It might seem odd, even profane, to encounter the works of Walt Disney in that temple of high culture, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And yet, Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts persuasively argues that the linkage is stronger than one might suppose. As early as 1938, some of the animator’s storyboards had entered the Met’s collection, and four years later the augustly highminded Museum of Modern Art devoted an entire exhibition to Bambi.

In mounting this illuminating show, Wolf Burchard, the curator, has posed (and answered) an inspired question. Despite more recent attempts to expand Disney’s cultural reach (for example, Moana, from every animation frame to issue from the Disney studios seems to be populated with artifacts of the European past, from Gothic castles and Renaissance palaces to rococo interiors and attire? In the animistic worldview that has always reigned at Disney, everything that exists is in movement and so is part of the same cosmic dance, whether teapots and candelabras, or sofas and long-case clocks, not to mention squirrels and hummingbirds. Architecture, either drawn on celluloid or reified in theme parks, is as apt to invoke the Chambord Palace of François I as it is the Versailles of Louis XIV. This surfeit of European artifacts has been part of Disney’s formula for success since the very beginning.

But other than our intuitive sense of the general Europeanness of Disney cartoons, we rarely ask where all those trappings came from— where Disney and his successors found them. This question, the focus of the present show, is important: nearly everyone alive has encountered Disney’s animation in early childhood and so has carried into adulthood something, however vague, of the formal implications of those films. Especially outside of Europe itself, the animation created by Disney, his successors, and his imitators has played an important role in shaping that vaporous totality of colors and forms that make up how we conceive of the European past. Splendid examples of these artifacts, many from the Met’s own collection of decorative arts, figure among the nearly two hundred objects, paintings, documents, and storyboards included in the exhibition.

Fig. 5. Teapot with cover, Meissen manufactory, with decoration attributed to the Aufenwerth workshop, German, c. 1719–1730. Hard-paste porcelain decorated in polychrome enamels and gold, with metal chain and mounts; height 6 1/8, width 6 7/8, depth 3 7/8 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Irwin Untermyer.

Nothing in Walt Disney’s background would have prepared us for the robust Eurocentrism that defines his art and that of his movie studio. Born in Chicago in 1901 and raised in Kansas City, Disney first encountered Europe when he was seventeen years old.

Having altered his birth certificate so that he could serve in the Great War, he found himself in France, driving an ambulance for the Red Cross. By the time he returned to the Continent in 1935, now with his young family, he was already an international celebrity who was lionized wherever he went. On that occasion, and on many subsequent trips, Disney raided the local bookstores to amass a library of books and images related to the fine and decorative arts, and to heraldry and royal costumes. In the days before the internet, these sources would provide his draftsmen and colorists with the essential tools to body forth the historicist reveries that make up his films.

By emphasizing French decorative arts, the subtitle of the Met exhibition gets directly to the point: a great deal of Disney’s aesthetics derives, powerfully and repeatedly, from French culture of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, but perhaps most of all from the rococo. And while the diminutive porcelain figures from Meissen, in Saxony, also influenced Disney, as the show acknowledges, they embody a specific eighteenth-century German interpretation of contemporary French taste (Fig. 15).

In part, this Gallic focus was to be expected, since many of the stories that inspired Disney and his army of animators, from Sleeping Beauty and Snow White to Cinderella and Beauty and the Beast, were based on the writings of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French authors, among them Charles Perrault and Gabrielle de Villeneuve. Even Aladdin, although ultimately of Middle Eastern derivation, is based on an early eighteenth-century French text by Antoine Galland.

A distinction should be drawn, however, between Disney’s visual tactics, which are indeed inspired by French decorative art, and his grand visual strategy, which is largely an amalgam of the symbolist, expressionist, and surrealist styles. That is to say that French decorative and architectural forms are invoked and transformed within a visual context that—like most cartoons, from the New Yorker’s to those of children’s television—owes more to modernism than to anything else.

