This article was originally published in the January 2006 issue of ANTIQUES.

Like most nineteenth- and early twentieth-century jewelry manufacturers in Newark, New Jersey, Henry Blank and Company until recently had been long forgotten. However, it was one of the largest and most successful Newark firms from the 1890s until well after World War II. The finest jewelry retailers sold first its jewelry and subsequently its watches. Beginning about 1910 the company’s specialty was women’s jeweled wristwatches, examples of which are most often seen on the market today. The company also made women’s pendant, chatelaine, and purse style watches as well as men’s wrist- and pocket watches.1

The company’s watches were sold all over the United States by jewelers large and small. Tiffany and Company was Blank’s largest account.2 Henry Blank (Fig. 1), and later his son Harry (b. 1896), visited Tiffany’s offices every week beginning about 1911.3 Other New York City customers included Marcus and Company, Black, Starr and Frost, Raymond C. Yard, Udall and Ballou, and Brand-Chatillon. J. E. Caldwell and Company, and Bailey, Banks and Biddle of Philadelphia; Shreve, Crump and Low of Boston; and Grogan Company of Pittsburgh also regularly bought Blank watches between about 1910 and 1930. Spaulding and Company of Chicago and Shreve and Company of San Francisco were customers, and there is also evidence that Blank made watches for Patek, Philippe and Company in the 1920s, and later for Cartier.4

Large jewelers would generally have their name imprinted on the watch dial, but dozens of smaller jewelers around the country bought watches without their name through the company’s traveling salesmen. By 1910 the company had hired four traveling salesmen to cover the United States, and it maintained regional sales representatives for many years.

Henry Blank and Company was founded in 1890 in Newark as N. E. Whiteside and Company by Newton E. Whiteside (1843–1922), an experienced jewelry salesman.6 Like many other Newark jewelers, it manufactured fourteen-karat gold brooches, bracelets, cufflinks, vest buttons, studs, scarf pins, and watch fobs as well as sterling silver novelty items. In 1899 Henry Blank bought one third of the company for six thousand dollars and became the junior partner. The name was changed to Whiteside and Blank, with Blank in charge of production.

Henry Blank was born to German parents in Providence, Rhode Island, and spent his youth in Philadelphia, to which the family moved. After leaving school in the eighth grade, he worked his way up from porter’s assistant in the jewelry shop of Durand and Company, one of the most prominent jewelers in Newark, to an apprentice. He had become a goldsmith in the jewelry department by the time he was twenty-one, but thinking his prospects might be better in business, he worked as a manager for the Prudential Life Insurance Company in Jamestown, New York, until buying into the Whiteside company.7 After Newton Whiteside retired in 1912, Blank bought out his shares over a period of five years and renamed the company Henry Blank and Company in 1917.8 He remained president until his death, and his four sons then managed the company until it closed in 1986.9

Beginning in 1907, Henry Blank traveled to Europe each spring to purchase stones and other supplies and seek the latest European fashions. He quickly expanded the firm’s line, adding platinum, diamond, and plique-a-jour jewelry, festoon necklaces, sautoirs, lavalieres, and lockets.10 While most were made in the prevalent garland style, there were also art nouveau, filigree, novelty, and Egyptian style objects. Always, quality was a major priority.

On one of his early trips to Pforzheim, Germany, Blank bought the American rights to an expansion bracelet for wristwatches that had been invented by a German. After his first customer reneged on its order for bracelets, Blank brought back Swiss watch movements from his next European trip and combined them with the bracelets to produce the company’s first watches in 1911.11 The lathe-turned cases were round and contained various brands of movements. Almost immediately Blank introduced watches with bezels ornamented with guilloche enamel, platinum, and diamonds. Wholesale prices ranged from about forty to more than five hundred dollars.

Blank’s introduction of strap-band watches coincided with the time that women in the United States were becoming aware of them. European jewelers were ahead in wristwatch production. In Paris, Cartier had introduced watches with strap bands in 1906. Within a few years the firm was making not only a wide range of case shapes and jeweled bezels, but also straps of leather, black silk ribbon, pearl mesh, and diamonds.

