What first strikes the eye about the Midwest is its horizontality. The abstract simplicity of the landscape—hardly a landscape at all—spooked the Hudson River school painters, who in the nineteenth century leapfrogged over the mundane middle of the United States to paint the peaks of the West and South America. Almost every portraitist of “flyover country” before and since has emphasized its people or animals, as if to apologize for the region’s embarrassing lack of topographical content. They seem to have forgotten that, as any beachgoer knows, emptiness has a sublimity all its own. But even by describing the prairie as empty one succumbs to stereotypes—”plant blindness,” as former Illinois natural areas ecologist Randy Nyboer would put it. Wayfinding amidst the seeming infinite variety of herbage, one needs the savvy of a naturalist and the soul of a poet. Painter Philip Juras finds both registers—and doesn’t forget the virtues of the panorama—in his exhibition The Long View: Prairie Paintings from Illinois Nature Preserves at the Illinois State Museum’s Lockport Gallery, which pictures remnant prairies stewarded by the Illinois Nature Preserves Commission over its sixty-year history.

Juras’s project begins with longing. What he seeks is Arcadia. He is at something of an advantage over seekers of yore, in that his Arcadia was a historical place: North America’s pre-settlement tallgrass prairie. It’s an ecosystem that, long before Juras was born, was boxed out of his native state of Georgia by encroaching woodlands. And so, like the multitude of flowers and birds named Carolina-this and Virginia-that, he made his way northwest to the Prairie State.

Despite its nickname, Illinois today supports a meager two thousand out of what was originally more than 20 million acres of prairies—hardly the vaunted “ocean of grass” described with such fear and awe by nineteenth-century travelers. What remnants avoided the plow and the bulldozer are patchy and far-flung, showing up along railroad right-of-ways, on slopes too steep to farm, or in the pioneer cemeteries whose ancient, crumbling headstones rise Ozymandian in the midst of teeming flora. That these patches survive at all is thanks in many cases to neglect. But in recent decades, as the result of aggressive restoration efforts, some of these remnants are putting on acres, mushrooming into former farmland bought up by international organizations like the Nature Conservancy, and the Illinois-based Natural Land Institute and Citizens for Conservation. At the largest sites, such as the sprawling Nachusa Grasslands in Lee and Ogle Counties and Spring Lake Preserve in Cook, it’s possible, squinting, to imagine paradise regained, somewhere off in the distant future.

Juras is just such a squinter. And to bring the future into even sharper focus, he allows himself to deviate in subtle ways from optical reality, erasing a farmhouse here, extending a savanna to the horizon there. His painter’s tactics parallel the work of restorers and conservationists, who, even while dreaming of some untouched Eden, may plant, prune, and otherwise arrange nature according to a law that is man-made. In painting the law is aesthetics; in restoration, ecology. And in Juras’s work the two form a circle, each feeding into and informing the other.

A “shift happens as the wetter soils of the plain, which lie just a few feet behind us in this view, transition to the drier soils of the dune ridge located immediately before us,” he writes about Foley Sand Prairie, painted in Lee County. “Moisture-loving prairie cordgrass, with its long arcing leaves in the lower right foreground gives way to big bluestem a little higher on the slope as the soil moisture decreases. In turn, the big bluestem’s warm-colored vertical stalks rise toward the horizon line and blend into the reddish tint of little bluestem, the prominent grass occupying the dry ridge top. It’s a shift from wet to dry, from coarse to fine, and from green to red.”

Such niceties of the botanical milieu are captured with confident, short-stroking brushwork by Juras. In Prospect Cemetery Prairie the characteristic aspect and attitude of all the different plants in a black-soil remnant are reproduced with such truthfulness that even the timidest naturalist wouldn’t scruple to name what’s in bloom (butterfly weed, black-eyed Susan, leadplant, New Jersey tea, among others). Likewise in the painter’s Beadles Barrens or Shoe Factory Road Prairie one becomes aware of just how many combinations of viridian, green lake, cadmium, and sap green can be found in a meadow’s verdure. Each species has its own hue, which realization supplies, as it were, a drive-by botanical lesson.

