In the summer of 1920, Robert Frost moved from Franconia, New Hampshire, to the village of South Shaftsbury in Bennington County, Vermont, where he lived from 1920 to 1938. For the subtitle to the second volume of his Frost biography, Lawrance Thompson aptly styled the period from 1915 to 1938 as the poet’s “Years of Triumph.” Frost had little-to-no name recognition on his return to America in 1915 after a three-year stint in England, but by the time he arrived in South Shaftsbury just five years later he was already widely recognized as one of America’s greatest living poets. During the early decades of the twentieth century, southwestern Vermont—close enough to major urban centers, such as Boston and New York, that one could jump on a train or in a car and be there in just a few hours—became a sort of mecca for cultural figures seeking the respite of rural life. Vermont became a retreat where Frost could write, and connect with nature, family, and a circle of friends that included many other talented artists and writers.

While living in South Shaftsbury Frost wrote many of his most famous poems—notably “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening,” which he called his “best bid for remembrance”1 and is still one of America’s most anthologized poems—and won three of his four Pulitzer Prizes. Frost’s poems still resonate today. In plain, precise, yet musical language, frequently laced with dry wit, they combine keen observation of the natural world with deep, and sometimes dark, reckonings on the human condition.

Frost was inspired by the local landscape—the apple trees he planted, the stone walls he admired, and the fields, forests, lakes, streams, and mountains that surrounded Shaftsbury. The region’s cultural and human networks proved no less stimulating. Amongst his circle of friends and colleagues were the visual artists Charles Burchfield, Rockwell Kent, J. J. Lankes, Luigi Lucioni, and Clara Sipprell. During his later years, Frost’s admirers included such artists as Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth. The latter noted that “Mr. Frost’s clarity of vision has been a very real challenge and inspiration to me in my work.”2 In discussing Wyeth’s work in relation to Frost’s poetry, scholar Nancy Anderson notes, “A keen observer of the natural world, he used exterior prompts for interior purposes– looking out triggered looking in.”3 This concept of using “exterior prompts for interior purposes” seems an apt metaphor for a consideration of Frost’s work in relation to the artists he was associated with during his South Shaftsbury years as well. Like Frost’s poetry, the works of Burchfield, Kent, Lankes, Lucioni, and Sipprell take a clear-eyed look at the outer worlds as a means of exploring internal atmospheres and the human condition.

Some Exhibition Highlights:

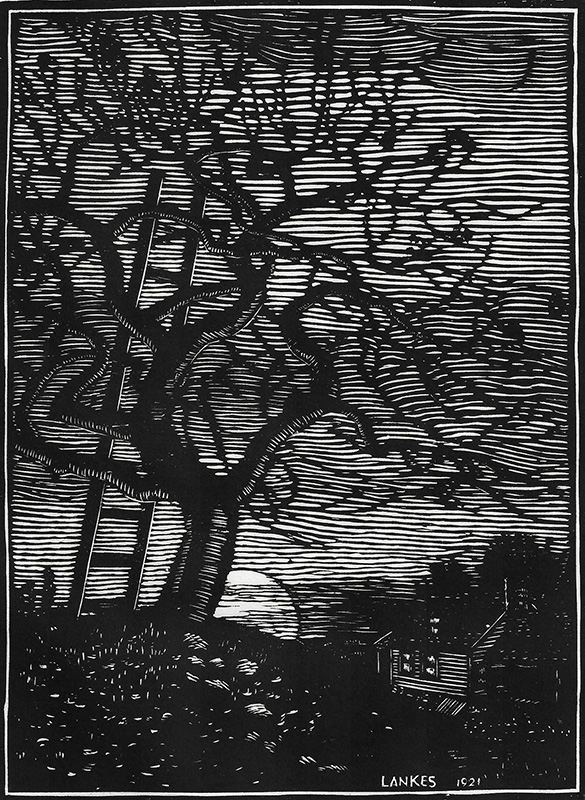

October (Moonlight and Appletree), 1921

Julius John Lankes

“My long two-pointed ladder’s sticking through a tree/ Toward heaven still,/…But I am done with apple-picking now./ Essence of winter sleep is on the night,/…I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend./…For I have had too much/ Of apple-picking: I am overtired/ Of the great harvest I myself desired.”