According to its so-called Blue Books, in 1903 Tiffany and Company introduced wide leather straps into which a pocket watch could be inserted for wrist wear. In 1909, when Cartier opened its first store in New York City, Tiffany listed gold watch bracelets with leather straps, gold links, and fancy links for $70 to $250. If the links were set with diamonds, the prices could rise to $1,300. In 1912 Tiffany offered platinum watch bracelets with links that could be set with diamonds.12

By 1914 Blank was producing pearl-mesh and black ribbon straps in imitation of Cartier, along with oval, barrel, square, and hexagonal bezels (see Pl. VI). These types of watches proved popular, and by 1919 most watches that appear in Blank’s pattern books were made with the black ribbon strap. The company produced its first man’s wristwatch in 1914 and about the same time began to make pocket watches.

Blank’s strategy of bringing European design to American jewelry stores was successful. Sales exceeded $1.4 million in 1919 during the post-World War I rush to buy, and they remained high throughout the 1920s. During that decade the firm made more than fifteen hundred styles of women’s wristwatches, as well as some two hundred styles of sautoir and ring watches, and, beginning in 1929, more than one hundred styles of folding purse watches. Styles ranged from plain gold bezels for less than $100 wholesale to completely jeweled platinum bracelets that sold for several thousand dollars. The average price of the firm’s women’s wristwatches was more than $300 wholesale.13

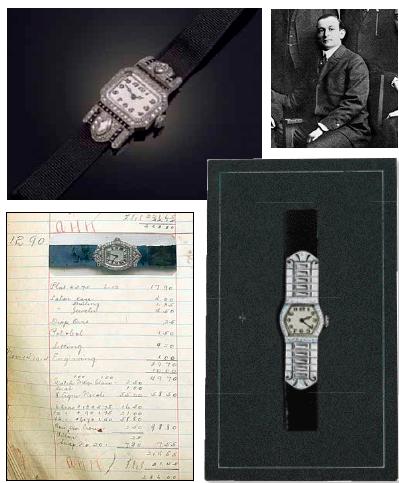

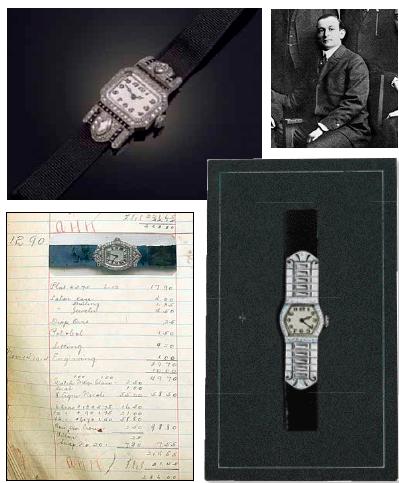

During the 1920s women’s ribbon strap watches dominated production. The majority of the watches themselves were ornamented with diamonds and platinum in a geometric, generalized art deco style, sometimes including black onyx or colored stones (see Pl. IV). Often the diamond bezel would be hinged at each end so that it appeared to continue around the wrist. The company would also customize watches to suit its customers’ tastes and price ranges. A drawing in the Blank papers (Pl. V) depicts a watch that could be made in more or less elaborate versions.14

Pl. IV. Wristwatch made by Blank and Company,1920-1925. Platinum, diamonds, and onyx. Photograph by courtesy of Skinner, Bolton, Massachusetts.Fig. 1. Henry Blank (1872-1949) of Whiteside and Blank, detail from a photograph of the company’s shareholders, 1907. 7 9/16 by 9 1/2 inches overall. Blank and Company papers; Helga photograph.Pl. V. Design drawing for a wristwatch by Blank

and Company. Pen and ink and gouache on paperboard; sheet size 5 3/16 by 3 1/8 inches. Watch length 3 7/16 inches. Blank and Company papers; Helga photograph.

During this decade of exuberant consumerism, Blank followed the example of Cartier and other European jewelers and made ever more elaborate types of watch straps. Mesh bracelets of seed pearls and wire were constructed by hand in Blank’s factory. Such bracelets were often paired with a geometric bezel set with diamonds and precious stones. The example in Plate VII, made for Tiffany, had a wholesale price of $1,460 in 1923. An alternative strap was platinum mesh, which could also be used in place of ribbon for almost any bezel design.15 Occasionally the mesh was edged in diamonds for a spectacular effect.

