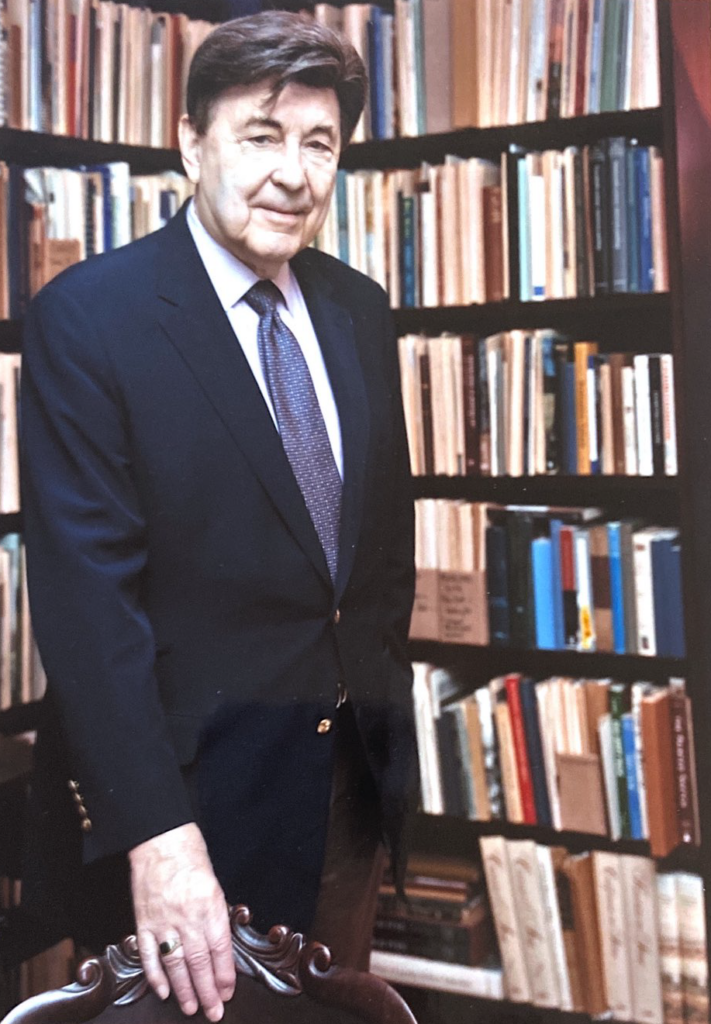

The great historian of American art William H. Gerdts died on April 14, 2020 at the age of 91 from complications of Covid-19 at White Plains Hospital in Westchester County, New York. Over a remarkable career spanning more than sixty years as a scholar and curator, Bill (as friends, colleagues, and students all called him) created a prodigious body of writing on American art. His sweep was magisterial historically—he traversed the late seventeenth century through the early twentieth—and geographically. No corner of the nation escaped him. Bill’s knowledge of American art, at once encyclopedic and intimate, was built over the many years of his long career but was most dramatically manifested in the 1990 publication of his three- volume Art Across America: Two Centuries of Regional Painting, 1710-1920 by Abbeville Press in New York. It was 210 years of painting in a comprehensive context beyond the ambition, let alone imagining, of all but very few art historians.

And though Bill’s aesthetic home was built within the property lines of the eighteenth through early twentieth centuries, he was unafraid to venture beyond them. In the 1960s, he curated exhibitions of contemporary figurative and still life painting for the American Federation of Arts and the Museum of Modern Art and in recent years wrote insightfully on the work of contemporary realists Stephen Scott Young and Jacob Collins.

Still, the earlier eras were his richest province. From 1955 to 1968, Bill frequently contributed to The Magazine ANTIQUES. For its pages, he wrote articles on the art of Henry Inman, Thomas Birch, Chauncey Bradley Ives, Paul Lacroix, and Thomas Moran, as well as on the private collections of James H. Ricau, Henry Fuller, and Roderick H. D. Henderson. He wrote on nineteenth-century American still life painting and sculpture and had a unique interest in Egyptian motifs in nineteenth-century American painting. His ANTIQUESarticle on that highly specialized subject evolved from his fascination with Egyptology, which developed while he was an art history graduate student at Harvard University, beginning in 1949. From that institution, he received a master’s degree in 1950 and a PhD in 1966.

