August 2008 | The house on the corner of Heather and Union Streets in Manchester, New Hampshire, is surprising. It’s a low-slung arrow, as taut as an Army cot. When Frank Lloyd Wright designed this Usonian house for Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman in 1950, nine out of ten new houses built were ranch style. The Zimmerman House was an upscale cousin to the ranch; now it is estranged. Today, new houses look like a collision of Queen Anne and colonial. This house is not aging. It is getting more modern as the years pass.

Inside the air is a little musty, a little warm and close on the summer day I visit. It is, after all, a closed-up house, a house without the comings and goings of its owners to stir things up. The Zimmermans, who died in the 1980s, left the house and an endowment to the Currier Museum of Art, just across the city.

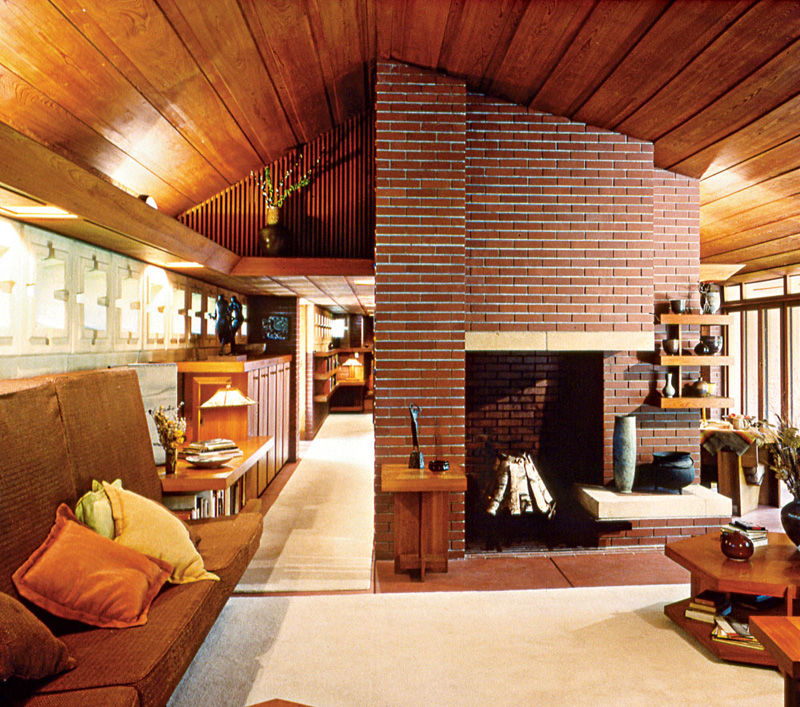

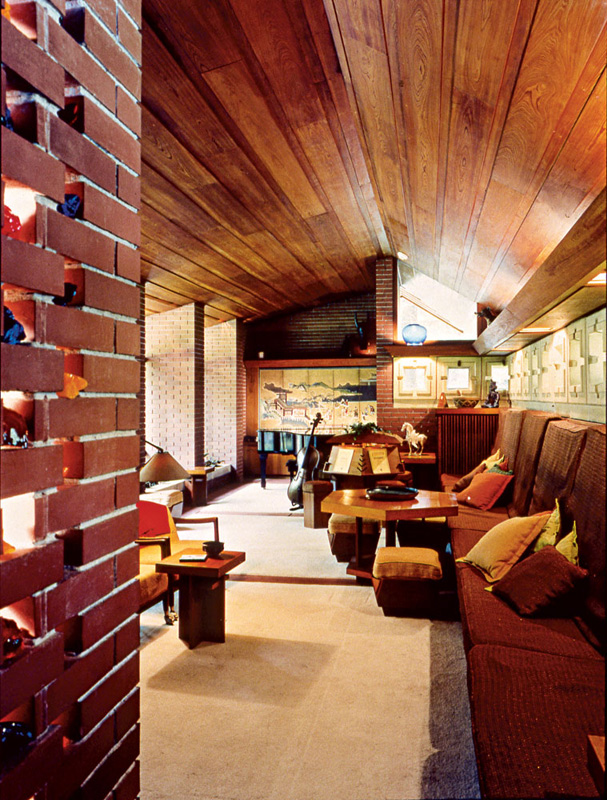

The house is peaceful and calming. The narrow front hall with its low ceiling creates suspense. Entering the house’s one great space, the garden room, you have a sense of arrival. The street seems far, far away. The small backyard seems to be a part of the room and far larger than it is. Tight as a small boat inside, the house opens to the outside in a way that is spacious and liberating. You don’t feel like you are looking out of a box to the outdoors. It is all of a piece. On a small three-quarter-acre corner lot, Wright performed a magic trick.

