from The Magazine ANTIQUES, November/December 2011

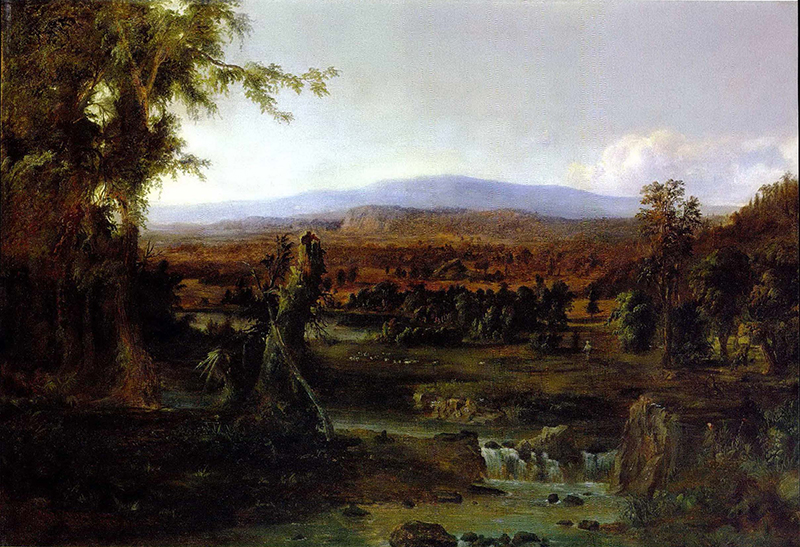

Fig. 1. The Shepherd Boy (also known as Landscape with Shepherd) by Robert S. Duncanson (1821-1872), 1852. Signed and dated “R.S. Duncanson/1852” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 32 ½ by 48 ¼ inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Hanson K. Corning by exchange.

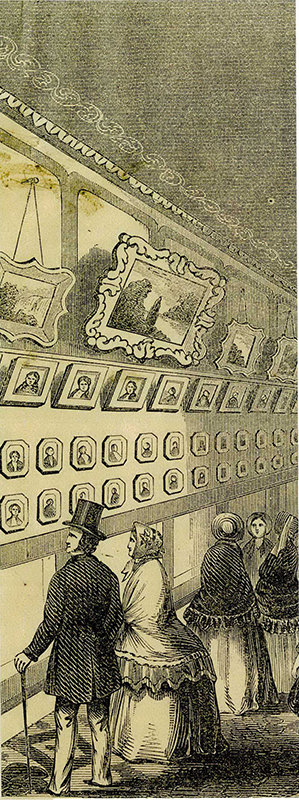

In 1854 Gleason’s Pictorial, the popular, nationally circulated magazine out of Boston, published an article promoting the lavish “Daguerrian Gallery” established in Cincinnati by James P. Ball (Fig. 6), lauding his images as “unsurpassed by any in the Union.”1 In fact, Ball’s Gallery (see Figs. 2, 4) was not so unusual. Mathew Brady’s popular and equally elaborate establishment had flourished in New York since 1844. Yet Ball’s Gallery was, in the eyes of the eastern press, exemplary of the cultural advancement of Cincinnati, a city that when Ball began a decade earlier was “in a very low state indeed.” The fact that this major national voice credited Ball with arousing “a spirit in the profession which has…brought within so short a time the Daguerrean art to so much perfection”2 aroused considerable interest.

The story only obliquely alluded to the fact that Ball was a “free colored person,” in the polite parlance of the period, mentioning that his “struggles were many and great.” Seizing the opportunity to promote the work of a free black artist, a number of abolitionist and black publications also ran the story.3

