A world of couture comes alive in the collection of editor Hamish Bowles.

I first met Hamish Bowles, Global Editor at Large for Vogue and Creative Director at Large of The World of Interiors, at a birthday dinner for Peter Dunham, whose book is reviewed in this issue. Since then, he has often referred to his extensive collection of couture, telling me once I approached him about doing this article, that the collection was divided between two locations: London and New Jersey(!) But I was unprepared for what presented itself as I entered Ali Baba’s cave recently with Sarah-Jayne Klucken, who was in situ to help me prepare certain pieces of clothing to be photographed. As she opened the doors to the meticulously organized, climate-controlled storage rooms, I was taken aback by row after row of treasures. When I enquired about photographing a piece by Mariano Fortuny, as the theme of this issue was already moving towards classicism, he informed me that he didn’t have any there. Madame Grès, I then asked about, or Mary McFadden perhaps? “Yes,” was his response to these.

I later surmised that Fortuny, sewn completely without infrastructure, was of less interest to him while I was marveling at the intricate couture machinations going on inside the garments that he had selected for us to shoot. An observer cannot imagine how complex the interior of the simplest Madame Grès dress is until the woman wearing one gets undressed, or you get to be in the presence of these magnificent compositions, but that will be for another article. For the moment, revel in the conversation between two of the most eminent authorities in the field of fashion history: Hamish and his dear friend, running buddy, and editor at large at Air Mail magazine, Amy Fine Collins.

— Pieter Estersohn

Amy Fine Collins: The exhibition of your YSL pieces at the YSL Museum in Marrakech is sublime. It is still ongoing right?

Hamish Bowles: It is ongoing.

AFC: And it is breaking records?

HB: Yes. They haven’t given me figures yet, but I know it’s kind of gone berserk.

AFC: Your vast storage facility is in New Jersey. It must be hard to be so far away from your collection, now that

you have moved back to England.

HB: It is hard, but I have a collection here as well, in London, of all the things I’ve bought in the past three years. Absolutely marvelous pieces, I must say.

AFC: What’s one example?

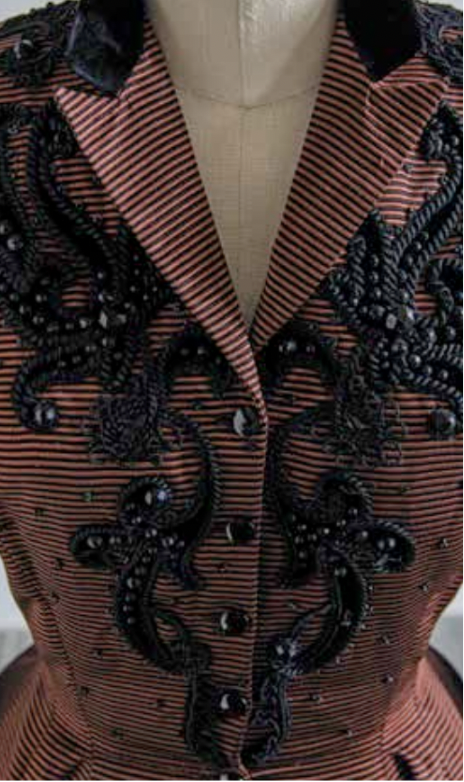

HB: I have a beaded dress from Saint Laurent’s last collection. It was shown as a ballet length, but the woman had it made to the floor. And it’s done with embroidery on tulle, so it’s sort of shimmering ivory on ivory. And also, I have a piece from Christian Dior’s own stint at the house, from 1949. It’s a short evening thing. And it’s made in this fabric which is rather stiff and has a rib in it.

AFC: Is it Ottoman?

HB: Ottoman, that’s right. And it’s scattered with jet beads. The jet beads are few and far between near the hem and at the top of the dress and then they get dense near the waist. And you have a belt that is solid with them. It’s a great dress.

AFC: That sounds very important. Is that from an auction?

HB: It was. It was from an auction in Chicago, and they said that it had belonged to a New York lady. But, it’s very frustrating—they wouldn’t reveal the name.

AFC: Can you picture any particular woman in it?

HB: Someone very, very chic, with a small waist. It would have to be someone who would fit that bill.

AFC: Your storage in England is outside the city?

HB: No, it’s in my apartment.

AFC: Okay. That’s pretty close to you!

