The George Read II House, perhaps the best example of a Philadelphia Federal-style house still in existence, has stood on the banks of the Delaware River in New Castle for more than two hundred years. Built between 1797 and 1804 by the son of a signer of the Declaration of Independence and United States Constitution, the twenty-two room National Historic Landmark today is maintained by the Delaware Historical Society. Last year, the Read House welcomed a new director, Brenton Grom. We caught up with Grom and asked him about his path to becoming director of a house museum—in a time when house museums are having to reinvent themselves to stay relevant—and about what he’s been doing to attract new visitors.

Sammy Dalati, The Magazine ANTIQUES: First of all, can I ask what your personal entry point to the decorative arts world was?

Brenton Grom: My background is not conventional. I did my undergrad at the Oberlin Conservatory of Music where I studied piano and music history. It was in the course of doing graduate work in musicology (working on vernacular psalm and hymn-singing traditions in New England in the early nineteenth century) that I found myself becoming more a social historian than somebody who was focused on the music itself. So I changed disciplines and came to study early American history and material culture at the University of Delaware.

SD: How did you get involved at the George Read II House?

BG: I had been working for a couple of years as the curator of special collections for the Delaware Historical Society. It was an exciting time for people in the field to regroup and think about what would come next, and when the director of the Read House left for another position it seemed like a really interesting opportunity to take on a fantastic house that was not getting as many visitors or as much attention as it really deserved. The Read House had been lived in by private owners until 1975, and starting in 1976 there was a complete restoration campaign—interior and exterior—to roll back many of the rooms to how they might have been during the period when the Read family owned it, which was pre-1846.

I have to say: It’s easy to look back at these early efforts and say “well, folks just weren’t going about this the right way but we’re going to actually do something now,” but the Read House as it exists today is the result of a generation doing what seemed most appropriate at the time, making use of exceptional scholarship and workmanship. We continue to benefit from that.

SD: But you are making some changes to the house’s program? What sort of changes?

BG: Some historic properties have done amazing things by just flipping the narrative about, for example, enslavement, servants’ lives, or immigration—social questions that traditionally were tucked away behind all the pretty rooms. At a place like Whitney Plantation in Louisiana, that sort of reevaluation of historic house’s history has led to very striking results. But what I came to realize at the Read House was that we couldn’t just flip the script and expect everything to change. My predecessors had introduced information about household labor into the tour experience, but that wasn’t really doing anything to change our numbers.

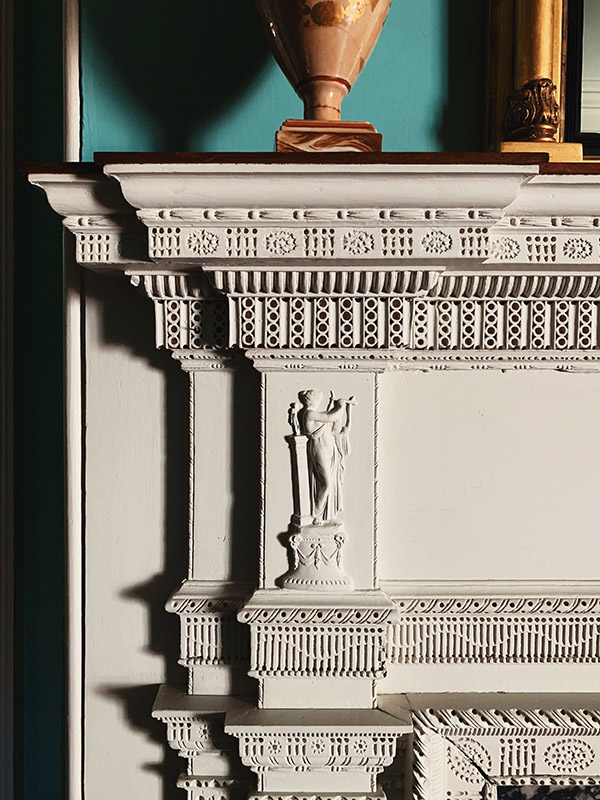

We recognized that above all else the Read House is a spectacular piece of architecture. There are architectural details on the interior that are peculiar to the Philadelphia region, an example being what we call punch-and-gouge woodwork, a carving you see on almost all the doors and windows. It’s basically a motif of grooves and holes made with a gouge and a drill, and it’s something that really exploded in popularity around the turn of the nineteenth century. The Read House has more of it than any house in America.

And it’s not just about the architecture and ornamentation, but the way that light comes into these spaces—the way that these spaces feel is really gratifying. With digital platforms like Instagram exerting a powerful influence on visual culture, we’re now in this new golden era of popular interest in design. Young people want to curate their lives with meaningful objects, so our objective is to give people any opportunity to come and enjoy the beauty of the Read House without being herded through on a tour. If they think something is just gorgeous and they want to Instagram it and they don’t know why—beyond the fact that it relates to their own sensibilities in some way—well, let’s let them start with that.

To help enable this freer interaction with the house we’re considering adding wall labels that will supply the kind of information that tour guides normally would be doling out, so people can educate themselves (if they wish) while interacting with the space as they see fit. We’re also very interested in working with contemporary designers to shake up these spaces and create a dialogue between the historic architecture and some of the historic collection pieces. This might include adding contemporary lighting fixtures, juxtaposing modern and period furniture pieces, adding modern wallpapers and modern carpets, etc.

And though we’ll be moving away from the sort of staged tableaus normally found in house museums, we intend to honor the vision of late twentieth century scholars by making available tablets or other reality-augmenting technologies that will allow visitors to see how the period stagings in the house used to look.

SD: It sounds like a lot of work! Any advice you could offer to others with historic properties or historic objects in their care who want to make sure the world’s seeing them?

BG: I would say that for a lot of Gen-Xers and Millennials, and now Generation Z, they don’t see why they should care about historic houses. And I think instead of writing them off as wrongheaded we owe them thoughtful answers. I believe we have to start by looking at the world that we live in and asking how these cultural assets in our charge can participate in that world instead of being locked away in the past.