In early 1881 Winslow Homer voyaged to London and took up residence in the English coastal village of Cullercoats through the following year. At first glance, it appears to have been an odd and unexpected move. Homer had not traveled to Europe since going to France in 1867, nor would he again. His relocation, moreover, came at a professional moment that seemed not especially transitional: by the second half of the 1870s he was a fixture on the American art scene, with his depictions of bourgeois leisure and rural simplicity, such as The Dinner Horn (Fig. 3) and Croquet Scene (Fig. 4), featured in gallery and society exhibitions in New York and Boston. Homer’s impetus for traveling to England can only be a matter of conjecture, but two key developments in the 1870s—one in the larger American art world, the other in Homer’s career—may have inspired his journey.

Fig. 1. Hark! The Lark by Winslow Homer (1836–1910), 1882. Signed and dated “WINSLOW HOMER/ 1882” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 36 3/8 by 31 3/8 inches. Milwaukee Art Museum, Layton Art Collection Inc., gift of Frederick Layton; photograph by John R. Glembin.

The first of these was a burgeoning critical interest in and identification with British art in the United States, which reached its height at Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial Exhibition. One critic observed, “almost everywhere the flaming sign of Great Britain meets the eye.”1 Although fewer than 10 percent of the oil paintings at the centennial were by British artists, critics maintained that the selection provided the first comprehensive introduction to British art for many Americans. “There are few disciples of the [British] school, who, in the eyes of the devotees to technique, would be judged skillful manipulators,” the writer for the American Architect and Building News reported. Yet, like the common language and literature that yoked the United States and Britain, the visual art of the two countries shared certain idioms: above all, the British paintings exhibited a forthrightness, “a direct and comprehensive way of telling a story,” that was immediately accessible to American audiences.2

Whether Homer saw the display in Philadelphia is unclear, although seven of his works were included in the American section. He surely would have followed the art criticism and been aware of the fervor for British painting, building as it did on a growing interest begun with American collector John Taylor Johnston’s acquisition of James Mallord William Turner’s celebrated Slave Ship (Fig. 5). Due to the enormously popular writings of the critic John Ruskin—an avid supporter of Turner and his legacy and the original owner of Slave Ship—the artist was viewed, on both sides of the Atlantic, as Britain’s finest painter. Because few of Turner’s paintings were in American collections, familiarity with his work came largely from Ruskin’s frequently reprinted Modern Painters, first published in 1843.

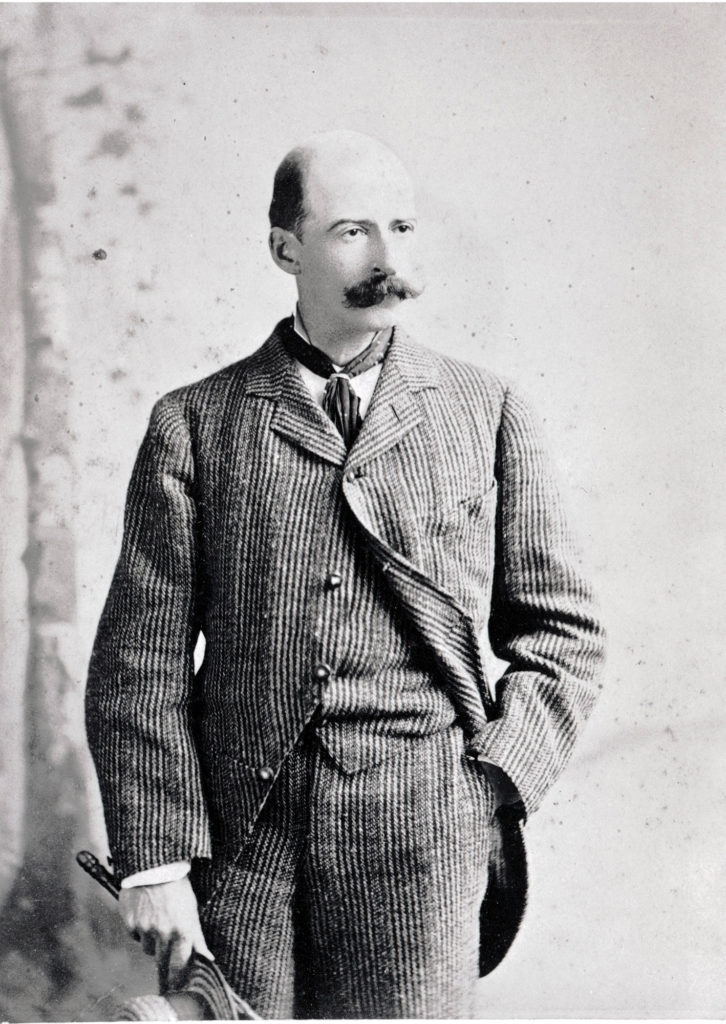

Fig. 2. Portrait of Winslow Homer by Napoleon Sarony, 1880. Albumen print, 6 by 4 1/8 inches. Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine, gift of the Homer Family.

