The exhibition entitled High Styles: Twentieth-Century American Design, currently on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, is the first comprehensive showing of American decorative arts and industrial design of this century. The display of more than 270 objects and its accompanying catalogue compose a primer of American design. They contain many surprises for all but the most knowledgeable scholars, for the exhibition is indirectly dedicated to remembering those left out of most standard histories of design in the twentieth century. The great stars of American design are of course represented—Louis Comfort Tiffany (see Pl. IV), Frank Lloyd Wright (see Pl. V), and Charles Eames (see Pl. IX)—but so are designers whose work is rarely seen, among them Karl Kipp (1881–1954), Milo Baughman (b. 1923), and Ilonka Karasz (1896–1981). It is the inclusion of just such figures that enriches our understanding of twentieth-century American design, for a number of them created beautiful and innovative objects directly inspired by the architecture and furniture of the past. To call attention to their work is part of a general revisionist tendency in the last decade. Architectural and design historians are coming to accept and study more than the international style, the arts and crafts, streamlined moderne, and art deco—all “modernist movements.” This more balanced approach, however, illuminates a constant in American design of this century: the tension between design directly inspired by the past and that which is not inspired by the past.

Perhaps more important, the exhibition and its catalogue raise issues that broaden our understanding of the American arts. The first of these is, What is high style and how does it differ from what is commercially popular? According to the introduction to the catalogue the term “high style” should be “reserved for the superlative—for the most important, the ultra-fashionable, the unusually dramatic.”1 For the most part, the choice of objects in the exhibition is consistent with this definition. Other issues raised by the show are, What is American style and how has American design used the past?

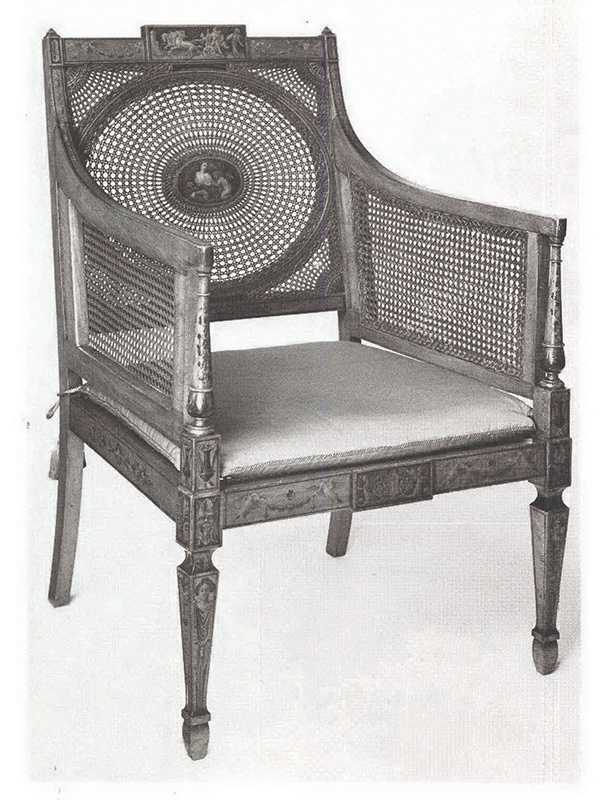

The World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1S93 synthesized trends in American arts of the preceding decade and brought the American Renaissance style to the attention of the public. The fair’s buildings were designed by leading American architects of the day, including Richard Morris Hunt and McKim, Mead and White, most of whom had studied at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris or were influenced by its attitudes. Their buildings were inspired by European Renaissance and baroque architecture, but they were reformulations rather than copies. The result was a style that was immediately adopted by major institutions and the rich, for it suited the aspirations of Americans who were beginning to sense their economic and industrial vigor and their potential influence on world politics. The same sources used by the architects of this style — with the addition of eighteenth-century neoclassicism — inspired the designers of furniture and other decorative arts objects of the period. The chair of about 1905 shown in Figure 1, for instance, is modeled on an English Sheraton example and reflects the growing taste for simplicity and neoclassicism at the turn of the century that was fostered by Ogden Codman Jr. and Edith Wharton in their Decoration of Houses of 1897. There they advocated interiors in which proportion, architectural unity, and propriety were emphasized.2 Renaissance and neoclassical furniture and architecture provided the preferred vocabulary. This approach created interiors of clarity, simplicity, and lightness emphatically different from those of the Victorian era. It stimulated other designers, among them Elsie de Wolfe, who carried these ideas into the twentieth century and modified them in her work as an interior designer and a writer on design.