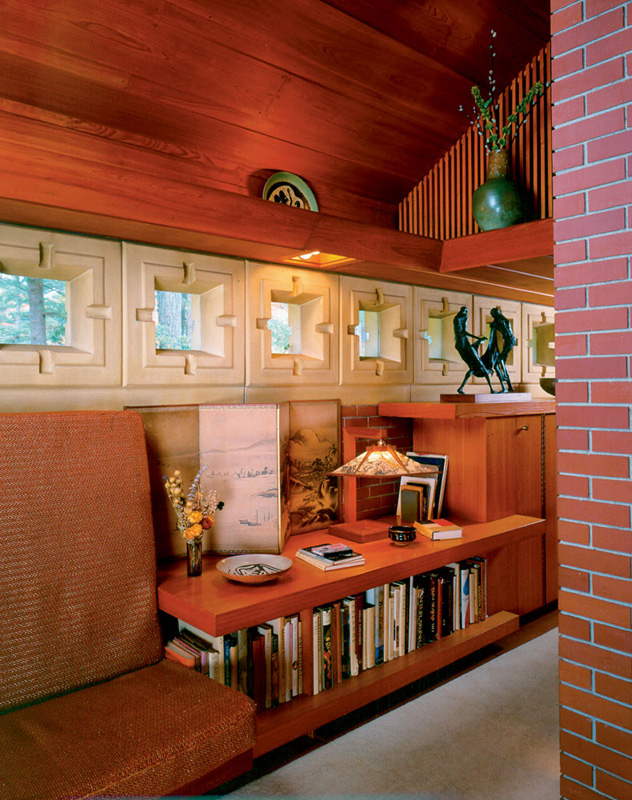

“You are aware of each moment in the house,” Hetty Startup tells me as she shows me around. Startup is a former site administrator for the house. She was at the Currier Museum of Art for twelve years. Only the Zimmermans may have spent more time here. “It is just the most amazing authentic space,” Startup says. “You get that kind of ‘now and now and now’ feeling about nature and light and ephemeral aesthetic qualities. It’s a very rich environment.” She adds, “It’s maybe too rich, maybe too full of things to look at.”

This is a house museum, but without any hokum. Things are not arranged to look as if the Zimmermans have just left. The house is subdued and dignified. It is complete and grown-up in the way few houses or American spaces are.

This house is not that old, but it belongs to a different age. There is no television, no computer, and no winking green and red LED light sources on all the electronic devices. And there’s also no sprawling space, no walk-in closets, media room, or a kitchen with a granite island the size of an aircraft carrier.

It is a small house—that’s what almost all the visitors say. But at almost seventeen hundred square feet, a “Usonian deluxe,” it is actually more than two-thirds larger than the average new house of its day. And yet, the rooms and halls are small. Many Americans now have walk-in closets in their “master suites” that are far larger than the Zimmermans’ bedroom. The garden room is the one grand—six-hundred-square-foot—gesture.

Visitors also find it too dark inside. But that’s because we’ve lost an age-old sensitivity to shadows, says Startup. “We’re overexposed. And we don’t live with enough shadows,” she says, referring to Tanizaki Jun’ichiro-’s famous essay about spiritual repose, In Praise of Shadows (1933). “Look at the way light is modulated in this house by the texture of the materials. It’s so much more restful and peaceful.”

In short, the Zimmerman House just seems alien to many visitors. Of the 2,650 people who don the blue laboratory booties for a tour each year, Startup says that half don’t like it. They wouldn’t move in if you paid them. My own entirely unscientific poll surprised me: People hated it. “That awful house! Those people were prisoners in their own home,” one visitor told me. “He bullied them. Can you imagine?” They thought Frank Lloyd Wright’s patrons were dopey pawns confined to little rooms with everything built in—everything Frank Lloyd Wright and no room for the hapless inhabitant, the homeowner. This is not dislike or indifference, but a kind of white-hot hatred. “It’s a visceral response,” says Startup. The Zimmerman House offended them. Why? Is Wright’s democratic design totalitarian?

House of surveillance

This is not a house to have a fight in; it’s not a house where you’d build a model airplane at the kitchen table (on a hobby board or wax paper). It’s not a house for toddlers with all that plastic Playskool stuff. It’s a house for a refined dinner party with polite talk here and over there. The Zimmerman house is quiet and cultured.

