from The Magazine ANTIQUES, July 2011 |

Step into Sharon and Mack Cox’s house in Richmond, Kentucky, and your eye might land first on the large stone fireplace at the end of their open living room. On one side of the hearth is a ballot box thought to have belonged to Cassius Marcellus Clay, an early Southern abolitionist and a founder of the Republican party. Above the fireplace hangs a portrait of General William Henry of Scott County, Kentucky, who fought alongside Isaac Shelby at the pivotal Battle of the Thames in the War of 1812. And below the general is an early nineteenth-century long rifle from central Kentucky.

Free-thinking politician, bigger than life frontier hero, long rifle-the Kentucky myth on a mantelpiece, the same mythology captured by George Caleb Bingham’s image of Daniel Boone crossing the Cumberland Gap that graced the cover of the November 1947 issue of The Magazine Antiques. (1) Devoted to Kentucky decorative arts and architecture, the magazine included a “Shop Talk” column with this observation by Lucy Clay Winn: “If a Kentucky antique dealer should say to you, ‘There was very little furniture made in Kentucky,’ he means to say, ‘I have very little Kentucky-made furniture for sale. My things are to suit a more cultivated taste for hors d’oeuvre and soufflé, and not a taste for hominy, pork, deer meat, and hoe cake.’” (2)

But pull back from the Kentucky myth and look around Mack and Sharon Cox’s house, and a world of Kentucky decorative arts unfolds that is both cultivated and uniquely Kentucky. In other words, it is both hors d’oeuvres and hoe cakes.

In 2002 Sharon and Mack moved south from Lexington to Richmond and built a modern house on a bluff overlooking the Kentucky River. They wanted to furnish the new house with American antiques, and at first acquired an eclectic mix of objects. But they soon found themselves drawn closer to home by the objects made and used by early Kentuckians.

Perhaps it was in their blood. The 1947 Kentucky issue of Antiques included a small advertisement placed by Hallie Coy Cox of Little Eagle Antiques in Richmond, promising objects from “the heart of the blue grass region” (see Fig. 16). She was Mack’s grandmother. Sharon and Mack sold almost all the Eastern Seaboard antiques they had been living with and began to spend every free minute doing research and chasing down great Kentucky objects. “Almost everything I’ve ever done in life I go all in,” Mack says, and so, like the early collector of Kentucky antiques Emma Wilson, who wrote in that same issue of Antiques, they began to “hunt…in shops, at auctions, or on country byways” for great Kentucky pieces. (3)

Mack and Sharon fell in love with the hunt and the research behind every object they pursued. “Sometimes someone e-mails you an image and you just know that you need to drop everything and go after it,” Mack says, recollecting a trip to Florida in a driving snowstorm to look at a purported Clay family cabriole-leg sofa (it wasn’t). An important moment in their collecting came from a meeting with legendary Kentucky collectors Bob and Norma Noe. (4) “They made us think about what a collection is,” Mack says. “Bob and Norma taught us that a lot of folks just accumulate things, but that a great collection is a purposeful collection. It’s a collection in which each object adds to the overall story.”

Those stories come from research, and for Sharon and Mack, detailed research is almost as important as the objects themselves. “There are a lot of things sold as Kentucky, but we want to be sure. Oftentimes you don’t have a lot of time to make a decision, so being prepared with the research is important,” Mack says. The Noes introduced the couple to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts Research Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, which has been collecting data for the past three decades. “We arranged a vacation to go to MESDA and copy data,” Mack says, and when they came home they started adding to MESDA’s information.

Today in their library, along with a card table attributed to Porter Clay (1779-1849) of Woodford County, an assortment of Kentucky stoneware, and a pair of miniature chests made in Bardstown in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, are binders of research notes on every object that has passed through their hands. Numbering in the hundreds, these binders fill almost every closet in the house, and the Coxes’ research files now rival those at MESDA, where Mack currently serves on the advisory board.

While the couple has made a home that is like a museum and research center, it is also a comfortable and inviting place to spend an afternoon sipping a local Ale-8-One soda, or a bourbon and water, while looking out across the Kentucky River and talking about Kentucky decorative arts. In fact, discussing the decorative arts of the Bluegrass State while overlooking the river seems entirely appropriate, for much of Kentucky’s cultural and artistic legacy is connected to its waterways. After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, bateaux and riverboats filled with the state’s produce floated their way south to markets in Natchez, New Orleans, and elsewhere.

