In many ways the challenges of the dramatic new exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum are its subject matter. Beginning with the title, Unnamed Figures: Black Presence and Absence in the Early American North, visitors are on notice that they will be witnesses to an investigation of the unknown and the partly known—not to mention the misunderstood and the misrepresented. To some extent this should make even the most casual museumgoer an active participant in rethinking history and art history, something the curatorial staff clearly intended, and something that should lift the exhibition beyond argument to enlightened exploration.

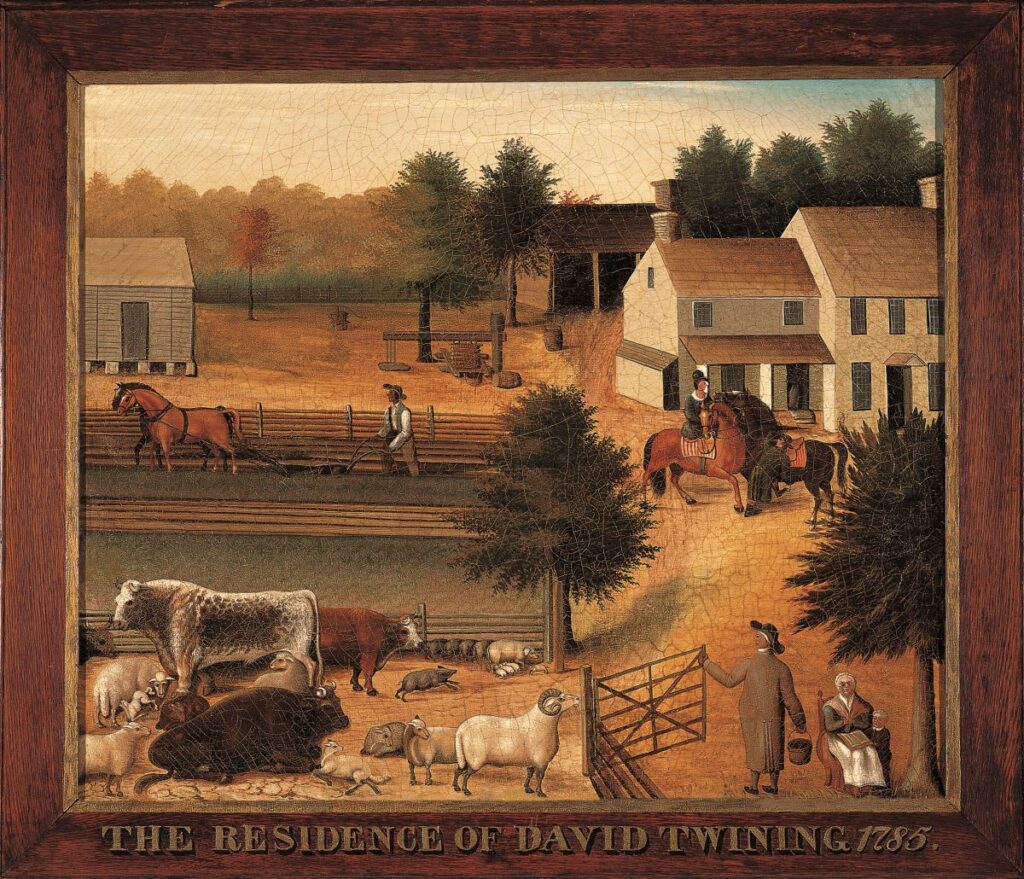

For the folk art follower, Unnamed Figures may also come as something of a shock, or perhaps a shock of recognition. A glance back at the Whitney Museum’s 1980 landmark exhibition, American Folk Painters of Three Centuries, or its opulent book, will remind anyone who saw that celebrated show that out of the 115 images from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries only one showed a Black person—the miniscule figure at the plow in Edward Hicks’s Residence of David Twining 1785 (Fig. 3). In the twentieth-century section there were no Black people except for those in the portion on Horace Pippin. Closer to home and closer to the present, American Anthem: Masterworks from the American Folk Art Museum (2001) included no Black figures (except for enslaved people depicted on a wooden Game of Chance) until, again, the twentieth-century section, which included many fine works by Clementine Hunter, Sister Gertrude Morgan, Ralph Fasanella, and others.

Fig. 2. Perry Hall, Home of Harry Dorsey Gough, Maryland, c. 1795–1798. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 by 53 1/2 inches. Winterthur Museum, Garden, and Library, Delaware, gift of Henry Francis du Pont.