In theory, there was nothing to stop the studio from presenting Beauty and the Beast in the aesthetics of the eighteenth-century illustrator Moreau l’Aîné or even Fragonard, rather as Loving Vincent, a recent animated life of Van Gogh, stunningly reenacts the look and composition of his paintings. Instead, modernism has always been the defining formal element of Disney and his studio— a distinction one must make, since, even while he was alive, the animation of his films, from composition to color and drawing, was entirely carried out by others.

Thus, Robert E. Stanton’s background painting for the library in Beauty and the Beast (1991), with its cool blues and the steep tilt of its towering shelves, recalls the exorbitances of expressionist painting and cinema. We find a similar spatial daring in Mary Blair’s concept art for Cinderella (Fig. 13), even though, here, the heroine gazes into an oversized rococo mirror set in a refined domestic interior that comically evokes the intimisme of a Pierre Bonnard painting. A very different aesthetic informs the balanced, symmetrical compositions that Eyvind Earle conceived for Sleeping Beauty (Fig. 10), in which the unmistakable modernity of the coloring and draftsmanship unites the symbolism of Puvis de Chavannes with a hint of the sixteenth-century Antwerp mannerists.

Fig. 12. Concept art for Beauty and the Beast by Hall, 1989. Signed and dated “Peter J. Hall/ ’89” at lower right. Watercolor, marker, and graphite on paper, 18 by 23 7/8 inches. Walt Disney Animation Research Library, © Disney.

Fig. 13. Concept art for Cinderella (1950), c. 1948. Gouache, graphite, and pastel on board, 12 by 10 inches. Walt Disney Animation Research Library, © Disney.

But perhaps the most essential visual element of Disney’s films is their irreducible Americanness. Americans are apt to seem most American when they pay tribute to Europe, as so many of the Disney films do. What jazz—certainly in its origins—is to music, the Disney style—certainly in its mid-century manifestations—is to representations of the visible world: populist and fun and, in its schematic liberties, almost impishly irreverent. To many Americans, especially those of Disney’s generation, Europe stood out as the land of manners, of stiff, even stilted ceremony. By contrast, many Americans—and I suspect Disney was one of them—have long seen their own country as standing in opposition to that formality, as being a land of unbridled modernity. As the Met exhibition proves, however, such notions are by no means incompatible with a deep interest in the European past and an abiding respect.

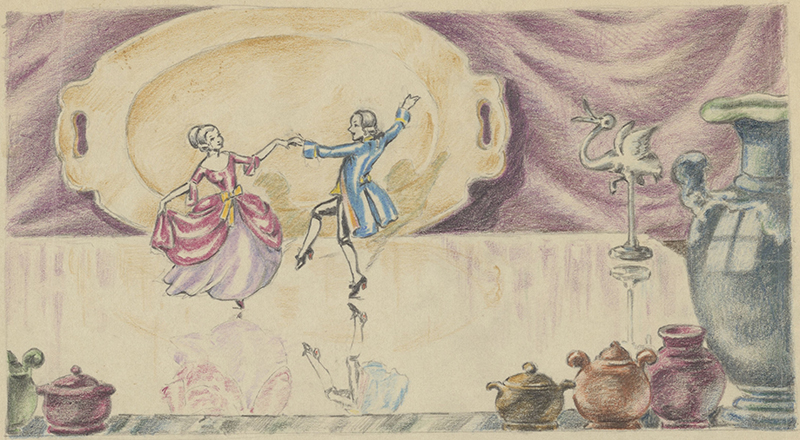

Fig. 14. Story sketch for The China Shop (1934), c. 1933. Colored pencil and graphite on paper, 6 by 8 inches. Walt Disney Animation Research Library, © Disney.

Fig. 15. Faustina Bordoni and Fox by Johann Joachim Kändler (1706–1775), Meissen manufactory, c. 1743. Hard-paste porcelain; height 6, width 11, depth 6 3/4 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Untermyer gift.

Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art until March 6.