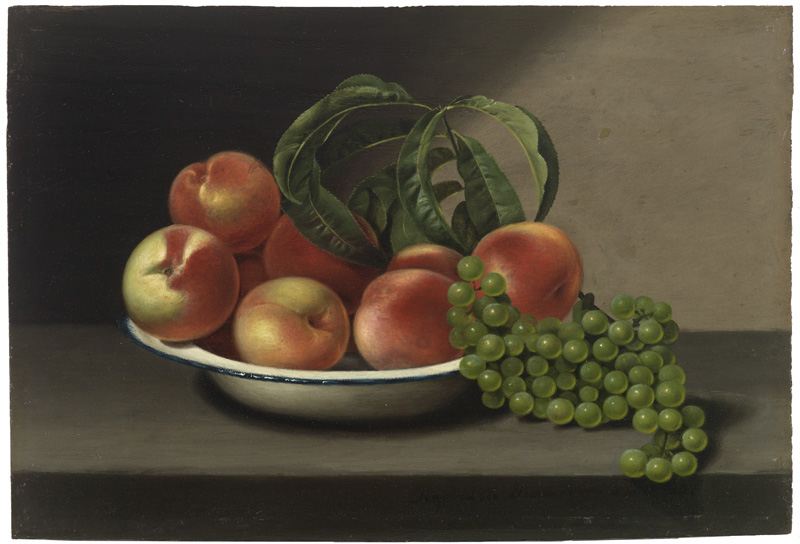

Bill was an undergraduate at Amherst College, where he conceived his interest in early American art. A story he loved to recount was of how, while working a temporary job assisting in the cataloging of Amherst’s Mead Art Museum, he discovered a miniature by James Peale—in the locked drawer of an eighteenth-century shaving cabinet! From the very beginning, Bill was more than a compiler of catalogs. He was an explorer. Indeed, while working his student job at the Mead, he made a trip into New York to see the art dealer Victor Spark. His expedition led to the Mead’s acquisition of the magnificent Still Life with Fox Grapes and Peaches (FIG. 2) by James’s uncle Raphaelle Peale.

After Harvard, Bill served as Curator of Art at the Norfolk Museum of Arts and Sciences (now the Chrysler Museum of Art), a tenure, he wryly recalled, lasting a year and fifteen days before he became Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture at the Newark Museum (today the Newark Museum of Art), not far from Jersey City, New Jersey, where he was born in 1929. At Newark, from 1954 to 1966, he was instrumental in crafting and enlarging one of the finest institutional collections of American art in the country. Among his major acquisitions were Frederic Edwin Church’s Twilight, Short Arbiter, “Twixt Day and Night” (FIG. 3), Thomas Cole’s Arch of Nero (FIG. 4), and William Henry Rinehart’s marble Leander (FIG. 5).

Bill was vigorous in his efforts to draw well-deserved attention to his museum, organizing numerous exhibitions, including Nature’s Bounty & Man’s Delight: American 19th-Century Still-life Painting (1958), Classical America, 1815-1845 (1963, co-curated with decorative arts curator Berry B. Tracy), and Women Artists of America, 1764-1965. Organized in 1965, it wasthe first museum exhibition devoted to the history of American women artists. In 1972, he collaborated with Nicolai Cilovsky, Jr. on another breakthrough, The White, Marmoreum Flock: Nineteenth Century American Women Neoclassical Sculptors, at the Vassar College Art Gallery.

Through the 1950s, Bill began to form a significant private collection of American still life painting (FIGS. 6-8). Art historian Abigail Booth Gerdts, Bill’s wife and colleague of 43 years, later joined him in this pursuit. The collection focused primarily on fruit still lifes of the nineteenth century but also included more varied subjects and later examples, in addition to sculpture, drawings, prints, and a group of history paintings by Emanuel Leutze as well as a collection of illustrated books. In 1998, a selection of more than 90 works from the collection was exhibited at the Mead Art Museum and at Berry-Hill Galleries in New York, where I was Director of Research and Exhibitions. For Beauty and for Truth: The William and Abigail Gerdts Collection of American Still Life (Amherst College, 1998), the catalog for which I wrote entries with curator Susan Danly,features an essay by Bill on the development and evolution of the collection.