— from “After Apple-Picking” by Frost4

J. J. Lankes’s woodcuts are inextricably linked with Robert Frost’s poetry during the poet’s time in South Shaftsbury, illustrating two of his published collections from this period, New Hampshire (1923) and West- Running Brook (1928), in addition to a number of other collaborative efforts. The collaborations and close friendship between the two men began in earnest in 1923. Frost noted they shared a “coincidence of taste,”5 admiring each other’s work before ever having met. October (Moonlight and Appletree) was one of Lankes’s first attempts to capture the essence of Frost’s poetry pictorially. Lankes wrote in his first letter to Frost, “O, I fell for your work as soon as I saw it. It happened that I was trying to get just such a quality in my work.”6 Created in July 1921, Lankes’s print echoes and emphasizes a number of the key motifs in Frost’s poem: an abandoned “two-pointed ladder” extends through the gnarled, leafless branches of an apple tree, and the moon is beginning to rise above the horizon, indicating the end of a long day.

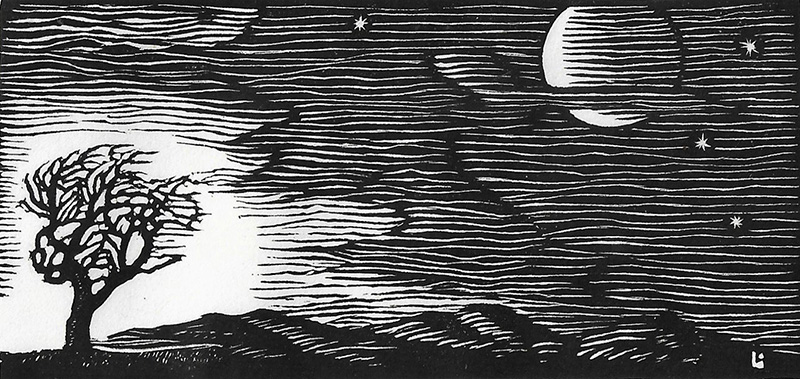

Star-Splitter — Dawn, 1927

Lankes

“He burned his house down for the fire insurance/ And spent the proceeds on a telescope/ To satisfy a life-long curiosity/ About our place among the infinities”

— from “The Star-Splitter” by Frost

This is a variant of a woodcut Lankes created as the tailpiece for Frost’s “The Star-Splitter,” when it was published, along with four other Lankes images, in the September 1923 issue of Century magazine. The magazine was known for working with leading artists to illustrate its literary content. On his drive from Vermont to New York to meet with Century’s editor, Carl Van Doren, in early January 1923 to select an illustrator, Frost had given a reading at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts. Following the reading, his host, Loring Holmes Dodd, shared his extraillustrated copies of the poet’s North of Boston (1914) and Mountain Interval (1916), into which he had inserted a selection of woodcuts by Lankes that he felt “fitted the poems as though drawn for them.”7 It was out of this serendipitous encounter that Frost and Lankes’s long-lasting collaborative friendship was born.

