When Midnight in Paris: Surrealism at the Crossroads, 1929 debuted at the Dalí Museum in Florida last year, it brought with it a smorgasbord of attractions—paintings by Joan Miró, Salvador Dalí, and René Magritte, sculptures by Man Ray and Jean Arp, photographs and films by André Kertész and Germaine Dulac, and more—all on loan from the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Thanks to Covid-19, those continental visitors are no longer to be enjoyed in person, but a comprehensive online version of the exhibition softens the blow, and has much to add to our understanding of surrealism.

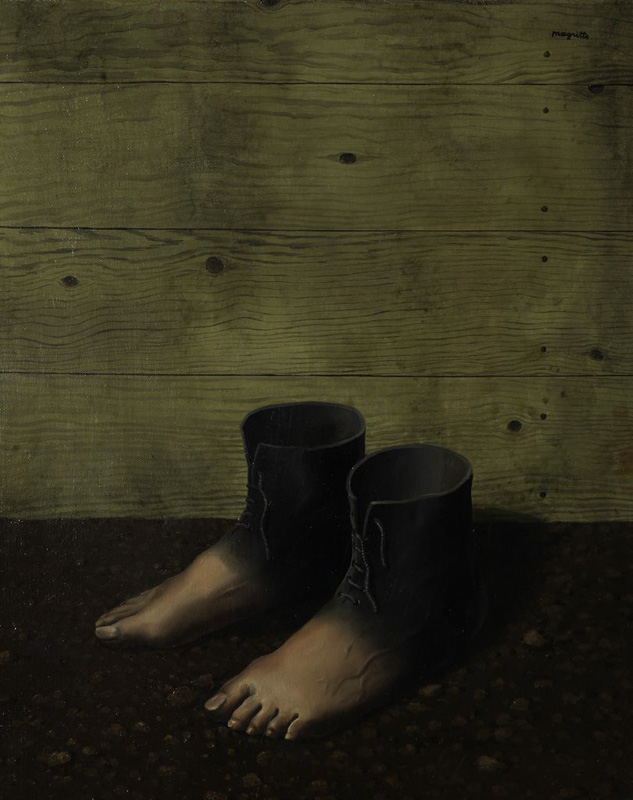

Within the surrealist scene, 1929 was marked by rapprochements as well as quarrels. That year, a special issue of the Brussels journal Variétés, illustrated by the work of artists from both France and Belgium, marked the official joining of the two countries’ surrealists. Such bonhomie did not extend, however, to the respective principals of the movement in the two countries, André Breton and René Magritte. Breton, the Frenchman who’d fired the opening salvo of surrealism with his manifesto of 1924, had been soured against the church by his mother’s strict religious conformity. As Luis Buñuel recounts in his autobiography, when Magritte’s wife, Georgette, arrived at a banquet with a crucifix around her neck, Breton raised such a fuss that he and Magritte didn’t speak again for two years.

Several key surrealist works of art were conceived in 1929, most notably Salvador Dalí’s and Luis Buñuel’s film Un chien Andalou (The Andalusian Dog). A mishmash of purposely disjointed scenes and phantasmagoric and brutal imagery (such as the famous scene of a knife slicing open a woman’s eyeball), the film was met with acclaim by French audiences despite Dalí’s express desire to stick it to “witty, elegant, and intellectualized Paris.” While commonly regarded as not only the best, but also the first surrealist film, in years past Chien has come under attack by proponents of an earlier production: Germaine Dulac’s The Seashell and the Clergyman—a dreamy film about desire turned abject, also on view—which was said to have been overlooked partially because its director was a woman.

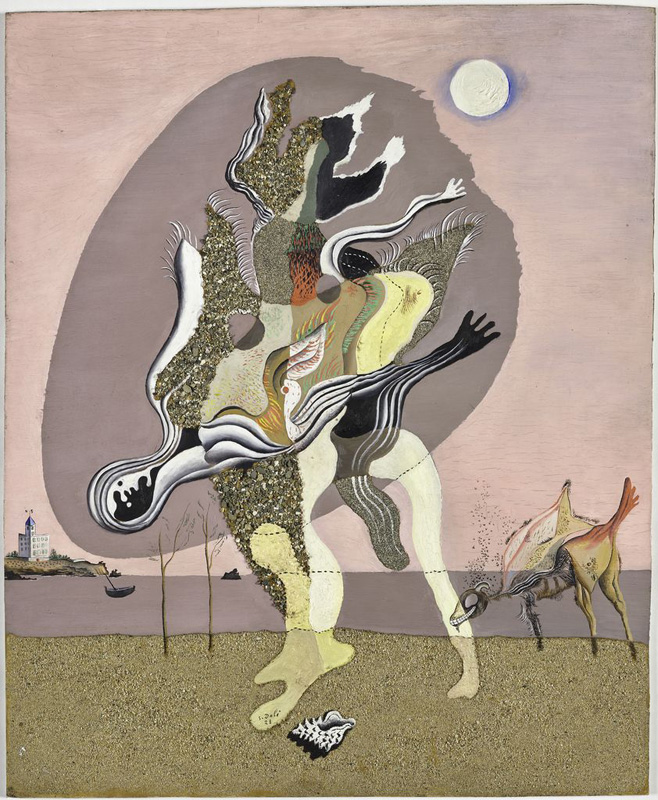

What Un chien andalou had done for film, Max Ernst’s collage novel La Femme 100 têtes (The Hundred Headless Women) did for the book. Made of images from magazines, cut-rate novels, and encyclopedias, Ernst’s book reorganizes them into a loose narrative structure that unfolds across nine chapters. La Femme 100 têtes also marked the first appearance of Ernst’s avian alter ego, Loplop, who would recur regularly in the painter’s work until 1932. Ernst traces Loplop’s origins to an episode from his childhood, when his pet cockatoo died and his sister was born on the same night. With its gesture to the Freudian penchant for seeing the makings of the man in the experiences of the boy, this anecdote would seem to mark Loplop as a by-the-book surrealist creation. But, given Ernst’s satirical bent, one can hardly be sure Loplop isn’t simultaneously a parody of the surrealist program. Breton would one day see fit to feud with Ernst, too.

—Sammy Dalati

Midnight in Paris, 1929—The Online Exhibit • Dalí Museum, St. Petersburg, Florida • thedali.org