Bill’s passion for collecting art was also the basis for his essays in B. Nichols Clark’s A Marble Quarry: The James H. Ricau Collection of Sculpture at the Chrysler Museum of Art (Hudson Hills Press, 1997) and A Lifetime of Collecting: Selections from the William & Abigail Gerdts Collection of American Still-Life Painting (Godel & Company Fine Art, 2017).

Like all truly great collectors, Bill and Abbie were also generous donors. They gifted to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. hundreds of works, along with their incomparable library devoted to American art. In response to my query about the extent of the donation, the National Gallery’s Deputy Director and Chief Curator, Franklin Kelly, replied:

“Starting in 2001, with the gift of a still life by Sanford Gifford, and continuing through 2018, Bill and Abbie donated some 350 works representing all areas of their collection to the National Gallery of Art in Washington. Of special importance were 35 still life’s, including works by artists such as Hannah Brown Skeele, Andrew John Henry Way, Robert Spear Dunning, and Lilly Martin Spencer, none of whom were previously represented in the Gallery’s collections. Also included were superb works on paper, such as John Henry Hill’s watercolor masterpiece, Golden Robin (Northern Oriole), (1866), sculptures such as Harriet Goodhue Hosmer’s Puck (c. 1856), rare and choice illustrated volumes such as Celia Thaxter’s Idyls and Pastorals, (1894, with illustrations by Childe Hassam) and a remarkable group of comic books, including titles by Robert Crumb and Frank Frazetta.

It is safe to say that the Gerdts collection is the most diverse and multi-faceted single collection of American art ever donated to the Gallery. Also, of inestimable importance was the Gerdts’ gift to the Gallery of their entire research library on American art. This extraordinary collection of books, catalogues, ephemera, artist files, and other rarities was generously made available by the Gerdts to countless students of the field over the years, and was of seminal importance to the development and advancement of scholarship in the field. In combination with the Gallery’s existing holdings, the Gerdts collection has formed one of the most important concentrations of resources on American art anywhere.”

After Bill left the Newark Museum in 1966, he served as an associate professor of art history and gallery director at the University of Maryland, College Park. During his three years at the helm of that gallery, he oversaw the organization of important exhibitions devoted to Jasper Cropsey, Thomas Couture, and Arthur Dove. In 1969, he moved to Coe Kerr Gallery in New York, as Vice President of Research. Three years later, he joined the faculty of the newly created City University of New York Graduate Program in Art History, where he taught until he was named Professor Emeritus in 1999.

During his early years at the CUNY Graduate Center, Bill also taught in the art history department of Brooklyn College. My own relationship with him began there in the spring of 1972 when I attended his survey class in American art history. Woefully ignorant of early American art, I had a startling aesthetic awakening in Bill’s very first class of the semester, as he introduced the projected images of the late seventeenth-century portraits of John and Elizabeth Clarke Freake by the anonymous “Freake Limner,” in the collection of the Worcester Art Museum. I was smitten, drawn in by Bill’s knowledge, enthusiasm, and love for the art he was discussing—and, equally, by his evident passion for introducing borough kids like myself to the art of our nation. I learned later that, although he was a Jersey City native, Bill had spent many of his growing-up years in Jackson Heights, Queens, and attended Newtown High School in nearby Elmhurst.

Soon after that first class, I decided I wanted to specialize in the study of American art. A little later, a fellow Brooklyn College student, who was friendly with Bill, told him about my burgeoning interest in early American art. With this, a mentorship and close friendship began, which endured until Bill’s death on April 14 of this year.