Gleason’s article also featured another Cincinnati artist of color, the landscape painter Robert S. Duncanson (Fig. 5). The article referred to Duncanson by his last name only-perhaps on the assumption that the magazine’s readership would be familiar with him. It mentioned that his paintings such as The Shepherd Boy (Fig. 1) hung on the walls of Ball’s Gallery and that they ranked “among the richest productions of American artists.” Working next door to each other on fashionable Fourth Street in the central business district Duncanson and Ball were at the heart of Cincinnati’s cultural life; the painters James Henry Beard, John Cranch, Godfrey Frankenstein, and the Academy of Design were all within walking distance. By 1850 Duncanson had formed part of a triumvirate of Ohio River valley artists with William L. Sonntag and T. Worthington Whittredge. Together they crafted a distinctive regional branch of the national landscape painting movement. Duncanson had also executed a monumental suite of landscape murals for the estate of Nicholas Longworth (1782-1863), one of Cincinnati’s prominent citizens, who praised the artist as “one of our most promising painters.”4 After Sonntag and Whittredge left for New York, Duncanson was the sole bearer of the standard for landscape painting in the region. In 1861 the Cincinnati Daily Gazette acknowledged Duncanson’s position, writing that he had “long enjoyed the enviable reputation of being the best landscape painter in the West.”5

Gleason’s and the other periodicals that ran the “Daguerrian Gallery”story heralded the cultural growth of Cincinnati as evidence that American civilization was demonstrably progressing over the western wilderness. This was not hyperbole; a unique confluence of economic, political, and social factors in Cincinnati made it possible for Duncanson and Ball to assume prominent cultural positions in the city and to attract other African-American artists, establishing an active and prosperous enclave of free colored artists.

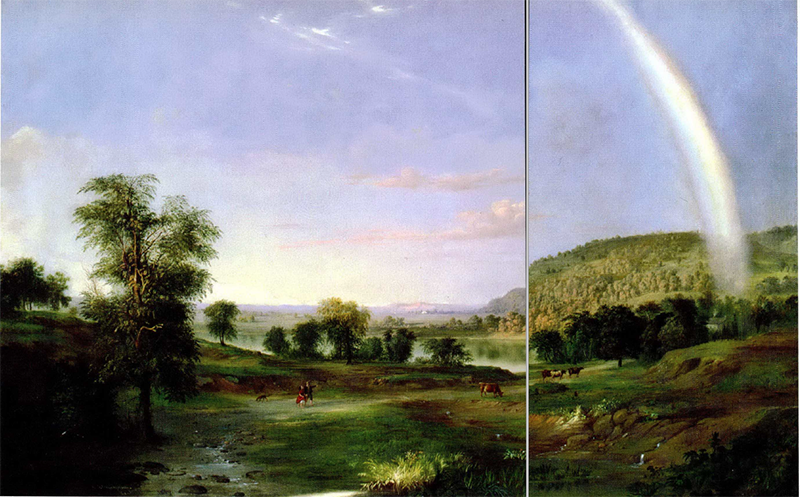

Fig. 3. The Rainbow by Duncanson, 1859. Signed and dated “R. S. Duncanson 1859” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 30 by 52 ¼ inches. Smithsonian American ArtMuseum, Washington, D. C., gift of Leonard Granoff.

To begin with, the city’s site on the Ohio River, at the crossroads of the major east to west transportation routes and on the border between the North and the South, meant that it linked the various regions of the country geographically, economically, and culturally. As the nation moved westward the city experienced explosive economic and population growth, becoming the leading economic center of the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains by 1850. The expanding economy created a class of wealthy patrons essential to supporting a thriving arts culture. Indeed, Cincinnati produced such artistic and literary figures as Hiram Powers, Lilly Martin Spencer, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Despite the fact that many of them eventually left Cincinnati for the east and Europe, the city earned the popular appellation the “Athens of the West.”

Cincinnati was also a stronghold of abolitionism and served as a center for free people of color, who were attracted by the opportunities it offered. Despite the pervasive existence of racial discrimination, the city’s complex social and cultural dynamics contributed to the development of a thriving African-American community. Although situated in a northern state where slavery was illegal, the city also had close social and economic ties to the southern states. In 1807 a series of “black laws” had required free blacks to register and post a five hundred dollar bond to settle in Ohio. At the time of Ball and Duncanson’s moves to Cincinnati in the 1840s, the city experienced a series of pro-slavery riots, the most severe in the nation. The violence galvanized antislavery activists who forced the state to repeal its black laws in 1849, providing free blacks legal protection similar to that accorded to whites, and offering educational opportunities with state-sponsored education.6

