As public usage and demand for weathervanes waned in the second and third decades of the twentieth century, a handful of pioneering folk art advocates began to seek and exhibit old weathervanes, which, they realized, represented America’s first and most broadly representative sculptural tradition, and, more importantly, deserved recognition as significant works of American art. Among these early connoisseurs were the modernist sculptor Elie Nadelman (1882–1946), who, with his wife, Viola, amassed a collection of nearly fifteen thousand pieces of American and European folk art and founded a private Museum of Folk and Peasant Arts outside their home in the Bronx in 1926; the legendary American art dealer Edith Halpert (1900–1970), who began offering folk art in her Downtown Gallery in Greenwich Village in the late 1920s; and curator, writer, and arts administrator Holger Cahill (1887–1960), who mounted the first exhibition of what he called “American folk sculpture” at the Newark Museum in 1931.

Perhaps not coincidentally, all three were immigrants, and, during a time when American museums were focused squarely on European art, their fresh eyes led them to become passionately committed to American folk and modernist art. Nadelman was born in Warsaw, the seventh child of an urbane jeweler who supported his son’s early interest in art and culture. After spending two years in Germany, Nadelman moved to Paris in 1904, where he studied and found moderate success. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, he came to New York, where he settled in the Riverdale section of the Bronx and lived there the rest of his life.

Nadelman was particularly drawn to three dimensional folk objects, which formed a large portion of his collection. These handmade pieces also profoundly influenced his art, which consisted largely of stylized human and animal figures. Unfortunately, Viola Nadelman lost much of her inherited fortune during the Depression, and the couple ultimately sold their collection to the New-York Historical Society in 1937. Both the Nadelmans’ collection and Elie Nadelman’s own sculpture, which has consistently grown in critical stature since his death, have in turn influenced appreciation of folk art to the present day, most recently through a 2016 exhibition at the New-York Historical Society.1

Edith Halpert was born Ginda Gregoryevna Fivoosiovitch in Odessa, then part of the Russian Empire, and, like hundreds of thousands of other Jews, fled persecution in Russia, arriving in New York with her mother and sister in 1906. As a teenager with the Americanized name Edith Gregor, she became involved in the fledgling modernist art movement in New York; she studied painting for a time, joined artist groups, sought the company of modernist artists, and, when she was seventeen, fell in love with a struggling painter named Sam Halpert, who was nearly twice her age. They married a year later. She soon realized that she would have to be the breadwinner, and, after first landing a good-paying job as an efficiency expert for an investment bank, she ultimately decided to plunge back into the art world and open a gallery in New York, which she did in the fall of 1926. Even though there was still little interest in American art of any kind, and the Eurocentric Metropolitan Museum of Art was the only art museum in the city, she saw an opportunity. It was a wide open if dicey time, and Halpert became a leading force in bringing modern American art to the fore.

Like Halpert, Holger Cahill was an outsider who reinvented himself in New York. He was born Sveinn Kristjan Bjarnarson in Iceland, but his dirt-poor, homesteading family brought him first to Canada and then to North Dakota. He ran away from a troubled home and eventually wound up in New York City, where he studied journalism. Eddie, as he was known to his friends, began working as a publicist for the Newark Museum in 1922 and quickly rose to become the museum’s curator.

He met Halpert in Ogunquit, Maine, in 1926, where a number of young modernist artists, including Robert Laurent, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and William Zorach, summered. Cahill and the Ogunquit artists were drawn to the largely unappreciated folk art paintings and sculpture they found in local shops and homes, both for aesthetic reasons and because they saw intuitive connections between the art they were creating and the strong colors, crisp lines, and direct honesty of what was soon called American folk art.2 Cahill convinced Halpert that folk art was the true ancestor of the modernist art she was selling, and that she could make money selling it too. So, in 1929, the two began a partnership in what they called the American Folk Art Gallery, an adjunct of the Downtown Gallery.

In his introduction to the catalogue for the Newark show of folk sculpture, Cahill made the case for the works in the exhibition this way: “It [folk sculpture] is never the product of art movements, but comes out of craft traditions, plus that personal something of the rare craftsman who is an artist by nature if not by training. This art is based not on measurements or calculations but on feeling, and it rarely fits in with the standards of realism. It goes straight to the fundamentals of art—rhythm, design, balance, proportion, which the folk artist feels instinctively.”3

The year following his American folk sculpture exhibition, Cahill was appointed acting director of the Museum of Modern Art, where he organized the trailblazing exhibition American Folk Art: Art of the Common Man in America, drawn almost exclusively from Abby Aldrich Rockefeller’s collection. From 1935 to 1943, he served as national director of the WPA’s Federal Art Project. Under that aegis, he supervised the creation of the Index of American Design, which employed hundreds of artists across the country to record the widest possible variety of American vernacular art and traditional design motifs, including weathervanes.

