Edward Gorey’s genre-defying illustrations meet an unexpected medium.

This year marks the centennial of the birth of the illustrious artist and author Edward St. John Gorey. It is also a quarter of a century since his death in 2000 at the age of seventy-five. To mark these milestones, New York Review Books has brought out From Ted to Tom: The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey. It is as eccentric a volume as one would expect from the creator of The Wuggly Ump, The Glorious Nosebleed, and The Epiplectic Bicycle.

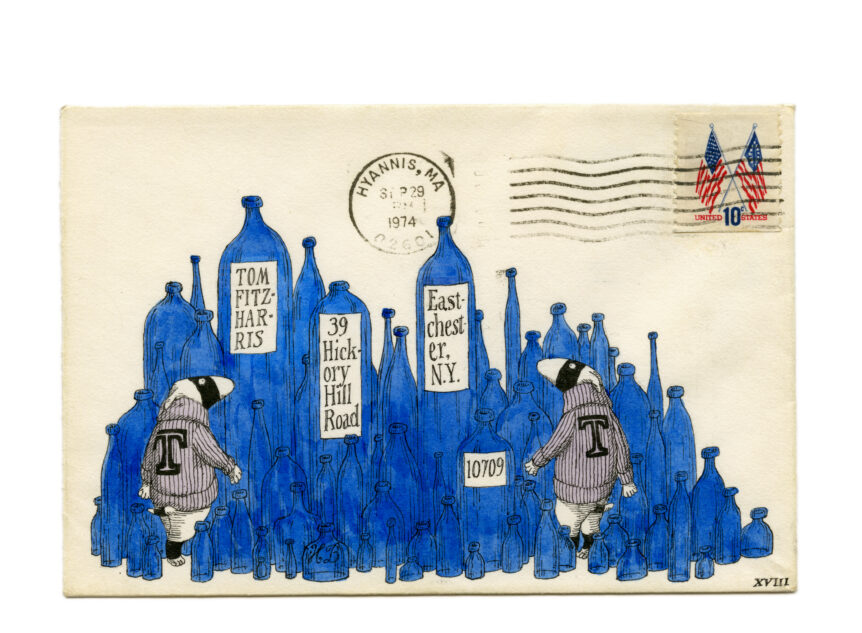

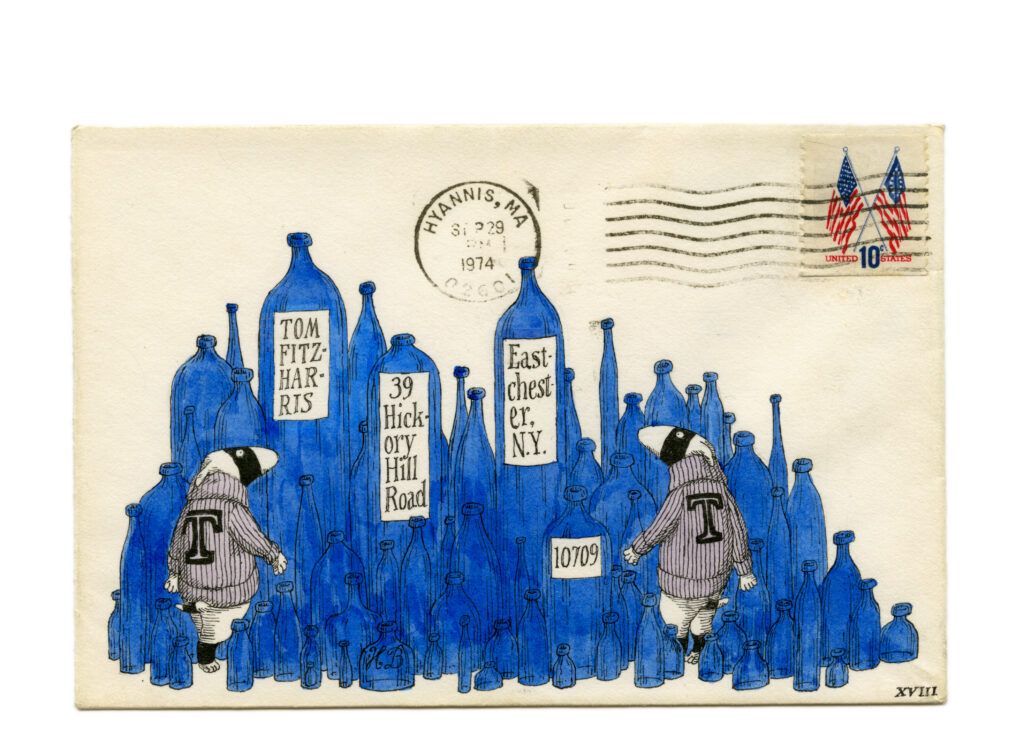

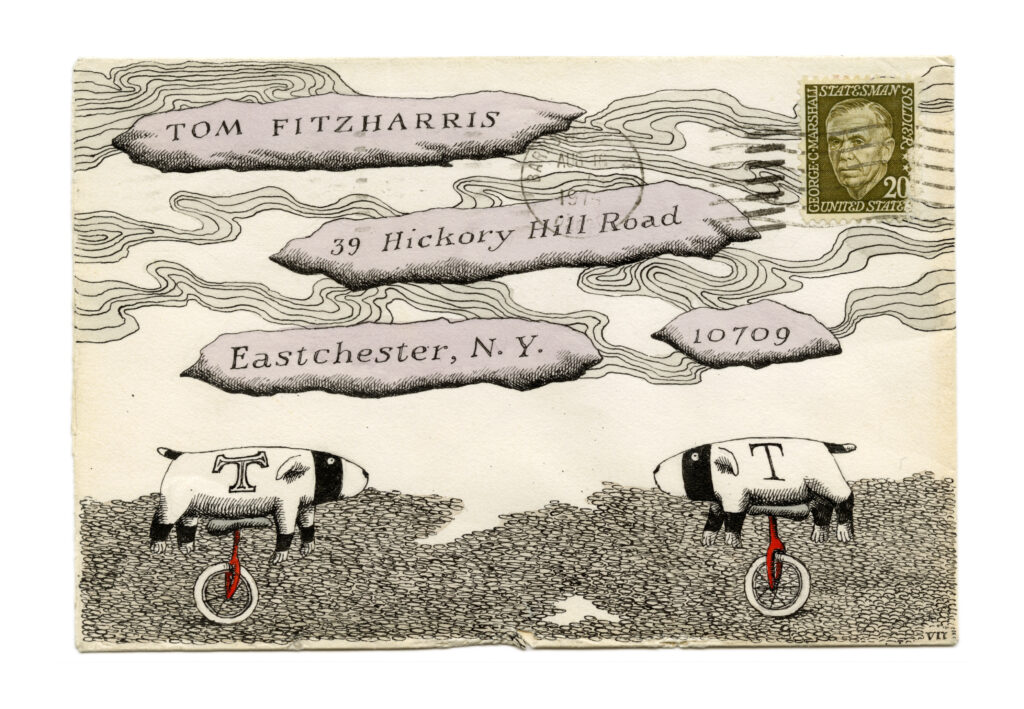

