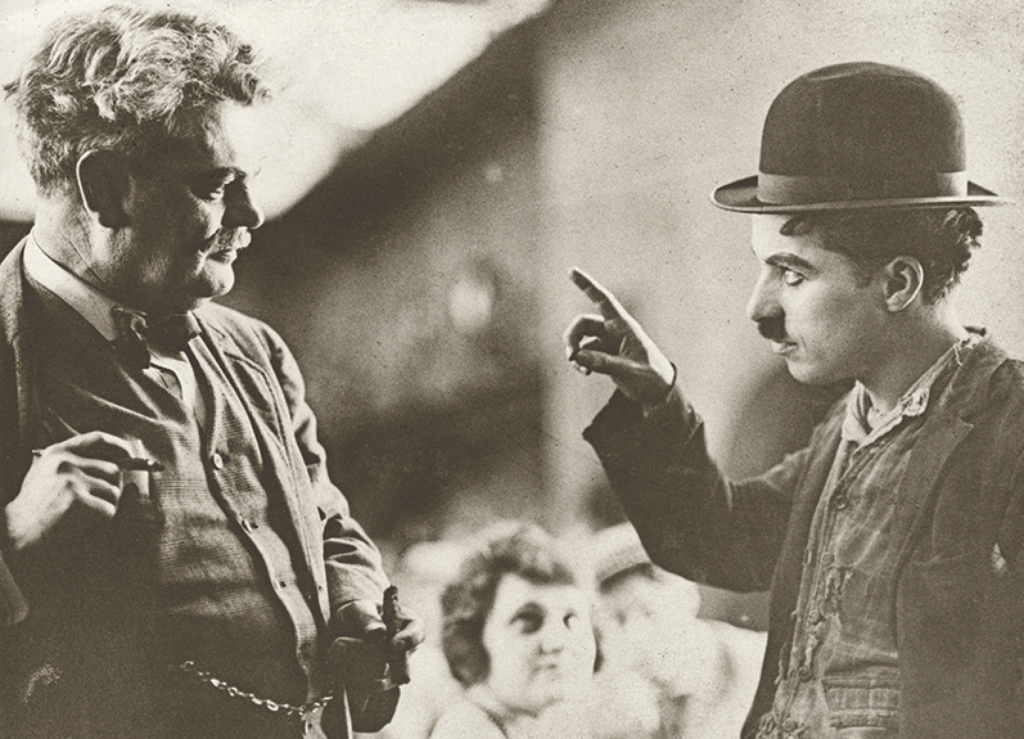

“Sometimes I think that he has . . . some great capacity for happiness in which we others are lacking,” Charlie Chaplin mused, considering the paintings of sunlit fields and flowers that made his artist friend Granville Redmond—with whom he pantomimed in such classics as A Dog’s Life and The Kid—one of the best-known of the California impressionists. Redmond himself appears pleasantly Falstaffian in a publicity photo with Chaplin from about 1918: plump and paunchy, with a thick mustache and a shock of surprisingly lush white hair, he clutches a cigar to his foppish tweed waistcoat and gazes wryly at his hamming companion. It would become customary for critics, friends, and even the artist himself to attribute the good humor of the painter and the gaiety of the paintings—apparently two sides of the same coin—to the that “great capacity for happiness” that Redmond developed to compensate for his deafness.

Born Grenville Richard Seymour Redmond (he would later change the spelling of his first name to distinguish himself from his paternal grandfather) in Philadelphia in 1851, the future artist was struck at age two and a half by scarlet fever, an illness that would rob him not only of his hearing, but also of the few words he’d yet learned to pronounce. Redmond never spoke again, and wrote only with somewhat stilted diction for the rest of his life. But what he lacked in loquacity the child made up for in artistic ability. After primary school at the California Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, and the Blind in Berkeley, where he learned to act and took art classes, he was accepted—unusual for deaf students at the time—to the California School of Design. Concluding his undergraduate career with éclat, Redmond hopped a steamer bound for France and enrolled in the Académie Julian.

Although his sojourn in the City of Lights coincided with the artistic efflorescence of the fin de siècle, the young artist struggled mightily. Dependent on financial aid from home, by his account Redmond frequently went about almost in rags and had few friends (he recalled the Norman peasantry as “bêtes” [beasts]). Despite these hardships, it was also a period of technical and academic achievement. Putting aside the figural and historical motifs he’d developed in the States, Redmond turned his attention to the effects of atmosphere. He would write home exultantly of how he’d composed Poesie du Soir (Evening Poetry): “I went out of Paris during night, I looked at the dim moon with a parting of the clouds and I made a crude sketch. Now I have got impression of it. . . . It is uncommon and it is from my own original.” His moody Matin d’Hiver (Winter Morning), depicting a barge shrouded in wintery fog on the banks of the Seine, was accepted to the 1895 Salon.