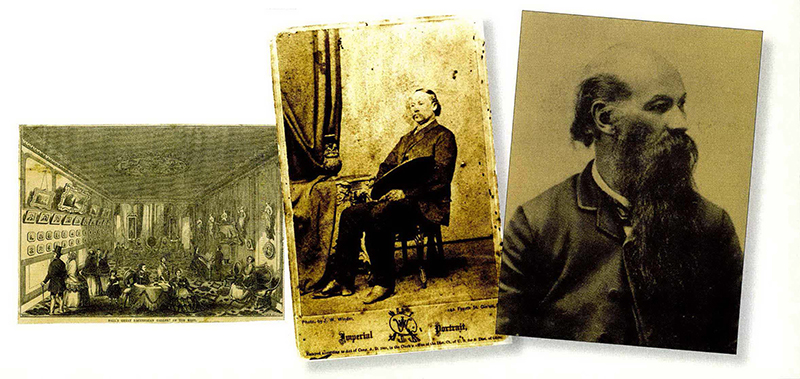

Fig. 4. Ball’s Great Daguerrian Gallery of the West, engraving in Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, vol. 6, no. 13 (April 1, 1854). Cincinnati Historical Society, Ohio.

Fig. 5. Robert S. Duncanson by J. W. Winder, c. 1868. Inscribed “Photo by J. W. Winder” and “142 Fourth Street, Cin’ati, O.” under the image. Daguerreotype. Monroe County Historical Museum, Monroe, Michigan.

Fig. 6. James P. Ball (1825-1904) in a photograph from his obituary in the Seattle Republican, May 20, 1904. Courtesy of the Cincinnati Historical Society.

Because of these factors a small black middle class emerged-overwhelmingly mulatto-of clerks, shopkeepers, and businessmen. They established churches, schools, and benevolent societies, and it is clear from the contemporary black press that their goals were to assimilate into the larger American community and to participate in the American dream.7 The Colored American advocated that its readers strive to be “worthy” in order to participate in “polite and elevated society.”8 And, Cincinnati’s black middle class took great pride in doing just that. John Mercer Langston, an African-American abolitionist lawyer who had experienced the destructive riots of 1841, complimented Cincinnati’s blacks: “If there ever existed in any colored community of the United States, anything like an aristocratic class of such persons, it was found in Cincinnati….In fact the entire negro community of the city gave striking evidences, in every way at this time, of its intelligence, industry, thrift and progress; and in matters of education and moral and religious culture, furnished an example worthy of the imitation of their whole people.”9 The careers of J. P. Ball and Robert S. Duncanson exemplified these social and moral goals.

Duncanson had moved to Cincinnati in 1841 to pursue a career as an artist. After working for most of the decade as an itinerant painter, he was motivated to change his practice in 1848 upon seeing Thomas Cole’s Voyage of Life series (1842, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D. C.) on display at Cincinnati’s Western Art Union. The experience prompted him to focus on landscape as a metaphor for expressing American ideals (see Fig. 3). But while Duncanson emulated the romantic landscape style and didactic mission of Cole and Asher B. Durand, he rarely created the kinds of dramatic and sublime views of the wilderness for which those artists are known, preferring instead more pastoral and picturesque scenes that he considered emblematic of the ideals of both the country at large and the free black community within it.10