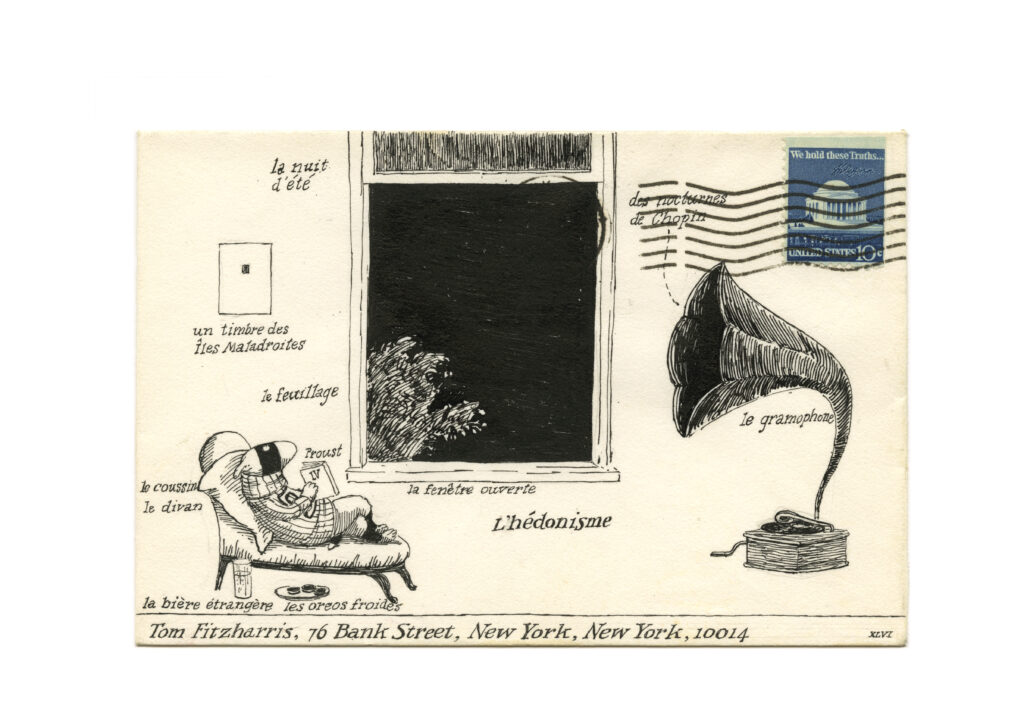

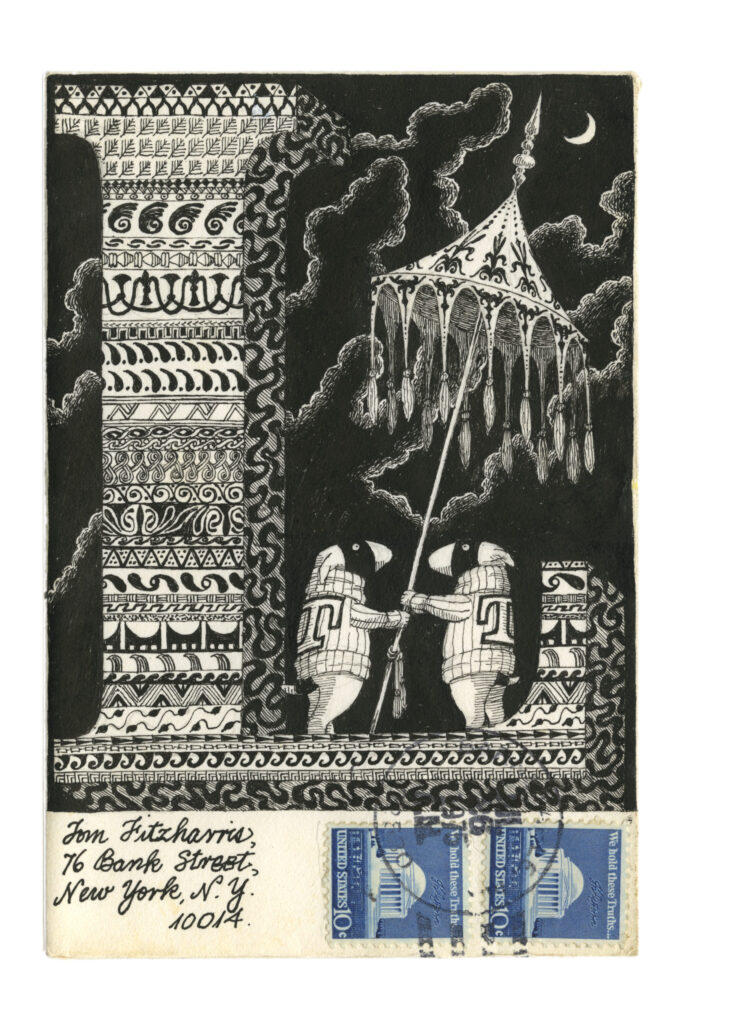

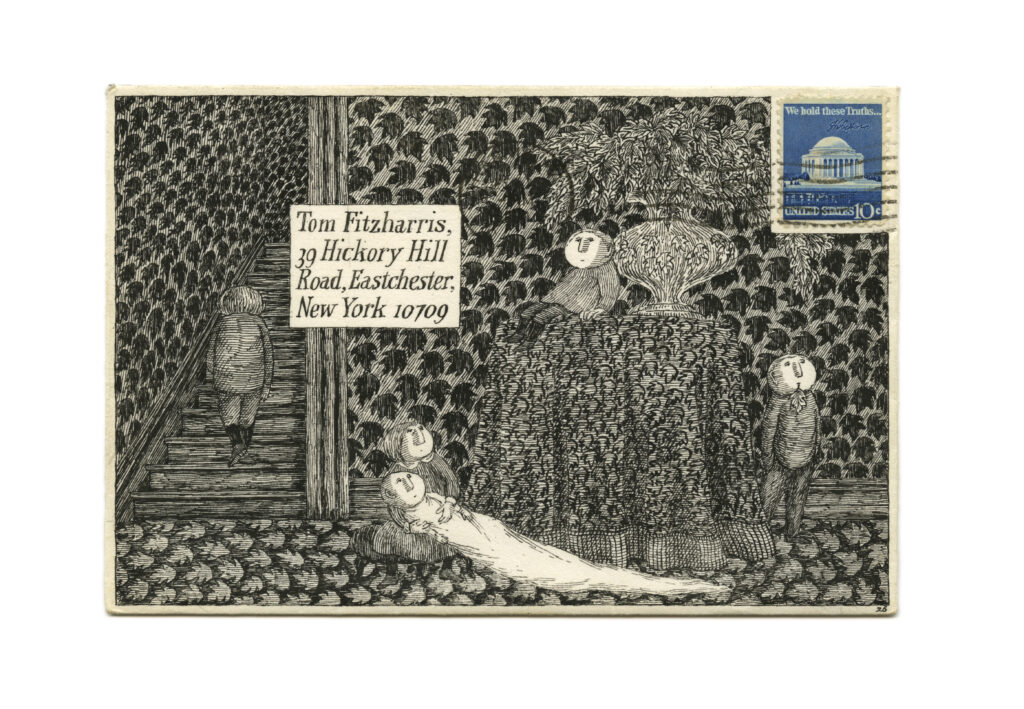

The book reproduces the front and back of fifty illustrated envelopes in which, between 1974 and 1975,

Gorey—Ted—sent weekly letters to his friend Tom Fitzharris, who has edited the volume and provided an introduction. It also includes abundant excerpts from the letters, which, in their slyly elusive way, provide a valuable self-portrait of the artist. And yet, in their totality, they do little to penetrate that carapace of irony behind which Gorey confronted the world, or, in the present case, one of his closer friends.

As for Fitzharris, he is reticent about himself other than to inform us that “Tom Fitzharris was a close friend of Edward Gorey in the 1970s. He currently lives in New York City and gives tours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.” We also learn that, although Gorey rarely traveled beyond the United States, he and Tom once visited Scotland together. As to why their correspondence—of which only Gorey’s half appears in the book—abruptly ended after one year, Fitzharris himself can offer little clarification: “At some point,” he writes, “I just stopped hearing from Ted.”

Most of the letters were sent from Gorey’s home in Cape Cod to Fitzharris’s in Eastchester, New York, or Lower Manhattan, and each envelope must have come as an extraordinary gift to its recipient. Gorey was an artist whose inscrutable images often consisted of the painstaking accumulation of thousands of lines, often from his Rapidograph pen, and occasionally aided by a colored wash. A few of the envelopes depict the artist’s more familiar subjects: despairing heroines, moribund children, Edwardian men at their leisure.

More often, however, they depict one or several dogs that Gorey, despite being a famous cat lover, seems to have chosen as stand-ins for himself. We find them lounging around the edges of the envelopes in varsity sweaters, riding unicycles, or inexplicably airborne.

