The genesis of most private museums, especially those that proudly bear their founder’s name, goes something like this: a plutocrat, usually a man, is initiated into the rarefied sport of collecting; then, at some point past the age of fifty, as immortal longings kick in, he decides to eternalize his treasures by constructing an impressive building to contain them. Such was largely the case with the Morgan Library, the Frick Collection and, more recently, the Broad museum in downtown Los Angeles.

Very different, however, were the origins of the Hispanic Society, which proudly occupies its portion of Audubon Terrace, a complex of cultural institutions on Broadway and 155th Street in northern Manhattan. Recently rebranded as the Hispanic Society Museum and Library, it was founded in 1904 by Archer Milton Huntington (1870–1955), heir to one of America’s greatest fortunes, that of Archer’s stepfather, Collis Potter Huntington, who co-founded the Southern Pacific Railroad. He was still in his early teens when he started to dream of a great institution that would one day house the art and books that he had scarcely begun to acquire. One of the greatest collectors in an age that included Henry Clay Frick, Isabella Stewart Gardner, and the Havemeyers, Huntington, in an autobiographical work written at the age of fifty, described his first trip to Mexico, at eighteen, as “a sort of strange awakening. . . . From now on the road was clear . . . my museum dreaming became clear and took on new forms.”

Today the museum and the magnificent library that resulted (nearly twenty years later) from that trip to Mexico are closed for much-needed renovations under the guidance of the society’s director, Mitchell A. Codding, and chairman of the board, Philippe de Montebello, formerly director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The most notable part of its redesign—entrusted to the architectural firms of Annabelle Seldorf and Beyer Blinder Belle—consists of integrating the building to its east that once housed the Museum of the American Indian and that will now display the society’s temporary exhibitions.

But the first objective of the society is to increase the public’s awareness of the fact that it even exists. Though Washington Heights—the neighborhood where the museum is located—becomes more gentrified by the day, the society is still largely unknown to most Manhattanites and even more so to tourists. Indeed, it is apt to seem almost incongruous that, in one of the city’s most resolutely working-class neighborhoods, a complex of gleaming marble palaces, among the most splendid of the Belle Époque, should rise up in gated isolation to house one of the noblest collections of Spanish art and culture ever assembled. In addition to the museum’s more than twenty thousand works of art, the library contains 250,000 manuscripts, thirty-five thousand rare books, and over two hundred thousand titles of more recent vintage.

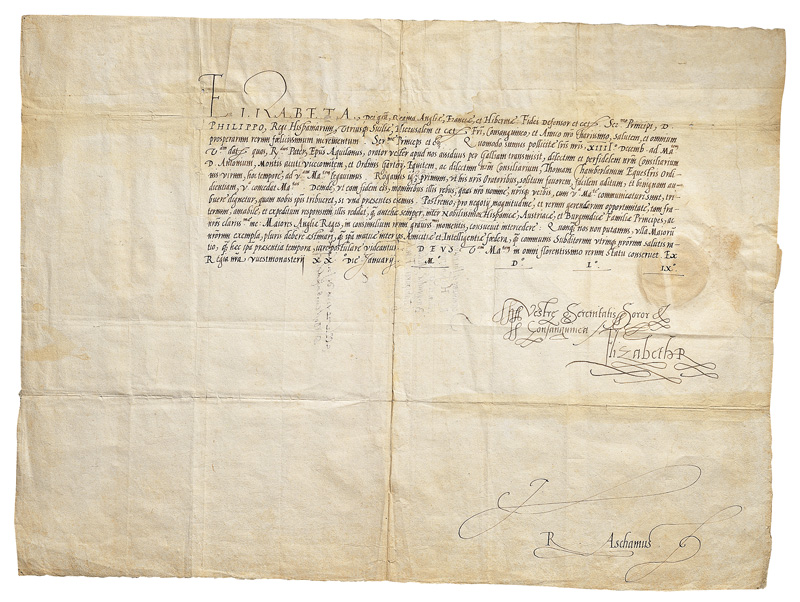

To promote the institution while the work proceeds, a traveling exhibition, Visions of the Hispanic World: Treasures from the Hispanic Society Museum and Library, opened last fall at the Cincinnati Art Museum under the name Treasures of the Spanish World (after stints at the Albuquerque Museum in New Mexico and the Prado in Madrid). From there it will move to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. (A sampling of the society’s rich holdings will also be on view as the loan exhibition at the Winter Show, the noted art and antiques fair that opens at New York’s Park Avenue Armory on January 24.) Even in this drastically abridged form, the collection’s spectacular breadth and excellence is attested to by the more than two hundred objects in the show. No aspect of the material and visual culture of Spain and its colonies (as well as Portugal and its colonies) escaped the acquisitive impulses of Archer Milton Huntington. The objects on view range from prehistoric pottery and a Roman mosaic to medieval Moorish ivories and a letter from Elizabeth I of England to Phillip II of Spain (Fig. 9).