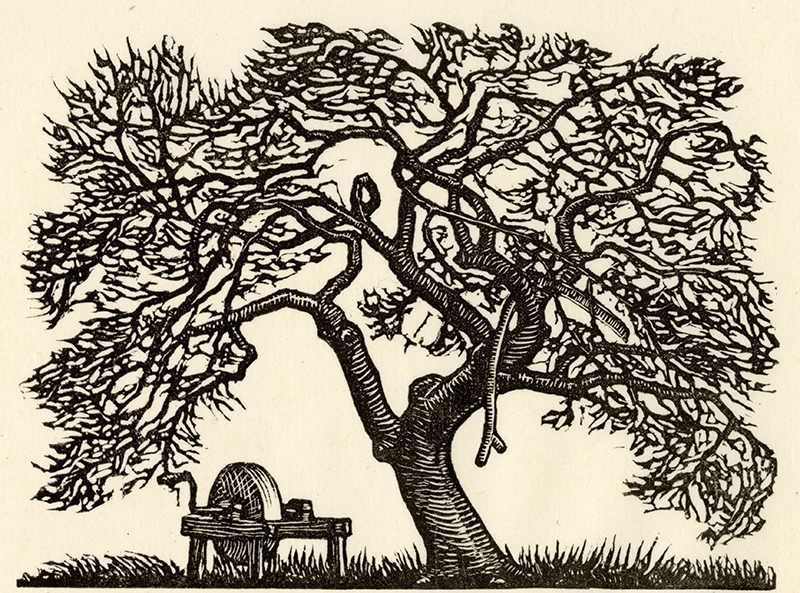

Apple Tree and Grindstone (tailpiece in New Hampshire), 1923

Lankes

“Having a wheel and four legs of its own/ Has never availed the cumbersome grindstone/ To get it anywhere that I can see/…It stands beside the same old apple tree/…A Father-Time-like man got on and rode,/ Armed with a scythe and spectacles that glowed.”

— from “The Grindstone” by Frost

Frost was so pleased with the woodcuts Lankes created for “The Star-Splitter” that he invited him to illustrate his soon-to-be published book, New Hampshire. The commission was rushed by Lankes’s standards— he got the job in August 1923 and sent off his four woodcuts (see Fig. 1) just three weeks later, since the book was set to be published in October. Initially neither the artist nor the poet was wholly pleased with the final product. By the end of the year, after having received much positive feedback, Frost wrote to Lankes, “I’m proud of having thought of you for the book. People have all spoken of your part in it. We won’t attempt to divide the honors, however, separating yours from mine. We’ll hold them in common like true communists of the Golden Age.”8

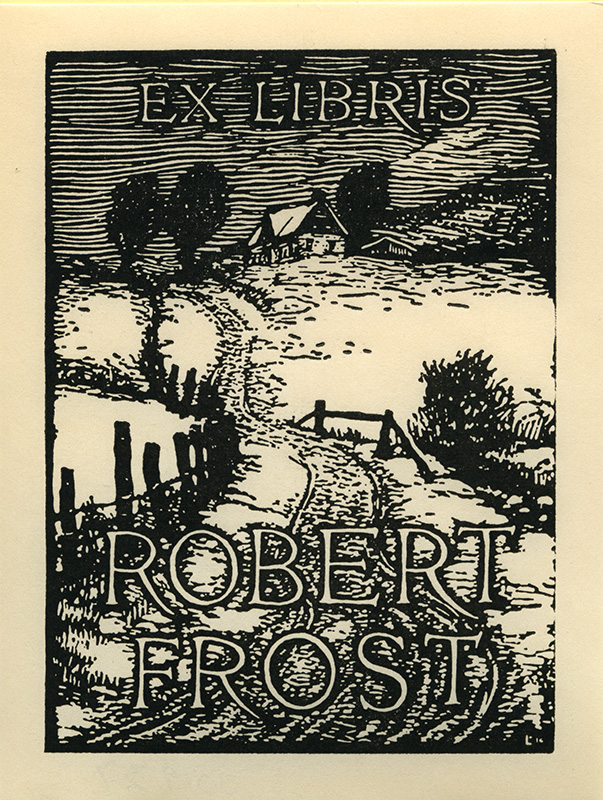

Robert Frost bookplate, 1923

Lankes

Lankes designed this bookplate as a gift to Frost in the afterglow of the publication of New Hampshire. He based the image on some photographs of the stone Peleg Cole house, Frost’s first home in Vermont, a sturdy Dutch-style colonial era structure, built in 1769 of locally quarried stone and native timber, which the best-selling author Dorothy Canfield Fisher had helped him find. The photos had been sent to Lankes by a mutual friend of his and Frost’s, Edward Phelps “Ned” Jennings, a print collector and sometimes dealer with deep familial ties to nearby North Bennington.