Ruskin linked Turner’s greatness to his close study and faithful visual representation of the natural world. This was the key criterion for assessing art, Ruskin observed, and he assured readers of Modern Painters that “I shall look only for truth; bare, clear, downright statement of facts; showing in each particular, as far as I am able, what the truth of nature is.”3 He saw Turner as an exemplar of his aesthetic philosophy of “truth to nature,” a view that molded many Americans’ appreciation of painting. Indeed, this is what critics commended in the American and British works they encountered in Philadelphia: their directness and lack of affectation.

Yet, as the art historians John McCoubrey and Franklin Kelly have pointed out, American encounters with Turner’s paintings did not usually accord with expectations born of Ruskin’s text.4 One of the first public opportunities to compare the American idea of Turner to an actual canvas came at the 1872 inaugural exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where Johnston (the museum’s founding president) featured his new Turner acquisition. Slave Ship’s bold facture, curious sense of space, and vivid colors befuddled critics, who struggled to reconcile Turner’s purported aim of portraying nature accurately with the painting itself. “It is certainly an astonishing picture,” wrote a reviewer for the New York Tribune, “but it is impossible, we should think, to judge it fairly unless we . . . decline to search too curiously for demonstrations of its literal truthfulness to nature.”5 Different writers were less measured. The reviewer for Scribner’s Monthly pointed out that “the delineation shall look like the thing delineated, and act on the mind of the beholder by direct resemblance,” and Slave Ship did no such thing.6

Fig. 3. The Dinner Horn by Homer, 1873. Signed and dated “HOMER/1873” on railing at center right. Oil on canvas, 11 7/8 by 14 ½ inches. Detroit Institute of Arts / gift of Dexter M. Ferry Jr.; Bridgeman Images photograph.

A common charge leveled against Turner’s paintings and oil sketches was their “indistinctness,” a charge unlikely to have troubled Homer. As art historian Margaret C. Conrads has indicated, indistinctness was a charge frequently leveled against the artist’s work in the second half of the 1870s. Although his croquet scenes of the 1860s were celebrated for “how well the … figure is drawn,”7 critics of the 1870s took issue with his increasing tendency to create bold areas of color and light rather than carefully modeling forms. This technique also tended to flatten illusionistic perspective, emphasizing the composition’s design elements over its mimetic function, as in Homer’s In the Mountains (Fig. 6), where the four female figures are little more than dashes of color against diagonal bands of taupe, deep green, and slate blue.8 His use of color and brushwork indicate a more intuitive appreciation for Turner than that of his critics or colleagues.

Fig. 4. Croquet Scene by Homer, 1866. Signed and dated “WINSLOW HOMER/ – 66 –” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 15 7/8 by 26 1/8 inches. Art Institute of Chicago, Friends of the American Art Collection, Goodman Fund; photograph courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago / Art Resource, NY.

If American critics’ growing interest in British art—and in Turner especially—was one potential factor that influenced Homer’s decision to travel to England, the success of his Cotton Pickers (Fig. 7) may have been another. The work, one of a series he made between 1874 and 1876 depicting African-American life during Reconstruction, features two female fieldworkers carrying bushels of harvested cotton. The women, shown from a low perspective, appear monumental. The composition, enthusiastically praised as “simple, unpretentious, natural” when it was displayed at New York’s Century Club in March 1877, was bought almost immediately.9

The original purchaser, identified only as an English cotton merchant, submitted the work to the Engsummer 1878 exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts, making The Cotton Pickers the first of Homer’s paintings to be publicly displayed in Britain. Even more significant was its mention in the British artpress, one of the relatively few canvases to be so acknowledged. Notice may have been minor—the review in London’s Art Journal noted only that “there is vraisemblance also in WINSLOW HORNER’s [sic] ‘Cotton Pickers, North Carolina’”—but recognition must have been heartening nonetheless.10

