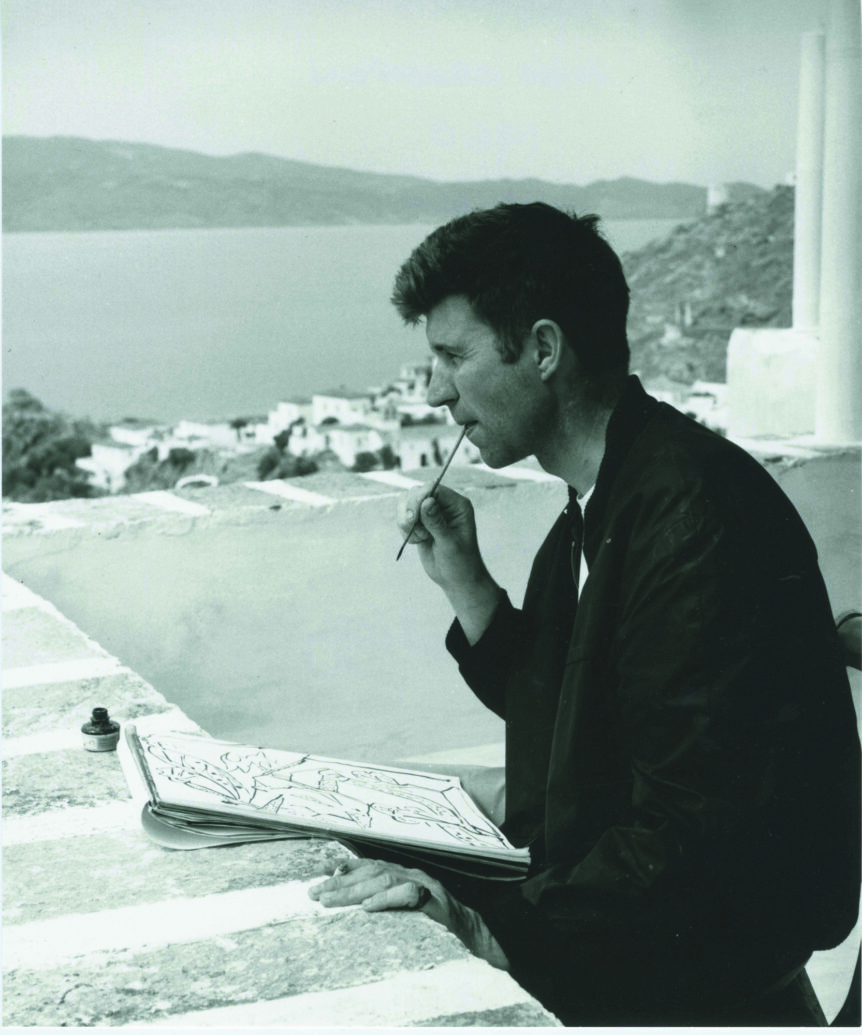

John Craxton (1922– 2009) drawing at the house of painter Nikos Ghika (1906–1994) on the island of Hydra, Greece, in a photograph by Wolfgang Suschitzky (1912–2016), 1960. Photograph © Wolfgang Suschitzky, courtesy of the Benaki Museum of Greek Culture and the Ghika Gallery, Athens, Greece.

A painter, designer, draftsman, and longtime resident of Greece, John Craxton was one of those eccentric British modernists, like his friends and near contemporaries Paul Nash, Graham Sutherland, John Piper, Ivon Hitchens, and Keith Vaughan, who achieved a significant measure of recognition or renown at various points in their careers in the mid-twentieth century, but are woefully underknown or under-appreciated in today’s art world. Francis Bacon and other School of London practitioners have certainly overshadowed their achievements in the annals of recent British art.