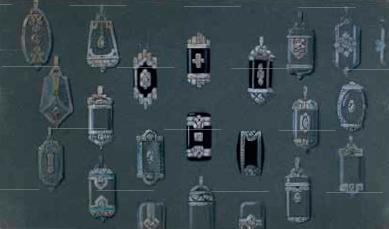

Pendant watches were among the most popular alternatives to wristwatches for women in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Blank made at least one series of black enameled rectangular pendants ornamented with diamonds (see Pl. XI). An example from this group, with a fleur-de-lis inside a hanging basket of diamonds (Pl. IX), is shown in the pattern book suspended from a black cord at a wholesale price of $405 in 1924. Chatelaine watches were also fashionable. They swiveled so they could be read while suspended from a brooch. The example shown in Plates Xa and Xb, made for Tiffany, demonstrates the transition between the garland and art deco styles. The platinum, diamond, and black-enamel watch is decorated on the reverse with a traditional floral design within a wreath. It is suspended from a geometric platinum-mesh brooch set with diamonds and squarecut onyx.

Pl. IX. Pendant watch with later gold pendant brooch

made by Blank and Company, c. 1921. Diamonds,

enamel, and gold. Christie’s Images photograph.

To satisfy the growing demand for novelty watches, Blank experimented constantly. A lorgnette watch originally made in 1917 is one of the most unusual innovations (Pl. XII). The diamond handle conceals the watch face on the reverse. Ring watches were another form the company manufactured, although in a much smaller variety of styles.16 A particularly successful novelty watch was the sliding purse watch developed by Cartier, Movado, and other European jewelers in the late 1920s. Blank’s colorful versions (see Pl. I) are clearly adapted from the stylish geometric patterns and Asian inspired motifs of the European examples. Blank applied for at least two patents for the spring mechanism that raised the watch out of its case. The example illustrated in Plate XIII was made in several different colors.

Although the company’s specialty was women’s watches, it also produced large numbers of more simply styled men’s wrist- and pocket watches.17 Men’s watches were made in greater quantities after World War I, when a wristwatch became an acceptable accessory.

Pl. XI. Design drawing for pendant watches, 1915-1920. Graphite, ink, and gouache on paperboard; 6 1/2 by 11 inches. Blank and Company papers; Helga photograph.

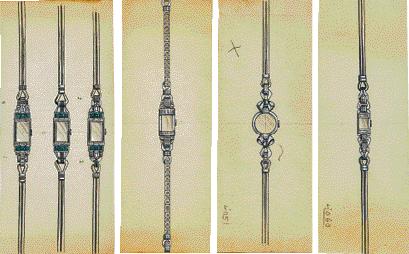

During the late 1920s, as jewelry grew larger and bracelets wider, a new lady’s wristwatch style appeared from Europe. Inexpensive and delicate, it consisted of a woven silk cord looped through the bezel to form the strap. Cartier was producing these diamond cord watches by 1926, and Henry Blank may have been the first American manufacturer to import silk watch cords from Europe, since the company’s first versions also appeared in 1926. The cord watch dominated the company’s production through the 1930s, growing more delicate and curvilinear over time (see Pl. XIV). Its popularity may be traced, as the company’s drawings demonstrate, to the emerging need for less expensive watches.

Like many other firms, Blank suffered during the Great Depression. Employee records indicate that all but a handful of workers were laid off between 1931 and 1936, and far fewer styles of watches were produced, matching a sharp decrease in orders.18 However, Blank did produce some fairly substantial wristwatches in the 1930s that demonstrate the curves, color, and dimensionality then being introduced to jewelry. Watches from the end of the 1930s and into the 1940s reflect the “cocktail” style, characterized by larger colored stones and a snake chain or gold links for a strap. Often these had a bold, asymmetrical look.

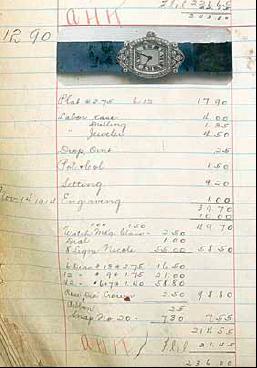

Pl. VI. Costs for platinum and diamond watch no.1290 by Whiteside and Blank, dated November 14, 1914, in oversized pattern book 8. The wholesale price of the watch was 5. Blank and Company papers; Helga photograph.

