Several other schools across the United States hired Scandinavian immigrants as faculty. They included Danish woodworker Tage Frid—who, beginning in 1950, taught furniture making at the Rochester Institute of Technology and later moved to the Rhode Island School of Design—and Finnish weaver Martta Taipale, who taught tapestry making at the Penland School of Craft in North Carolina. In 1954, one of her students was the future fiber artist Lenore Tawney (Fig. 12), who was also focused on sculpture at the time, but would describe her studies with Taipale as “the beginning of my real career.” Hobbyist classes, workshops, and summer schools also served as means for Nordic immigrants to transmit their artistic knowledge to American students.

In the postwar years, Scandinavian companies began to promote an idealized version of the region’s design to American consumers, using terms such as “honest,” “organic,” and “handcrafted”—the latter suggesting that each object was lovingly made by hand, when, in fact, most were produced in small factories. Some American manufacturers had appreciated the elegance of the Nordic design sensibility early on—the first designer for the Knoll furniture company was Danish immigrant Jens Risom, whose 1942 debut design was a variant on the timeless slipper chair, with a gently curving back, splayed legs, and woven upholstery made from rejected parachute straps (Fig. 1)—but had not anticipated the idea of marketing it as such. As Scandinavian design rose in popularity stateside, many American manufacturers boosted the notion of a “Scandinavian style,” producing objects that suggested Scandinavia and marketing them in ways consistent with the ideals of modernity, organic form, and comfort. Sometimes a Scandinavian designer was involved. The Grand Rapids, Michigan, company Baker Furniture invited Danish designer Finn Juhl to create a line of furnishings for Americans that appeared on the market in 1951 (Fig. 3).

Publications and retailers also helped forge the “recognized truth that Scandinavian design has become so much a fact of American life as to be nearly synonymous.” Magazines such as House Beautiful, with editor Elizabeth Gordon at its helm, promoted Scandinavian design continually in the early 1950s. Gordon used the Swedish wall hanging Red Crocus several times, both in tableaux on the pages of her magazine and in exhibitions that she organized (Fig. 4).

By the early 1960s, Scandinavian designs had permeated many Americans’ lives, even those of children, as products from furniture to nursery equipment to baby carriers became emblems of progressive parenting. Toys such as Lego building blocks and the “good luck troll” doll were both products of Denmark (Fig. 5). The latter got surprise publicity after California pilot Betty Miller brought a troll doll with her on the 1963 flight during which she became the first woman to fly solo across the Pacific. Miller carried the doll with her to the White House when John F. Kennedy presented her with a citation. By the next year, trolls were a national sensation, with Life magazine declaring: “The Trolls Take Over.”

On the global stage, design became a medium for a kind of cultural diplomacy between the United States, the Nordic nations, and the rest of the world. During the design, building, and furnishing of the United Nations headquarters in New York City between 1947 and 1952, the three most important chambers were entrusted to architects and designers from Denmark, Norway, and Sweden—a mark of esteem for Scandinavian design prowess. One of the hallmarks of the project was Swedish designer Marianne Richter’s vibrant tapestry curtain provided for the Economic and Social Council Chamber, Sweden’s contribution (Fig. 9). Her geometric design with stripes and sunbursts in bright colors enlivened the otherwise neutral-toned space.

Along with national pavilion displays at world’s fairs, a prominent example of the international dialogue on design ideas came with the exhibition Design in Scandinavia, which traveled through the US and Canada from 1954 to 1957. The endeavor sought to expand the “exchange of ideas between designers and producers on both sides of the Atlantic,” and was organized by the national craft and design societies of Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden, with the various governments serving as patrons. Tapio Wirkkala designed the cover of the exhibition catalogue (Fig. 8)—a graphic interpretation of one of his laminated wood “leaf” trays. Wirkkala designed many variations on the tray, but one example is noteworthy: the one the Finnish designer gave to Stanley Marcus in appreciation for his promoting Scandinavian design in his Dallas store, Neiman Marcus (Fig. 6).

