Everyday American life changed dramatically in the first half of the twentieth century. Economic shifts, social transformations, and technological advancements all contributed to a new tenor of living marked by a rapid pace and the rise of consumer culture. Homes, workplaces, and the spaces between and beyond were newly envisioned in terms of both their design and cultural significance. American artists, many of whom continued to work in a representational style, bore witness to the inception of a modern world and interpreted it as it manifested before them. These artists variously depicted the interior as a space of reflection and rejuvenation, labor and love, transience and permanence, where the relationship between people and places reveals something deeper about subjective experience.

A current exhibition at the Columbia Museum of Art in South Carolina, Interior Lives: Modern American Spaces, 1890–1945, examines this pivotal period in history through the lenses of interior scenes and material culture. The works chosen for this exhibition place intimacy and interaction in the foreground—representational and relatable subject matter that may not immediately appear modern in nature, yet still demonstrates growing social concerns. Objects on view such as a No. 1A Gift Kodak camera designed by Walter Dorwin Teague (Fig. 3) and an armchair (Fig. 2) in the sophisticated art nouveau style from the New York manufacturer George C. Flint demonstrate the historical ascent of mass-produced consumer goods. The effects of new economic and political circumstances, as well as the tensions between new and old ways of living, are present in subtle and sometimes surprising ways.

The exhibition takes the 1890s as its starting point, a decade that encompassed the late Gilded Age and saw the beginnings of the Progressive Era. It was a time of transition; between 1870 and 1900, the US population doubled.1 Running water became the norm in urban households.2 Yet many Americans, especially recent immigrants, lived in deeply impoverished conditions, occupying tenements that would become important inspiration for the Ashcan school of painters. On the other side of the wealth gap, Gilded Age industrialists and a burgeoning middle class lived comfortably, and even extravagantly. Disposable income meant new ways to spend, and the relationship between money and social cachet accordingly took on new meaning. During this time, the economist Thorstein Veblen coined the term “conspicuous consumption,” observing that members of the leisure class cultivated personas based on the goods they acquired.

Conspicuous consumption manifested itself in myriad ways, perhaps most visibly in domestic architecture and decoration. Wealthy residences were lavishly constructed in a hodgepodge of classical European styles. Furnishings and decor were varied and eccentric, including artworks from around the globe, as well as wallpapers, antique furnishings, and other decorative arts that crafted an image of the owner’s supposed sophistication. These interior spaces were documented by painters like William Merritt Chase, who famously maintained a carefully curated studio brimming with patterns, ornaments, and an extensive collection of antiques to support his image as a debonair, urbane artiste. In Interior, Oak Manor, Pittsburgh (Fig. 4), Chase depicts the residence of Henry Kirke Porter, owner of the H. K. Porter Company locomotive manufactory. Chase’s tilted perspective emphasizes the expansiveness of the estate, which the owner had outfitted with its own art gallery. Porter only inhabited the home for a short time before his election to Congress took him to Washington, DC. During the Great War, the unoccupied estate, called Oak Manor, was offered to the Red Cross to house wounded soldiers, a token of Porter’s largesse.

Like Chase, Cecilia Beaux was among the most highly regarded painters of her time, enjoying portrait commissions from wealthy clients. The Green Cloak (Fig. 5) finds Beaux concentrating her artistic powers to acknowledge the relationship between personas and material objects. Beaux befriended the sitter, Connecticut-based lawyer and antiquarian George Dudley Seymour, in the 1880s on a ship returning from Europe; they remained friends for the rest of her life.3 Among other accomplishments, Seymour authored a book on Nathan Hale, a captain in the Continental Army of the American Revolution. In this perceptive portrait, Beaux seizes on Seymour’s interests in the revolution, painting him draped in an oversized riding cloak that reputedly dated to that period. The papers and books splayed on the desk similarly allude to the subject’s preoccupation with history. Beaux’s inclusion of two candles atop the desk further links the sitter to an earlier time, before electric lamps illuminated the home. American impressionists and society painters like Beaux and Chase had little interest in representing the seamier side of modernity. In contrast, the first decades of the twentieth century saw the steady rise of realist artists who unflinchingly tackled social problems in their art, especially in the context of urban life. While their concerns were often philosophically linked to political circumstances (many artists considered themselves communists at the time), painters like Raphael Soyer preferred to emphasize the psychological underpinnings of their subjects. Soyer sought to distinguish his work from other social realists who painted with discrete political motivations. In an oral history, he explained:

I never painted a picture of people in a factory. I never painted a picture of a policeman beating up strikers. I never painted a picture of a meeting on Union Square, something like that. . . . I never painted a very beautiful worker and a very ugly Capitalist. Now I guess those were considered Social Realism. But then I think of people in the street. I painted people who were out of work. I mean, they just sat there, either in the sun or in the shade, and did nothing. I painted them a lot. And that too may have been considered Social Realism.4

Soyer’s subject matter—everyday people, including family and friends, occupying recognizable, sometimes gritty environs—dovetailed with the socially engaged art of his peers, even as he maintained an individualized approach. While he did not, for example, explicitly document the Great Depression in New York, his work from that period inevitably reveals its effects.

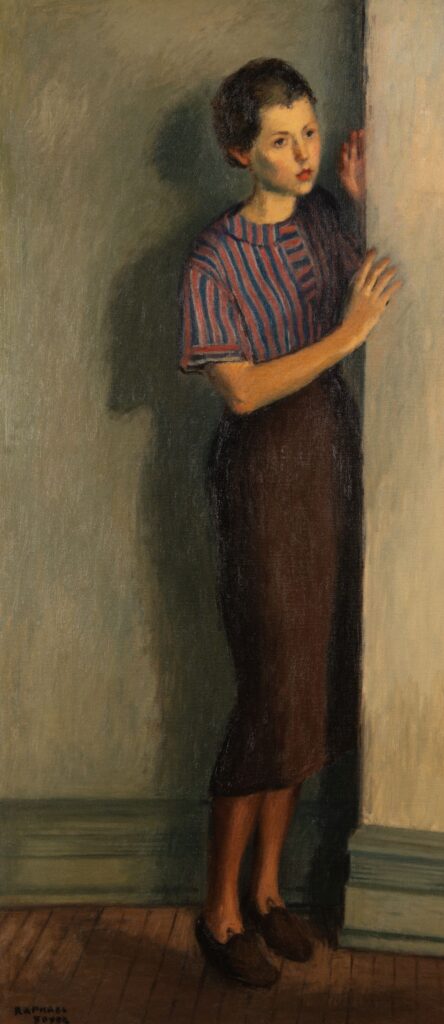

In Entering the Studio (Fig. 1), a single figure—in fact, the artist’s wife, Rebecca—hesitantly peers into a room, the architecture of which extends beyond the picture plane. Simple wooden floorboards and bare walls terminate in utilitarian molding, suggesting a modest interior. The figure’s expression is silent and quizzical. Her face, and the strip of wall on which she diffidently places her hands, are awash in a hazy, yellowish glow, presumably the artificial light of an unseen lamp. Rebecca’s simple clothes consist of an earthy brown skirt with shoes to match and a shirt with geometric stripes of red and blue (perhaps a subtle reference to the American flag). The impression is one of urban austerity, a far cry from the lavish Gilded Age interiors of the previous generation. The composition’s sparse arrangement and sense of isolation point toward the greater woes of the Depression, though the scenario is clearly particular to the artist. Speaking of the stock market crash of 1929, Soyer explained that “[it] did not affect me or anyone else I knew. We were all poor and had nothing to lose.”5 In Entering the Studio, Soyer himself is the invisible subject; the artist’s commitment to his vocation amidst financial hardship imparts a silent tension that rhymes with the times.

Walter Ufer’s The Listeners (Fig. 7) offers another intimate interior with cultural implications extending far beyond the canvas. Ufer, a member of the Taos Society of Artists, was a politically engaged painter who famously documented Native American life in New Mexico. In The Listeners, Ufer paints Jim Mirabel, a Taos Pueblo man the artist befriended, amidst a carefully arranged studio. The adobe home is filled with cultural objects drawn from local Indigenous populations: pottery, a Navajo rug, a partially visible animal hide. A pianist (likely Ufer’s wife) plays music for an audience of three, including Mirabel, whose right arm rests coolly atop the piano. No two figures make eye contact, though Mirabel stares directly at the musician. The pianist’s solemn expression hints that she is conflicted about her role, and the sense of disquiet seems linked to a clash of cultures. The work’s subject and title indicate a paternalistic exchange between Anglo-American and Native populations, where the latter are inevitably instructed to “listen”—here a euphemism for compulsory cultural assimilation.6 Two years before The Listeners was painted, President Calvin Coolidge signed the Indian Citizenship Act into law, for the first time granting citizenship to Native Americans. The work might reflect Ufer’s concerns about the new law’s ramifications, encouraging a deeper reflection on the complexities of Indigenous and Anglo-American relations.