Although Halpert is best known today for showcasing the work of such major American artists as Stuart Davis, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Jacob Lawrence, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Charles Sheeler, she continued to champion folk art throughout her long career. Weathervanes were always part of her inventory, and she and her agents traveled throughout Pennsylvania, upstate New York, and New England for appealing vanes. During the 1940s and ’50s, Halpert’s most reliable and enthusiastic folk sculpture client was Electra Havemeyer Webb (1888–1960), who founded the Shelburne Museum in 1947, and, along with many other pieces of three-dimensional folk art, bought thirty-one of the Downtown Gallery’s vanes.

In the fall of 1954, Time magazine publicized a new Halpert venture: “Halpert knew that some of the old iron [weathervane] molds must still be around. She searched for ten years up and down New England, [and] finally, last year, found a jumble of 350 Gushing [sic] molds in the yard of a Chelsea (Mass.) junkman. Last week in New York’s Associated American Artists Galleries, sixteen new vanes shaped from the old molds were on exhibition. Considering that they were meant to be seen atop a high perch, the figures were remarkably graceful close up.”4

The venture was not a financial success, and many of Halpert’s replicas of L. W. Cushing and Sons’ vanes were sold to dealers at discounted prices and their copper surfaces artificially patinated or covered with new gold leaf to make them more attractive to buyers. Her three-hundred-odd Cushing replicas occasionally turn up in the marketplace.