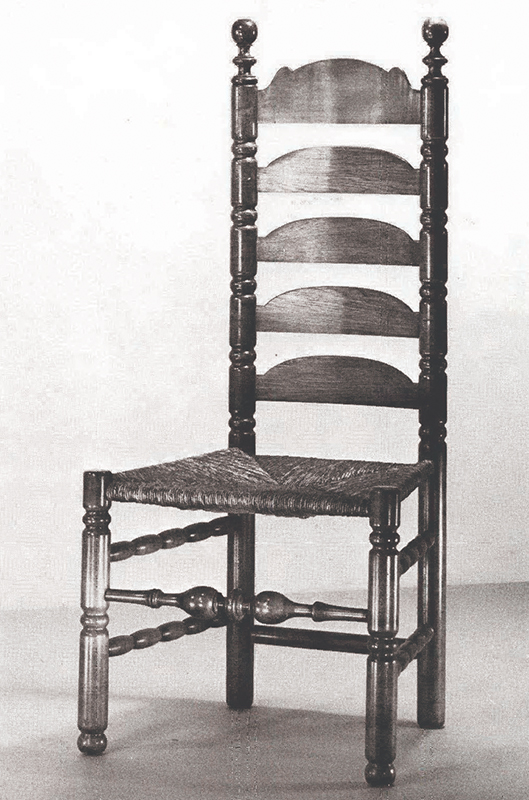

Simultaneously, American taste makers were also partisans of colonial furniture—an interest in all styles predating 1820 that was revived by the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. After the turn of the century, scholars began to differentiate between the various phases of the colonial style. Distinguished among these scholars was Wallace Nutting, a collector and restorer of houses as well as a manufacturer of colonial revival furniture beginning in 1917. He was extremely important in the revival of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century American furniture, and his Furniture of the Pilgrim Century (1921) has remained a classic. Nutting felt that furniture in the Pilgrim style was a legacy of the Middle Ages and he, like the theorists of the arts and crafts movement, saw the ideal social structure as the medieval one in which there was a close connection between the worker and the object he produced. In fact, the taste for the simple lines of American colonial furniture prepared the public for the arts and crafts movement.

