The image of New London, Connecticut, Native Charles Holt in Figure 1 was “taken” by his cousin, the talented miniaturist Mary Way in the form of a miniature-in-locket, a standard memento of the time meant to be worn close to the heart1. It is not known whether he commissioned the portrait as a gift for his soon-to-be wife Marry Dobbs, or whether Way presented the portrait to Holt as a personal token. In the image the artist has portrayed Holt wearing what appears to be an American militia uniform; inscribed “Mary Way,/fecit/New London,/Feb. 18th,/1800” on the back, the portrait is the only known signed and dated work by Way (Fig. 2). Although Mary Way and her sister Betsy Way Champlain produced many images of men of various ages in and around New London from the late 1790s through 1825 (in Betsy’s case, carrying on alone after 1820 due to Mary’s progressive visual deterioration), this is the only one in military dress.

At the time of the portrait Holt, founder of the local Bee newspaper, was awaiting imprisonment for alleged sedition against the Federalist-run government, and the portrait is remarkable for the way in which it conveys the artist’s sympathy for her subject. It was both a personal and political statement in support of Holt’s stand for the basic freedoms inherent in the United States Constitution, and was consequently in direct opposition to the views of Way’s predominantly Federalist New London clientele. So, why did she sign and date this miniature? And why does it depict its subject in military dress?

As the owner and publisher of the Bee newspaper between 1797 and 1802, Holt’s original intention was to remain politically neutral in the partisan political climate of New London (and Connecticut for that matter), where “God was a Federalist, and Republicans never won a statewide election, or even a congressional seat, until after 1818”.2 He expressed his initial position in the paper’s first issue on June 14, 1797: “The Publisher of this paper is determined that his paper shall be, with respect to political disquisitions, impartial in every sense of the word.” And yet, when he published “a few mild pieces from the area’s hopelessly outnumbered Republicans, he found himself boycotted and reviled.”3 He was denounced by the Federalist faction, marginalized financially by local businessmen and, as he noted in his editorial on June 20, 1798, styled a “Jacobin, a Frenchman, a disorganizes and one who would sell his country.”

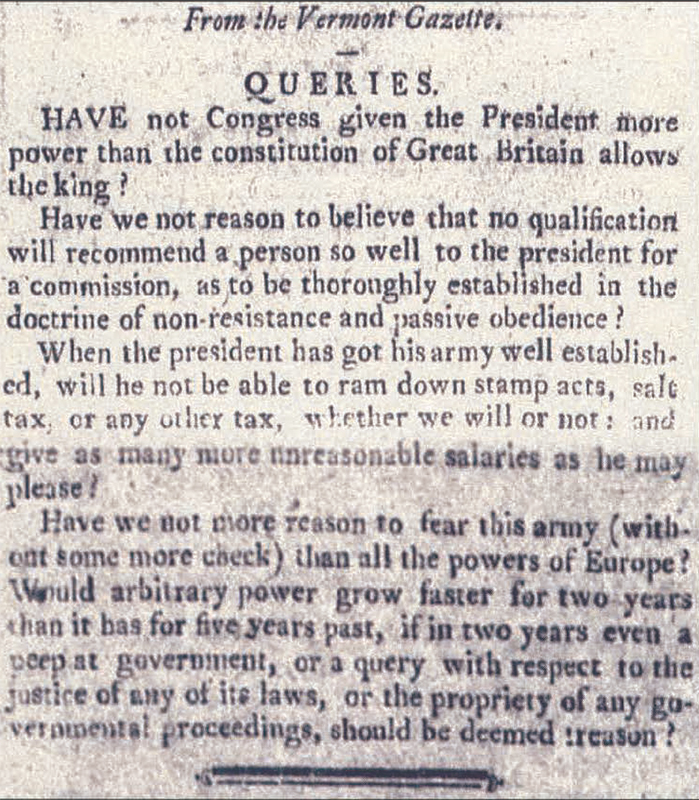

Holt’s editorial tone changed after the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798-1801, which limited freedom of speech and the press by criminalizing criticism of the government. The act also redefined the First Amendment of the newly ratified Bill of Rights: “if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published…any false, scandalous and malicious writing… against the government of the United States…with intent to defame… or to bring…into contempt or disrepute or to excite against… or to stir up sedition … then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States…shall be punished by a fine…and by imprisonment.” The passage of the Sedition Act prompted an angry editorial from Holt in the June 20,1798, edition of the Bee “If the Constitution of the United States was not considered by the majority of the House of Representatives as a mere dead letter… they would never have ventured to bring in a bill directly contravening one of the most essential articles in the code of freedom…namely, liberty of speech, printing and writing.” Impartial no longer, he eventually went on to express the rationale for his changed position in a December 5, 1798, commentary: “There are generally two sides to every subject. To the public opinion, in a free country, there ever will and should be. And it is the duty of an impartial printer to communicate to the public on both sides freely…The public may therefore rest assured that so long as my brethren in this state print on one side only, so long will I print on the other.”