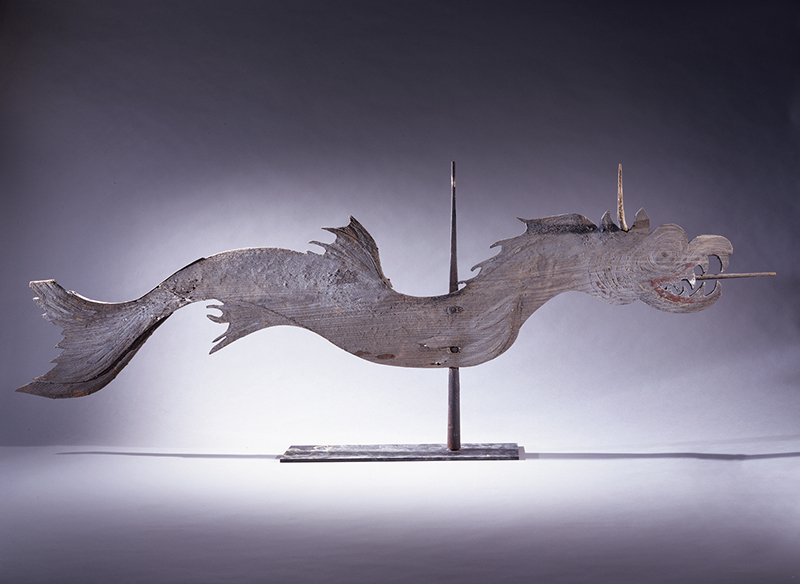

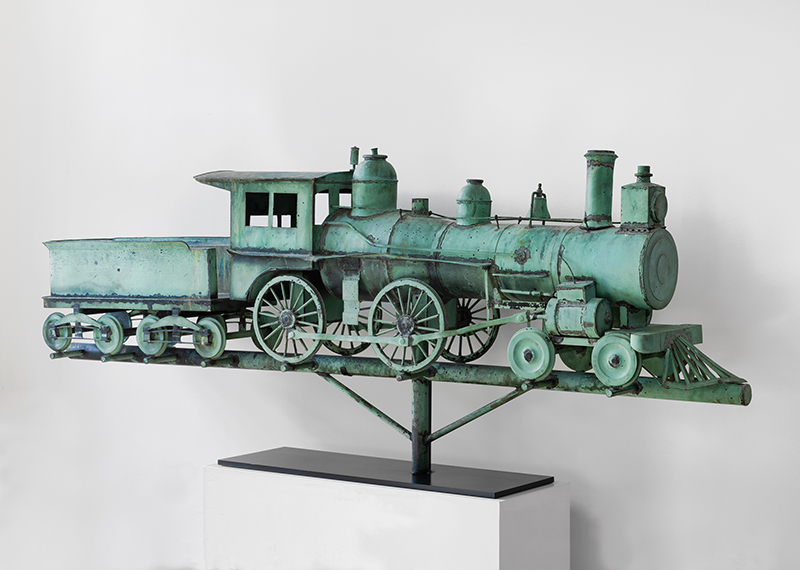

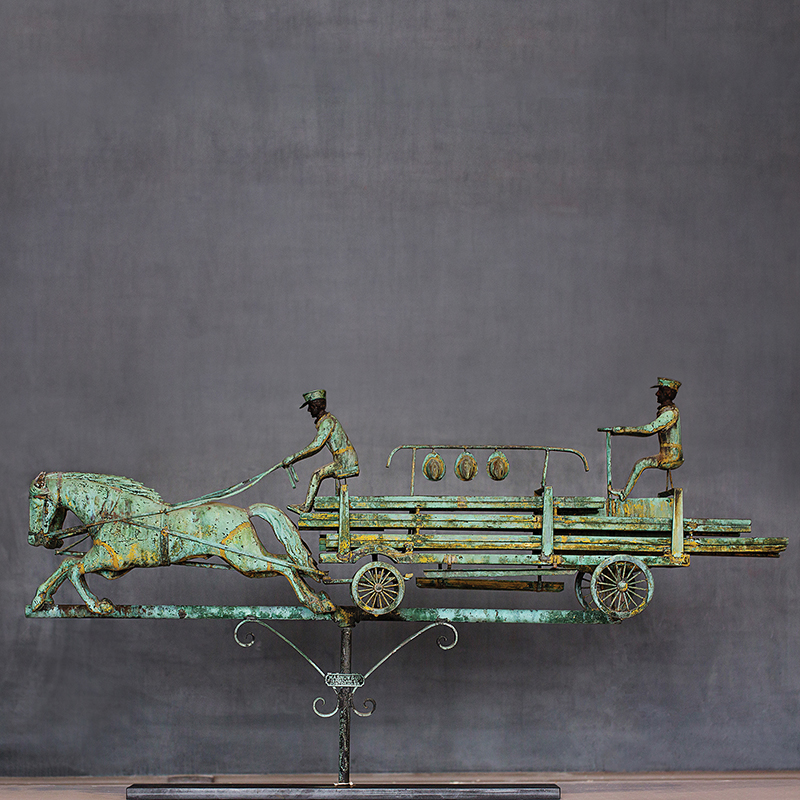

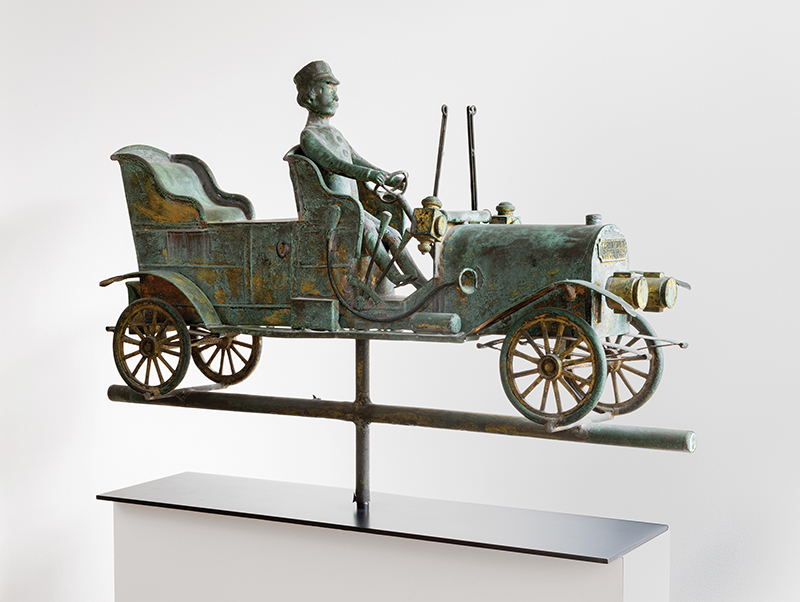

Another key exponent of folk sculpture was Adele Earnest (1901–1993), who sought out Halpert in the early 1930s. In 1943, after years of supplying Pennsylvania pickings to the legendary dealer, Earnest became a competitor when she and her neighbor Cordelia Hamilton founded the Stony Point Folk Art Gallery in Stony Point, New York, some forty miles up the Hudson River from New York City. Unlike Halpert, Earnest’s focus was always squarely on handcrafted, three-dimensional objects, especially weathervanes and bird decoys. During the war years, she and Hamilton ventured northward on numerous “scouting trips” across upstate New York and New England in search of weathervanes. In her memoir, she recalled: “The more we asked and looked for vanes, the more we realized the fascinating varieties, the myriad shapes, media, techniques and subject matter. The weathervane recorded history as well as the way of the wind . . . The weathervane is one of the earliest of our arts. The pioneer settler . . . was eager to set the brand of his own hand upon his church, his barn, his shop. He fashioned . . . the wind bar not only to indicate the current of his time but to herald his independence.”5

Earnest was born in Waltham, Massachusetts, and the first vane she bought was a jumping steeplechase horse she attributed to the Waltham manufacturer A. L. Jewell.6 She paid twenty-eight dollars for it. Her ambition grew apace with her passion and knowledge. In 1952, with the help of sculptor David Smith, she and Hamilton began mounting shows of folk sculpture at the prestigious Willard Gallery in Manhattan, which represented Smith and other contemporary sculptors. Their shows at the Willard Gallery put them in touch with such leading folk art collectors as Stephen Clark, Stewart Gregory, Herbert Waide Hemphill Jr., Maxim Karolik, Jean and Howard Lipman, Alastair Bradley Martin, Joseph B. “Burt” Martinson, and Electra Webb.

Earnest and Hamilton upped the ante by organizing a comprehensive exhibition of folk sculpture that in 1954 and ’55 traveled to major art museums in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Santa Fe, Dallas, and Tulsa. While they continued to mount biennial exhibitions at the Willard Gallery throughout the 1950s, they came to believe that folk art needed an institutional home in New York, the center of America’s cultural world. In 1961, they gathered a small group of like-minded colleagues, including Burt Martinson, Bert Hemphill, and Willard Gallery owner Marian Willard Johnson, and founded the Museum of Early American Folk Arts, now the American Folk Art Museum. Earnest remained steadfastly dedicated to the new museum, offering financial support and donating significant objects to its growing collections, most notably a painted sheet-iron Archangel Gabriel weathervane that became the museum’s symbol.

