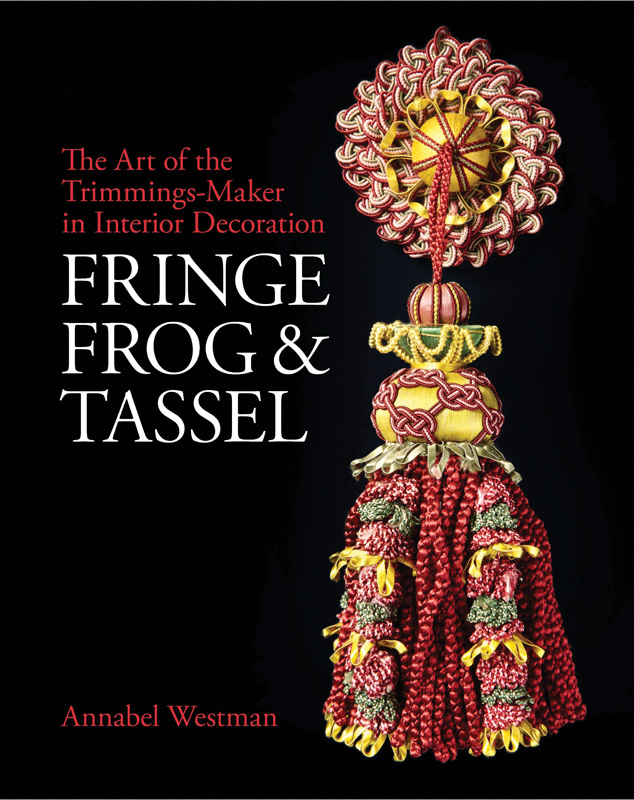

Passementerie, as it’s known in the upholstery trade—braids, gimps, galloons, and myriad other trimmings, almost literally the bells and whistles of interior decoration—is serious business. As we learn from a new book by renowned textile and design historian Annabel Westman. She is also the executive director of the Attingham Trust, the British country estate–based educational organization that has trained legions of academics, decorators, and aficionados in the finer points of decorative arts scholarship. For full documentation of this excerpt, please consult her book, available from Bloomsbury/Philip Wilson Publishers, London.

John Casbert, the royal upholsterer to King Charles II, supplied three very elaborate crimson velvet royal beds in 1662, complete with valances trimmed with metal and silk caul fringes, with one having forty-eight “very rich gold and Silver Buttons and Loopes,” another with eighteen buttons and loops in silver-gilt, and the third “embroidered” with ten dozen gold and silver “Buttons and Loopes.”The effect, totally French inspired, must have been exceedingly rich, with wall hangings and seat furniture to match. However, not all were so lavish and beds with draw curtains and valances usually had twelve (six pairs) or eighteen (nine pairs) of buttons and loops attached to each end of three flat rectangular outer valances.

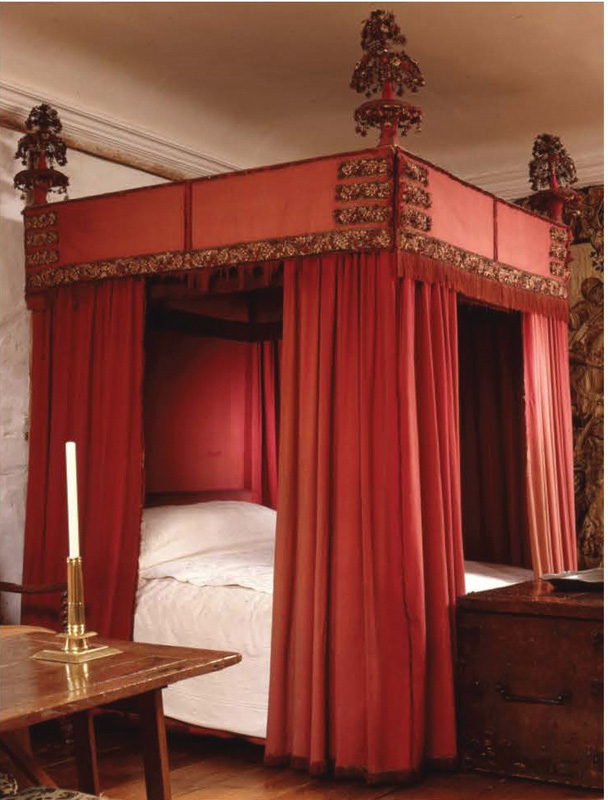

Nine pairs were used on the red bed at Cotehele, Cornwall, which was probably made for the marriage of Sir Richard Edgcumbe to Lady Anne Montagu in 1671 (Fig. 3). As daughter of the 1st Earl of Sandwich, Master of the Great Wardrobe, she would have been fully conversant with the latest court fashions. Three short bands of “vellum and wyre” decoration were attached at each end of the three red wool outer valances, with red floss silk-covered and netted buttons (“olives”) added at the corners. The bands matched the long horizontal decorative trim running the full width of the lower valance edge, creating an elaborate heading to the crimson silk cut skirt below. Such an arrangement is perhaps what Isaac Boddington was referring to when he supplied a “deep fringe wth a french head” for a bed on the royal yacht in 1672.