Kentucky artisans also worked up and down the rivers. A clock in the Coxes’ living foyer is housed in a case almost certainly by William Lowry who worked in Frankfort, Kentucky, between 1802 and 1810 (Fig. 8). First owned by George Carlyle (1756-1827), an early resident of Woodford County on the Kentucky River, it is attributed to Lowry based on its similarity to a signed example in the Speed Art Museum in Louisville. (5) In 1811 Lowry moved his family downriver to Natchez, where he died in 1873.

Also in the living foyer is a pair of demilune tables from Frankfort (see Fig. 4). They were published in a “Living with antiques” article in this magazine back in 1966, when they belonged to Eleanor Hume Offutt O’Rear (1925-1988), who with her mother, Eleanor Marion Hume Offutt (1894-1955), were among the state’s earliest and most important antiques dealers. (6) The distinctive bellflowers on the table are identical to those on the sideboard in the dining room (Figs. 3, 7), made in Frankfort in the early nineteenth century, possibly for Valentine Stone (1751-1822) or his daughter Kessiah (1788-1862). It stayed with the family for more than a century, until it was sold by a descendant in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the mid-1980s.

On the sideboard are two silver goblets and a ewer with chased and repoussé scenes of tobacco farming that were presented to W. R. Wells of Hart County, for the best hogshead of tobacco, by the State Agricultural Society in 1858. On either side are silver julep cups marked by Samuel Wherritt of Richmond, Kentucky. Indeed, since it is impossible to think about Kentucky without thinking about bourbon (this author’s Kentucky grandmother requires a bourbon and water every night at 5 pm), a late nineteenth-century view of the O.F.C. distillery on the Kentucky River hangs above the sideboard.

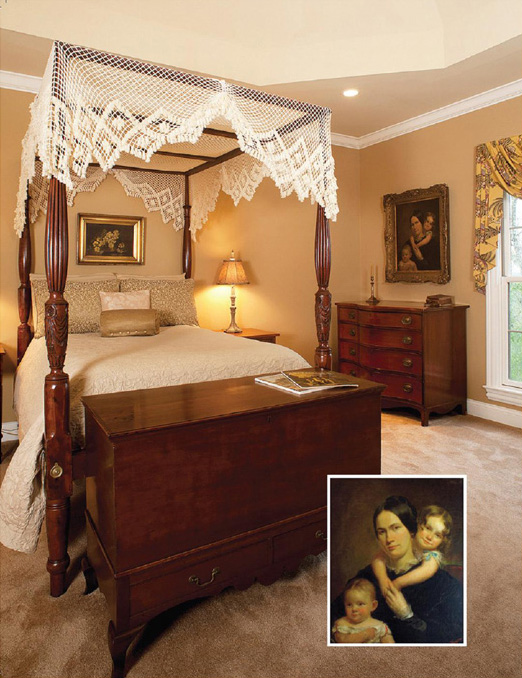

Fig. 14. Portrait of Martha Bell Mitchell Frazer (1816–1903) and daughters Fanny (1846–1878) and Nancy (1848–1917), by Oliver Frazer, c. 1850. Oil on canvas, 27 by 22 inches. Cox photograph.

Kentucky is well known for its inlaid furniture and the Coxes have developed a particular fondness for the “dot and dash” stringing found on at least two groups of early Kentucky furniture. This inlay with lightwood “dashes” interrupted by lightwood “dots” is visually similar to a pattern found in early nineteenth-century Baltimore furniture. Unlike the commercially produced Baltimore stringing, however, that from Kentucky appears to have been made in two parts: first the craftsman created banding of dark and light woods, which he inlaid into the piece of furniture; then he inlaid individual “dots” along the stringing to create the final pattern (see Fig. 15). This more complicated, labor-intensive banding appears to have been employed by a number of craftsmen working near Lexington and Frankfort-as on the demilune tables in the entry hall and the bow-front corner cupboard under the staircase (Fig. 5)-as well as by the craftsman responsible for the Franklin County serpentine-front chest of drawers in the master bedroom.

The high quality of Kentucky inlaid furniture-and its popularity among collectors in the twentieth century-has led to its widespread refinishing. “If you’re going to collect Kentucky you’ve got to consider condition issues and decide what’s important and what’s not,” Mack says. Refinishing has made this a challenge. But the couple was patient. In 2005 they acquired a rare example with its original finish intact (Fig. 12) from one of the most iconic groups of Kentucky furniture-bandy-legged chests of drawers, sugar desks, and blanket chests made in and around Mason County. (7) Likely the work of several interrelated cabinetmakers, the origin of their distinctively shaped legs is not yet fully understood.

