One of the leading artists of his generation, Charles Wilbert White is perhaps best remembered for his meticulously crafted works on paper. His oeuvre, however, has a significance that resonates far beyond his virtuosic skills and beautifully finished drawings. Profoundly influenced in his youth and early adulthood by progressive thinkers, political activists, the social realist artists, American regionalist painters, and the Mexican muralists, White leveraged his art to expose and interrogate society’s ills—above all, the nefarious legacies born of enslaving Black people in America.

White endowed the people he depicted—nearly all of whom were African American—with a solidity and a solemnity that transcended their two-dimensional forms and invoked the superlatives of human existence. “My whole purpose in art is to make a positive statement about mankind, all mankind, an affirmation of humanity,” White said in 1964. “This doesn’t mean that I am a man without anger—I’ve had my work in museums where I wasn’t allowed to see it—but what I pour into my work is the challenge of how beautiful life can be.”

White was born in Chicago. His mother, Ethelene Gary, had come north in 1914 in the early years of the Great Migration. His father, also named Charles White, was a married man whom the boy would see only on Sundays and who died while Charles Jr. was still quite young. Gary fostered her son’s creativity from the start—first with violin lessons (she herself had musical aspirations), and later with the painting and drawing he embraced with immediate passion. To feed his appetite for artmaking, White scoured the local branch of the Chicago Public Library; roamed the galleries at the Art Institute of Chicago (where he eventually took weekend classes); and sought out and learned from artists in the community. By age nineteen, White was winning awards—two of which were rescinded when prizegivers learned the color of his skin—and the most important of which was a scholarship that allowed him to study at the school of the Art Institute of Chicago full time.

A year later, in 1938, White was chosen to take part in a WPA arts project, working in the unit that painted murals for public spaces. In that program, White completed two powerful works, including 1939–1940’s Progress of the American Negro: Five Great American Negroes for Howard University School of Law, in Washington, DC, where it still hangs today (Fig. 3). Active on the artists’ scene in Chicago, White met artist Elizabeth Catlett, in town on a study visit in the summer of 1941. The two began a whirlwind courtship and wed at the end of the year. They made their first home in New Orleans, where Catlett was chair of the Dillard University art department. The next year, after White won a fellowship from the Julius Rosenwald Foundation, they moved to New York City, where Charles conducted research in the Schomburg Center and studied at the Art Students League. That fall, White and Catlett toured the Deep South for several months, absorbing Black culture and history. In the spring of 1943, White used the last of his fellowship fund to spend several months in Virginia painting a mural for Hampton Institute (now University).

The year 1944 saw a pivotal event in White’s life. He had been drafted into the US Army, and, after basic training, was sent to an all-Black regiment in Missouri, where he was assigned to the camouflage corps. When the Army was called in to help after a flooding emergency on the Mississippi River, White was sent to build sandbag walls against the rising water. Standing in river water for hour upon hour, White contracted pleurisy and tuberculosis. The diseases would plague him all his life, and change the way he made his art.

After White’s recuperation, thanks to a Rosenwald Foundation fellowship won by Catlett, the two fulfilled a longtime dream by traveling at length in Mexico. In the months that followed, White spent time with heroes such as David Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and other greats among the Mexican muralists, in addition to meeting other artists in Mexico City, where he mastered a range of printmaking techniques. Catlett meantime worked on what would become her well-known series of cut-linoleum prints, The Negro Woman. Though the couple’s art-making may have flourished in Mexico, by the end of their time there the fractures in the marriage had become irreparable. They divorced in 1947.

Soon afterwards, White found himself facing another protracted health crisis. He endured several medical interventions for his tuberculosis, which were followed by a period of in-patient convalescence in a Queens, New York, hospital that lasted nearly a year and a half. When he emerged from the ordeal, he discovered a stability in his personal life that helped him achieve his peak as an artist.

White remarried in 1950, as love blossomed with longtime acquaintance Frances Barrett. Couples like them—Barrett was white—were quite rare at the time. The two suffered difficulties and indignities large and small, yet they persevered and thrived together. In the mid-1950s, another series of health mishaps convinced White to follow the advice of his doctors and move from New York to a place with a more salubrious climate. In 1956, the couple moved to Southern California and settled in suburban Los Angeles.