As the Cotehele example demonstrates, these bands were becoming increasingly elaborate and styled into a variety of shapes, combining different textures and colours using vellum and wire, wrapped in metal thread and/or silk. The individual elements were attached to a close-knit mesh made with fine wire, wrapped tightly in crimson silk at Cotehele, embellished with coils of metal foil and thin strips of vellum, wrapped in cream, black and crimson silk with matching floss poms, to form flower and leaf motifs (Fig. 4). The edges of the bands were worked with turned loops, creating a wire ring with coiled vellum inside. Similar decoration is seen on the finials placed at each corner of the bed to form a towering confection of intricate skill. Each was composed of three wooden tiers, the lower one of wood covered with the same red wool as the bed hangings and the upper two composed of radiating metal armatures. All were hung with festoons and drops of silk-wrapped, tightly coiled wire, rosettes of silk-covered vellum and silk floss tufts in red, cream and black.

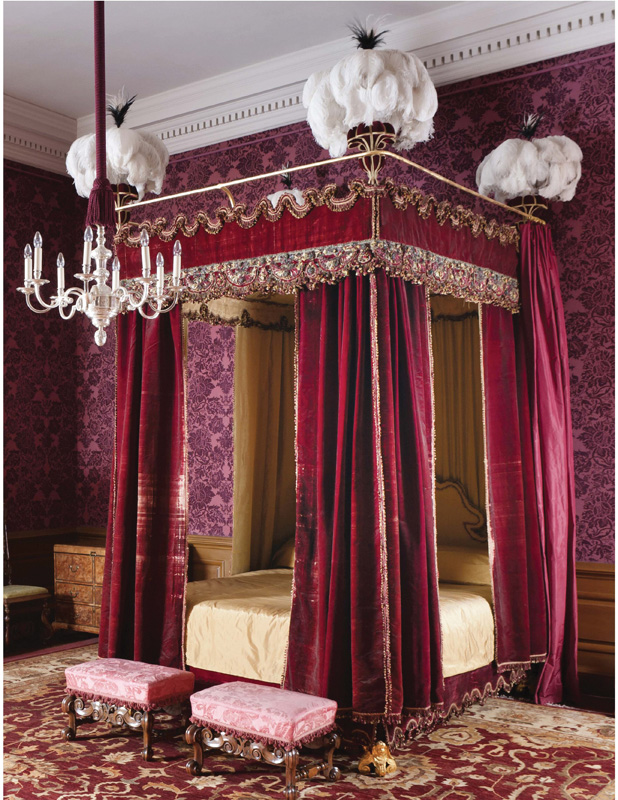

The popularity of this new style provided an impetus for many creative designs, which became much deeper and could incorporate more detail. An early example, on the spectacular King’s Bed at Knole probably made for the Duke of York to celebrate his marriage to Mary of Modena in 1673, was almost certainly made in Paris (Fig. 8). The bed is one of the most splendid to have survived from the period and provides an insight into the magnificence of court fashion. The trimmings echo the colours of the extravagant French tissue (lampas) hangings, of yellow and cream silk enriched with gold thread, and the once strong coral-pink lining embroidered in a floral pattern with gold, silver and black silk thread. Glimpses of the original coral colour can be seen in the trimmings. The valance fringe was made up of compact vellum ribbons and bows, coils and strips wrapped in gold and silver thread and the tufted or tied-tassels of metal thread and coral silk were suspended from double pairs of gold and silver twisted threads.

If a documentary record had survived for the bed, the trimmings would probably have been described as “ffringes of Goldsmiths worke,” indicating where a considerable percentage of the cost lay. Although these Knole examples were undoubtedly supplied by a French passementier, it was not beyond the skill of the lacemen working in England to reproduce them. In 1674, William Gostlin appeared to replace the trimmings “which was taken off his Mats [Majesty’s] damask bed that came out of France” with a supply of “two hundred thirty seaven ounces 1/6 of deep gold colored vallance ffring for the head all embroidr with gold wyer and thirteene ends of Loopes of gold wyer,”at the cost of twelve shillings an ounce. As previously mentioned, metal and silk fringes were charged by their weight, but such a high cost for “gold wyer” is unusual, representing a higher than normal gold content, clearly visible in the quality of these examples. Prices for silver-gilt thread usually ranged from five shillings to nine shillings per ounce, with Gostlin supplying “rich gold and silver purle wyer Knotted fringe” at 8s 6d an ounce for the outer and inner valances of a state canopy, which amounted to the high sum of £566 6s 3d with matching tassels at £1 16s each. At such prices, one can only guess at the cost of the trimmings on the King’s Bed at Knole.