Why the absence? After all, paintings of enslaved figures as well as other early representations of Black people have long been in museums and private collections, and many of these are now on loan to Unnamed Figures, and yet the idea of including such images must have given earlier curators pause. How could they integrate them into an omnibus of celebrated folk art without providing the kinds of scholarship, context, and comment that now inform this pathbreaking exhibition?

It took quite awhile to get to this moment. Historians like Sean M. Kelley have recently corrected the ways in which early histories of New England obscured the unpleasant facts: slave trading before the Revolution was, in fact, the province of New Englanders; numbers of New Englanders owned slaves; and after the Revolution there was a substantial free Black population. The record is established, and it is the mission of this exhibition to acknowledge it, build upon it, and go forward to interpret its visual legacy in New England and other parts of the North.

If there is an emblematic image here, one that informs the trajectory of the exhibition of identities lost and found, it must be the oil painting Perry Hall, Home of Harry Dorsey Gough (Fig. 2). Emelie Gevalt, curatorial chair for collections and curator of folk art at the museum, has done a deep investigation of this large domestic landscape, pointing out that the names of every figure in it are a matter of historical record . . . every figure, that is, except the Black nursemaid. Her research suggests that the girl may be Sib Hall, who was born on the plantation (Fig. 2a). She has gone on to trace Sib Hall’s children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great-grandchildren, providing images of them well into the twentieth century (Fig. 18).

It’s an illustrious history, Gevalt writes in the catalogue, of “Black persistence and achievement.” Whether or not the image in the painting is actually that of Sib Hall or a near contemporary of hers, Gevalt’s research points the way to what follows: “Most early Black representations do not lead to findings of such depth,” she writes, and most figures, but tracing these early histories leads to fruitful questions shifting “our expectations from early American art and its museum spaces.”

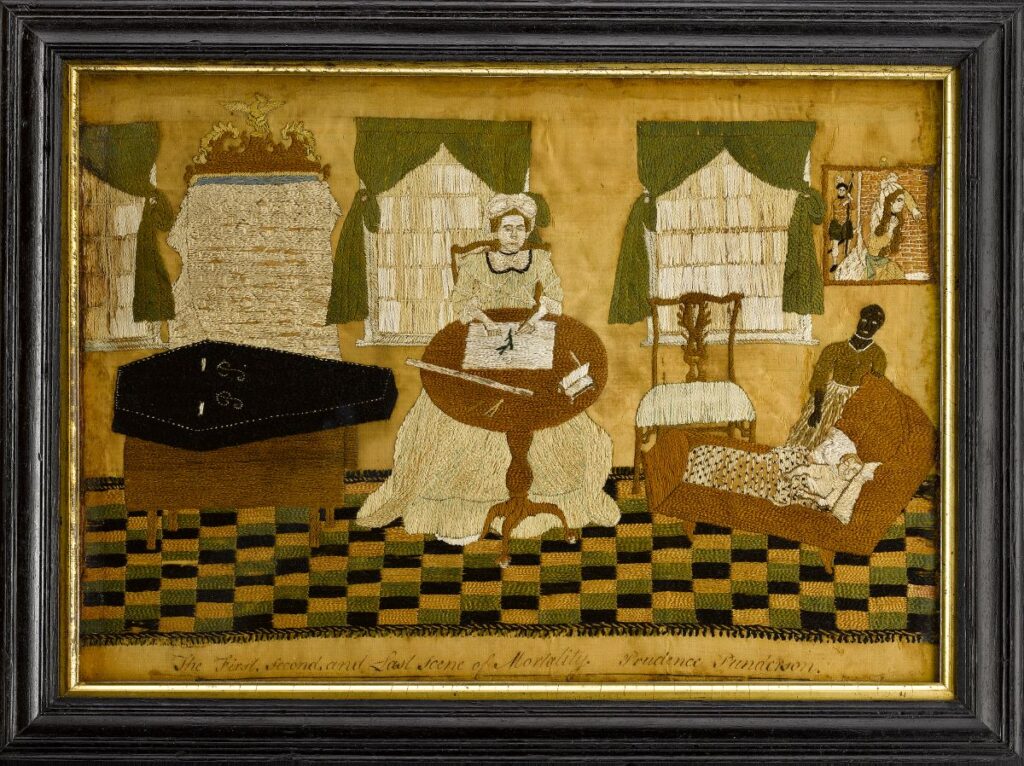

Here is an example: Connecticut artist Prudence Punderson’s famous autobiographical needlework, The First, Second, and Last Scene of Mortality (Fig. 4), with its depiction of baby Prudence’s nurse Jenny Cato at the far right. The wall label informs us that Cato’s life did not end at the margin of the needlework. She went on “to secure her freedom, move to New London, and marry twice. Remarkably, she produced a will which begins with a simple assertion of self: ‘I Jane Cato.’” Providing this kind of information in an exhibition is not a matter of grafting present concerns onto the past. This is the past.