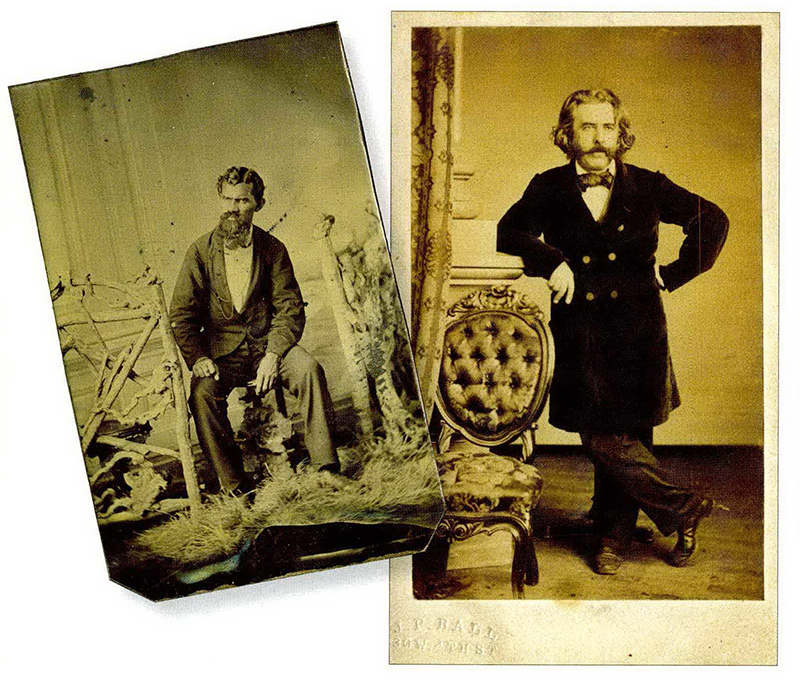

Fig. 8. Thomas D. Jones (1811- 1881) by Ball, c. 1862. Stamped “j. p. ball/30 w 4th st” on mat at lower left. Carte de visite albumen print, 4 by 2 ½ inches. Cincinnati Historical Society.

Ball settled in the city in 1845 as a daguerreotypist, a trade he had learned in his native Virginia. Like Duncanson, he plied his trade on the road before opening a gallery in 1851. In 1853 he moved into the expansive rooms on Fourth Street seen in the Gleason’s Pictorial engraving. Like Brady he outfitted his studio as an art gallery complete with paintings, engravings, and images of famous people. His was the city’s prestige establishment for portraits of prominent citizens done in the grand manner (see Fig. 8). Ball sometimes gave his portraits the finish and appearance of paintings by adding brushed colors to the black-and-white images. Duncanson had the responsibility of coloring the daguerreotypes, painting backdrops, retouching negatives, and advising on the posing of sitters.11 Ball and Duncanson’s colored photographs were “the town talk. Everyone pronounces them life-like and artistic, and creditable to the skill of Mr. Ball, as well as to the magic pencil of R.S. Duncanson, who does the coloring.”12 Unfortunately, no colored daguerreotypes survive to show the results of their collaboration.

In the 1850s, during the height of abolitionist fervor in the city, Ball created a monumental antislavery panorama, Ball’s Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade. Capitalizing on the popularity of scenic panoramas, Ball’s six-hundred-yard-long panorama traveled to theaters across the country, where audiences watched the pictures unfurl as a narrator guided them through episodes in the slave trade beginning with capture in Africa, the transatlantic passage, slave markets, and escape up the Mississippi to freedom in Canada. Although the panorama is lost, the surviving script confirms Ball’s mission to condemn the hypocrisy of the United States as “the land of the free, and the home of the slave.” The script devotes a section to Cincinnati, where Ball commends the “liberal spirit of Cincinnatians….The Anti-Slavery people courageously faced the storm of popular indignation… [and] free speech triumphed.”13

Fig. 9. View of Cincinnati, Ohio from Covington, Kentucky by Duncanson, c. 1851. Oil on canvas, 25 by 36 inches. Cincinnati Historical Society.

Ball modeled his panorama on two from 1850 based on the narratives of the escaped slaves Henry Box Brown and William Wells Brown.14 He distinguished his panorama by advertising that it was “painted by Negroes.” This certainly refers to Duncanson, the principal artist working in Ball’s Gallery at this time, as well as to the other members of his large staff of African-American artists and daguerreotypists.15

Ball and Duncanson’s reputations lured a number of young artists of color to Cincinnati where they apprenticed, worked, and boarded with the senior artists. Living with Duncanson was a mulatto man from Virginia named George W. Wilson, while James Goings from Ohio lived with the Ball family.16 These young men along with several others who were also registered as artists in the census, formed the core of the black art community in Cincinnati. Interestingly, most of them migrated from Virginia or were descended from Virginia families, as were the majority of free blacks in Cincinnati.17 The result was a tight, mutually supportive cultural network.