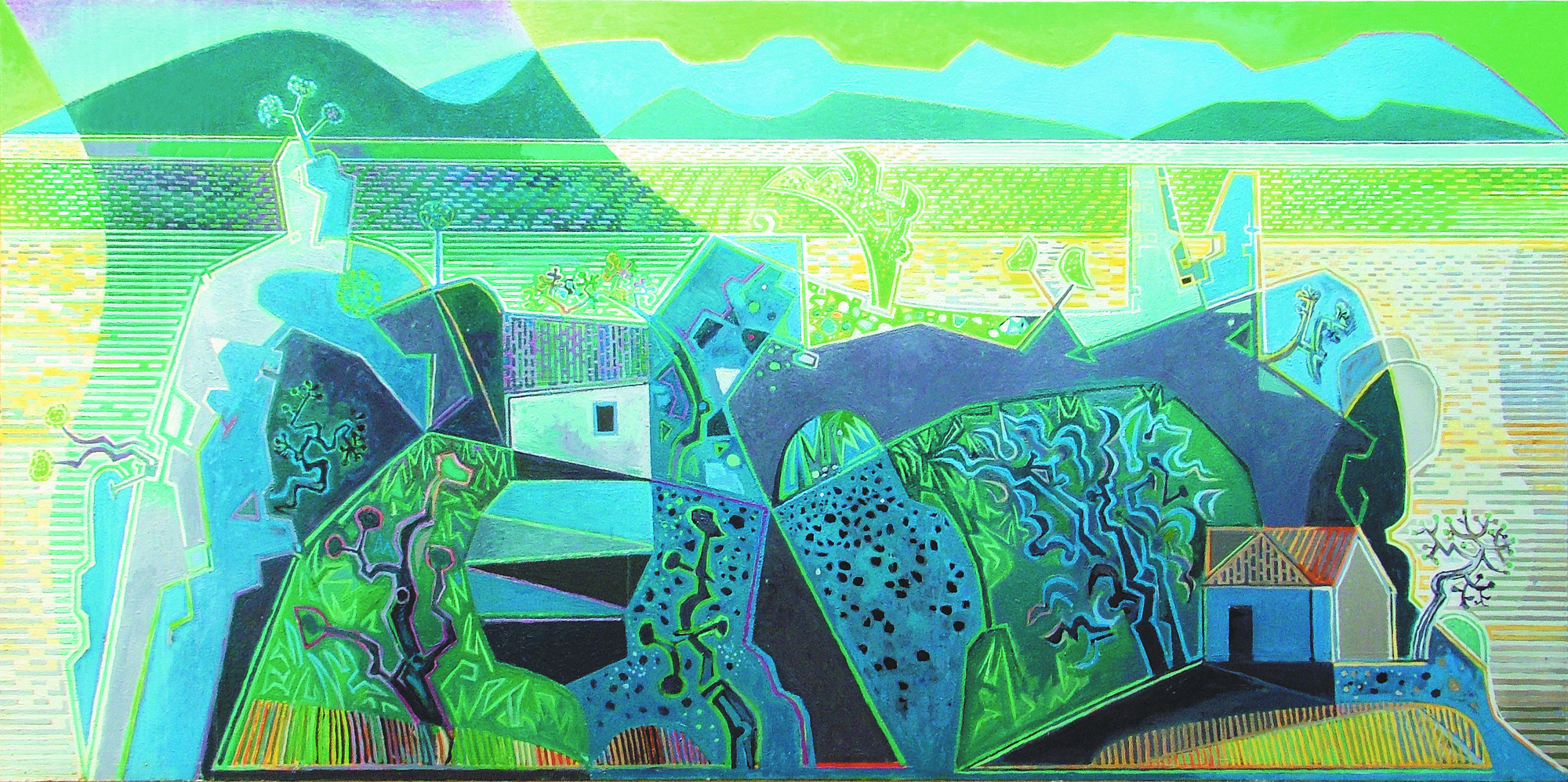

Landscape with the Elements by Craxton, 1975–1976. University of Stirling, United Kingdom. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in the collection of the Craxton Estate, London; photographs © Craxton Estate, courtesy of DACS (Design and Artists Copyright Society), London.