As visitors walk along the galleries, a number of familiar works may look a bit different now. Admirers of Edward Hicks’s aforementioned Residence of David Twining will notice the matter-of-fact way in which the tiny unnamed Black figure at the plow is isolated in the composition. The wall label suggests that his name may have been Caesar, and in an even-handed approach to the work emphasizes Hicks’s Quaker values, leaving both the contradiction and the beauty of the painting intact.

Here as elsewhere the goal is not to have viewers dismiss problematic works, but to make them look again to see what has been overlooked. In the landscape section of the exhibition, the Van Bergen Overmantel (Fig. 5) attributed to John Heaton is good example of a calm, almost routine, scene of farm life where the Van Bergens relax while a number of enslaved and free figures perform the tasks that keep the farm running. This is the Hudson River valley in the eighteenth century, and it’s an eye opener.

There are, of course, many other families depicted in the show, some of them posed much more intimately with enslaved members of the household than the Van Bergens. Of these, John Potter and Family stands out—though it is not alone in its inadvertent depiction of Black dignity amidst a smug, repellent family portrait (Fig. 6). The Potter family of Rhode Island is shown taking tea; they have a young Black servant who is either there to fill out the frame or as an emblem of their status. Whatever the case, he is not taking tea, nor is he named. He simply draws your eye away from the family. We know a lot about John Potter, a notorious enslaver and counterfeiter, but we do not know if he perceived the irony embedded in this portrait—or if the artist did.

The title John Potter and Family has not been adjusted to reflect the presence of everyone depicted, but in other family portraits the unnamed have been belatedly acknowledged. Charles Calvert and Once-Known Enslaved Attendant was formerly known as Charles Calvert and his Slave (Fig. 1). Several works in the exhibition have been similarly retitled in recent years, and the catalogue has a sparkling article by Jennifer Van Horn and Virginia Anderson of the Baltimore Museum of Art illuminating the reasons for doing so. It’s no small matter, and, as they note, in many cases titles both past and present are provided as a “reflection of the objects’ multilayered histories within multiple collections.” For this and many other reasons, the catalogue is a fine and perhaps essential companion to the viewing experience.