I followed Bill from Brooklyn College to the Graduate Center, where he taught and worked closely with generations of students who have gone on to successful careers in museums, universities, galleries, and independently. While we were still at Brooklyn College, Bill encouraged me to write a paper on the late nineteenth-century artist Robert Frederick Blum. I did that, and, later, at the Graduate Center, I wrote my doctoral dissertation on Blum—under Bill’s direction. Until the very end of his life, Bill Gerdts was always generously and genuinely interested in my efforts. Shortly before the COVID crisis, he read and commented on a catalog essay I wrote for an exhibition that was opening at the Woodstock Artists Association.

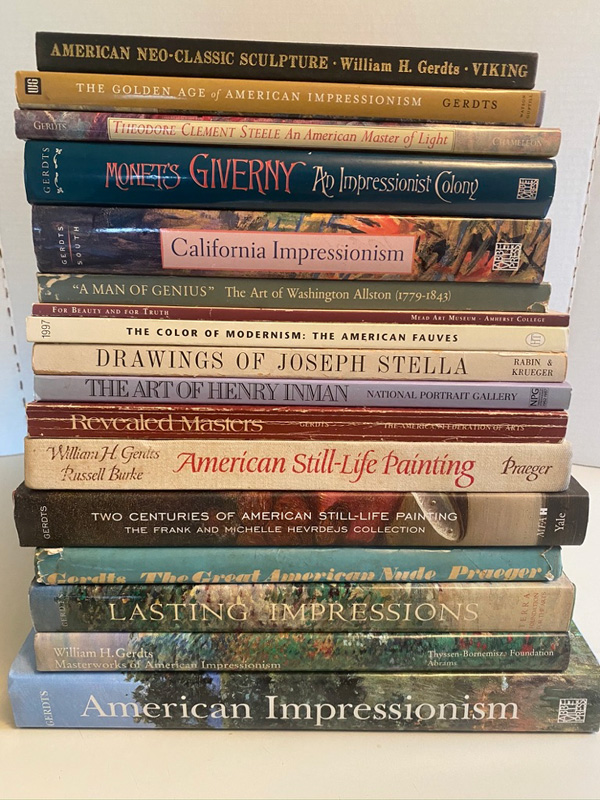

Bill’s gifts as a teacher and mentor were one with his gifts as a writer. Whether teaching or writing, he wielded a powerful genius for encapsulating and expanding upon key moments in the unfolding story of American art and pointing out fresh ways of looking and thinking about that story. He delved—and deeply, too—into a remarkable range of areas (FIG. 9), from still life, portraiture, landscape, genre, and history painting and sculpture, to topics that ranged in time and style from the impact of the early nineteenth-century German romantic classicists in Rome on Washington Allston (Arts Quarterly, summer 1969) to the impact of Henri Matisse and the French Fauves on early twentieth-century American painting (The Color of Modernism: The American Fauves, Hollis Taggart Galleries, New York).

He was the recognized authority on American still life painting, American Neo-classical sculpture, and American Impressionism. In 1980 he curated a major exhibition on American Impressionism for the Henry Art Gallery at the University of Washington in Seattle, a project that led to the publication in 1984 of the landmark American Impressionism by Abbeville Press. That masterwork spawned a series of publications and exhibitions, including California Impressionism (written with his former student Will South, published by Abbeville Press in 1988); Masterworks of American Impressionism (Thyssen-Bornemisza Foundation in association with an exhibition at the Villa Favorita, Thyssen-Bornemisza, Lugano-Castagnola, 1991); Lasting Impressions: American Painters in France, 1865-1915 (for the Terra Foundation for the Arts in association with an exhibition at the Musée Americain in Giverny, France, 1992); Monet’s Giverny: An American Impressionist Colony (Abbeville Press, 1993); Impressionist New York (Abbeville Press, 1994); and The Golden Age of American Impressionism (Watson-Guptill Publishers in association with an exhibition of the same title at the Heckscher Museum, 2003). Bill also delivered scores of lectures on American Impressionism and a multitude of other subjects at museums and other institutions across the country.