Jean Lipman was not just a folk art collector but also a wide-ranging art historian and author and the longtime editor of the magazine Art in America. She was particularly interested in sculpture and, in 1948, published American Folk Art in Wood, Metal and Stone, which studied ship figureheads, weathervanes, cigar store figures, circus and carousel carvings, decoys, toys, and decorative house and garden sculpture. Lipman was a strong proponent of modern art who freely compared folk and contemporary works. Writing about wooden silhouette weathervanes by Maine carver James Lombard, she observed: “The effect through a flair for functional design and a natural vitality of execution, as seen in these provincial weathervanes, would be hard to surpass in the most finished pieces of academic sculpture.”7

In 1974, Lipman and Alice Winchester, the editor of The Magazine ANTIQUES, cocurated the influential exhibition The Flowering of American Folk Art, 1776–1876 at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The exhibition, which included seventeen weathervanes among its 409 objects, was the most comprehensive folk art show that had ever been mounted, and it fostered a resurgence of interest in folk art during the Bicentennial.

In 1975, Myrna Kaye, a prolific researcher, educator, writer, and adjunct lecturer at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, published the seminal study Yankee Weathervanes. The book offered the first deeply researched look at the history and art of American weathervanes, from the late 1600s to the present day. Kaye characterized her book as a social history of an “all-too neglected art. In telling its story, I tell the story of people . . . people who made vanes and bought them, observed them and preserved them.”8 The landmark Sotheby Parke Bernet sale of Stewart Gregory’s folk art collection in 1979 marked the real start of an ongoing growth of interest in collecting folk art. The top lot in the Gregory sale was a portrait of a child by the deaf itinerant artist John Brewster Jr., which brought a then-astonishing $67,500. A weathervane of a standing Native American figure drawing his bow, made around 1870 and found in Pomfret, Connecticut, sold for $25,000, another price that shattered previous records and stunned the antiques world.9

Appreciation of outstanding vanes as significant works of art continued to grow throughout the 1980s and sometimes came from surprising sources. Discussing a drawing of a rooster in a review of a 1981 exhibition of Picasso’s work, John Russell, chief art critic for the New York Times, noted that Picasso “once said to his fellow-painter Xavier Gonzales, that some of the best roosters were the ones on American weathervanes.”10 By 1983, weathervanes had become such a symbol of America that the British art magazine Connoisseur announced it was moving to the US with a fullpage photo of its new editor-in-chief, former Metropolitan Museum of Art director Thomas Hoving, admiring a spread-winged American eagle weathervane borrowed from the Madison Avenue folk art gallery America Hurrah!