As Ufer sought to rectify new sociopolitical realities in the Southwest, the portrait painter Edwin Harleston responded to cultural shifts in the South. Born in Charleston, South Carolina, to a prominent African American family, Harleston studied briefly at Harvard University before transferring to the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He returned to Charleston in the early 1910s and was struck by the changes that had befallen the city in his absence. Economic distress and increasing racial tensions marred the decade, culminating in a violent riot in 1919. Harleston’s natural response was to involve himself in activist causes; in 1917 he became the first president of the NAACP’s Charleston chapter. In 1922 Harleston and his wife, the photographer Elise Forrest, opened a portrait studio for the benefit of African American community members. It was there that Harleston painted Miss Bailey with the African Shawl (Fig. 6).

The subject of this striking portrait is Sue Bailey, then a traveling secretary for the YWCA.7 Bailey passed through Charleston on assignment in 1930 and stayed with the Harlestons, offering occasion for both Edwin and Elise to render her visage in their respective mediums. Harleston depicts Bailey with a direct gaze and air of mature confidence, although she was only in her twenties at the time. The “African shawl” elegantly worn by the sitter (which may or may not have actual African provenance) could hint at her professional position, which necessitated international travel. The garment might also constitute a painterly nod to the burgeoning New Negro aesthetic movement, whose proponents looked to African sources for inspiration. The same year that Harleston met Bailey, he executed a portrait of the artist Aaron Douglas, whose own work was stimulated by African art. Harleston’s preferred method was decidedly classical in comparison to his modernist colleagues’, yet he shared their sentiments in amplifying and developing uniquely African American content.8

The works discussed here merely offer a glimpse into a multivalent subject. While the exhibition does not present a comprehensive view of a time or a nation, the selections reveal something about how people live, adapt, and triumph in the face of trying circumstances. Though diverse in their regional and social settings, these artists and others represented in Interior Lives are united as Americans who actively navigated the unchartered historical transition into modernity. They synthesized their world in realist terms with a personal bent, creating a unique index of experience. They explored change through the familiar and simultaneously traversed the liminal space between material and mind.

This article is adapted from an essay originally published by the Columbia Museum of Art in South Carolina in conjunction with the exhibition Interior Lives: Modern American Spaces, 1890–1945, which is on view until May 24.

1 Charles W. Calhoun, “Introduction,” The Gilded Age: Essays on the Origins of Modern America, ed. Charles W. Calhoun (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1996), p. xi. 2 Robert G. Barrows, “Urbanizing America,” ibid., p. 104. 3 On Beaux’s relationship with Seymour, see Alice A. Carter, Cecilia Beaux: A Modern Painter in the Gilded Age (New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 2005), p. 105. 4 Milton Brown for the Archives of American Art, “Oral history interview with Raphael Soyer, May 13–June 1, 1981,” available at aaa.si.edu, accessed on December 12, 2023. 5 Raphael Soyer, “An Artist’s Experiences in the 1930s,” in Patricia Hills, Social Concern and Urban Realism: American Paintings of the 1930s (New York: American Federation of Arts, 1983), p. 27. 6 I consulted the Philbrook Museum of Art’s object file, which included an excerpt from Enchanted Visions: The Taos Society of Artists and Ancient Culture, ed. Jochen Wierich (Spokane: Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, 2005). Of further interest is John Ott, “Reform in Redface: The Taos Society of Artists Plays Indian,” American Art, vol. 23, no. 2 (Summer 2009), pp. 80–107, which discusses the complicated relationship between the Taos Society of Artists and the Pueblo populations of New Mexico, with special attention paid to Ufer. 7 Bailey, who married the theologian Howard Thurman in 1932, went on to a long career as a prominent Civil Rights advocate in the ensuing decades. 8 Important biographical data for Harleston and the inferred connection between the African shawl and the New Negro movement are found in the second chapter of Laura Augusta Lindenberger Wellen, “Looking Forward Together: Three Studies of Artistic Practice in the South, 1920–1940” (PhD diss., University of Texas at Austin, 2012).

MICHAEL NEUMEISTER is the senior curator at the Columbia Museum of Art.