Occasionally, however, an exhibition comes along that offers a more equitable treatment of an artist and a rare opportunity to reassess their work. Such is the case with John Craxton: A Greek Soul, a gem of a survey that debuted at the Benaki Museum of Greek Culture in Athens—where I saw the show—and is currently on view at the Municipal Art Gallery of Chania on the island of Crete. In the spring, the exhibition will travel to Istanbul, and plans are in the works to bring the show to London later this year.

Organized by Craxton’s friend and biographer Ian Collins, the exhibition contains some ninety works, including numerous paintings and works on paper never before shown publicly. Also on view are photos and other archival materials, plus several examples of classical Greek art—ancient sculpture (including a marble bust that Craxton once owned and eventually donated to the Benaki)—and Byzantine paintings like those that inspired him. One of the most outstanding works on view, Landscape with the Elements (1975–1976), a sumptuous, mural-size tapestry (approximately 13 by 17 feet), is displayed on an upright, slightly beveled platform in a darkened room (due to the fragility of its threads in five hundred colors). Redolent of Craxton’s painting style of the period, and made using traditional Greek weaving techniques, the tapestry shows a highly stylized landscape based on an imaginary Grecian harbor scene. A blazing sun high in the sky on the right shines on a shimmering sea, while on the left a brilliant crescent moon illuminates a shadowy nocturnal landscape. Craxton designed the piece, commissioned by the University of Stirling, and oversaw its production by Dovecot Weavers in Edinburgh, Scotland. He worked there during the nearly ten-year period he was exiled from Greece in the wake of the military coup of 1967, the “time of the colonels,” as the repressive junta came to be known.

Alderholt Mill by Craxton, 1943–1944.

Born in London to parents who were musicians and music educators, Craxton was the most rebellious of their six children, and he was gay. A free spirit and a terrible student, he was routinely expelled from schools. But he began to draw at an early age, and revealed a special talent for portraiture. When sympathetic relatives took him to the Pitt-Rivers Museum in Dorset, he began to cultivate an obsession with all things Greek and longed to go there. He became enamored with works of ancient Greek art he saw in the museum: Cycladic sculptures, Minoan pots, and Fayum portraits. Byzantine paintings and mosaics particularly captivated him. Eventually, he discovered the paintings of El Greco, who remained a favorite throughout his life. All of these early influences can be observed in his work throughout his career.

Excused from military duty for health reasons, he lived during the war years in London, where he shared with like-minded artist Lucian Freud a studio paid for by arts patron and Horizon magazine co-founder Peter Watson. In 1943 the trio visited Graham Sutherland, the pre-eminent English painter of the day, on the rugged west coast of Wales, which proved to be a pivotal event for Craxton.

Two Figures and Setting Sun by Craxton, 1952– 1967.

“Graham helped Craxton—who was nineteen years younger—to extract elements from a landscape and to invent it afresh,” Roger Berthoud noted in Graham Sutherland: A Biography. “They went drawing together in Wales and Graham demonstrated how he took a detail of landscape and enlarged it . . . . With youthful pretentiousness, [Craxton] once asked Graham: ‘Would you say paintings are made of two facets, flesh and bones?’ ‘No, flesh and spirit,’ Graham replied.”

Landscape, Hydra by Craxton, 1963–1967.

Sutherland and Craxton shared a passion for works by the nineteenth-century British romantic painter Samuel Palmer (1805–1881), whose art encompassed a spiritual quest; and their works were often labeled neo-romantic, a label both artists disavowed. Nevertheless, Craxton’s earliest pieces in the show, such as Poet in Landscape (1941), and Alderholt Mill (1943–1944), with its expressively exaggerated trees and undulating clouds filling moody skies, have a neo-romantic bent and reflect the influence of both Palmer and Sutherland.

