The story of Marcus and Co. is a dream script for a Julian Fellowes series. The New York jewelry firm is best known for creating exquisite art nouveau jewels that have been sought after by the American elite for more than a century.

Catering to the Rockefellers, Flaglers, Vanderbilts, Havemeyers, and Posts, with inventive designs and important gemstones, Marcus and Co. was one of the top American jewelry firms in the first half of the twentieth century.

The jewelry is exceptional, the clients elite, and the personal history of the family woven throughout is filled with romance, drama, death, and artistic triumph. It’s a perfect period soap opera, but even more fascinating because it all happened.

The new book, Marcus & Co.: Three Generations of New York Jewelers (Arnoldsche, $85), tells the story from Herman Marcus’s apprenticeship in Dresden, Germany, to the firm’s rise through New York society and its final location on Fifth Avenue. Authors Beth Carver Wees and Sheila Barron Smithie bring deep scholarship and a broad view to the book, weaving into the narrative the development and interconnectedness of the New York jewelry industry from the 1850s through the 1950s, and the changes brought by world events such as war and the Gold Rush. “It was important to us to tell the bigger picture of what was happening in New York at the time,” Wees says.

“The jewelers almost all started in Maiden Lane and kept moving up in the city. The final address was very close to where Cartier and Tiffany are today when they closed.” Wees and Smithie distinguish Marcus and Co.’s role as “an effective incubator for fledgling jewelers,” covering its relationship with a number of jewelers, among them T. B. Starr, F. W. Lawrence, and William Scheer, and larger firms such as Tiffany, Gorham, Lalique, and, notably, Raymond C. Yard, whose founder started out at Marcus and Co. as a door boy.