Architects and designers traveled often between the Nordic countries and the United States, furthering the exchange of ideas through formal academic programs, apprenticeships, fellowships, and design projects. One of the more notable examples of transnational design cross-pollination is that of African American artist and designer Howard Smith, who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. He went to Finland in 1962 as part of an arts group tour, and has remained there for the bulk of his career. Committed to making less expensive, more accessible work, Smith designed printed textiles for the Finnish company Vallila with cheerful images of flowers, birds, and landscapes in bold patterns and bright colors (Fig. 11), and, later, ceramics for the firm Arabia.

The turbulent social and political conditions of the late 1960s prompted some designers to think critically and envision a new role for design within society, leading to discussions on issues of sustainability, ergonomic design, and design for all abilities. A central figure of the 1960s design counterculture was the Austrian American professor, activist, and writer Victor Papanek, whose book Design for the Real World, first published in Sweden in 1970, lambasted consumption-driven design in favor of that which embraced environmental and social responsibility.

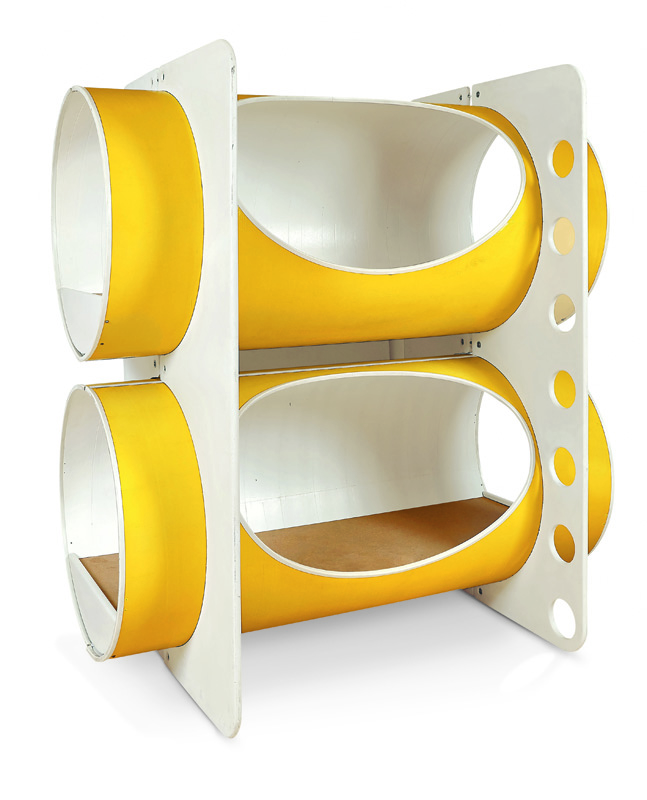

Papanek and designer James Hennessey met in Sweden and later wrote and illustrated the 1973 book Nomadic Furniture while both were working at the California Institute of the Arts in Valencia. The book offered designs for a peripatetic lifestyle, offering a DIY vision of design. It encouraged building one’s own furniture, but also suggested furniture to purchase, including the Big Toobs bunk bed, designed by Californians Jim and Penny Hull, a lightweight, inexpensive piece of furniture and an early model of sustainably produced design (Fig. 14). Such advances have been a hallmark of Scandinavian design’s influence in the United States, since almost the beginning.

Scandinavian Design and the United States was originally scheduled to debut at the Milwaukee Art Museumon May 15 and move to the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art on November 8. Visit mam.org and lacma.org for updates. The exhibition catalogue will be published as scheduled in May by Prestel.

1 Lenore Tawney, oral history conducted by Paul Cummings, June 23, 1971, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. 2 “Finnish Exhibition in Cambridge,” Interiors, vol.119 (August 1959), p. 14. 3 “The Trolls Take Over: Army of Imps Invade U.S.” Life, April 24, 1964, pp. 107–108. 4 Ambassador Wilhelm Morgenstierne, “A Significant Venture,” Norwegian American Commerce, vol.17 (March 1954), p. 7.

BOBBYE TIGERMAN is the Marilyn B. and Calvin B. Gross Curator of Decorative Arts and Design at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

MONICA OBNISKI is curator of decorative arts and design at the High Museum of Art.