The simplest way to identify a Blank and Company watch is by the trademark, which was usually stamped inside the watchcase or on the reverse of a piece of jewelry. The symbol had been established by N. E. Whiteside and Company and was used throughout the life of the Blank company. The mark is sometimes identified as that of the Cresarrow Watch Company, which Blank established as a subsidiary in 1924. It made a line of less expensive watches of white gold, which became a popular and economical alternative to platinum. The venture was originally called Davis and Lowe for two longtime Blank employees, and at least some watches in the line are stamped “D&L.” Sometime in the 1930s the company was renamed the Cresarrow Watch Company, and by 1960 the Cresarrow line was the only one Blank produced.19

Another way to identify Blank watches is by the movements used. By 1916 Henry Blank had hired an agent and set up an office in Geneva to import the thousands of watch movements and precious stones the firm needed. In 1912 he bought the American rights to movements produced by the International Watch Company in Schaffhausen, Switzerland, which the company kept exclusively until about 1950. These movements were most often used in men’s wrist- and pocket watches. The C. H. Meylan Watch Company of Le Brassus, Switzerland, also supplied Blank with movements through an exclusive agreement for the United States market. The Meylan ébauche was particularly well suited for women’s watches because it was small, thin, and was produced in many shapes. Blank bought the majority of the company’s limited output into the 1930s.20 These Swiss movements were of the highest quality and quite expensive, ranging from fifty to one hundred dollars, with the smallest ones approaching two hundred dollars. During the 1920s, Henry Blank also began ordering movements made to company specifications. They were engraved “Cresarrow,” based on the company trademark, or “E. Huguenin,” for the company’s Geneva agent. They were slightly less expensive, and the majority was used for the Davis and Lowe line.21 Pattern books indicate that, especially during the early years of watch production from about 1910 into the early 1920s, Blank bought other movements, but apparently not a great quantity of any one brand.22

The staff at the Blank manufacturing facility in Newark ranged from a few dozen people to eighty or ninety in the peak years of the 1920s.23 The head designer from 1912 to 1935 was Frederick Bieberbach (b. 1877), a first generation German who worked closely with Henry Blank and would sometimes accompany him to Europe. Bieberbach and his staff created groups of drawings with various motifs based on Blank’s suggestions or ideas gleaned from European samples. After the drawings were approved many skilled workers were needed to bring them to life. Steel engravers, toolmakers, press hands, turners, engravers, enamelers, diamond setters, polishers, and chain and mesh makers were all employed at the factory. Watch construction also required dial makers, glass cutters, and watchmakers. Hundreds of craftsmen worked at the factory over the decades, including men, women, Americans, Germans, Italians, and other nationalities. Many workers stayed for years and came back after being laid off during the 1930s. The factory also took on many apprentices—dozens in the 1920s, although that number dropped sharply during and after the Depression.

Henry Blank and Company was a long-lived and successful jewelry manufacturer because it created a place for itself with its top quality, high-end jeweled watches. It was able to make a wide variety of styles and to adapt them to emerging fashions, during both good times and bad.

1 Much of the information about Henry Blank and Company in this article has been drawn from the archives of the New Jersey Historical Society, Newark, Manuscript Group 1273. The firm’s last president, Peter Blank, a grandson of the founder Henry Blank, donated the records after he closed the company in 1986. The archive consists of twenty-five boxes of ledgers, photographs, dies, records, and thousands of drawings. There are also thirty-three oversized pattern books and ledgers, board of directors’ meeting minutes, account books, and stock certificates. Although some financial information, the earliest pattern books, and drawings from various periods are missing, the archive comprises a fairly comprehensive history of the company. For more information about the enormous contribution of the Newark jewelry industry, see Ulysses Grant Dietz et al., The Glitter and the Gold: Fashioning America’s Jewelry