After the war, Craxton finally had the opportunity to travel to Greece. Compared with Britain’s drab postwar environs and dismal climate, the young artist found the warmth and brilliant Mediterranean light exhilarating. And he was also attracted to the ruggedness of the landscape, as well as to the sailors and fisherman who populated the Greek port towns. He never wanted to return to England. He settled initially on the islands of Poros, and then Hydra, relatively close to Athens, which was a gathering place for postwar ex-pat intellectuals and well-known artists and writers, as it still is to some extent today. He befriended the future Nobel Prize–winning poet George Seferis, travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor, and Greek painter Nikos Ghika, with whom he roomed for extended periods of time. In his own work, however, Craxton was compelled to draw and paint the local residents— especially the men who frequented the tavernas—plus the surrounding land-and seascapes, as well as the goats and cats that thrived on the islands.

Craxton held a number of successful gallery exhibitions of these works at the British Council in Athens, as well as in England. In 1951 he was invited by choreographer Frederick Ashton to design sets for Ravel’s ballet Daphnis and Chloë, starring Margot Fonteyn, for London’s Royal Opera House. (He re-created the sets for a revival of the show in 2004.)

Voskos (Shepherd) by Craxton, 1984.

Despite the recognition he started to garner in Britain, however, his visits home became more infrequent, and he longed to live permanently in Greece. His style changed radically with the new sense of freedom he found there, as he relished the more relaxed and tolerant social structure, compared with that of Britain. From the 1950s on, Craxton sought and embraced a newfound hedonistic sensuality in his life and art. “All actively gay men—even the most monogamous—were forced into furtiveness and subterfuge in 1950s Britain,” Collins notes in his biography John Craxton: A Life of Gifts.

The artist’s palette brightened significantly; he developed an idiosyncratic graphic style in which figures and forms in nature would be outlined with halo-like auratic highlights redolent of Byzantine icons. In Man Dancing in a Taverna (date unknown) and Reclining Cat (1962), these sinuous, striated markings have an almost art deco feel as they help activate the canvas surfaces. While creating his own unique iconography, Craxton absorbed the stylistic flourishes of contemporaneous works by Picasso and Miró, as well as the compressed spaces, multiple perspectives, and other quasi-cubist elements found in works by his friend Ghika.

From 1960 until the time of his death, Craxton resided in the port town of Chania on the northern coast of Crete. He produced many of his major works there, such as Landscape, Hydra (1963–1967) and Two Figures and Setting Sun (1952–1967), two of the best in this show, and among the artist’s most accomplished works. In the former, almost pointillist touches of blues and greens delineate in an imaginative way the infinite spaces of the Aegean island and its special atmosphere and mood. The latter shows a young man holding an octopus, standing above a recumbent male figure, most likely a victim of the bends, or decompression sickness, often suffered by Greece’s sponge divers, whose lives fascinated Craxton.