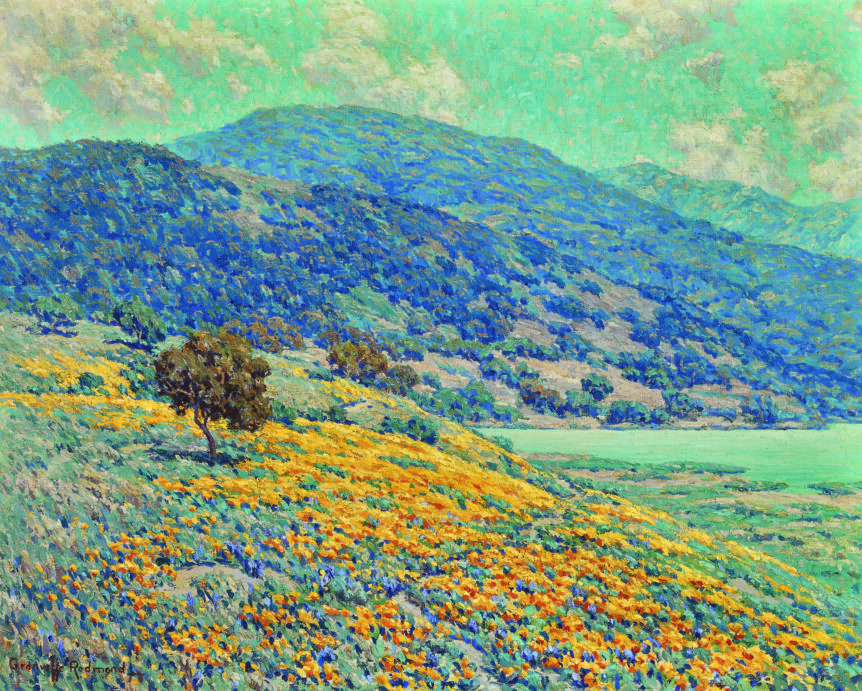

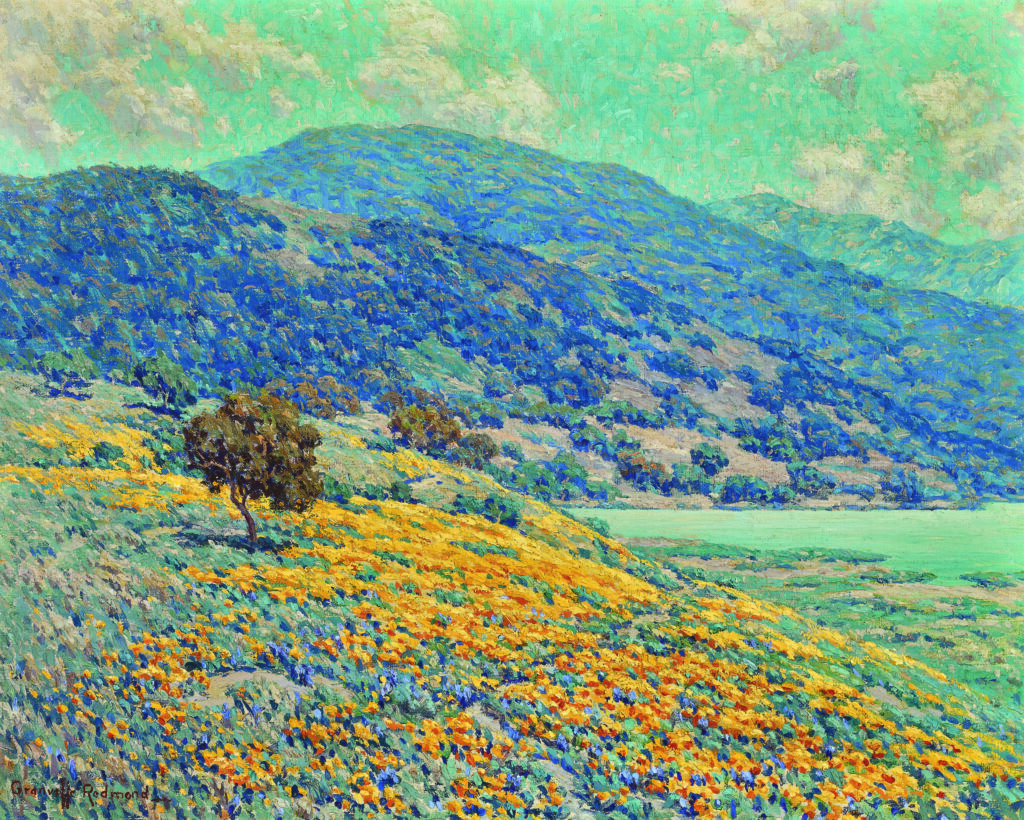

Returning to California, Redmond was delighted with the hues of the ocean, sky, and chaparral, and found himself well-equipped to capture them. Although the saturation of his palette—which is comparable to Signac’s—is the first aspect of Redmond’s work to strike viewers, that burning brightness has become emblematic of California. Paintings like Southern California Hills, Silver and Gold, and the many canvases titled with some variation on “Poppies and Lupine,” remind one of the early photographers of the West, whose salted paper prints show the granite of the Sierra Nevada burning white hot under the heat of the southwestern sun. Over the next three decades Redmond would roam from San Gabriel Valley and Laguna Beach in the south to Monterey and Marin Counties in the north, during which time—if his prolificacy is any proof—he was apparently incapable of cresting a hill without sitting down to sketch. As with one of his favorite writers, Rudyard Kipling, who in his overflowing exultation was wont to end lines of poetry with exclamation points, so it was with each sunny vista Redmond put before the world’s eyes. The canvases seem to shout: “Look at this!”

Granville Redmond: The Eloquent Palette • Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, California • to May 17 • crockerart.org