Fig. 10. Land of the Lotus Eaters by Duncanson, 1861. Signed and dated “R. S. Duncanson/1861” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 52 ¾ by 88 inches. Collection of the Royal Court, Sweden; photograph by Alexis Daflos.

Unfortunately, Cincinnati’s burgeoning black artistic community was short lived. By the end of the 1850s, on the eve of the Civil War, racial tensions were running high in the city and pro-slavery sentiment was directed at the free black population. After Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, “Negrophobia” triggered by the fear of mass migrations of African Americans from the South, gripped Cincinnati, making it especially tense for the black residents.18 Nature made its own contribution to the fate of Cincinnati’s free black community in May 1860, when a catastrophic tornado demolished Ball’s Gallery.

Duncanson responded to the grave political climate by creating Land of the Lotus Eaters, his most ambitious easel painting (Fig. 10). Inspired by The Odyssey, Duncanson’s Land of the Lotus Eaters offered a plea for peace in a canvas where dark-skinned figures cross the river to white soldiers. The painting went on public display in the city as the war erupted. As the war dragged on and its outcome looked bleak, Duncanson left Cincinnati in 1863. After four years of traveling through Canada and Europe, he returned to Cincinnati to discover a city chastened by the realities of civil conflict and hardened in its discrimination against anyone with a drop of African blood. Although Ball and Duncanson maintained their positions as preeminent artists, the war destroyed the community of artists of color that had briefly flourished with them.

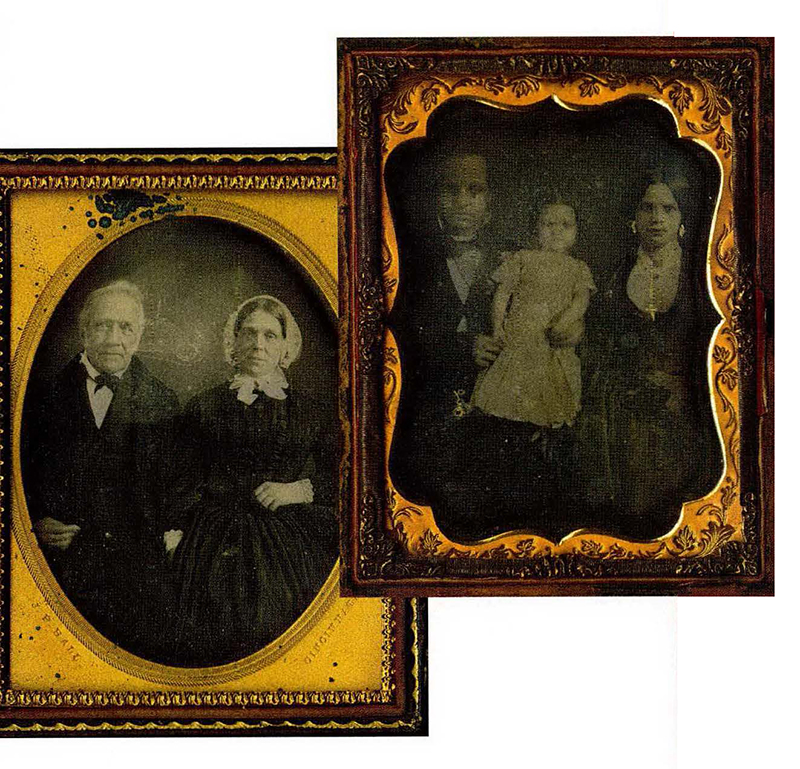

Fig. 11. Portrait of an Unidentified Man and Woman by Ball, c. 1850s. Daguerreotype, 4 ¼ by 3 ¼ inches. Cincinnati Historical Society.

Fig. 12. Portrait of Alexander Thomas and Family, wife Eliza and daughter Catherine, by Ball, c. 1854. Daguerreotype, 4 ¼ by 3 ¼ inches. Cincinnati Historical Society.