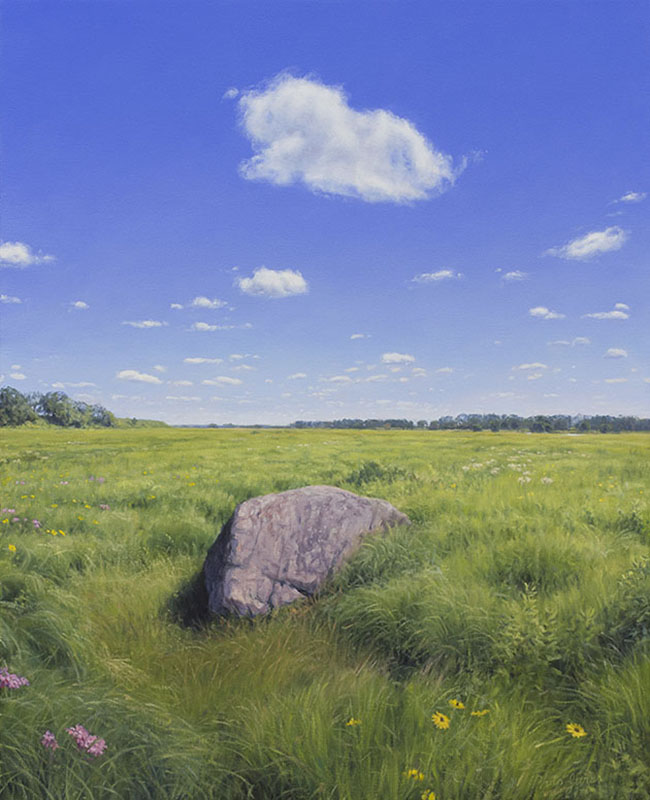

History and geology too have a part to play. Considering the Prospect Cemetery Prairie, a five-acre memorial to frontier burials in Ford County, Juras draws attention to the fact that the broad-leaved and woody plants to be found growing today contradict the accounts of settlers who—perhaps paying no better attention than most Illinois visitors—recorded Indian- and switchgrass and big bluestem. For Will County’s Lockport Prairie, Juras recounts how the valley was formed by glacial meltwaters seeping from the prehistoric Lake Chicago, which left behind “steep bluffs, exposed dolomite bedrock, gravel bars, and the occasional boulder,” such as the one at the center of his painting Glacial Erratic.

Such attunement not only to the visual composition of the prairie, but also to the patterns of life that underlay and run through it serves to redress the two-century-old insult of the Hudson River school—and using that cohort’s own tricks. One must recall that, before the 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species, American art was defined by the confluence of romanticism, Christianity, and science, which together conjured an image of creation brimming with immanence and interconnectedness. It was in that line that Frederic Edwin Church churned out room-sized tableaux of Ecuadorean volcanoes that mix fastidious observation with poetic license in crescendoing paeans to the natural world, and it would also color Albert Bierstadt’s reception of the American West. Juras can claim artistic inheritance from both of these men, particularly the latter. But it is not Bierstadt per se who most directly anticipates him, but the pattern that the German artist was part of—the fact-gathering ethos of the painters, draftsmen, and particularly the photographers who accompanied the government-funded survey parties westward in the decades immediately before and after the Civil War.

Like Juras, the survey photographers can appear to efface themselves, in order to let the landscape speak. It is true that Juras’s work, despite what it shares visually and methodologically with the efforts of those witnesses, does so to opposite effect, cataloguing and mapping the natural world not as part of some conquering vanguard, but as rearguard. It is a record of our retreat. And yet it is also true that it is only in the work of the best of these surveyor-artists, and particularly photographer Timothy O’Sullivan—alone among his cohort to encounter and visually solve a landscape approximating pre-settlement Illinois’s—that we find, as the critic Andy Grundberg noted, that hinge between a pre-modern view of nature attuned to the needs of man, and our contemporary alienation from it.

In Juras’s work this “modern” content is very carefully hidden. Indeed, it appears much more clearly in the canvases of his best-known regionalist forebears, Dale Nichols, Grant Wood, or John Rogers Cox, whose sharp-edged stylistics serve to create distance between viewers and red tractor or plowed acre. That sort of treatment, as it happens, concerns matters rather of painting than of place, and in comparison Juras can seem to pull his punches. His framing is almost always conservative, little different from how a 50 millimeter camera lens sees the world; he makes use of extremities neither of contrast, scale, nor color. Even when, in hurried plein-air sketches, Juras turns his attention to the remnant-wide fires lighted to burn off invading saplings and exotic weeds and stimulate the growth of native species, the impastoed masses of flame steer well clear of that primordial horror that has always been the sublime grace of wildfires.

But what may look like a missed aesthetic opportunity is germane to Juras’s objectives. The play of impressions upon the human retina is an oft-undervalued phenomenon, filtered as it is through a particularly human sensibility. By painting a prairie that does indeed look like that, and pointing up the beauty of the familiar, Juras creates the conditions for a new appreciation of the Midwest—and an ethic for right-living on the land—in the manner of artists of the White Mountains and Catskills, the Rockies, Sierras, and arid southwest. Besides, in a region purged of its (always limited) horrors by nearly two centuries of domestication, and which is very often beautiful, occasionally picturesque, and far less frequently sublime, the conventionality and, yes, prettiness of Juras’s style is hardly out of place.

Yet despite Juras’s conservative visual style, it is undeniable that certain of his canvases do reproduce the sensation of the prairie, in all its complexity. Indeed, looking again at some of these—and others unfortunately absent from Lockport, such as the fantastic Late Afternoon on the Grand Prairie of Illinois c. 1491—it is even possible to detect shades of that exotic moonscape that struck fear in early settlers. In his sketch of the Sunbury Railroad remnant in Livingston County Juras pushes the frame down. Deep down, until the glorious profusion of grey-headed coneflowers, milkweeds, and rattlesnake master almost succeed in shouldering the civilizing row of corn out of the top of the picture. He must have stood right in their midst, stems and leaves wrapping around his legs, as if willing to pull him down into their blind, incessant struggle for light and life. This is not terrain that can be visually summarized from a distance, but must be dealt with on a plant-by-plant basis, a realization almost nauseating for the labor it portends, the lifetime of discoveries yet to be made among roots that reach deep underground, into the rich glacial drift that remembers bison and Indians, homesteaders and Big Agriculture, and all that came before as well.

There is, of course, something Orphean about the yen to see again what has passed away. And yet, if regaining paradise—as symbolized by the large-scale restoration of the tallgrass prairie—is truly in the offing, even if only in the far-off future, won’t that be like returning from underground with Eurydice alive again?

Philip Juras | The Long View: Prairie Paintings from Illinois Nature Preserves • Illinois State University Lockport Gallery • to October 21 • illinoisstatemuseum.org