HB: She is very close. Gratifyingly.

AFC: Have you set that up yet with the correct climate controls?

HB: No.

AFC: No? So that means that you’re living with your collection the way I am—under the most disastrous circumstances, ones that would strike horror in any curator’s heart. I’m sure you’re planning on rectifying that.

HB: Yes, exactly.

AFC: Whereas I won’t. Because I’m still wearing my things. Last night I was leafing through the Rizzoli Collecting Fashion book and among the photos of the racks in your very packed storage space, one Beene sort of leapt off the page, robin’s egg blue with black polka dots, and gingham. Was that from the Hindman auction that we both participated in, just before the pandemic?

HB: It was. And I got it.

AFC: Yes, you got that. We divided up quite a few things.

HB: Yes.

AFC: A number of the archival Beene pieces from that sale have since resurfaced at multiple locations.

HB: Yes, I’ve noticed that.

AFC: Did you get anything on those occasions?

HB: No, I didn’t

AFC: Okay. Well, next time you see a Beene archival piece for sale, just send a little text to me. It’s easier for me to restrain myself because I’m very single-minded about collecting—I am strictly about Beene—whereas your range goes so much further, wider, and deeper. So if any discipline is exercised on your part, it would have to be by price, quality, and connoisseurship alone, I suppose?

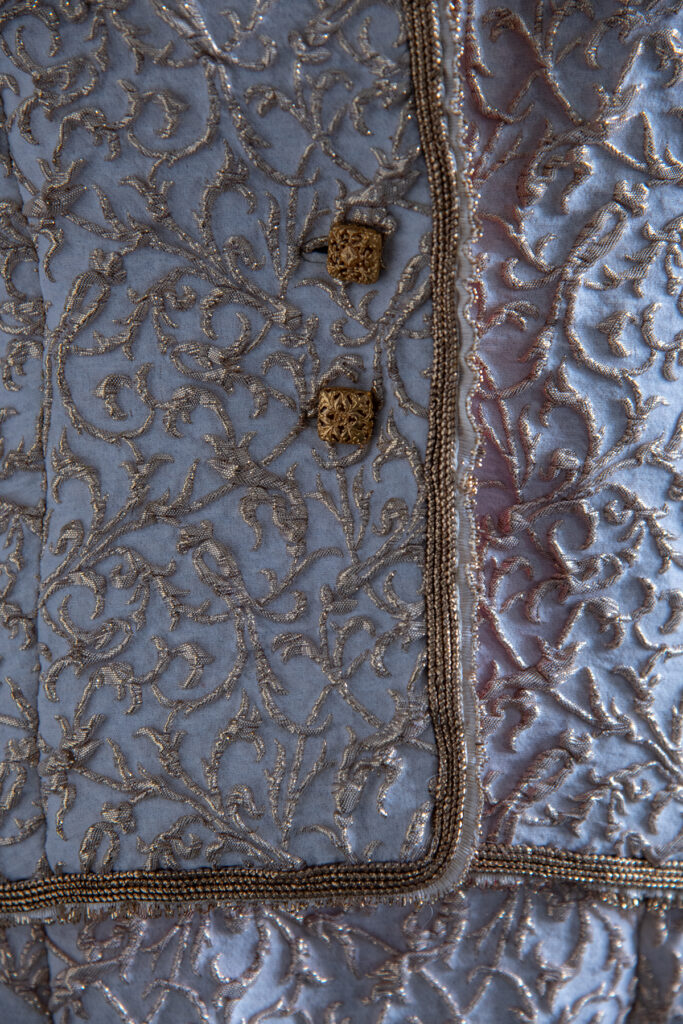

HB:When I first started collecting, I would go to Christie’s South Kensington with my pocket money. I was in my sixth form at school, and would sneak off from my French lessons, careen into the train, and make my way to South Kensington. I got some things including a 1922 Lucille ballgown that’s in silver and gold lamé and is rather becoming. But it was more a learning exercise than about acquiring things. I learned the way each house finishes its dresses—the inside seaming and stitching. They’re rather different from house to house. Dior has one way of finishing a dress and Balmain has another. Schiaparelli is totally different from them, and Chanel is different from Schiaparelli. It’s handy knowledge to have when something comes to you without a label. I’m able to identify something by the way it’s made.