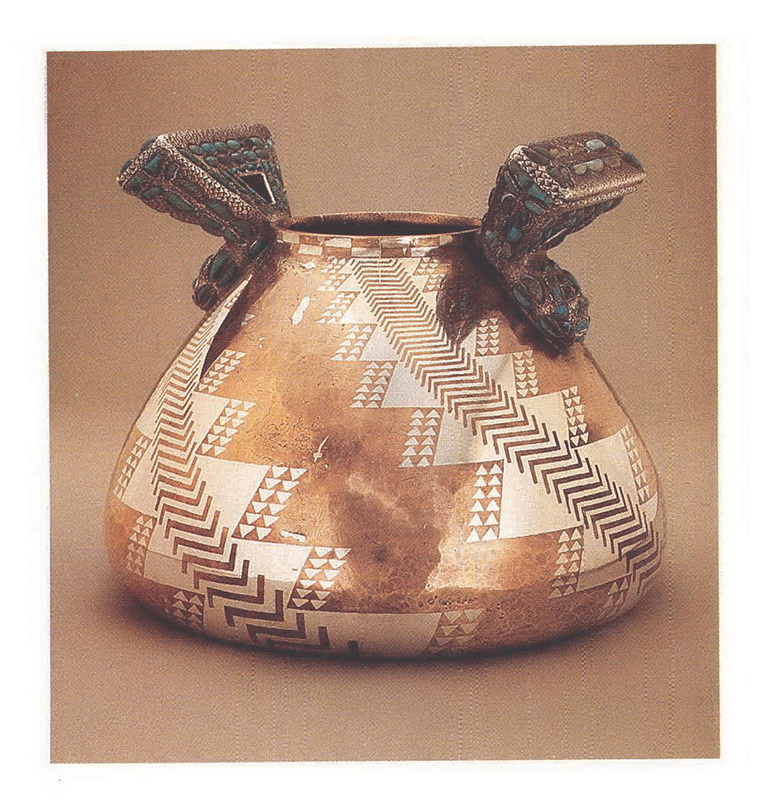

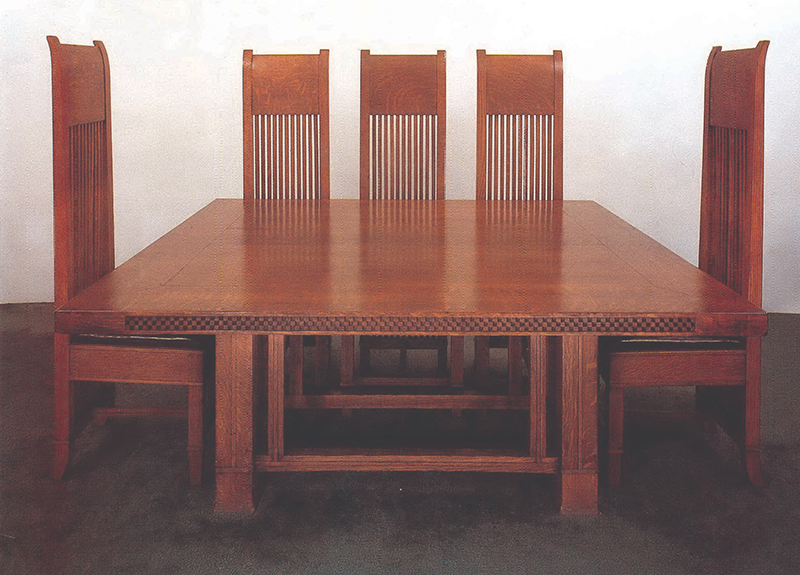

Frank Lloyd Wright and the Prairie school, along with the associated designers of the arts and crafts movement, emphasized simplicity, structure, handcraftsmanship, and a rejection of most historical styles. When the past did serve as indirect inspiration, vernacular and indigenous styles, such as those from the Orient or those of the American Indians, were called upon. The latter influence is obvious in the bowl shown in Plate IV, both in the shape and the decoration. The dining–room set by Frank Lloyd Wright shown in Plate V demonstrates the relatively spare ornamentation of American arts and crafts furniture compared to its European counterpart. When pulled up to the table the chairs create an almost roomlike environment — evidence of Wright’s genius at creating spaces.