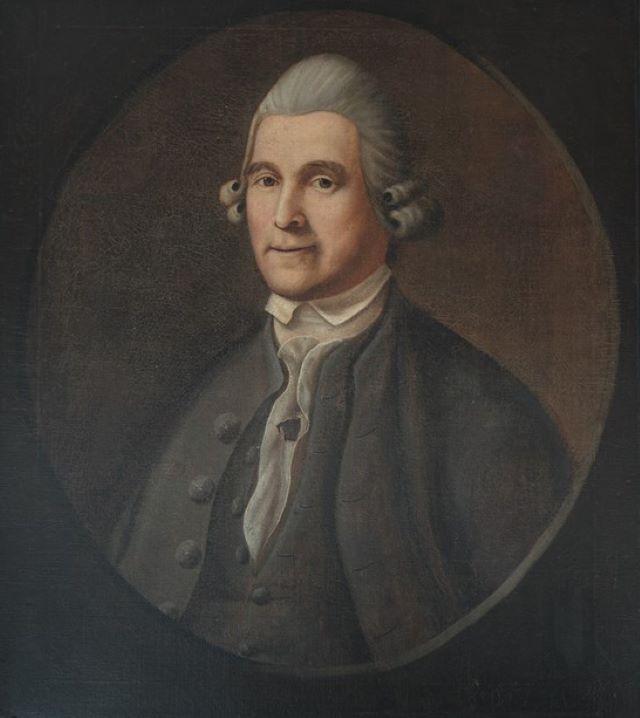

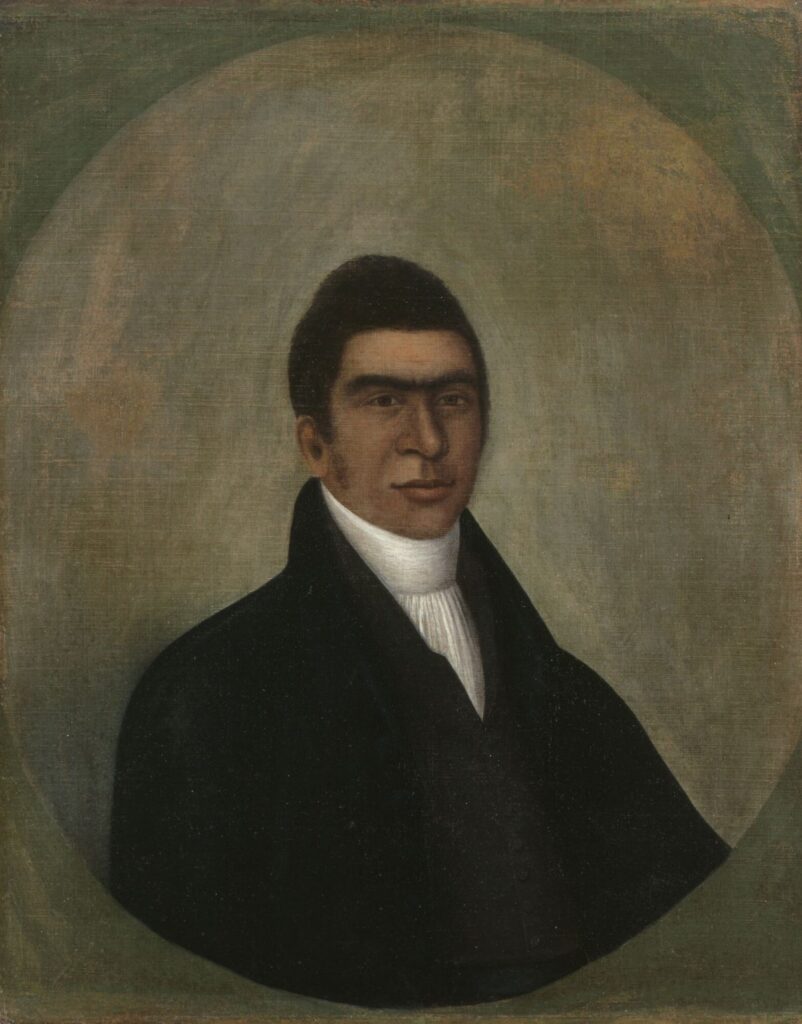

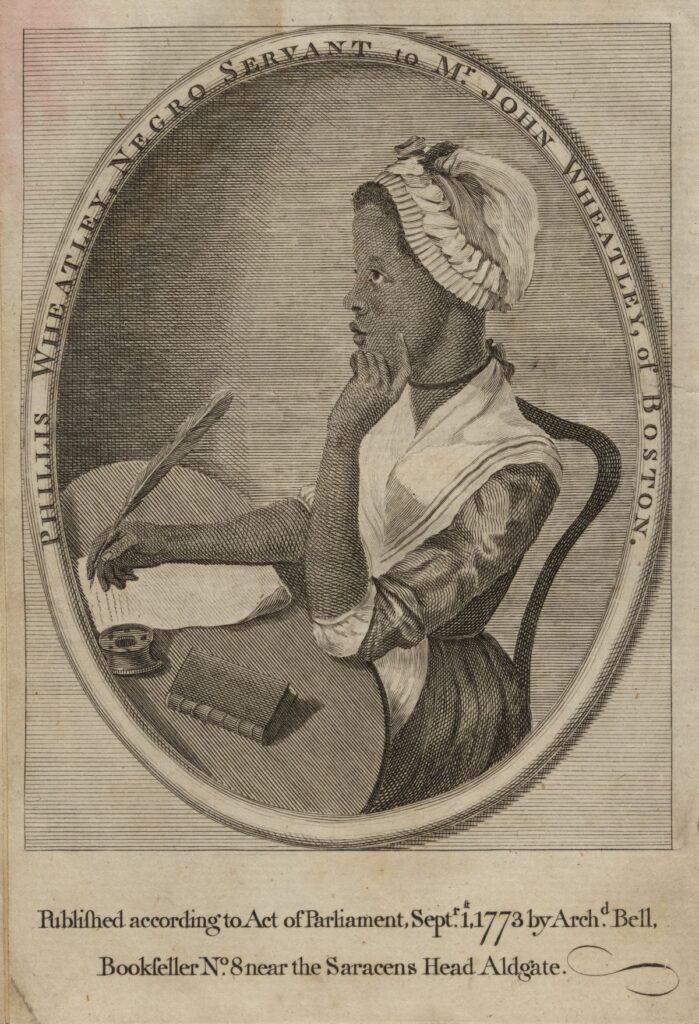

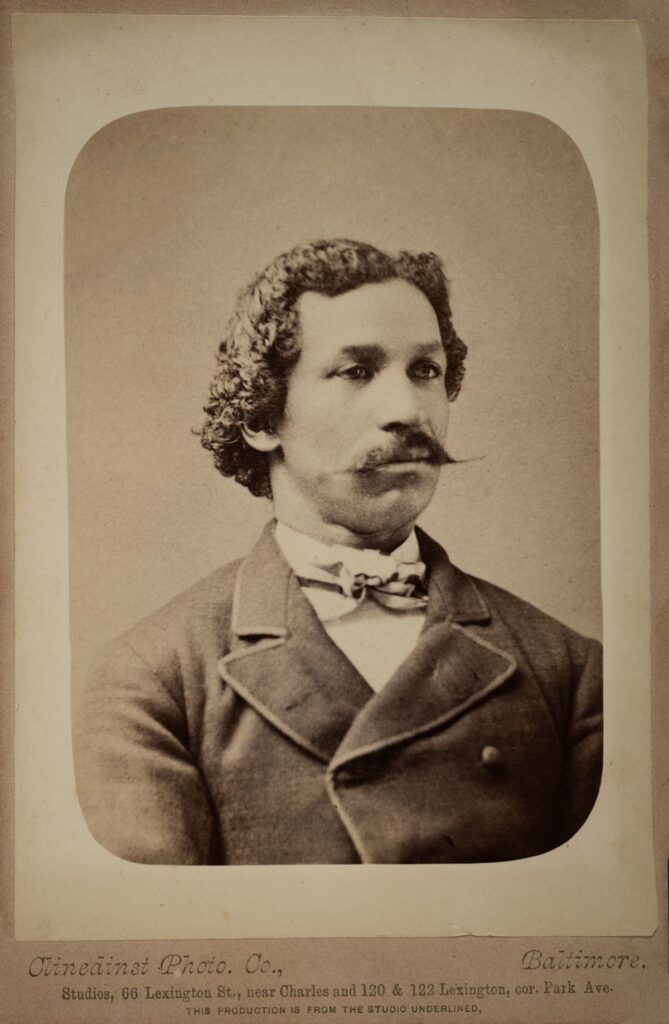

When the exhibition shifts its attention to a section on Black artists and artisans, viewers will be pleased to see two portraits by Prince Demah, the enslaved painter whose Portrait of William Duguid (1773) in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Interwoven Globe exhibition of 2013–2014 all but stole the show. Enslaved by Loyalists, he gained his freedom, joined the Patriot cause, and died during the war. Only three known works by Prince Demah survive and two of them are here (Figs. 8, 9). He is joined in this section by well-known figures like poet Phillis Wheatley (Fig. 12) and artist Joshua Johnson (Fig. 10) as well as by lesser-known but no-less-intriguing figures such as the carver John Bush, illustrator Peter Fleet, polymath Benjamin Banneker, and others. Taken together, these named figures are a welcome counterpoint to all that has vanished—including images of several of them.

After emancipation, Black northerners began to play a more prominent role in our visual history. Not surprisingly some of that history is overtly racist, as in notorious works like Town Scene (formerly known as “Darkytown”) (Fig. 11), later satirized so effectively by Kara Walker. Some of those racist works are shown, as they should be, but so are the two excellent portraits by William Matthew Prior commissioned by Nancy and William Lawson (Figs. 13, 14) as well as other dignified images of named figures. That Prior’s similarly situated contemporary Ammi Phillips (1788–1865) did not paint any Black people does not pass without notice; two of his portraits are here, their white sitters named. Point made.