Through all his troubles, White continued to draw, often on a monumental scale. Greater recognition began to come. In 1947, White enjoyed his first solo show, at the prestigious American Contemporary Art Gallery in New York; by the early 1950s, his work was being included in group exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum. Throughout that decade and the next, White’s star continued to rise in response to his powerful artworks, which could evince both trenchant socio-political commentary as well as a profoundly sensitive understanding of the warp and weft of the human condition. In 1967, Los Angeles’s Heritage Gallery published his monograph, Images of Dignity: The Drawings of Charles White. Nine years later, in 1976, White’s successes crested with the September inauguration of The Work of Charles White: An American Experience, his first traveling solo exhibition, which premiered at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art.

White had little time to savor his hard-won laurels. Tuberculosis exacted its final toll in the fall of 1979, when he passed away at the age of sixty-one. “What a beautiful artist Charles White was,” the New York Times art critic Holland Cotter would write on the occasion of a White retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018. “Hand of an angel; eye of a sage.”

The following works of art from the exhibition Charles White: A Little Higher chart the course of White’s career, the development of his artistry, and the evolution and refinement of his sensibilities as an artist.

Awaiting His Return, 1946

Marked by strongly faceted, blocky forms, this work reflects White’s early interest in cubism. Its clarity and directness also remind us of the young artist’s admiration for the Mexican muralists, whom he met in 1946 (the year he created this work) when he and his first wife, the artist Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012), spent several months in Mexico thanks to a renewed Rosenwald Fellowship she had won.

White’s protagonist—a lone, seated woman—is constructed from sharp angles and geometric curves. Her large eyes stare anxiously into an unseen middle distance; the set of the woman’s jaw also telegraphs worried unhappiness, an unease emphasized by the balled fingers of her hand. The cause of her concern is revealed by the Blue Star service banner hanging on the rear wall, for this is the unofficial flag of families whose loved ones are on active military duty.

Created in the same year that the artist’s marriage to Catlett began to fray (they divorced in 1947), this powerful lithograph perhaps reflects White’s own dark mood at the time.

Freeport Columbia, 1946

A visceral commentary on the treatment of Black military veterans by white America, Freeport Columbia melds two harrowing events. On February 5, 1946, serviceman Charles Ferguson and his brothers, Alfonso, Joseph, and Richard, approached the Freeport, New York, bus terminal after an evening out to celebrate Charles’s reenlistment in the US Army. They were stopped by Joseph Romeika, a provisional officer with the local police, on grounds of disorderly conduct. Matters escalated and Romeika shot and killed the uniformed Charles as well as Alfonso, and injured Joseph. The policeman was found guilty of no crimes despite eyewitness accounts reporting that Romeika’s shots were unprovoked and the fact that the Fergusons, who were Black, were later confirmed as having all been unarmed.

At the close of that same month in 1946, a race riot broke out in Columbia, Tennessee. Precipitated by the incarceration of James Stephenson (who was also Black and a veteran of the US Navy) and his mother, Gladys, following a brief altercation with William Fleming (a white store clerk), the Columbia Race Riot culminated with law enforcement officials carrying out warrantless raids and weapons seizures in the town’s predominantly African American business district. One hundred Black men were arrested, twenty-five of them on charges of attempted murder.

White’s forceful image speaks to these horrific abuses of power and race-based violence, leaving no doubt about the predations visited upon people of color in the United States.

Micah, 1964

White here depicts the Old Testament prophet Micah. Monumental in format, this linocut is equally powerful in its visual articulation. The eighth-century BCE biblical figure is turned at a forty-five-degree angle from the picture plane, his gaze firmly locked on a scene not visible to us. White has endowed Micah with a colossal, Moses-like presence. His full-length robes swirl around him, conveying an energy that parallels the prophet’s heightened sense of purposeful, yet agitated emotion. Micah’s prophecies foretold the downfall of ancient kingdoms in the face of humanity’s sinful, impious behavior. His message warns against the dangers of dishonest rulers, false idols, corruption, and greed. Thus, Micah extols us to live a life of rectitude in fellowship with others in our quest for salvation, a message civil rights leaders such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. explicitly incorporated into their own writings, sermons, and speeches.