Puritan Church, 1923–1927

Rockwell Kent

“The graveyard draws the living still,/ But never any more the dead/…So sure of death the marbles rhyme,/ Yet can’t help marking all the time/ How no one dead will seem to come./ What is it men are shrinking from?” — from “The Disused Graveyard”

— by Frost Rockwell

Kent moved to an idyllic farm on the slopes of Red Mountain in Arlington, Vermont, in 1919, and lived there until 1925. Like Frost, Kent moved to Bennington County at the urging of Dorothy Canfield Fisher. Though they were not close friends, Frost and Kent knew each other through a network of mutual friends and were well acquainted with one another’s work. The work Kent created while living just fourteen miles north of the Frosts’ farm echoes some of the themes and moods in Frost’s poems, notably their shared interest in mortality.

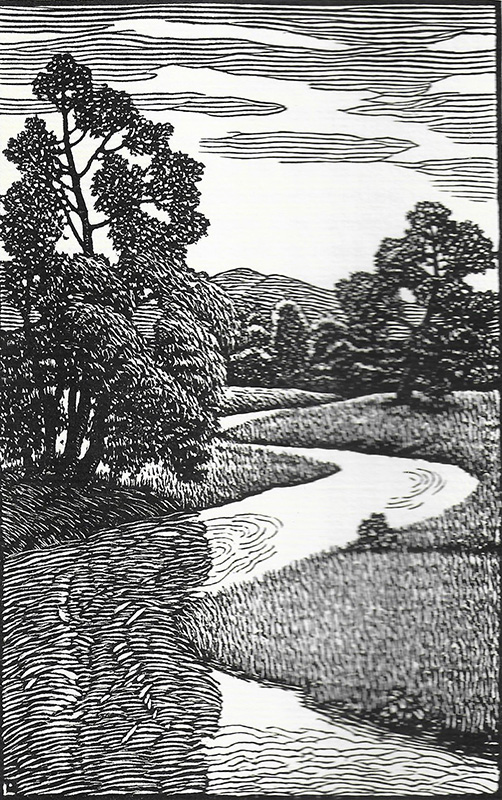

West-Running Brook, III, 1928

Lankes

In 1925 Lankes and his wife moved from Buffalo, New York, to Tidewater Virginia, but he and Frost continued a warm correspondence. In 1928 they collaborated once again when, at the poet’s invitation, Lankes created four woodcuts for Frost’s new book, West-Running Brook. The artist made sure Frost sent him the texts of the poems well in advance of the deadline, giving him more time to work up the images, which met with consistent praise. Including a limited edition of one thousand copies featuring woodcuts hand-printed and signed by Lankes, he ended up printing nearly five thousand impressions for the project. Though the book was the only major publication during Frost’s South Shaftsbury years to not win a Pulitzer, West-Running Brook was a popular success. The poet used the proceeds to purchase a new farm, The Gulley, which Lankes visited in the summer of 1929, helping the Frosts to fix it up.

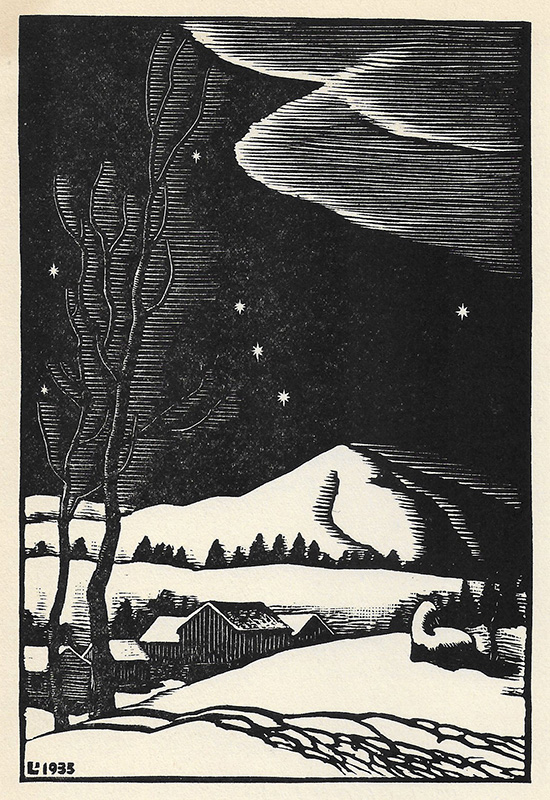

Winter Night II, 1933

Lankes

“I saw reality the other night,/ By New England moon-light./ All of my life, living had been/ One or another kind of dream./ Now, nothing festooned itself between/ Me and the substance of moon-beam.”