Over the past thirty years, weathervanes have ranked with paintings as the most valuable and sought-after form of American folk art. In 1990, the top lot in the posthumous auction of Creative Playthings founder Bernard M. Barenholtz’s folk art collection was a magisterial circa-1860 horse and rider by J. Howard and Co. of West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, which sold for $770,000.11 Since that groundbreaking event, a handful of other prime examples have sold for more than a million dollars, topped by a circa-1900 J. L. Mott vane of a five-foot-two-inch-tall Native American figure lifting his bow and arrow skyward, which garnered $5.8 million at Sotheby’s in October 2006.

As prices surged, connoisseurship increased and new standards of excellence developed. Like Americana collectors of all stripes, today’s weathervane collectors not only consider a piece’s form, rarity, and provenance, but also pay close attention to its condition, seeking an original and largely unaltered structure with a richly patinated surface that reflects the history of the object’s use over its lifetime. Unlike original vane makers and their customers, they do not want brightly gilded or painted surfaces that look brand new, preferring instead a weathered, variegated surface that can only be created over years of rooftop exposure to wind, dirt, sun, and precipitation. Copper, in particular, slowly takes on a complex and often beautiful mixture of verdigris and remnants of gilding, sizing, and/or paint that is highly prized by contemporary collectors. The same form with and without that sort of patina can differ vastly in aesthetic and monetary value.

Money, of course, does not necessarily equate with artistic merit. But the best American weathervanes rank among this country’s most remarkable works of sculptural art. Vanes are highly accessible manifestations of American imagination, craftsmanship, and artistry. They were intended for prominent outdoor public display, and they represent the rich, democratic mix of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Americans’ vocations and avocations, toil and pleasures, financial pursuits and recreations. In their eclectic range of forms and intentions, American vanes embody this country’s spirit and humor, its personal and civic pride, its common values and aspirations, its hopes and dreams, as well as any other art produced on these shores.

American Weathervanes: The Art of the Winds is on view at the American Folk Art Museum to January 2, 2022. This article is an adaptation of the first chapter of the accompanying book of the same title, which is published by Rizzoli.

1 The Folk Art Collection of Elie and Viola Nadelman, New York Historical Society, May 20–August 21, 2016. 2 For further discussion of the origins of American folk art as a collecting category, see Elizabeth Stillinger, A Kind of Archeology: Collecting American Folk Art, 1876– 1976 (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011). 3 Holger Cahill, “American Folk Sculpture,” in Elinor Robinson Bradshaw, American Folk Sculpture: The Work of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Craftsmen (Newark, NJ: Newark Museum, 1931), p. 13. 4 “Art: The Useful and Agreeable,” Time, September 27, 1954, at timecontent .com.5 Adele Earnest, Folk Art in America: A Personal View (Exton, PA: Schiffer, 1984), pp. 36, 83. 6 Later scholarship has determined that Earnest’s jumping steeplechase horse was not made by A. L. Jewell. 7 Jean Lipman, American Folk Art in Wood, Metal and Stone (New York: Pantheon Books, 1948), p. 51. 8 Myrna Kaye, Yankee Weathervanes (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1975), dust jacket. 9 Important American Folk Art and Furniture: The Distinguished Collection of the Late Stewart E. Gregory, Wilton, Connecticut, Sotheby Parke Bernet, New York, January 27, 1979, lot 207. 10 John Russell, “A Celebration of Picasso as Draftsman,” New York Times, August 2, 1981, section 2, p. 25. 11 Important American Folk Art from the Collection of the Late Bernard M. Barenholtz, Sotheby’s, New York, January 27, 1990, lot 1515.

ROBERT SHAW is an independent curator and art historian who has written and lectured extensively on many aspects of American folk art. His many books include American Quilts: The Democratic Art. In addition to the weathervane exhibition at the American Folk Art Museum, he also has curated exhibitions at the Dallas Museum of Natural History, the National Gallery of Art, the Fenimore Art Museum, and the Shelburne Museum, where he served as curator from 1981 to 1994.