1 “Daguerrian Gallery of the West,” Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, vol. 6, no. 13 (April 1, 1854), p. 208. 2 Ibid. 3 It was reprinted in the Frederick Douglass’ Paper, May 5, 1854, p. 1, and the Provincial Freeman (Windsor), June 3, 1857, p. 2. 4 Nicholas Longworth to Hiram Powers, June 20, 1852, Cincinnati Historical Society, Ohio. 5 Cincinnati Daily Gazette, May 30, 1861, p. 2. 6 Carter G. Woodson, “The Negroes of Cincinnati Prior to the Civil War,” Journal of Negro History, vol. 1, no. 1 (January 1916), pp. 2-3, 16. 7 Several studies discuss the social opportunities and stratification within the antebellum African-American community. See V. Jacque Voegeli, Free But Not Equal: The Midwest and the Negro During the Civil War (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1967); Ira Berlin, Slaves Without Masters: The Free Negro in the Antebellum South (Pantheon Books, New York, 1974); James O. Horton, “Shades of Color: The Mulatto in Three Antebellum Northern Communities,” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, vol. 8, no. 2 (July 1984), pp. 37-59; Race and the City: Work, Community, and Protest in Cincinnati, 1820-1970, ed. Henry Louis Taylor Jr. (University of Illinois Press, Urbana, 1993); Henry L. Taylor, “On Slavery’s Fringe: City-Building and Black Community Development in Cincinnati, 1800-1850,” Ohio History, vol. 95 (Winter-Spring 1986), pp. 5-33, and his companion article “Spatial Organization and the Residential Experience: Black Cincinnati in 1850,” Social Science History, vol. 10, no. 1 (Spring 1986); Leonard P. Curry, The Free Black in Urban America 1800-1850: The Shadow of the Dream (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1981), p. xix. 8 Colored American, December 2, 1837, quoted in Frankie Hutton, “Social Morality in the Antebellum Black Press,” Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 26, no. 2 (Fall 1992), p. 73. 9 John Mercer Langston, quoted in William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek, “Culture and Kinship: John Mercer Langston in Cincinnati: 1840-1843,” Queen City Heritage: The Journal of the Cincinnati Historical Society, vol. 47, no. 1 (Spring 1989), p. 4. 10 For more on Duncanson see my publications, The Emergence of the African American Artist: Robert S. Duncanson, 1821-1872 (University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 1993) and Robert S. Duncanson: “the spiritual striving of the freedmen’s sons” (Thomas Cole Historic Site, Catskill, New York, 2011). 11 In the 1853 Cincinnati business directory Duncanson listed his profession as “daguerreotype artist,” not painter. 12 Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, August 29, 1857, p. 3 and September 6, 1857, p. 3. 13 Ball’s Splendid Mammoth Pictorial Tour of the United States, Comprising Views of the African Slave Trade (Cincinnati, 1855), pp. 18, 46-47. 14 Henry Box Brown’s Mirror of Slavery (Boston, 1850) and William Wells Brown’s Original Panoramic Views of the Scenes in the Life of an American Slave, from his birth in slavery to his death or his escape to his first home of freedom in British soil (London, 1850). 15 Advertisement in the Liberator cited in Juanita Marie Holland, “Reaching Through the Veil: African-American Artist Edward Mitchell Bannister,” in Edward Mitchell Bannister, 1828-1901 (Kenkeleba House, New York, and the Whitney Museum of American Art at Champion, Stamford, Conn., 1992), p. 22. 16 United States Census, 1860, Cincinnati, Ohio, p. 64. 17 Joe William Trotter Jr., River Jordan: African American Urban Life in the Ohio Valley (University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1998), pp. 26-27. 18 W. Sherman Jackson, “Emancipation, Negrophobia and Civil War Politics in Ohio, 1863-1865,” Journal of Negro History, vol. 65, no. 3 (Summer 1980), pp. 250-260.

JOSEPH D. KETNER II holds the Foster Chair in Contemporary Art and is Distinguished Curator-in-Residence at Emerson College, Boston. He is an authority on Robert Duncanson and also writes on modern and contemporary art.