— from Remembering Vaughan in New England by Genevieve Taggard (1894–1948)9

Lankes’s Winter Night II, based on a sketch of Bennington’s Mount Anthony from Frost’s farm, illustrated Genevieve Taggard’s poem Remembering Vaughan in New England when it was published as a chapbook in 1933. Frost was famously conservative when it came to politics. Given this, it may come as a bit of a surprise that many of his closest friends were committed leftists. Taggard was a poet, critic, and activist, heavily involved with the socialist cultural scene in New York City in the 1920s. Despite their political differences, Frost enthusiastically recommended Taggard to Robert Devore Leigh, Bennington College’s first president, in early 1932, and she was later described by her former colleague and college historian Tom Brockway as “the exuberant star”10 of the school’s fledging literature department.

Green Mountains, Vermont, 1923–1927

Kent

“She runs from tree to tree where lie and sweeten/ The windfalls spiked with stubble and worm-eaten./ She leaves them bitten when she has to fly./ She bellows on a knoll against the sky.”

– from “The Cow in Apple Time” by Frost

With their heads turned away from the viewer, the cows in this painting seem to be contemplating the sublime view from a vantage point near Kent’s studio in Arlington. Or perhaps they are just “bellow[ing] on a knoll against the sky,” as Frost puts it in his comical bacchanalian poem.

The Glory of Spring, 1934–1955

Charles Burchfield

“These pools that, though in forests, still reflect/ The total sky almost without defect,/ And like the flowers beside them, chill and shiver,/ Will like the flowers beside them soon be gone,/ And yet not out by any brook or river,/ But up by roots to bring dark foliage on.”

— from “Spring Pools” by Frost

Considered one of the great modern American painters, Charles Burchfield moved to Buffalo, New York, in 1921, where he lived and worked for the rest of his life. There he befriended J. J. Lankes, with whom, in August 1924, he and another artist friend, William J. Schwanekamp, visited the Frosts at their stone house. Burchfield’s paintings often suggest the transcendent, spiritual power of nature in relation to humankind in ways that recall Frost’s treatment of the theme. In fact, Burchfield’s journal entry from his visit to Frost that August notes that one of the topics of discussion that evening was “spiritualism.” Burchfield, who was an avid writer and a reader of contemporary American literature, said of his own work: “My things are poems—(I hope).”11

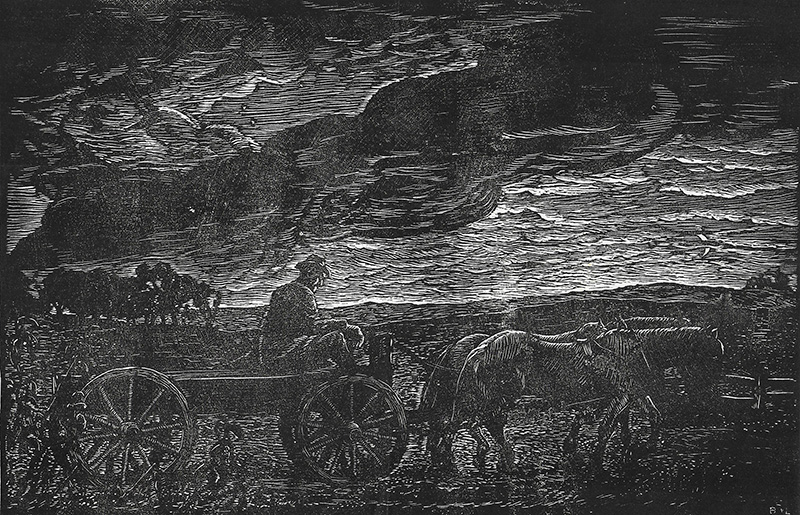

Nightfall, c. 1923–1925

Burchfield and Lankes

During the mid-1920s Lankes collaborated with Burchfield on a number of woodcuts. Burchfield drew his designs directly on the block and Lankes cut and printed them. The subjects of many of their collaborative woodcuts, such as this tired farmer driving his horse and wagon, recall figures and settings in Frost’s narrative poems, while others deal with the tumultuousness of nature and the heavens, themes also popular with the poet.