AFC: The way it’s made. It’s like a secret handwriting that only you can read. I do remember seeing your eye catch that sort of detail when we were thrift shopping in New York, back in the nineties, and watching how you immediately homed in on some garment of which only a sliver was showing on a rack. You could always sense exactly what an item was from a distance and with just a tiny detail visible.

HB: Yes, there was a case of that on 25th Street. There was the antique shop on the south side which had all sorts of different vendors. This one vendor rented a tiny booth, and she sort of specialized in estate sales. I was there one day and her store was locked—she’d probably gone out for lunch—and I saw literally a sliver and knew it was Balenciaga. I recognized it to be a black velvet dress of his, to the floor. Around its edge was pearl, gold, and silver embroidery. I saw just the edge. And I waited, waited, waited, and she eventually came back, she pulled it out and it didn’t have a label which was exciting for me because it was absolutely that dress.

AFC: One of our great ladies of the International Best-Dressed Hall of Fame. Tina Chow, another Hall of Famer, had her sale at Christie’s just about the time you moved to New York, right?

HB: I moved in ’92. And her sale was quite soon after that.

AFC: Did you end up with some Fortunys?

HB: No, I didn’t end up getting the Fortunys. Funnily enough, I don’t have any Fortuny in my collection because when I started collecting, I wasn’t very moved by his work. But I think they are sensational when being worn.

AFC: When you got the Gloria Vanderbilt things, were they all Mainbocher?

HB: She was selling anonymously. There was a handsome collection of Mainbocher things I had bought at auction. While researching them, I came across a spread on the best dressed women in Vogue in 1961 or something like that and there was a tiny little picture of Gloria Vanderbilt wearing one of the Mainbocher pieces that I had bought, a gold and crimson brocade sort of theater suit. That is how I identified the anonymous seller. It was a lovely discovery.

AFC: That’s about as exciting as collecting can get.

HB: Moving to New York really opened my eyes to all those incredible style-setting women. As a result, I became interested in lots of different ready-to-wear designers like Norman Norell, Scaasi, Geoffrey Beene.

AFC: And you’ve shifted more into ready-to-wear than before?

HB: I collect important Chloé and early 1970s Sonia Rykiel—that sort of thing. I think anything that holds a mirror up to its time is sort of intriguing.

AFC: I was really happy to see in the Marrakech exhibition one of my favorite pieces—the Saint Laurent patchwork skirt for which you found two examples of the blouse that completed the look.

HB: Christie’s had a vast collection of Saint Laurent pieces belonging to one woman and I had to decide what to go for. Each lot contained about twelve pieces. It was agony because there were good things in all the lots. But anyway, I settled on this one lot. It was intriguing because it included this skirt from 1969, from a patchwork evening grouping that was rather marvelously done. When I researched the skirt at the house of Saint Laurent it was incredible because they had these pages for the staff, and on them were samples of the fabrics listed. There were fabrics from two or three dozen houses and they’d minutely written down the name of each one. Normally a page would have one or two fabric suppliers for each garment and this single garment had fabrics from maybe thirty houses. I was miffed not to have the blouse that went with the patchwork skirt, but time passed, and I got it nonetheless. I was at the Metropolitan, the Manhattan fair where a great many vintage dealers show, and I was getting some quite nice things and suddenly I saw this blouse and I knew that it was the one that went with the skirt. Can you imagine? It was alone in this store—not associated with the skirt. At an entirely different stand, I found the same blouse, only it was a copy done by Orbach’s. They did their copies immaculately well.

AFC: So, it has an Orbach’s label in it?

HB: Yes, it does. But it was just immaculately made, so funnily enough, in my exhibition in Marrakech, I have the patchwork skirt with the Orbach’s blouse because it was fresher than the original blouse.

AFC: It seems like you’re sometimes guided by something beyond yourself —it’s uncanny how these things happen to you recurrently. Yes, these discoveries are a result of extreme knowledge and a lifetime of paying close attention, and an ability to retain all the information that you’ve absorbed visually and otherwise. But also, it just seems like there’s some kind of guiding spirit leading you to these objects.