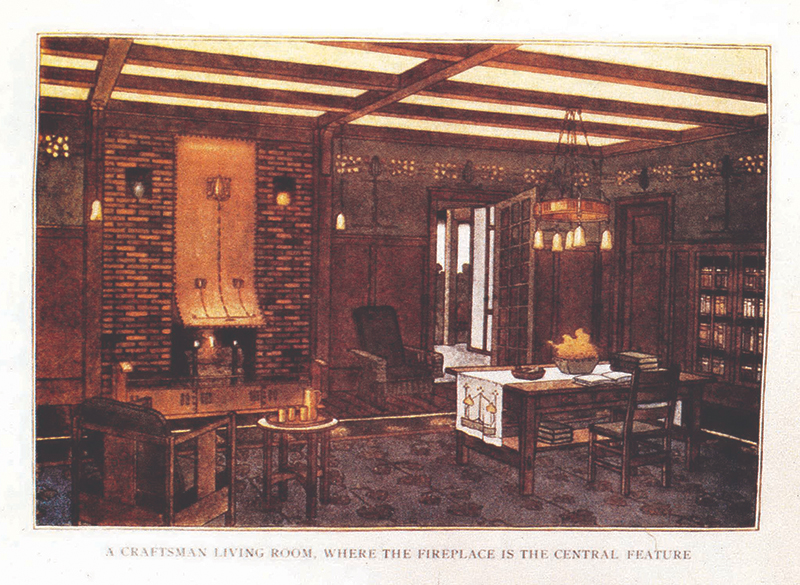

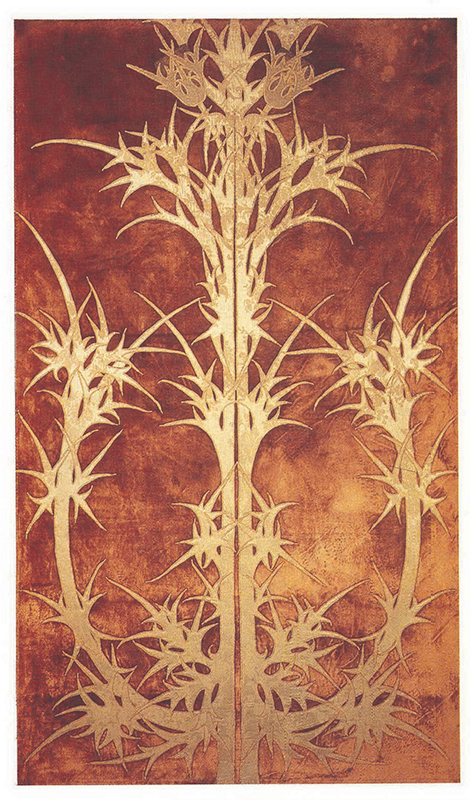

Despite their differences, one important correspondence between the designers of the American Renaissance and those of the arts and crafts movement was their desire for aesthetically unified interiors. This concept had evolved to a sophisticated level in Britain in the works of such arts and crafts designers as William Morris (1834 – 1896), who, in 1861, founded a company in London that produced and sold furniture, fabrics, wallpaper, and metalwork. In the United States the idea of an aesthetically unified environment was integral to the American Renaissance beginning in the 1870’s and 1880’s, and it was carried into the twentieth century by Wharton and Codman. It was fostered by the establishment of many interior design firms, particularly after the turn of the century. At the same time American arts and crafts designers began to produce a large range of furniture, fabrics, and other objects which could be used to create the kinds of complete interiors depicted in the pages of Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman magazine, which was the chief organ of the arts and crafts movement in this country (see Pl. I). George Maher’s fireplace surround (Pl. II) and portiere (Pl. Ill) are magnificent examples of the designer’s desire to realize such interiors. Both designs are based on plant forms which, with their linearity and compositional clarity, identify them as the work of one hand.

By World War I the arts and crafts movement had largely died in America, while between 1915 and 1930 the number of popular revival styles increased. The most fashionable were the American colonial, English Tudor, Mediterranean, French Norman, and Spanish. Period rooms were created at the major museums in the country, and in 1924 the American Wing opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. These rooms reacquainted the public with American period styles and perpetuated their popularity.

By the end of the 1920’s art deco furniture and modernist designs captured the interest of museums and the public, and in 1926 the Metropolitan opened permanent galleries of modern decorative art. Art deco and modernist furniture never sold as well as furniture in period styles, yet the public came in droves to see it. When the Metropolitan opened its exhibition The Architect and the Industrial Arts in 1929 ten thousand people3 came the first Sunday, and the show was extended from six weeks to six months. The exhibition included entire rooms designed by Eliel Saarinen, Ely Jacques Kahn, Ralph T. Walker, Joseph Urban, Eugene Schoen, John Wellborn Root, Raymond M. Hood, and Armistead Fitzhugh. R. H. Macy’s 1928 International Exposition of Art in Industry attracted one hundred thousand visitors eager to view its modernist products during its first week.4

The section of the Whitney Museum exhibition and catalogue that treats the period between 1915 and 1930 may seem problematic for some because of the inclusion of American colonial revival furniture. By the 1920’s the colonial revival had gone through several phases, and although still very popular could hardly be said to be high style any longer. It offered little in the way of innovation except in the uses the furniture was put to—a Chippendale style high chest of drawers used to house a radio, for example. It may be questioned if this object can truly be considered innovative alongside the wonderful adjustable table made by Donald Deskey shown in Figure 3.