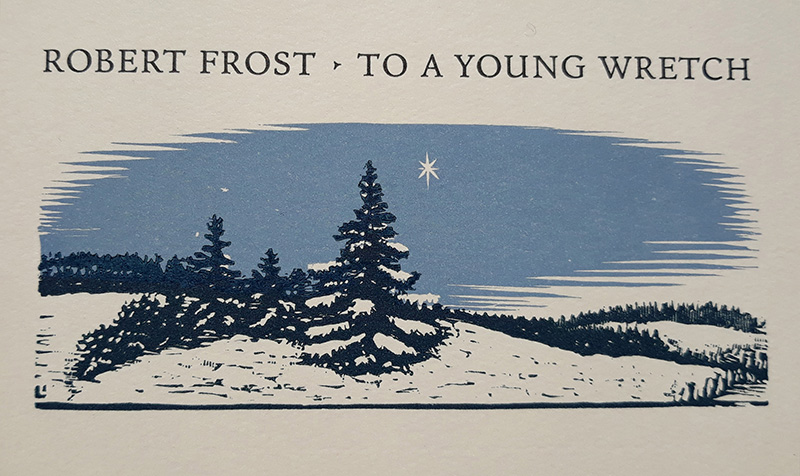

To A Young Wretch, 1937

Frost poem with two-color woodcut by Lankes

“And though in tinsel chain and popcorn rope/ My tree, a captive in your window bay,/ Has lost its footing on my mountain slope/ And lost the stars of heaven, may, oh, may/ The symbol star it lifts against your ceiling/ Help me accept its fate with Christmas feeling.”

— from “To a Young Wretch” by Frost

In December 1936 two South Shaftsbury youths (Fred Hoyt, age nine, and Chuck Downing, age six) cut down a Christmas tree on land belonging to Frost. The poet was away, but the boys were seen dragging the tree homeward by Constable Floyd Holiday, who was also the caretaker of Frost’s property. The boys got a talking to, and, when he heard about the incident, Frost wrote a poem, the playful and conflicted “To a Young Wretch.” Frost used the poem as his Christmas “card” the following year, and included it in his book A Witness Tree, published in 1942. Frost created Christmas “cards” like this nearly every year from 1934 to 1962, a collaboration between the poet and printer Joe Blumenthal at the Spiral Press.

The Birches, 1940 Luigi Lucioni

“It’s when I’m weary of considerations,/…I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,/ And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk/ Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,/ But dipped its top and set me down again./ That would be good both going and coming back./ One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.”

— from “Birches” by Frost

“I bought a farm for myself for Christmas. One hundred and fifty three acres in all, fifty in woods…There is a small grove of white paper birches doubling daylight. The woods are a little too far from the house. I must bring them nearer by the power of music like Amphion or Orpheus…You must see us together, the trees dancing obedience to the poet (so called).”

– Frost to Louis Untermeyer, January 6, 192912

Luigi Lucioni was one of America’s most beloved painters in the 1930s, and in 1932 at age thirty-one became the youngest living artist to have a work acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. That sale, in turn, led to a commission from Electra Havemeyer Webb, founder of the Shelburne Museum, and Lucioni’s lifelong connection to Vermont as a visitor and resident. There is little evidence that Lucioni and Frost ever met or interacted directly. However, they both inscribed their names on a signature quilt, now in the Bennington Museum collection, compiled by Lady Beatrice Gosford, documenting the many artists, writers, and politicians who comprised the social circle at her eighteenth-century tavern home in Shaftsbury during the 1930s and 1940s. More significantly, the themes and moods of their work often resonate, especially the “clarity of vision” Andrew Wyeth admired in Frost’s work, and their love for southwestern Vermont’s paper birches.