HB: Yes, exactly. There was this show that lasted three days in Paris. So it was three days’ worth of fashionistas crowding the stands and snapping up whatever they could. And I got in on the afternoon of the third and last day, so I was a bit crestfallen because I thought that everything was probably already gone. But I just wanted to make sure, so I went round it and there was a dress that was used as a backdrop for lots of jewelry—Chanel jewelry—pearls and gardenias and so on, and it had almost obliterated the dress. But it hadn’t quite done that for me because I knew the dress was a sample from Dior in ‘52, I think. It was black velvet, and it was more or less embroidered with black thread. I just started shaking because I couldn’t believe that it was still there. And I said, “How much is the dress underneath all the jewelry?” She was a little alarmed because she knows who I am. And I said, “yes, I’ll take that.” I had my hands clenched on it already, so she gave it to me. I went to the house of Dior the morning after, looking for the sketches from the eveningwear of that season. The sketches were all drawn on Christian Dior-headed paper. When I flipped over a page, there was the dress. It was miraculous. I was very agreeably surprised by that discovery.

AFC: Was it worn in that season’s show, do you know?

HB: Yes, it was.

AFC: Do you know by which model?

HB: No, I don’t. I haven’t seen it photographed in the show, actually. I’m still searching for that.

HB: Ah, that reminds me of another Dior, also unlabeled, that I found at Posh [the erstwhile annual charity sale in Manhattan]. That year I was very much taken with acquiring some of Nan Kempner’s pieces. Her things were in the “boutique” area. There was another huge glass room which had all sorts of clothes. I walked in and the first thing I saw was this 1948 Dior hanging up. I just couldn’t believe it. It had a tiny waist, long sleeves, and a skirt that was pleated to the mid-calf. The pleating was absolutely incredible because each pleat was not really a pleat. It was stitched—they’d inserted a narrow triangular thing, to give it movement. And the “pleats” went all the way around the skirt. It must have taken hours, I mean, hours to make. And it didn’t have a label. And I said, “Ooh, how much is this?” And it was $25. So, I said, “I’ll take it,” and when I was doing my research, I found the woman wearing it on the runway, in the Dior house on Avenue Montaigne. She has on a big straw hat. So things like that are kind of wonderful.

AFC: Well, they do bring up goosebumps. Any idea whose dress it was?

HB: No.

AFC: Who in New York would have been buying that in 1948? Was it a sample or was it something that a New

York woman had ordered?

HB: It could have been either/or. If it was ordered by someone, whoever it was had a minute waist.

AFC: I always liked the idea you had of making a foundation out of your collection. Perhaps it will still happen?

HB: Yes, I think I would like it to sit in a museum or an institution of some kind.

AFC: I could see the whole collection belonging to the V&A eventually, but it’s premature to talk about that because yours is still such an active collection. Maybe there’s a little more competition now in acquiring?

HB: Yes. Though I have the advantage because, when there is no label, I can still tell what something is by

how it’s made and finished.

AFC: Is there something that you’re seeking—a Holy Grail that has not yet landed in the collection?

HB: Well, I think an early Poiret would be nice. Poiret was always, always something that dealers and museums collected even when I started, back when I was sixteen and seventeen. It’s a tricky one.

AFC: I am supposed to inquire about the psychological drive behind your collection—the psychological, emotional, “why?” What would a psychoanalyst’s explanation be?

HB: It’s like having a piece of someone’s life before you, capturing it. And it’s so touching, almost because these

clothes show such power.

AFC: The clothes are synecdoches for the humans who occupied them. And it is very poignant, when we

consider how these things outlive their owners. These fragments of a life have such an afterlife.

HB: Yes.

AFC: And you don’t have to deal with the messiness of actually knowing the person.

HB: [Laughs]

AFC: Do you have anything that belonged to Natalia Paley that you know of ?

HB: I do have some things.

AFC: Oh, you do have some things! From Mainbocher?

HB: Yes, exactly

AFC: Not from Lelong?

HB: No, alas, not.

AFC: The exhibition I told you about at the Hillwood Museum on Natalia Paley just opened. So, let’s make a date to go to DC to see it whenever you are next in the US.

HB: Yes, absolutely! Well, bye-bye.

AFC: Till soon. Yves Saint Laurent: The Hamish Bowles Collection will be on exhibition at the Yves Saint Laurent Museum in Marrakech, Morocco until January 4, 2026.

AMY FINE COLLINS: is a fashion and design journalist, editor at large at Air Mail, contributing editor (New York) at The World of Interiors, and co-owner of the International Best-Dressed List, now in its 85th year.