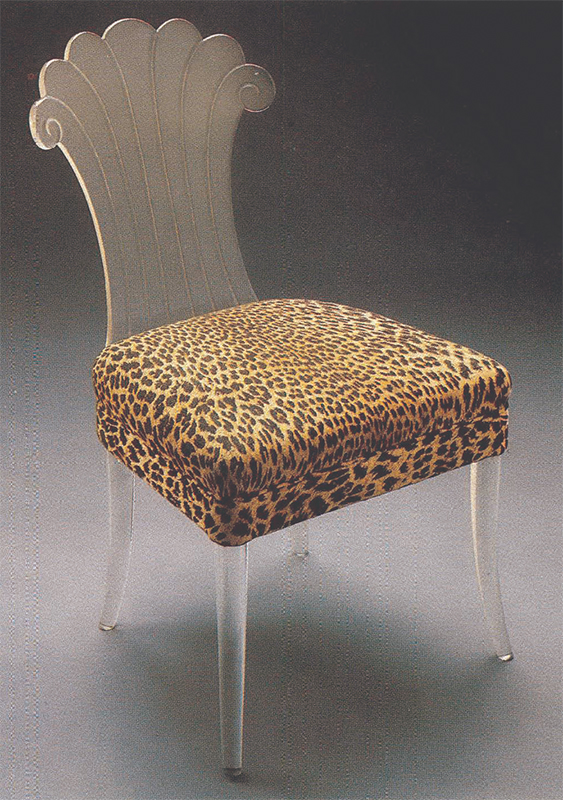

To be high style, revival furniture must offer an innovative aesthetic interpretation of its model. Eighteenth-century English furniture designed by the Adam brothers, for example, manipulated classical elements to produce a creative look at the past, while George Steedman’s outdoor furniture of about 1930 (see Fig. 4) combined elements of Spanish furniture with new materials to produce a forward-looking object which expanded the range of design possibilities. Many designers of the 1930’s and 1940’s were directly inspired by classical Greek and Roman forms and other ancient styles, but they interpreted them in new and abstract ways. Terence H. Robsjohn-Gibbings so used Egyptian motifs in the table illustrated in Plate VI, while Elsie de Wolfe’s upholstered Lucite chair of about 1939 (PL VIII) is a witty reinterpretation of the Biedermeier style.

By the late 1930’s Americans began to become more influential in international design circles, and they have remained so in the post–World–War–II period. Particularly significant in this regard was the streamlined moderne style of the 1930’s perfected by a new breed of design professional, the industrial designer. Streamlined moderne was originally a European style but Americans developed its possibilities, since even during the Depression there was a greater market here than in Europe for mass–produced objects, trains, appliances, and the like. The style is characterized by sharp curves, smooth surfaces, and the frequent use of parallel lines as a decorative motif (see Pl. VII), all of which underscored machine production and created an image of fast–paced modern life. Streamlined moderne was seen by many as a way of promoting optimism and increasing sales through its image of industrial power. Perhaps because of this symbolism and because it was used for so many useful objects, streamlined moderne became a high style that was accepted not just by intellectuals and the rich but by almost everyone.

The pluralism in American aesthetics during the 1920’s and early 1930’s created a debate among critics of architecture and design between those who defended modernism and those who remained traditionalists. Many American architects of the period chose a historical style from those most fashionable at the time, while others chose the non–historical art deco in the late 1920’s and modernism and streamlined moderne in the 1930’s.

Some critics took issue with the eclecticism of the period, among them Lewis Mumford who wrote in American Taste of 1929:

I doubt if any period has ever exhibited so much spurious taste as the present one; that is, so much taste derived from hearsay, from imitation, and from the desire to make it appear that mechanical industry has no part in our lives and that we are all blessed with heirlooms testifying to a long and prosperous ancestry in the old world….. The last touch of absurdity to this hunt for antiques was given in a government bulletin which suggested that every American house should have at least one “Early American’’ room.5

Others, such as the talented architect Paul Cret (1876–1945), who designed many buildings in a freely eclectic manner using classical and Renaissance sources to create a new and abstract style, defended the innovative eclecticism as modern. He wrote in 1933:

Above all we must no more be hypnotized by the desire to be original than by the complex to be archaeologically correct. We must be ourselves. If the conception of a work, the study of its expression in forms and decoration is your own, and not a dull copy, you need not be concerned about being modern—you cannot be anything else.6