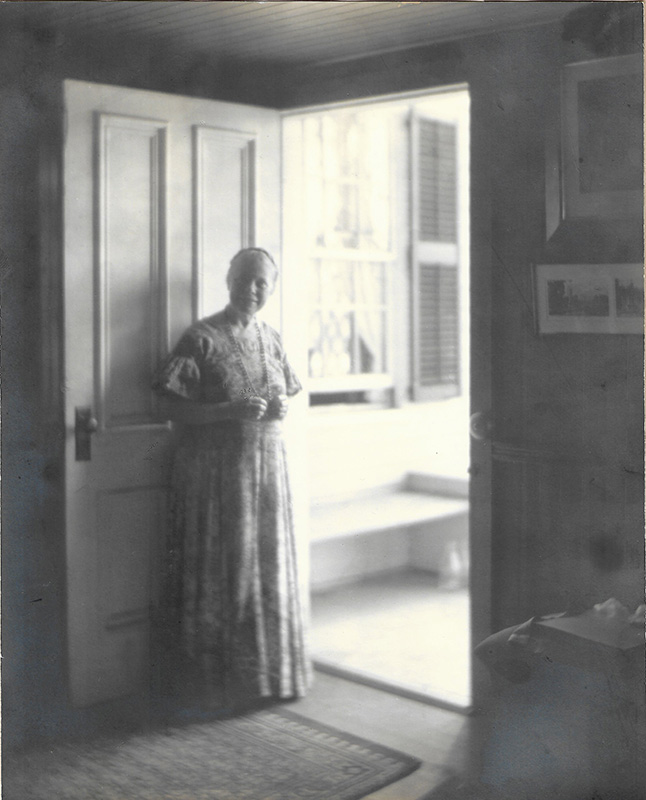

Sarah Cleghorn, 1940

Clara Sipprell

“The golf links lie so near the mill/ That almost everyday/ The laboring children can look out/ And see the men at play.”

– “The Golf Links Lie So Near the Mill” by Sarah Cleghorn13

Clara Sipprell was a leading pictoralist photographer of the mid-twentieth century, best known for her naturally lit, atmospheric portraits of some of America’s leading cultural figures. She learned photography in her brothers’ studio in Buffalo, New York, summered in Thetford, Vermont, beginning around 1915, and moved to Manchester, Vermont, full-time in 1937, at the urging of Frost, whom she photographed extensively. Her subject here, Sarah Cleghorn, a nearly lifelong resident of Manchester, was a politically progressive writer/poet, whose famous poem “The Golf Links Lie So Near the Mill” decries child labor. Some of her poems in a different register, exploring the landscape, flora, and fauna of Vermont, were interspersed with Dorothy Canfield Fisher’s short stories in Canfield Fisher’s book Hillsboro People (1915). Frost referred to Cleghorn, Canfield Fisher, and Zephine Humphrey as the “three great ladies” in his introduction to Cleghorn’s 1936 autobiography, Threescore (1936). As a member of the board of the Poetry Society of Southern Vermont, she brought Frost to the area for a reading in 1919, sparking his move there the next year.