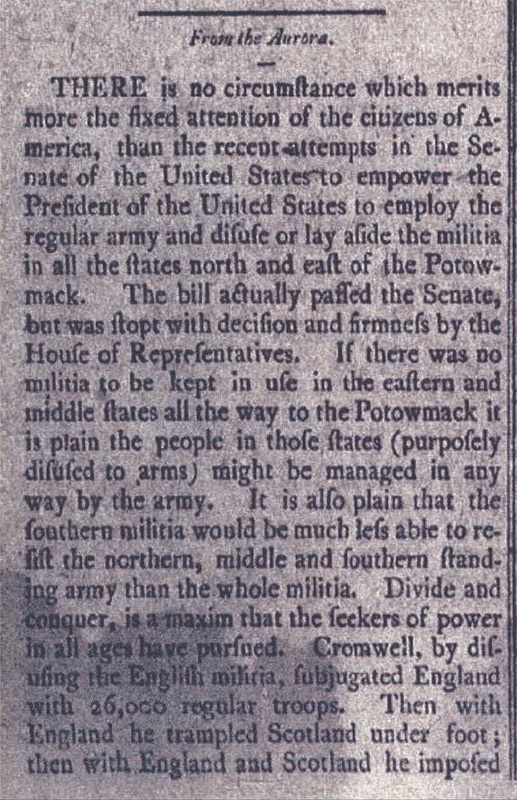

By late 1798, with the Sedition Act in place, Federalist authorities were monitoring Holt, in part because of his opposition to the concept of a standing army evident in an article reprinted in the Bee on July 25, 1798 (Fig. 2). And then on September 17, 1799, a Connecticut grand jury charged him with seditious criticism for publishing a letter from Danbury that asserted the prevailing Republican view that the planned Provisional Army, commanded by Alexander Hamilton, was intended to become a standing army whose chief purpose was to police any implied form of verbal or written political unrest.

Responding to the proposed army’s intrusion into the basic freedoms of speech and the press, Holt had written an editorial suggesting that citizens reconsider sending their sons to join the Army. On September 21 he was arrested and brought to Hartford for arraignment. His subsequent trial and conviction on April 12,1800, carried a three-month sentence and a fine of $ 5 5 0. Imprisonment followed immediately. In a coincidence of history, Holt, who had been labeled by the Federalists a “Jacobin-Frenchman-Disorganizer,” was released on or around July 14, 1800, the eleventh anniversary of the storming of the Bastille and the beginning of the French Revolution.

With its expert facial modeling and precisely rendered detail illuminating the handsome and dignified spirit of her subject, the portrait of Charles Holt shows Mary Way at her best. Holt is portrayed in a militia-type uniform, although there is no record of his Connecticut militia service through the end of 1800.4 The costume appears to be the invention of Mary Way, a symbolic rendering of her sympathies with her cousin. The high-collared blue uniform with red highlights and white epaulets is reminiscent of the French Revolutionary uniforms of the early 1790s. However, according to the military expert Donald Troiani, the style was also worn by “an American officer dating about 1790—1795.”5 Troiani points out that the mixed metal types— apparently brass buttons and hat cord (Artillery) and silver epaulette (Infantry)— are more suggestive of a militia than a formal army. In view of Holt’s aversion to a standing army and his published support of the militia (see Fig. 3), this attribution appears correct. The applied fabric “chapeau bra s” appears bicorn rather than tricorn in design as in the Napoleonic troop wardrobe, but is also similar to the smaller “cocked hat” worn by troops in the American Revolution. It is thus an amalgam of two Republican ideals.