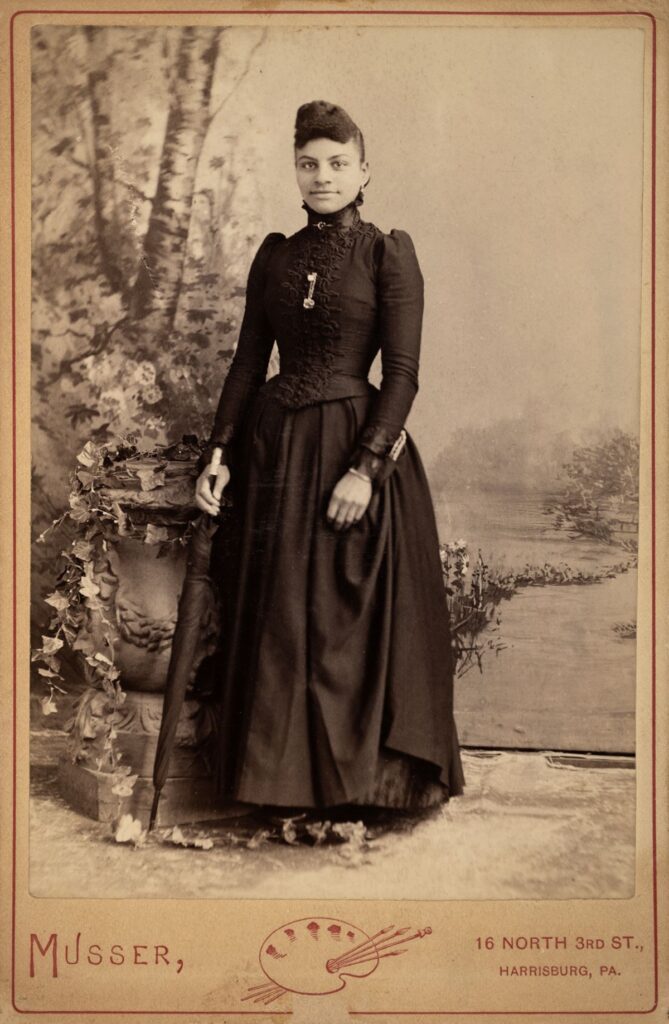

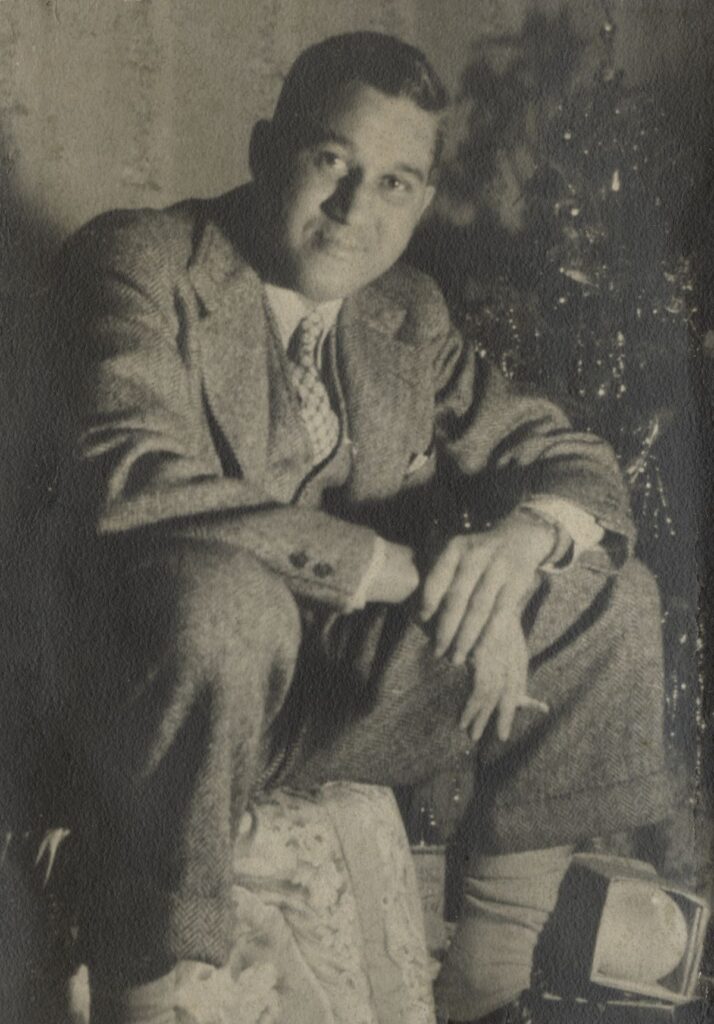

The exhibition ends with fifty-six images from the Burns Collection and Archive of early photographs: cabinet cards, tintypes, daguerreotypes, and so forth, a varied trove of Black people of many ages in all manner of dress and postures from the second half of the nineteenth century and first quarter of the twentieth. This, at last, is the rich visual record of Black lives we have been missing. They are here. Few of them are named.

Unnamed Figures: Black Presence and Absence in the Early American North is on view at the American Folk Art Museum from November 15 to March 24, 2024. It will later travel to Historic Deerfield in Massachusetts.