Over his career, Bill championed an incredible range of artists, among them Washington Allston, Henry Inman, John Singer Sargent, Childe Hassam, and William Glackens as well as such lesser known figures as Theodore Clement Steele, Alice Schille, Theodore Wores, Colin Campbell Cooper, Mathias J. Alten, Dawson Dawson Watson, Leon Dabo, and William Blair Bruce. One of my favorite Bill Gerdts publications is the catalog Revealed Masters: 19th Century American Art, which accompanied an exhibition that he curated in 1974 for the American Federation of Arts focusing on American artists he felt demanded a closer look. His catalog essay explored multiple and disparate areas of inquiry, among them the origins of American still life, the work of mid-century expatriate artists, Romanticism and the tropics, prototypes in genre fiction, and American painters abroad.

●

To return now to a more personal note, it was through Bill that I came to know and even become friendly with a number of his many, many wonderful friends and associates in the field of American art. Among these was the art historian Percy North, who was Bill’s student at the University of Maryland. When I wrote to her about their travels and friendship, she responded by email:

“Bill had been an inveterate traveler and he was hyper organized. And of course, he had an incredibly broad interest and understanding of much art beyond American Art. He wanted to see all the art that was out there and of course he had done his research. So, traveling with him was a real adventure. In 1974 we spent a month in France and England and in 1975 we spent a month in Spain. In 1972 my then beau Thomas and I spent a week with him in Istanbul and Izmir, where I remember a dancing bear. . . . Bill was also interested in food and restaurants . . . . The first time I came to New York City to meet with him in 1969 we had set a lunch date. New York always seemed very glamorous to me and I imagined something like lunch at the Four Seasons or The Plaza, but instead he told me to meet him at a very brightly lit orthodox Kosher restaurant in a cramped basement (not a nice Jewish deli). I had never seen anything like it . . . . I took him to lunch at the Italian restaurant near his apartment on his 90th birthday. . . . before the gala dinner [held at the Union League Club] . . . the owners treated us both since it was such a celebratory event. His death is a great blow and throws the current crisis into higher relief, changing our lives forever and leaving us much worse off than before.”

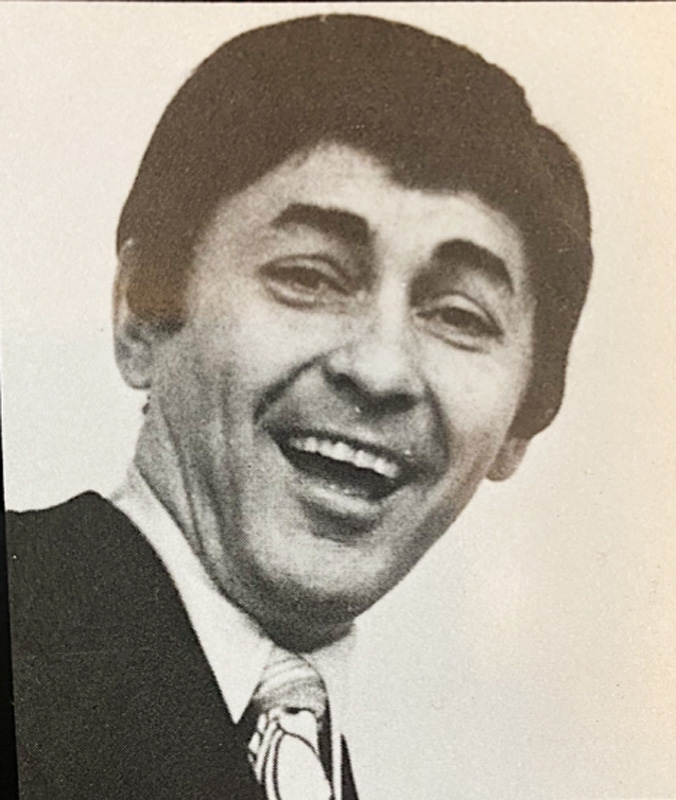

Bill (FIG. 10) was fortunate to have lived to see the field of American art blossom—thanks in no small part to his own labors—in ways unimaginable when he entered Harvard University in 1949. His curiosity and drive were insatiable, and his contributions to the study of American art were immense. We are fortunate that the career of William H. Gerdts was long, but we are even more blessed that his work will live forever.