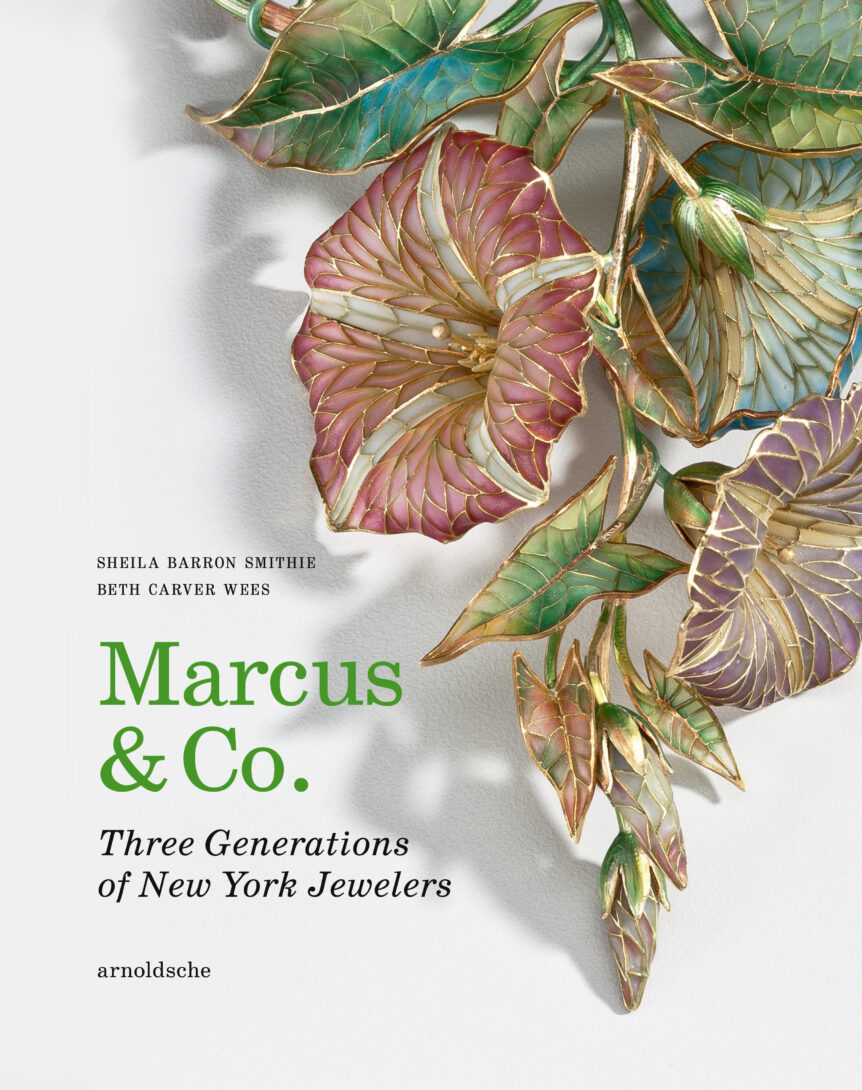

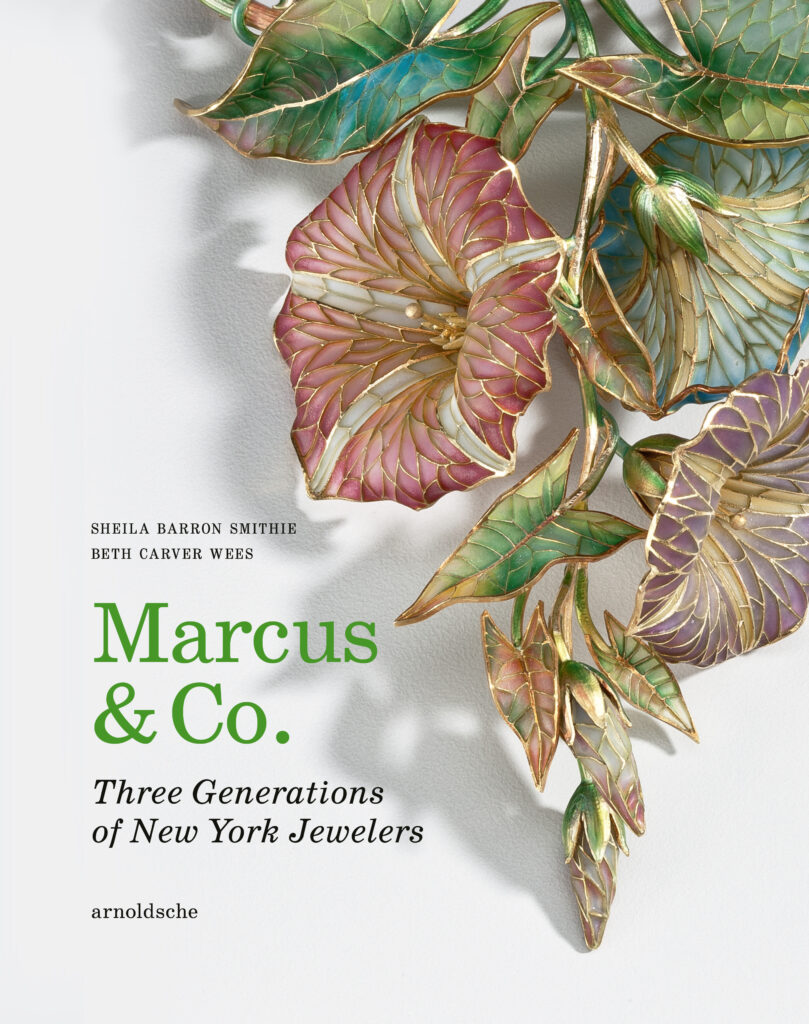

Wees references the plique-à-jour designs, elaborate enamel foliate pieces made by the firm in the early 1900s, as evidence that Marcus recognized the necessity of working with others. Open on both sides, like stained glass, these pieces are the pinnacle of Marcus’s output, and several are shown in the book (including on the cover). Wees says, “It took a whole village to create: a designer, goldsmith, silversmith, the plique, the stone setters to put everything together. It was all very specialized.”

The jewels are breathtaking. Whiplash curves, natural motifs, and bright colors are common threads. The Marcus family was heavily influenced by their frequent trips to India, where they bought stones, and by the art nouveau movement in Europe. In an 1882 pamphlet, Something About Neglected Gems, the firm wrote, “By the use of color, the work of the jeweler is raised to a fine art.” Wees says, “I always expect a piece of Marcus to be chased on the back, or otherwise beautifully finished.”

She adds: “The shanks on their rings were twisted or had diamonds on the back. Why? It didn’t need to be. They took that time to make it special.” Until now the most important sources on Marcus and Co. were two articles published in this magazine in 2007 by Janet Zapata, whom Wees and Smithie thank for getting “the ball rolling.” The authors significantly expanded the narrative by combing archives, fashion magazines, and financial records for mentions of the firm.

Luckily, several original drawing books survived and are heavily featured. Marcus & Co.: Three Generations of New York Jewelers has more than four hundred images, three hundred pages, and nearly as many footnotes. The book also includes a guide to marks and a section outlining how to decipher notations in the drawing books, creating an essential resource for future scholars.