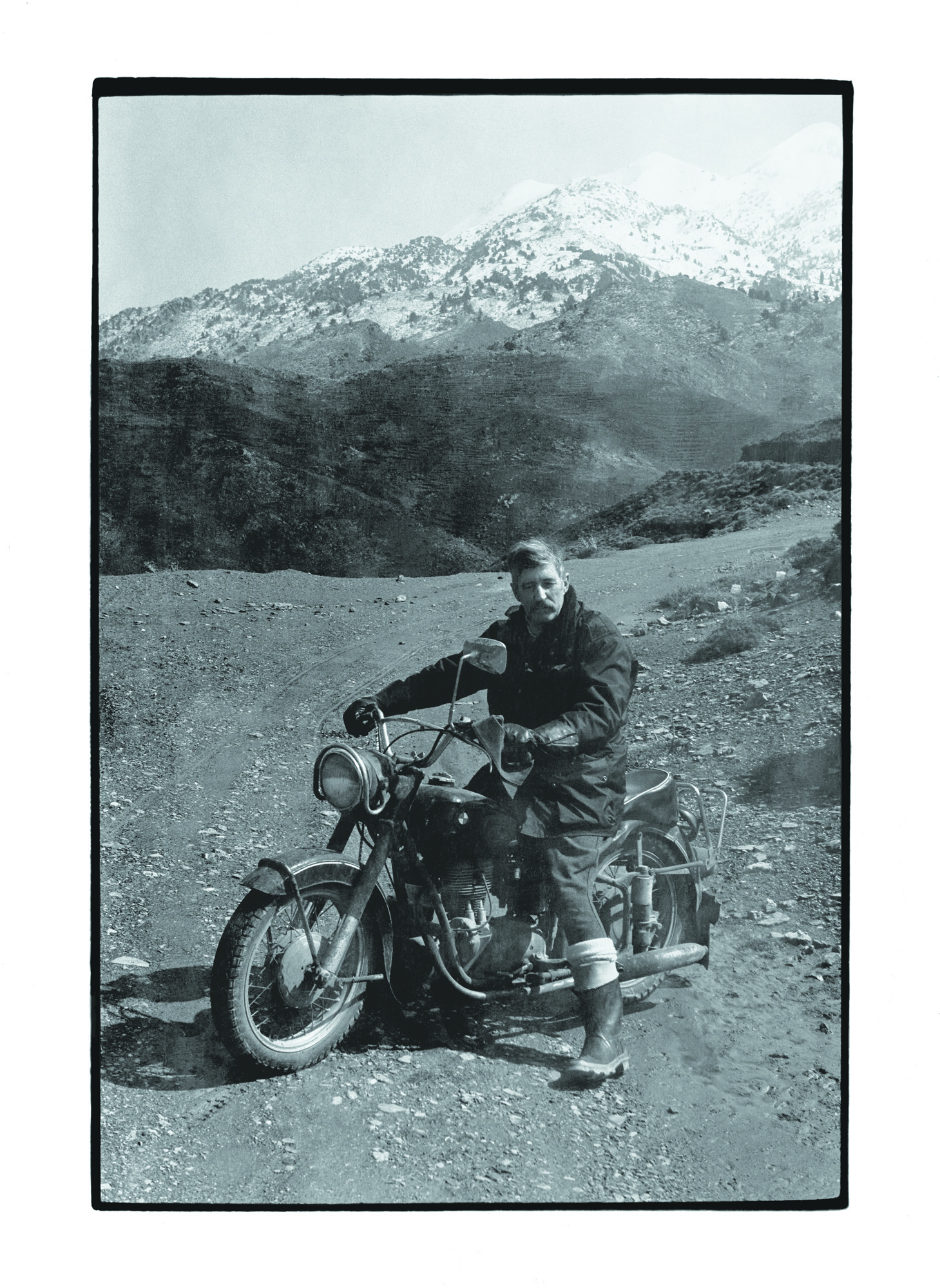

Craxton in the White Mountains of Crete in a photograph by Nicholas Moore (1958–), 1984.

A retrospective exhibition of 151 works held in 1967 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London was roundly panned by the critics, a shock from which Craxton eventually recovered. But thereafter, he no longer sought art-world approval. He returned to his cherished home on Crete, and continued to explore the inimitable world of light and color he had created for his art. A representative later painting, Voskos (Shepherd) of 1984, shows, by means of supple lines and deft, interlocking forms, an idealized image of a Greek youth lassoing a bucking billy goat. The image refers to the capture of a wild bull depicted in Minoan images embossed on gold cups found in a royal tomb in Sparta. It is this extraordinary melding of the ancient and modern in his distinctive compositions that marks Craxton as a true visionary, ripe for rediscovery.

John Craxton: A Greek Soul is currently on view at the Chania Municipal Art Gallery, Crete, until January 31, and travels to the Meşher, Vehbi Koç Foundation in Istanbul, Turkey, from March 21 to July 21. Further venues and dates to be announced.

DAVID EBONY is a contributing editor of Art in America, a columnist for Yale University Press online, as well as the author of numerous artist monographs.