Fig. 5. Slave Ship (Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On) by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), 1840. Oil on canvas, 35 3/4 by 48 1/4 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Henry Lillie Pierce Fund; photograph © 2017 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The new sense of professional possibility created by the London display of The Cotton Pickers and the growing critical interest in British art in the 1870s seem to have colluded in directing Homer’s travels. The British art world, with its preference for unpretentious subjects, simply and declaratively portrayed, would have felt familiar to Homer. At the same time, it allowed a certain stylistic flexibility: unlike American artists and critics, who generally expected finely modeled forms and a high degree of finish, the British—accustomed to a Turnerian truth to nature—could accept looser brushwork and less rigidity in the portrayal of space and volume.

Fig. 6. In the Mountains by Homer, 1877. Signed and dated “HOMER / 1877” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 23 7/8 by 38 1/8 inches. Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund.

These features would become more pronounced in Homer’s work during the nearly twenty months he spent abroad. Likely hoping to re-create the earlier success of The Cotton Pickers, he submitted to the 1882 Royal Academy exhibition his major Cullercoats oil Hark! The Lark (Fig. 1). There, however, he replaced the African-American fieldworkers with three robust village fisherwomen, and titled the composition with a quote from Shakespeare’s play about ancient British sovereignty, Cymbeline, to evoke the nation’s deep history. The painting failed to receive mention in the British art press, yet Homer would later describe it as “the most important picture I ever painted, and the very best one.”11

Fig. 7. The Cotton Pickers by Homer, 1876. Signed and dated “WINSLOW HOMER / 1876” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 by 38 1/8 inches. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, acquisition made possible through Museum Trustees.

Coming Away: Winslow Homer and England was organized by the Worcester Art Museum and the Milwaukee Art Museum and will be on view in Worcester from November 11 to February 4, 2018, and in Milwaukee from March 2 to May 10, 2018.

ELIZABETH ATHENS is the assistant curator of American art at the Worcester Art Museum. This article is adapted from her essay in the exhibition catalogue Coming Away: Winslow Homer and England.

1 S[usan] N[ichols] C[arter], “Art at the Exhibition,” Appletons’ Journal of Literature, Science, and Art, June 3, 1876, p. 724. Margaret C. Conrads has suggested the increased interest in British art after the centennial as a possible factor for Homer’s decision to travel to England in her Winslow Homer and the Critics: Forging a National Art in the 1870s (Princeton University Press in association with the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Princeton, NJ, 2001), p. 227 n. 73. 2 “The Fine Arts at the Centennial.—II,” American Architect and Building News, July 8, 1876, p. 221. This source is cited in Conrads, Winslow Homer and the Critics, p. 227 n. 73, as is “Paintings at the Centennial Exhibition. The English Pictures,” Art Journal, September 1876, pp. 218–220. 3 John Ruskin, Modern Painters, vol. 1, 4th ed. (London, 1848), p. 48. 4 John McCoubrey, “Turner’s Slave Ship: Abolition, Ruskin, and Reception,” Word & Image, vol. 14, no. 4 (October–December 1998), p. 349; and Franklin Kelly, “Turner and America,” in J. M. W. Turner, ed. Ian Warrell (Tate, London, 2007), pp. 237–238. 5 “Fine Arts—Music: Fine Arts. ‘The Slave Ship,’ by J. M. W. Turner,” New York Tribune, April 10, 1872, p. 5. 6 “Culture and Progress: Turner’s ‘Slave Ship,’” Scribner’s Monthly, vol. 4, no. 2 (June 1872), p. 250. 7 “Fine Arts: Pictures Elsewhere,” Nation, vol. 3 (November 15, 1866); pp. 395–396. 8 Conrads, Winslow Homer and the Critics, pp. 79–84. 9 “Winslow Homer’s ‘Cotton Pickers,’” New York Evening Post, March 30, 1877, cited in Lloyd Goodrich, Record of Works by Winslow Homer, ed. and expanded by Abigail Booth Gerdts, vol. 3 (Spanierman Gallery: Goodrich-Homer Art Education Project, New York, 2008), p. 415. 10 “The Royal Academy Exhibition,” Art Journal, July 1878, p. 145. 11 Winslow Homer to O’Brien and Son, March 20, 1902, O’Brien Galleries records, 1811–1970, Archives of American Art, Washington, DC, reproduced in William Howe Downes, The Life and Works of Winslow Homer (Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, 1911), p. 149.