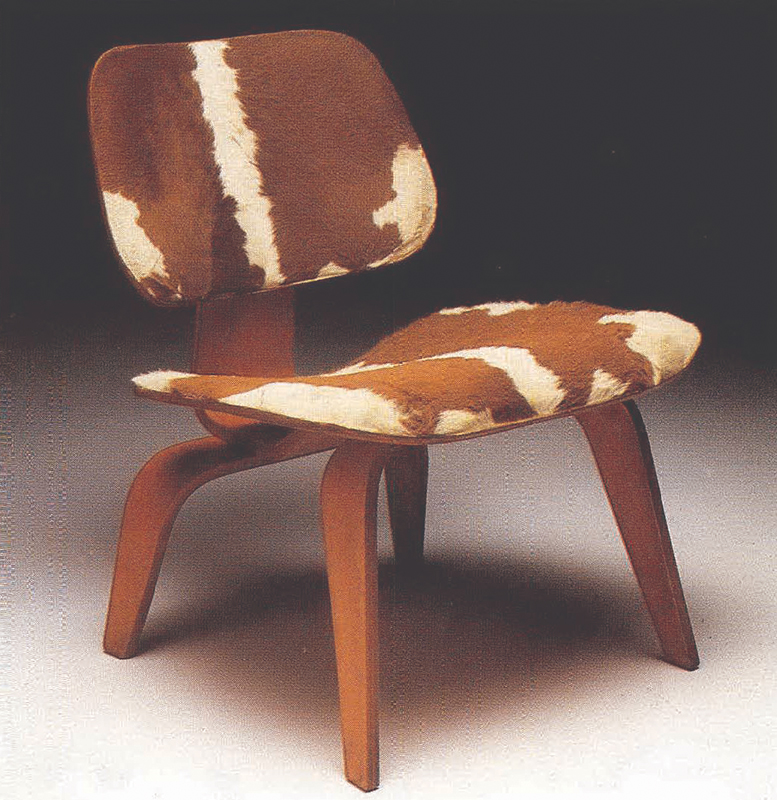

In the I930’s many new materials were introduced to industrial and furniture designers—new metals, Celluloid, Bakelite, Catalin, Plexiglas, and Lucite— which changed the look of furniture and other objects. Distinctive also was a turn away from the emphasis on the machine aesthetic to a less severe style sometimes inspired by natural forms. Rosemarie Bletter, in her excellent essay on the years 1930–1945 in the Whitney’s exhibition catalogue, shows that as early as 1932 Russel Wright (1904–1976) initiated this mode by creating an armchair in which the shape of the arms reflects the curves and joints of human hands and wrists. We generally associate free–form tables with the 1940’s and 1950’s, but Frederick Kiesler (1890–1965) created such objects as early as 1935. Charles Eames, too, was influenced by the new aesthetic, new materials, and mass production, and in the mid–1940’s created now-classic plywood chairs with compound curves which accommodate the human body (see Pl. IX).

After World War II there was increased interest in mass production and new industrial solutions to design problems. But again the world of high–style design provided choices of approach. Charles and Ray Eames’s metal and upholstered furniture and their plywood chairs emphasize materials and structure, while in Eero Saarinen’s (1910–1961) softer brand of modernism the emphasis was on shape not structure. His tulip pedestal chair of 1956, for example, is composed of cast aluminum and plastic, but it presents a unified profile because the whole is a single color.

There has been a continued involvement with modernism in the 1980’s as well as a fascination with both recent and more distant history. The furniture of the Vienna Secession, the art deco style, the American and English arts and crafts movements, and the furniture and architecture of the eighteenth century are all influential today. Two chairs made in 1984, one by Robert Venturi (Pl. X) and the other by Ward Bennett (Fig. 5) accurately reflect the present use of the past.

Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), one of the great American books on architecture, was the most important break by a post-war theorist with a canonical acceptance of the international style and its rejection of history. Venturi’s statement that the buildings of the Renaissance and other architecture of the past have much to teach us was seen as radical at the time. There is no question that this book influenced an entire generation of architects, and perhaps clients, to pick up history books again and to learn how to design ornament as well as traditionally shaped rooms.

In his architecture and in his writing Venturi has always combined irony with an interest in American design icons—for example, the shingle-style house and the highway strip. In his wood and plastic–laminate chair these qualities create a commentary on a style that has nostalgic overtones for Americans. Painted in an overall pattern reminiscent of Jasper Johns’s cross-hatched canvases, this evocation of Chippendale is emphatically flattened so that the chair becomes almost a stage prop. As a prop it is a witty comment on the historical revivalism in architecture today and on our romantic view of our eighteenth-century past.