But the main draw of the show, surely, will be one of the finest collections of Spanish paintings outside of the Iberian Peninsula. It includes such masterpieces as El Greco’s Saint Jerome (Fig. 4), Murillo’s Prodigal Son Among the Swine (Fig. 8), and Zurbarán’s Saint Emerentiana (Fig. 6). Few of the Prado’s works by Velázquez can surpass the Hispanic Society’s majestic full-length portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares or the charming Portrait of a Little Girl (Fig. 5). The society’s holdings of Goya are even more extensive, including his great full-length portraits of the Duchess of Alba (Fig. 7) and Manuel Lapeña, as well as numerous satirical works on paper. The exhibition also displays some of the earliest and finest photographs of the Alhambra in Granada and paintings by such turn-of-the-century masters as Joaquín Sorolla, represented by a fine portrait of Louis Comfort Tiffany (Fig. 2), and the Basque Ignacio Zuloaga, with his moving Family of the Gypsy Bullfighter (Fig. 11).

As these treasures attest, the Hispanic world, in all its breadth and diversity, from ancient times to his own day, engaged Huntington’s all-conquering acquisitiveness. But that world meant something different in 1900 from what it means today. Although the United States’ influence now extends to every corner of the earth, this prodigious hegemony has caused the nation, paradoxically, to turn its back on its own hemisphere. Before the First World War, however, when Huntington was establishing his museum, our involvement with the rest of “the Americas” was far more energetic. England, France, and Germany might be our spiritual ancestors, but Spain’s former colonies were our next-door neighbors, indeed—after the Spanish-American War of 1898—some were our new possessions. Thus the deeds of Cortez and Ponce de Leon, as documented in the archives of Seville, engaged with our national history in a way in which the Wars of the Roses and France’s Wars of Religion, for all their color and pageantry, did not.

At the same time, Huntington’s embrace of the Hispanic world—although a somewhat exotic taste at the time—was entirely of its age. His conception of Spain was colored by romanticism and especially by the lingering enchantments of Washington Irving’s Tales of the Alhambra. And yet, Spain and its colonies still represented a largely undiscovered civilization that stood in stark contrast to the primly Protestant, Anglo-Saxon culture of the United States and to the Francophile longings that dominated so much of the nation’s official taste. If Huntington had chosen to collect Italian and French art or early editions of Shakespeare and Milton, no one would have found that choice to be remarkable in the least. But to consecrate so much wealth and energy to the Iberian Peninsula and its New World possessions was as inspired as it was unforeseen. It also seemed fundamentally “American,” in the broadest hemispheric sense of the term, and thus somehow patriotic. This was, after all, the age when the cult of Christopher Columbus—who has fallen on such hard times in recent years—reached its storied summit in Chicago’s great Columbian Exposition of 1893.

At the Hispanic Society, the architectural expression of this love of Spanish culture is the great two-story central gallery, the Main Court, where the museum’s finest paintings are displayed against a backdrop of lavish crimson (Fig. 1). It is almost as though this chamber—designed by Charles Pratt Huntington, a cousin of the founder—were an Iberian riposte to Isabella Stewart Gardner’s roughly contemporary Venetian palazzo in Boston’s Fenway. With its elaborate wooden ceiling and busily mannerist arcades at ground level, it takes us back, almost as though it were a stage set, to the Spain of Charles V in the middle of the sixteenth century.

But the rest of the building that houses that gallery, like the seven other structures that occupy Audubon Terrace, was conceived in a far more classical key. The entire complex—except for two buildings used by the American Council of Arts and Letters and the National Institute of Arts and Letters, by McKim, Meade, and White—was originally designed by Charles Pratt Huntington on land that Archer Milton Huntington purchased and donated for this purpose. Separated from Broadway by an ornate gate and resting on an elevated platform, Audubon Terrace represents an eminent example of the so-called City Beautiful movement, which marked the introduction of beaux arts notions of design and urbanism into the cities of the United States. The exterior of the Hispanic Society, with its giant Ionic columns, balustrades, and pedimented entrance, fully embodies the classicizing aspirations of the age. A frieze near the top proclaims the names of Bolivar, Cervantes, Velázquez, and Lope de Vega, among others—dead white males, as so many of our contemporaries are inclined to call them today.

It is easy to make fun of the dominant aesthetic postures of a century past, the very ones enshrined in the architecture of the Hispanic Society Museum and Library, as well as all the other structures that inhabit Audubon Terrace. On reopening in the coming years, the society, like most of the other cultural institutions of our day, will engage more vigorously with contemporary art and engage in far more robust outreach to the local communities. That is necessary for its survival. But it must take care—as its board surely understands—not to yield too much to the passing tide. Even if no better case could be made (as it can be made) for the society than as a relic of a vanished age, nevertheless it so fully exemplifies that age that, by itself, that fact would be reason enough for us to cherish the institution and to fight for its survival. But it is, of course, so much more than that, and as word of its treasures and charms and new enhancements spreads, it will be well positioned to prosper and outlast the fashions of the moment.

Treasures of the Spanish World is on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum to January 19, 2020.