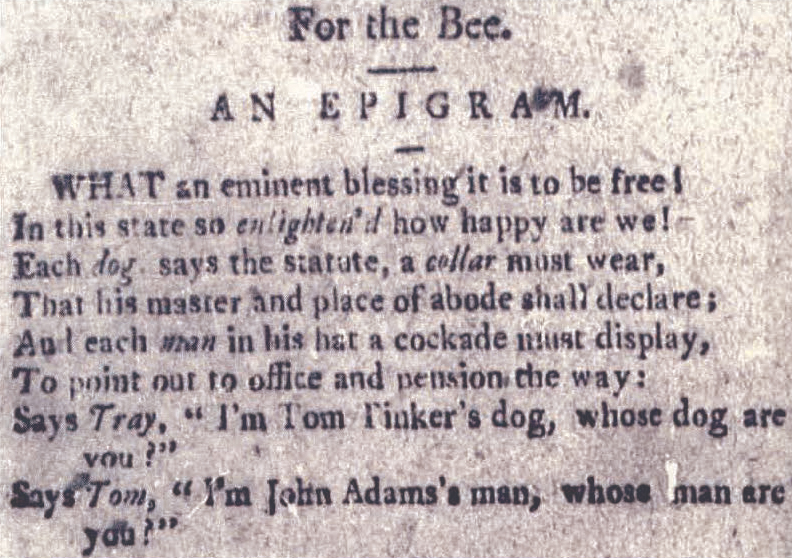

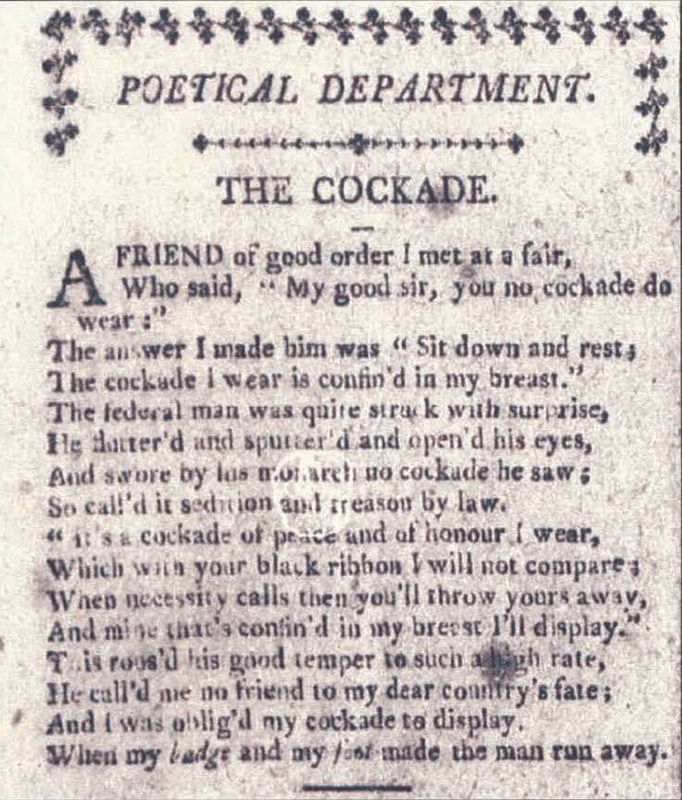

The black cockade is of particular interest (Fig. 6). According to Troiani, “black is standard from the period 1779 thru 1815 for regulars and the militia.” However, by the end of the eighteenth century, Federalists had appropriated the black cockade as their patriotic hallmark with a resulting Republican backlash.6 Charles Holt, who had published two satirical anti- Adams/Federalist pieces (Figs. 4, 5), is shown by Way re-appropriating the black cockade. Her use of this decorative device seems to turn it into a criticism of the Federalist custom—a statement by Charles Holt that “I’m [not] John Adams’s man, are you?”

Mary Way’s depiction of Holt’s somewhat theatrical apparel with its references to the French Revolution and the rights of man appears to express her sympathy with her cousin and the Republican cause. By specifically dating the miniature, she draws attention to Holt at the moment when he was under legal attack by the Federalists. Moreover, by giving her cousin a military presence, she suggests his role as an esteemed leader in the cause of free expression. The creation of this intimate locket can be viewed as an expression of Way’s opposition to the political views of the majority of her New London clientele and her state’s Federalist tradition, making it a revolutionary statement of her own.

1Brian Ehrlich, “Evaluating the Shared Artistry: Mary Way and Betsy Way Champlain,” Antiques and Fine Art, vol. 13, no 3 (Autumn 2014), p. 130. 2Jeffrey L. Pasley, The Tyranny of Printers: Newspaper Politics in the Early American Republic (University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville, 2001), p. 134. 3Ibid., p. 135. 4A Charles Holt entered the Connecticut militia with the rank of lieutenant in October 1801, according to information courtesy of Services for History and Genealogy, Connecticut State Library, Hartford. 5Information specific to early American uniforms supplied by Donald Troiani, artist, historian, collector, and consultant in aspects of militaria from the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, Civil War, and World War II. 6According to the entry for “Black Cockade” in John J. Lalor, Cyclopaedia of Political Science (New York, 1899), “Throughout the American Revolution a black cockade…was part of the continental uniform. When, therefore, the intense war feeling against France, roused by the dispatches from the X.Y.Z. Mission, became useful in politics, the black cockade was mounted by the federalists, partly as a patriotic badge, and partly as a popular reminder of the tricolor, which the republicans had been accustomed to wear as a mark of affection for France. The new badge provoked the anger of the more violent republicans…. Ill the decadence of the federal party, ‘black cockade federalist” became a common term of reproach.”

BRIAN EHRLICH is an independent researcher working and writing in Connecticut.