Scalloping the lower edge of the valance fringe (Fig. 6b) was a style that quickly spread. “A buttoned fringe with scalapp vallans to go round the bedd and inner Scolopp suitable, Scolopped Basis Seven payre of Buttons and fringes to tye the curtains” was listed for a bed at Kilkenny Castle in 1675. Many names were given to describe the undulating shape, with “festoon fringe” probably the most common, but other terms like “campaine,” “French head,” “embroidered,” or “raised worke festoon” were also used—often by the same suppliers, to add to the confusion. . . .

The surviving examples provide an essential visual aid to appreciate these descriptions and the variety available. Six pairs of buttons and loops at Ham House are still attached to a rare fragment of watered yellow and black striped mohair, c. 1675–1680, a stylish silk and wool fabric for beds and wall hangings, which was always expensively trimmed. Its wire mesh backing, once wrapped with a light blue-green floss silk, was shaped in alternate circles and larger semicircles using vellum, wire and silk to create rosettes, bows and poms in ivory, dark cream and coral floss silk. The effect is similar to the valance fringe on the bed at Dunham Massey (Fig. 6a) and could answer to a “high purled & tufted vallens fringe” in contemporary terminology, the colours matching the tones of the cream silk embroidered bed lining. Both the Ham and Dunham Massey beds have a top similar to the King’s Bed, trimmed with two layers of “topp tufted” fringe inverted to stand erect with a longer fringe suspended below. Jean Poictevin referred to this undulating shaping as “Cutts and Scollups” in 1677.

This talented upholsterer supplied a similar bed with a “cut head band [. . .] french fring and 9 pairs of loops” to William Russell, 5th Earl and 1st Duke of Bedford at Woburn Abbey in 1680. In the same year, Thomas Leigh, 2nd Baron Leigh of Stoneleigh, Warwickshire, was charged £5 “ffor a Sett of Scrollupt Lathes,” the shaped wood backing necessary to support the “ffestune fringe of ye newest fashion / wth 9 pr of Buttons and lupes in crimson, black and white silk at £4.10.” John Ridge, another London upholsterer, provided a similar “set” still surviving on the “crimson and gold velvet bed lined with yellow satin,” made for the Duke of Hamilton’s apartments at the palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh, in 1682. Other Scottish noblemen ordered similar designs, one with “A fine silk freinge of Imbroidered gimpt work with twelve loups conform upon the corners of the bed” decorating the velvet bed lined with gold coloured satin made for William Douglas, 3rd Earl and 1st Duke of Queensberry, Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, at Drumlanrig in Dumfriesshire.

Usually these complex valance fringes were combined with buttons and loops, ideally suited to the flat rectangular valances, but this intricate ornament, which had been fashionable for over a century, had passed its peak. They are missing from the crimson velvet bed with its “mixt Silver Gold and Silk Vestoone great Fringe upon the Vallins” (Fig. 6), which the Duchess of Somerset had bequeathed to her niece, Mary Langham, wife of Henry Booth, 1st Earl of Warrington of Dunham Massey. They are also not found on the remnant of another remarkable festoon fringe at Burghley House, Lincolnshire, which originally came from one of several “Imperial” bedsteads supplied to John Cecil, 5th Earl of Exeter and his wife, Lady Anne (née Cavendish) and is now, in altered form, on the black and yellow bed. As early Grand Tourists who visited France and Italy on several occasions, they were fully in touch with the latest fashions. They would probably have been quite aware that beds were becoming taller during the 1680s and cornices were being introduced, some elaborately pierced and carved. The new style can be seen on another bed at Burghley House, probably made for Lord Exeter’s own bedchamber (today called Queen Elizabeth’s Bedroom), c. 1685. The bed, once hung with blue patterned velvet, still retains its embroidered lining and spectacular valance fringe of more solid construction, vibrant in its red, pink, green and gold-coloured silk-wrapped vellum decoration to match (Fig. 5). The large scrolls and coiled wire have infills of embroidered silk on a turquoise satin ground attached to a valance suspended from a deep moulded cornice (Fig. 7).

1 The weight of the trimmings was supported by buckram, the usual backing for valances, which often acted as the lining too. It was more pliable than the gummed buckram canvas available today. 2 Finials of similar design survive on the yellow and black bed at Burghley House and also at Skokloster Castle, Sweden. 3 The last mention of buttons and loop decoration in the Great Wardrobe accounts was in 1683. They were used on Sir Dudley North’s bed, originally at Glemham Hall, Suffolk,c. 1685. 4 The valance fringe on the embroidered bed in the Black and Yellow Bedchamber has been altered and the original wire mesh backing has been replaced with white buckram. Several sections have been reworked, showing a less sophisticated hand, with the scrolled vellum strips, for example, having been replaced with coloured cord. The tied-tassel fringing has also been remade. As the bed was listed in the 1763 inventory, the work was probably done in the early 1760s. The bed was altered again in 1838, the date embroidered on the tester. 5The bed was conserved by Sheila Landi in the early 1990s and the curtains and linings replaced.