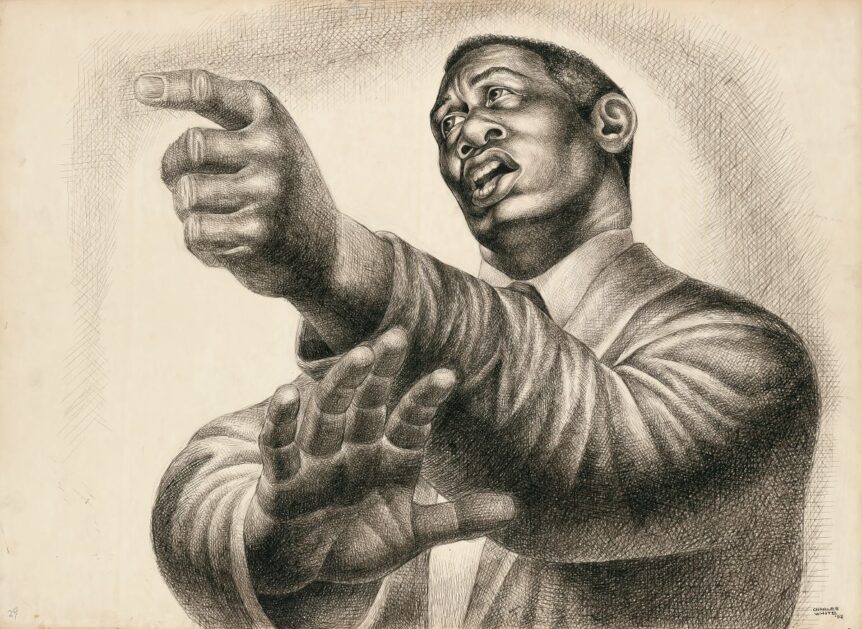

J’Accuse #2, 1965

In 1898, the French writer Émile Zola (1840–1902) published an open letter to Félix Faure, president of France’s Third Republic, on the front page of the newspaper L’Aurore. The headline read, simply: “J’Accuse” (“I accuse”). In his impassioned polemic, Zola defended Alfred Dreyfus, a French artillery officer who, in 1894, had been sentenced to a lifetime of solitary confinement in the Devil’s Island penal colony in French Guiana. Zola accused France’s government and military of complicity, duplicity, fraud, and corruption. He also drew attention to the fact that Dreyfus was Jewish, and lobbed allegations of institutionalized anti-Semitism in France.

White was clearly making reference to Zola and his well-known open letter in this artwork, one of a dozen images bearing the title J’Accuse (followed by a sequential number) that White executed in charcoal in 1965. The grouping was not envisioned as a seamless whole from the start. Rather, the artist made a spontaneous decision to change the works’ titles and unite them under a shared nomenclature shortly before they were shown in his solo exhibition at the Heritage Gallery in Los Angeles that year.

Of White’s J’Accuse works, Ilene Susan Fort has observed that they are “transitional” in terms of the artist’s “fluid yet representational technique that became a signature style.” She further notes that the works evidence the artist’s commitment to shining a spotlight on socioeconomic and social injustices—such as poverty, housing insecurity, and the demands of physical labor—while also delivering messages of hope and dignity.

Wanted Poster #5, 1969

Between 1969 and 1972, White created twenty-one thematically and aesthetically linked works whose powerful imagery was directly inspired by pre–Civil War “fugitive slave” posters and broadsheets advertising auctions of enslaved people. Wanted Poster #5, part of this series, features the beautifully rendered heads of three women of African American ancestry: “Ida,” “Clotel,” and “Edmonia.” Ida likely refers to renowned journalist, abolitionist, and anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells (1862–1931). Above her, White has stenciled “1619,” the year that Angolans were first brought to Jamestown, Virginia, by Portuguese enslavers.

Anchoring the center of White’s composition is Clotel, who looks out at us with defiant strength. Like the protagonist in Black playwright William Wells Brown’s Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter: A Narrative of Slave Life in the United States, White’s figure is held captive by the political power and systemic racism of colonial America, to which the stars that encircle her make reference. This imagery also echoes Brown’s preface to his 1853 publication, in which he wrote, “On every foot of soil, over which Stars and Stripes wave, the negro is considered common property, on which any white man may lay his hand with perfect impunity. The entire white population of the United States, North and South, are bound by their oath to the Constitution, and their adhesion to the Fugitive Slave Law, to hunt down the runaway.”