Kentucky also has a rich fine arts heritage, and the work of the state’s earliest painters is well represented in the Cox collection. On the stair landing, above a Frankfort serpentine-front chest of drawers with a geometrically inlaid skirt, hangs one of just three extant self-portraits by the native Kentucky portraitist Matthew Harris Jouett (see Fig. 9). Born near Harrodsburg, Jouett studied with Gilbert Stuart (1755-1828) in Boston in 1816. Stuart greatly influenced the way Jouett approached portraiture, offering him a formula that he rarely broke away from. An exception is a small group of children’s portraits, among them the three-quarter length painting of a young Joseph Archibald Logan of Woodford County shown in Figure 17. (8)

advertised her Little Eagle Antiques Shop in Richmond, Kentucky, in The Magazine Antiques in November 1947, p. 306.

The painter Oliver Frazer was born in Fayette County, and was a student of Jouett’s in Lexington. Following Jouett’s death in 1827 he traveled to Philadelphia, and then to Paris, one of the first Kentucky artists to study abroad. After studying with Antoine Jean Gros (1771-1835) he returned to Lexington with a sizable collection of prints and a large number of copies in oil that he had made as part of his studies. In the Coxes’ living room hangs an engraving of Mary Elizabeth Gray, Countess Gray and her daughters-beneath Frazer’s student oil after the now lost painting by Sir Thomas Lawrence (see Fig. 4). Frazer returned to this composition of mother and daughters later in life when he painted his own wife, Martha Bell Mitchell Frazer and daughters Fanny and Nancy. (9) That particularly touching portrait hangs today above the Franklin County inlaid chest of drawers in the master bedroom (Figs. 13, 14).

children in three-quarter view, including eight-year-old Joseph Archibald Logan (b. c. 1816) depicted here with bow and arrow.

Mack and Sharon Cox have spent the last decade collecting the kinds of things Mack’s grandmother once advertised. They are also collecting history. “These objects really bring the history of our state to life for us,” Sharon says. In addition, they generously share their discoveries with the MESDA Research Center, regularly updating the museum’s staff on research related to objects documented in the museum’s field research program. And, alongside fellow MESDA advisory board members Scott Erbes-curator at the Speed Museum-and Clifton Anderson of Lexington, they have worked to increase awareness of Kentucky’s rich artistic legacy through projects like the Kentucky Online Arts Resource, a database of Kentucky decorative arts run by the Speed Museum.

“Everyone who collects is a steward-of the objects in their collection, and of the stories and information connected with those objects,” Mack observes. For this one couple, living with antiques is about sharing their knowledge and passion while preserving objects that, in their words, “have been cherished by, and passed down through, generations in the Bluegrass State.”

1 Now known as Daniel Boone Escorting Settlers through the Cumberland Gap, the painting is in the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum of Washington University in Saint Louis. 2 Lucy Clay Winn, “Shop Talk: Antiques Within the Reach of All…,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 52, no. 5 (November 1947), p. 316. 3 Emma Wilson, “Antiques Ubiquitous…,” ibid., p. 318. 4 The Speed Art Museum in Louisville has produced a series of oral history interviews with the Noes that are available on YouTube and through the Kentucky Online Arts Resource Blog at koar.org. 5 Acc. 2004.1.3 at the Speed Art Museum via koar.org. 6 Eleanor Offutt O’Rear, “Living With Antiques: Stony Lonesome in Kentucky,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 89, no. 6 (June 1966), p. 854. 7 Marianne P. Ramsey and Diane C. Wachs, The Tuttle Muddle: An Investigation of a Kentucky Case-On-Frame Furniture Group (Headley-Whitney Museum, Lexington, Ky., 2000). 8 Estill Curtis Pennington, Lessons in Likeness: Portrait Painters in Kentucky and the Ohio River Valley, 1802-1920 (University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2011), pp. 13, 172-173. 9 Estill Curtis Pennington, Kentucky: The Master Painters from the Frontier Era to the Great Depression (Cane Ridge Publishing, Paris, Ky., 2008), pp. 59-62.

DANIEL KURT ACKERMANN is the associate curator of the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts at Old Salem Museums and Gardens in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.