Here the Zimmermans hosted formal evenings of live music each Tuesday. Guests followed the music by reading the score. They sat in the high-backed banquettes in the garden room (see Fig. 9), or tried to. Finding the banquettes as uncomfortable as a church pew, they would lie down. (John Geiger, the Taliesin apprentice who oversaw the construction had suggested a redesign for the banquette-pews.)1

In the Zimmerman House all is out in the open like a New England town common or a meetinghouse—all pews in daylight, all open to view. There is no retreat, no layers of privacy. This house will allow no secrets. People are unnerved by this taint of surveillance. This Usonian house might as well be a lab experiment with two-way mirrors to observe the test subjects.

I had regarded the house as an elegant object, neatly crafted; each item, each brick and art object united in one story. But are houses ever just one story? Is it this we don’t like about new houses and big modern interiors? One idea. We are Play-Doh squeezed through the mold.

House of no improvement

Visitors are put off by the totality of the house. It’s complete. It’s done. You’ve arrived. And if you can’t be happy here and now, you will not be saved by the prospect of home improvement. But home improvement is our domestic Mani—–fest Destiny. There is always a project awaiting—a new bathroom, a kitchen makeover, a new deck, new carpeting, a new addition. Knock out the back wall, push up through the roof. Flip the house and start all over.

But what happens when your house is finished? Now you have to be happy. You have no excuses. A new floor or a new room isn’t going to save you. (This may be what an unfinished house preserves for people—the possibility of arriv-al, the last push through the mountain pass to paradise. If you stop before you’re done, you can’t be disappointed.)

No home improvement, no promise of expansion—it’s un-American. Your house is defined. That means that your life is finite after all. Home improvement is the domestic outpost of our restlessness.

The Zimmermans never would have had a discussion about pushing out a wall to expand the bedroom or getting rid of the Wright furniture for something more modern. They forsook part of our domestic Manifest Destiny—to sprawl across the land, across our lot, and in our house. The Zimmerman House is an arrow into the heart of the do-it-yourself republic. The house is complete. It’s done. Go live your life.

Happy house

The story of the Zimmerman House is not the usual Frank Lloyd Wright saga. It is the Zimmermans’ story. Some visitors mistake them as servants to modernism. But the Zimmermans were happy here for thirty-six years. They gardened; they played music. Yes, they were Wright disciples—“Frank Lloyd Wright nuts” says one volunteer tour guide. They sought his approval for their furniture, dishes, and art (and the letterhead for Dr. Zimmerman’s stationery). They even volunteered to work on the Usonian model house that was built on the future site of New York’s Guggenheim Museum. But this isn’t a shrine. The Zimmerman House is a complete, carefully curated Wright house, but it is not the full-on Oak Park worship. It feels like the Zimmermans’ house. It has a happy home vibe.

In A Work of Art for Kindred Spirits, a short book published by the Currier Museum of Art, what comes across is how at home the Zimmermans were here. One photograph shows them with friends on a Sunday, sitting around reading the Sunday papers. Dr. Zimmerman is dressed in a suit and tie. Mrs. Zimmerman is perched over the paper by the fireplace. (They seem European, even though she was raised as a Kentucky Baptist.) Two friends, sitting opposite, are also reading the paper. Two things dominate the scene—the sprawl of Sunday newsprint, a Niagara that overwhelms all homes—and their dog, a dalmatian. It’s surprising to see a dog here. (What would Wright say? And a dalmatian? If asked, would he have prescribed a dog with earth tones—a chocolate lab or dachshund?) The disorder domesticates the house.

Isadore and Lucille Zimmerman loved their house. (There is a memorial to them in the garden.) They weren’t forever planning additions or thinking of moving. This was it. Their spot on earth. How many others can say that of where they live? “The Zimmerman house is Heaven,” they wrote to their architect. “It is the most beautiful house in the world….No words can express our gratitude.”2 Wright’s architecture performed as promised—it liberated them to live a rich life.

Maybe that is what people can’t accept. The Zimmermans were happy. Here lived two Americans who didn’t want more. They were happy with what they had. Radical.1 Historic Structure Report for the Isadore J. and Lucille Zimmerman House, ed. Carla Lind (Currier Gallery of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, 1989), p. 30.

2 Quoted in Neil Levine, Hetty Startup, and Kurt J. Sundstrom, A Work of Art for Kindred Spirits: Frank Lloyd Wright’s Zimmerman House (Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, New Hampshire, 2004), p. 9.

HOWARD MANSFIELD is the author of several books about preservation including In the Memory House and The Same Ax, Twice.