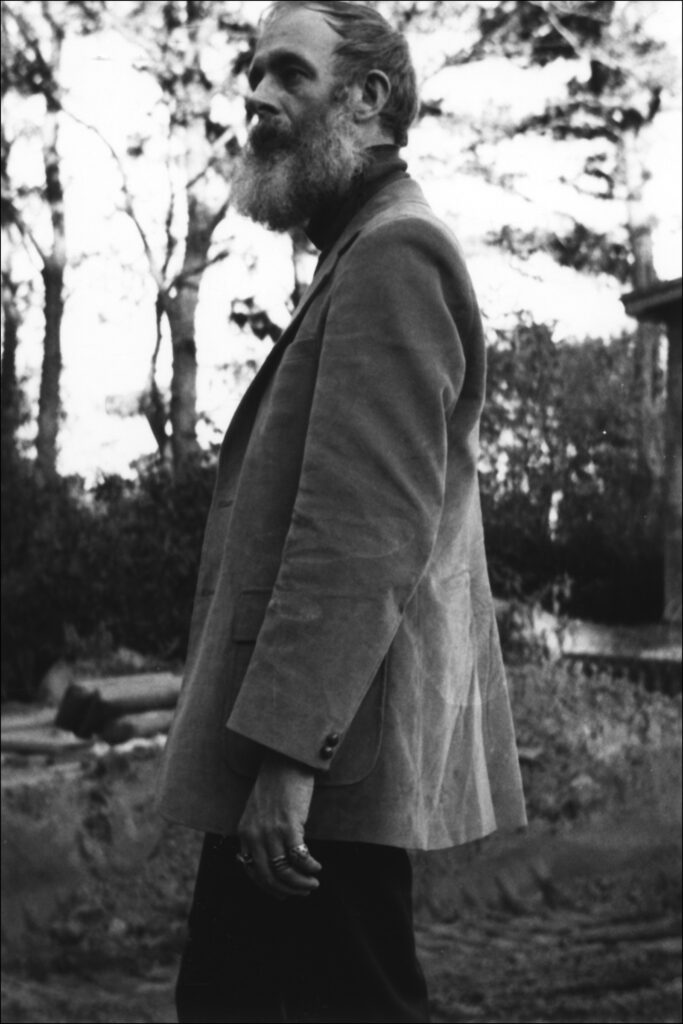

Although Gorey was born in Chicago and graduated from Harvard with a degree in French literature, he reinvented himself in strict accordance with his most extravagantly Europhile whims, and if the world wished to look over his shoulder and see the results, he was more than happy to let it do so. He truly was an eccentric, unlike many people who merely pretend to be. Anyone who lived near Lincoln Center in the 1970s probably passed him more than once, walking like a one-man parade in a great beaver-skin coat on his way to ABT—the American Ballet Theater. With his fastidious beard, he resembled several kings of England, especially those named Edward. His resurrection of a vanished Europe of upholstered aristocrats, dying maidens, and grand opera could only have come from the mind of an American who, by choice, had rarely if ever visited the continent.

Instead, after many years in Manhattan, he spent his final decades secluded in his house on Cape Cod, amid his books and operatic recordings, returning only occasionally to New York to see live performances. I am not sure that anyone has ever brought together in the same sentence the names of Edward Gorey and Robert Crumb, but the similarities are there.

Both artists have wielded their pens with consummate skill to re-create a vanished world, even though the worlds they revived were very different, as was the spirit in which they revived them. Whereas Crumb gleefully displays a raunchiness that borders on obscenity as he revives the America of his childhood in the 1950s, Gorey, about a generation older, looks back to the European Belle Époque and to a vanished world of arcane refinement that he, as American as Crumb, had never known. But such are the mastery and intensity of both artists’ visions that they seem perfect and total unto themselves.

Although Gorey was never a comic book artist, as Crumb is, the marriage of word and image is no less essential to his art. Like the comic book artist, he has a masterful and endlessly inventive sense of graphics, of the placement of the image on the page, or in this case the envelope, and of its interaction with the words. But if Crumb prefers mid-century working-class lettering, admirably punchy and functional, Gorey lovingly be-labored each of his letters, ennobling them with a full complement of Europhile serifs.

Beyond their formal beauty, all the lines and letters are consolidated into a world view that is ultimately far happier and far less earnest than the covert seriousness at the core of Crumb’s art. If there is one contemporary cultural figure whose spirit most closely resembles Gorey’s it is Tim Burton. Darkness and death and an alienated past haunt the work of both men, but in a way that is oddly healthy and life affirming. Death, the great leveler, is reduced to a fashion statement, a winsome posture, in the works of both men.

As an artist Gorey surely has his limits: essentially, he does only one thing, but within that tiny domain his mastery is absolute. His aesthetic universe consists of archly ironic depictions of stylized humans, animals, and creatures drawn from his imagination. The beauty of these images results not from any single line—as one might expect from an expert draughtsman—but from the totality of those lines taken together. Aside from a few voids plugged with a colored wash, the warp and weft of Gorey’s thousand little lines constitute a whole that is mysteriously satisfying.

In purely formal terms then—and one suspects that Gorey, a genuinely modest man, would accept this assessment—his art is obviously minor. As his rhyming texts are light verse, so his exquisite drawings are something other than high art. But in a sense they are something even better than that. Through word and image, Gorey shares with a select group of artists, writers, musicians, and filmmakers the ability to conjure out of nothing an alternate universe that we gladly enter.

This sort of art adds something as valuable as it is inessential, one more option of experience that was not there before, that we did not even know we needed until we finally encountered it. In the process, the universe has been ever so slightly expanded, and it has been improved.

Except for the photograph of Gorey shown on this page, the images in this article are from From Ted to Tom: The Illustrated Envelopes of Edward Gorey, by Edward Gorey, edited and with an introduction by Tom Fitzharris, published by New York Review Books earlier this year, and are © 2025 by the Edward Gorey Charitable Trust; courtesy of Tom Fitzharris. For more information about the book, visit nyrb.com.