Arader Galleries reveals the astonishing watercolors of Maria Sibylla Merian, a rare woman naturalist in eighteenth-century Germany.

On a cold winter’s evening, I stepped into one of Manhattan’s most quietly remarkable troves of art and rare books. This discovery of Arader Galleries’ flagship on Madison Avenue became the first of many visits. Housed in a beaux arts-style mansion, each room is its own microclimate of rotating works.In one such room, I encountered the watercolors of Maria Sibylla Merian.

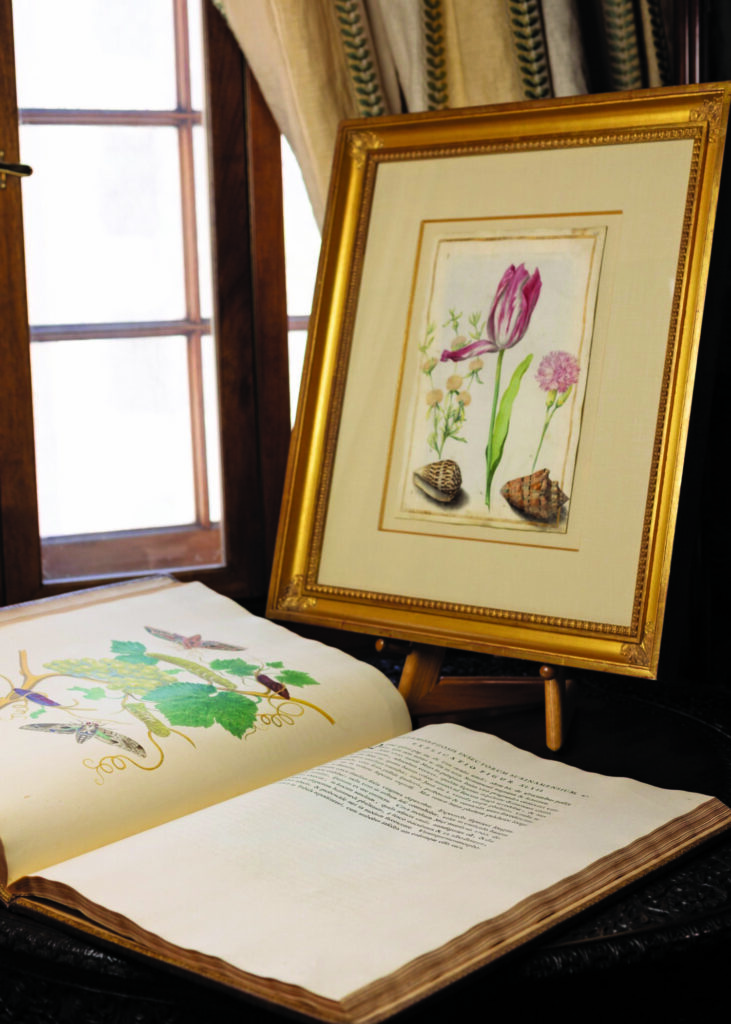

Gallery representative Michael Harper—whose enthusiasm for Merian’s work is infectious—led me to a table by the window where a large folio lay open: Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. Published in Amsterdam in 1705, it is Merian’s meticulous study of the flora and fauna of Suriname, then a Dutch colony. On the open page, a pineapple appeared so ripe that it was fragrant, flanked by green butterflies and roving caterpillars. One can appreciate the novelty of many of the specimens when the book was printed over three centuries ago.

What makes Merian so extraordinary—then and now—is not only her artistry but her independence. At a time when women rarely traveled on their own mission, she set sail with her younger daughter, Dorothea, in 1699 for South America, without official sponsorship. She endured a two-month voyage across precarious and remote waters, and spent two years in Suriname documenting plants, insects, reptiles, and amphibians in their natural habitats. Unlike many naturalists of the age, she rejected the practice of studying pinned, lifeless specimens. Instead, she observed living creatures through their full life cycles, making meticulous notes on their metamorphoses and fragility in their respective ecosystems.

Her Metamorphosis offered European readers their first glimpse of the tropics from the direct observation of a female artist. It was as radical in method as it was in authorship. Harper turned more pages: an arresting depiction of a crocodile wrestling a snake; a hibiscus animated by pollinators; and in the pineapple plate, the delicate notation that its flavor was “like a mixture of grapes, apricots, currants, apples, and pears.” Alongside these Suriname items, Arader holds some of Merian’s European botanical works. They fuse flowers with seashells in a cabinet of curiosities style.

In one watercolor, a feathered pink tulip rises between a carnation and a chamomile sprig and two conch-like shells: a Conus spurius from the West Indies and a Voluta musica from the Caribbean. Such “broken” tulips were among the most prized blooms of the seventeenth century. These images are more than beautiful—they are records of trade, empire, and scientific ambition. The shells arrived in Dutch ports on ships from the East and West Indies, feeding a market so intense that the rarest specimens were as valuable as fine jewelry. To see them paired with flowers in Merian’s hand is to glimpse the era’s obsession with rarity and display.

Harper points out that Merian’s Suriname book, represented here in the 1719 Latin second edition with sumptuous counter-proof plates, was marketed to “all lovers and investigators of nature”—both the art connoisseur and the amateur naturalist. Buyers could choose uncolored or hand-colored sets, the latter finished in her workshop with dazzling precision. Arader’s example, once in the library of Shirburn Castle, is among the finest extant.

That such a body of work was created by a woman—trained in her stepfather’s studio, divorced, self-financed, and undeterred by illness—is reason enough to call it a hidden gem. But in the intimate setting of Arader’s upper rooms, free from the bustle of a museum, these works are revelations. You can stand inches from the vellum, see the fine cracks in the paint where Merian’s hand layered body color over ink, and imagine her, three centuries ago, shaded in a Suriname garden with magnifying glass in hand, watching a moth emerge.

As Harper closes the book, the pineapple disappears from view, but the encounter lingers—a reminder that some of the most radical voyages in art and science began not with official patronage, but with one woman’s resolve to see for herself.