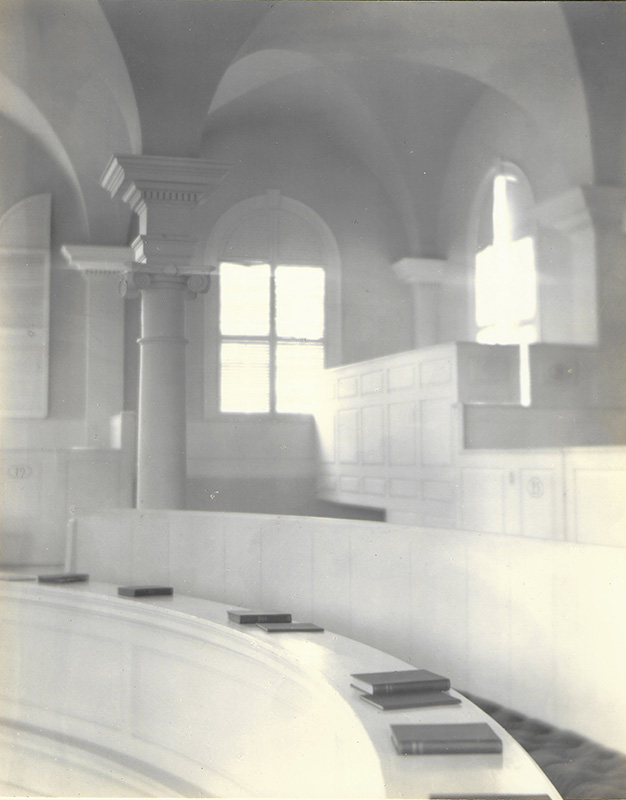

Choir of the Old First Church, c. 1937

Sipprell

Bennington’s Old First Church, built 1804–1805, is considered one of the masterpieces of early nineteenth-century religious architecture in New England. In the post–Civil War period, the interior was badly renovated: the original box pews and high pulpit were removed and a stained-glass window added, destroying the original neoclassical design. In 1933 Frost added his name to a long list of Vermonters endorsing the restoration of the Old First Church. The Vermont legislature soon recognized the church, and the historic cemetery by which it is surrounded, as “Vermont’s Colonial Shrine”— thereby a state monument—and more than $30,000 was raised for the restoration, which took place between October 1936 and August 1937. At the dedication ceremony on Sunday, August 15, 1937, Frost was one of many dignitaries to speak from the newly restored pulpit, reading his poem “The Black Cottage.”

Robert Frost, “At Present in Vermont” is on view at the Bennington Museum to November 8.

1 Frost to Louis Untermeyer, c. May 2, 1923, in The Letters of Robert Frost: Volume 2, 1920–1928, ed. Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson, Robert Bernard Hass, Henry Atmore (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2016), p. 339. 2 Quoted in Nancy K. Anderson, “Wind from the Sea: Painting Truth beneath the Facts,” in Andrew Wyeth: Looking Out, Looking In (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2014), p. 25. A special thanks to Bonnie Clause, author of Edward Hopper in Vermont (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 2012), for bringing this and other references to Frost’s relationship with both Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth to my attention. 3 Anderson, “Wind from the Sea,” p. 27. 4 All Frost poem excerpts are taken from Robert Frost, Robert Frost: Collected Poems, Prose, and Plays (New York: Library of America, 1995). 5 Frost to Lankes, c. August 20, 1923, in The Letters of Robert Frost: Volume 2, p. 359. 6 Lankes to Frost, September 6, 1923, quoted in Welford Dunaway Taylor, Robert Frost and J.J. Lankes: Riders on Pegasus (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Library, 1996), p. 14. Taylor provides a full and detailed account of Frost’s and Lankes’s relationship and collaborations. 7 Ibid., p. 9. 8 Frost to Lankes, December 31, 1923, in The Letters of Robert Frost: Volume 2, p. 390. 9 Genevieve Taggard, Remembering Vaughan in New England (Rydal, PA: Arrow Editions, Rydal Press, 1933), p. 1. 10 Quoted in Phil Holland, “Robert Frost’s Association with Early Days of Bennington College,” Walloomsack Review, vol. 26 (Spring 2020), p. 20. Holland provides a thorough analysis of Frost’s involvement with the beginnings of Bennington College, including his relationship with Genevieve Taggard. 11 Charles Burchfield to Frank K. M. Rehn, October 2, 1940, quoted in John I. H. Baur, The Inlander: Life and Work of Charles Burchfield, 1893– 1967 (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press/New York: Cornwall Books, 1982), p. 152. 12 The Letters of Robert Frost: Volume 3, 1929–1936, ed. Donald Sheehy, Mark Richardson, Robert Bernard Hass, Henry Atmore (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021), pp. 33–34. 13 Sarah N. Cleghorn, Portraits and Protests (New York: Henry Holt, 1917), p. 75.

JAMIE FRANKLIN is the director of collections and exhibition at the Bennington Museum.