(Newark Museum, Newark, New Jersey, 1997). 2 The name appears most frequently on watch dials in the pattern books over the years, and Peter Blank also confirms this. Watches with the Tiffany and Company name on the dial also appear most frequently on extant Blank and Company watches. 3 Ralph E. Blank, “History of Henry Blank and Company,” 1988, pp. 5, and 22, private collection. This unpublished manuscript by one of Henry Blank’s sons has also helped with information on the company. 4 All of these names and many more were found on the faces of watches in the pattern books in the company papers. 5 Blank, “History of Henry Blank and Company,” pp. 5 and 6. Payments to traveling salesmen are recorded in entries for 1915 and 1927 in oversized ledgers, Henry Blank and Company papers. 6 Newton Whiteside had been a jewelry salesman for A. J. Hedges and Company for more than twenty years. In 1890 he was in partnership with John W. Fahr. When this was dissolved in 1895, he continued in business alone. The business was first located at 54 Columbia Street in Newark, but by 1895 it had moved to 93-95 Green Street, and in 1900 it moved to 17 Liberty Street, where it remained for more than eighty years. See Dietz et al., The Glitter and the Gold, p. 163. 7 Blank, “History of Henry Blank and Company,” pp. 2 and 3. Peter Blank also confirmed these facts. 8 Corporation agreements and buyout agreement in box 3, Henry Blank and Company papers. 9 Henry M. Blank, known as Harry, began working for the company in 1920 and eventually led the New York sales office at Fifth Avenue and Forty-fourth Street in the Guaranty Trust Company vaults. He took over as president after his father’s death until the early 1950s. Philip E. Blank (1898-1985), who came to the firm in 1916, was sent to Europe to learn about gemstones and the manufacture of watch parts. He became president of the company in 1954 after his brother Harry’s retirement. Carl P. Blank (1902-1969), joined the company in 1927 and managed the watch workshop. Ralph E. Blank (1905-1990), who came to the business in 1930, was involved in sales around the country. He became president in 1971. Philip’s son, Peter Blank joined the company in 1956, worked in sales with Ralph, and was president from 1980 until he closed the firm in 1986. Henry Blank and his wife, Phoebe, also had a daughter, Hortense, who will celebrate her ninety-seventh birthday in February 2006. The family lived on Ridgewood Avenue in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, in a 1907 Georgian-style brick house, which still stands. Its interior, designed by Henry Blank himself, is largely intact. 10 For an example of Blank’s plique-a-jour work, see Janet Zapata, “American plique-à-jour enameling,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 150, no. 6 (December 1996), p. 819, Pl. XV. 11 Box 21, Henry Blank and Company papers, contains sections of the first bracelet. Blank, “History of Henry Blank and Company,” p. 6, notes that the first bracelet order came from A. Wittnauer and Company, the importer of watches by Longines of Switzerland (founded 1832). 12 See Tiffany and Company, Blue Books, 1903-1912. 13 Production Ledger of Stock Items, 1904-1952, box 6, Henry Blank and Company papers, indicates pattern numbers and quantities produced. Average prices were calculated by dividing yearly sales by the number of items produced. During the 1920s, the average ranged from about $300 to $600 wholesale. The markup for retail at this time was generally less than keystone (double the wholesale price). 14 For an example of a watch made for Tiffany and Company based on this drawing but with a shorter bezel, see Sotheby’s, Hong Kong, Important Jewels and Watches, May 1, 1997, Lot 1471. 15 For an almost identical example to the one shown in Pl. V, except with a platinum mesh strap, see Sotheby’s, New York, Magnificent Jewels, October 16, 2002, Lot 95. 16 For an example of a Blank ring watch, see Skinner, Boston, Fine Jewelry, September 14, 1999, Lot 394. 17 For an example of a man’s watch made for Tiffany and Company in the 1920s, see Christie’s, New York, Important Pocket Watches and Wristwatches, June 5, 2003, Lot 152. 18 Records in box 7 and Production Ledger of Stock Items, 1904-1952, Henry Blank and Company papers. 19 The company also used the brand name Cresaux in later years-generally printed on watch dials. Today Blank watches frequently come up for sale at auction houses and on the World Wide Web. If identified at all, they are generally said to be made by the Cresarrow or Cresaux Watch Company. I have identified at least one watch in the marketplace marked “D&L.” 20 Blank, “History of Henry Blank and Company,” pp. 7, 8, 19, 20, 33, 34, 36, and 37, discusses the company’s various suppliers of watch movements. Peter Blank has also confirmed this information. 21 The Geneva office operated from at least 1916 into the 1950s according to ledgers in Henry Blank and Company papers, box 5, and oversized book journals 1937. Blank, “History of Henry Blank and Company,” p. 7, discusses the setup of the Geneva office. 22 Oversized pattern books 7 and 8, Henry Blank and Company papers. Some other names of movements that were used include Bonny, Nicole, Gigon, Bailly, and Jacoby. Most of these appear to have been less expensive than the Meylan movements. 23 Employment cards for almost everyone who worked at the factory are in box 7, Henry Blank and Company papers. See also Blank, “History of Henry Blank and Company, pp. 20-21.

LESLIE SYKES-O’NEILL is an antique jewelry and silver specialist at S. J. Shrubsole in New York City.