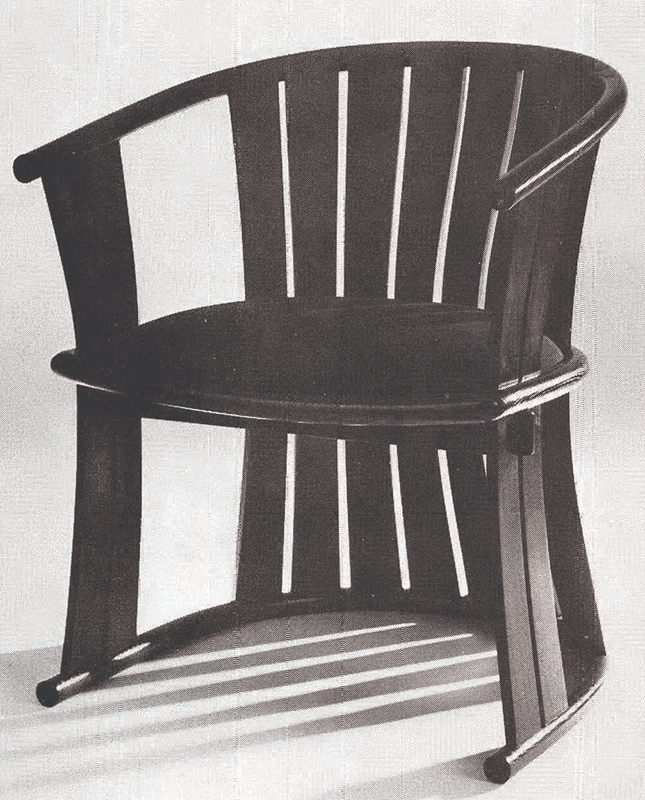

Ward Bennett’s wooden stave chair (Fig. 5) with an upholstered seat is allied to another American design tradition, one that is particularly strong in architecture. This tradition emphasizes structure and vernacular building. Bennett has worked for many years with the tub–chair shape as one responsive to human anatomy, but this chair is different. Instead of a solid back and traditional legs the chair is composed of continuous staves, each of a slightly different curvature, secured by the rim of the seat. In construction the chair is reminiscent of wooden barrels and traditional wooden rowboats. A strengthening crosspiece extends beyond the staves, where it is secured by dowels. This recalls a similar element in the arts and crafts architecture of Charles Sumner (1868–1957) and Henry Mather (1870–1954) Greene. The Greenes derived this device from Japanese architecture and like Bennett were interested in Oriental design. The forward tilt and curve of the back rail and arms are almost imperceptibly inspired by Chinese chairs. Bennett’s chair is an important example of the way past traditions may subtly influence what appears to be an uncompromisingly modern chair.

The Whitney Museum’s exhibition situates American decorative arts and industrial design within the design traditions of the West. The objects chosen tangibly illustrate that our connection with European design has been creative, not dependent. By modifying inspiration from abroad we have created an American dialect within the larger context of twentieth-century design. At times we have been more heavily influenced by Europe than at other times, such as during the Depression and after World War II, when we have led the way. This exhibition and catalogue not only reveal our innovative contributions to Western design but also the pluralism of vision within American high styles, thus allowing us to see the past more as it really happened than as myth.

Except for the illustration in Plate I and the portiere in Plate III, the objects illustrated in this article are on view in the exhibition High Styles: Twentieth–Century American Design, on view at the Whitney Museum until January 5, 1986.

1Lisa Phillips, “Introduction,” High Styles: Twentieth-Century American Design (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, 1985), p. ix. Phillips, who is associate curator and head of the branch museums of the Whitney Museum, directed the exhibition and contributed to the catalogue. Rosemarie Haag Bletter, Martin Filler, David Gebhard, David A. Hanks, and Esther McCoy were guest curators for the show and also wrote essays for the catalogue. Nancy Princenthal was the exhibition coordinator. 2They wrote, “Tout ce que n ’est pas necessaire est nuisible. . . Modern civilization has been called a varnished barbarism: a definition that might well be applied to the superficial graces of much modern decoration. Only a return to architectural principles can raise the decoration of houses to the level of the past” (The Decoration of Houses [1902 ed., reprinted New York, 1978], p. 198). 3Cervin Robinson and Rosemarie Haag Bletter, Skyscraper Style: Art Deco New York (New York, 1975), p. 48. 4Karen Davies, At Home in Manhattan: Modern Decorative Arts, 1925 to the Depression (Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, 1983), p. 84. 5San Francisco, California, 1929, p. 21. 6“Ten Years of Modernism,” Federal Architect, no. 4 (July 1933), p. 12. For further discussion of the debate between traditional and non–traditional architects, see Deborah Nevins, Between Traditions and Modernism (National Academy of Design, New York, 1978).

DEBORAH NEVINS is an adjunct assistant professor in the department of architecture at Barnard College in New York City.