Completing the trio is “Edmonia,” who is shown in true profile and may pay homage to Edmonia Lewis, the gifted sculptor of African American and Native American descent. Stenciled above her is “19??,” a pointed critique of the unequal treatment of Black individuals, which rhetorically asks when the injustices will end.

Cat’s Cradle, 1972

Five years before his death, White executed this work in the studio of his friend and Otis Art Institute colleague, printmaker Joseph Mugnaini (1912–1992). According to curator Mark Pascale, “[t]radition—artistic and otherwise—was important to White throughout his life. Not unexpectedly, he made his last prints in etching, a printmaking medium with a history dating back to the fifteenth century.”

White created multiple images of children—at rest, at play, or in the arms of their loving mothers—in a variety of mediums over the course of his career. While these works reflect the artist’s persistent belief in the innocence of youth as well as his hope for a better tomorrow, they are no less sophisticated or challenging than the other images in his complex oeuvre. Here, a young Black boy invites us into his world with a direct gaze and unflinching expression. We have interrupted his game of cat’s cradle, making complex patterns in string by progressively shifting designs between fingers.

This image is no simple paean to the uncomplicated pleasures of youth. Rather, it is a deeply complex visual allegory. Consider how the protagonist’s feet are ensnared by two ropes that rise behind him and cross over his head, transforming the boy into a marionette whose agency—and by extension, his destiny—is controlled by an invisible puppeteer. Despite that dark edge, White gives us cause for optimism. Just as he is controlled, so too does the boy exert his own will with the string he manipulates with his hands. The net effect is one of concentrated calm and control.

Money, Merchants and Markets, 1974

This oil and collage was created by White under commission from the Johnson Publishing Company as the opener-image for the tenth and final chapter of Lerone Bennett Jr.’s 1975 book The Shaping of Black America. Like the text it was designed to complement, this image celebrates African Americans’ business acumen, industry, and entrepreneurial spirit.

Anchoring the pictorial field, a man, seated on a chair, studies an oversized sheet of paper lifted from the floor that is reminiscent of architectural blueprints or construction documents. Three schematic diagrams pinned to the wall behind him simultaneously suggest aerial maps, redistricting plans, military operational charts, and Industrial Age machinery. The cryptic words and markings on them, along with the five-dollar bill, might refer to the Civil War period and its legacy in later decades.

The sheets that lie before this man, however, are blank, perhaps suggesting that he has stepped up and out of these nefarious notices from a bygone era to become the master of his own destiny.

Love Letter III, 1977

“For Charlie, the shell became a symbol. In one of his last color lithographs there was astrong, radiant head thrust upward—the head of a woman with a conch shell floating beneath [sic] her. I asked Charlie, ‘Why a shell?’ He answered me, ‘It was one of man’s earliest religious symbols. It represents woman.’ Hugging me, he told me, ‘This is my tribute to the wonderful woman in my life. ’”—Frances Barrett White

The work described above by White’s second wife, Frances Barrett White [1926–2000], in her memoir Reaches of the Heart, is Love Letter III. This color lithograph was the third and final work in a limited series bearing the same name, executed just two years before the artist’s death.

While Letters I and II are associated specifically with civil rights leaders and activists Angela Davis (b. 1944) and Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977), respectively, Love Letter III is a paean to women in general and to White’s beloved wife in particular. They all share the same sensibility—one of feminine devotion to a higher cause.

This article is excerpted and adapted from Charles White: A Little Higher, edited by Jill Deupi and published by the Lowe Art Museum in association with Tra Publishing (2023). All sources for quotations here are cited in the book.

The exhibition of the same name was organized and first presented by the Lowe Art Museum at the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida, from November 10, 2022, to February 26, 2023. It will be on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum in Ohio from November 10 to February 25, 2024.

JILL DEUPI is the Beaux Arts Director and chief curator of the Lowe Art Museum at the University of Miami in Florida.