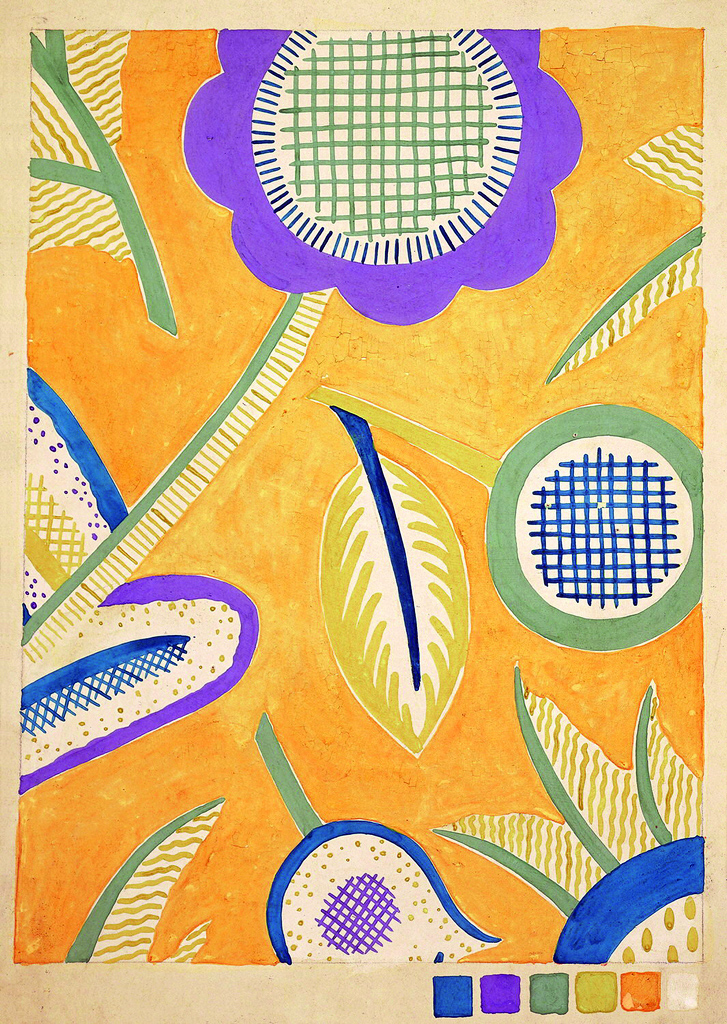

Fig. 1. Untitled painting by Ilonka Karasz (1896–1981), c. 1920. Signed “i. karasz” at lower left. Casein or gouache on wove paper with shell gold, mounted on wove paper, 3 5/8 inches square. Collection of the Portas family; photograph by Michael McKelvey, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art, Athens.

Fig. 2. Photograph of Karasz attributed to Nickolas Muray (1892–1965), c. 1920. Portas family collection.

Even in the bohemian enclave of Greenwich Village, where she settled when she emigrated from her native Hungary in 1913, Ilonka Karasz drew attention. Her younger sister Mariska Karasz described her allure: the “deep black eyes” and the “Mona Lisa style” black hair “inclined towards blue,” the “seriousness,” and the way people often called Karasz a gypsy because of her colorful clothes, and how “the strains of soft music quake[d] her emotions.”1

She was intimidating and captivating, reclusive and passionate. Artists Winold Reiss and Eugene Speicher painted portraits of her; Nickolas Muray photographed her often (see Fig. 2); the small-time publisher and self-styled Village eccentric Guido Bruno touted her as “the Hermit Painter”; and Vanity Fair included her in a feature on the muses of “New York’s So-Called Quartier Latin.”2

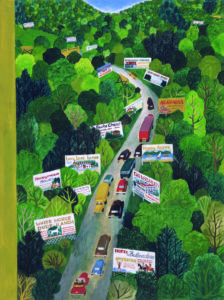

Fig. 4. Cover of the New Yorker by Karasz showing the New York World’s Fair, September 2, 1939. Signed “karasz” vertically at lower left. Offset lithograph on paper, 11 7/8 by 8 ¾ inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum.

Fig. 3. Plate designed by Karasz and manufactured by Buffalo Pottery, Buffalo, New York, c. 1935. Marked “buffalo/ china/ lamelleware/ design/ karasz” on back. Glazed earthenware; diameter 9 inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, gift of Ashley and Mark Callahan in memory of Solveig Cox.

Best known for her cover illustrations for the New Yorker—she made 186 of them between 1925 and 1973—Karasz, in a career spanning six decades, created paintings, woodcuts, lithographs, illustrations, batiks, textiles, wallpapers, silver, ceramics, furniture, interiors, nurseries, book jackets, Christmas cards, and maps. This impressive diversity led collectors and curators to a fractured knowledge of her career: her silver and furniture are avidly acquired by those interested in American modernism, her rare fabrics treasured by textile curators, and her railroad china sought after by train aficionados. An exhibition that opened this past fall at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, however, provides a valuable opportunity to examine a wide range of her work and to appreciate how, even as she moved between projects and mediums, she maintained a distinctive modern aesthetic informed by a strong sense of geometry, a skillful use of color, and a love of folk art and nature.

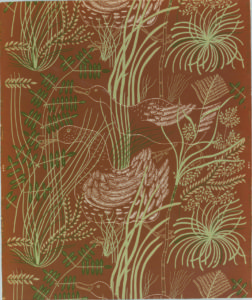

Fig. 5. Ducks and Grasses wallpaper by Karasz, manufactured by Katzenbach

and Warren, New York City, 1948. “‘ducks and grasses’ designed by ilonka

karasz” and “katzenbach and warren” printed in the selvedge. Screen

printed on paper, 27 5/8 by 30 inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, gift of Katzenbach and Warren, Inc.

Fig. 6. Two chairs by Karasz, c. 1928. Unidentified wood; left: height 30, width 21 3/8, depth 19 ¾ inches; right: height 27 5/8, width 17 1/8, depth 22 1/8 inches. Left: whereabouts unknown. Right: Portas family collection; McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Portas family and the Georgia Museum of Art.

Karasz’s covers for the New Yorker evolve from dynamic modern depictions of urban life to enchanting, peaceful images of leisure activities in the city or vacation spots in the country. These covers are both significant cultural artifacts that graced millions of coffee tables across the country and windows into her daily life, recording details like family picnics or the insects and flowers in her garden. Many show scenes around Brewster, New York, where she and her husband, Willem Nyland, a Dutch-American chemist and pianist, moved after they married in 1920, though she maintained an apartment in New York City. Karasz rarely wrote about her life or work, so these views of her experiences create an important personal chronicle in a surprisingly public format.

Fig. 7. Candlestick and bowl designed by Karasz and manufactured by Paye & Baker, North Attleboro, Massachusetts, c. 1928. Stamped “e.p.n.s./ p & b” on side of one foot on each, “562 ik” on bowl, and “557 ik” on candlestick. Electro-plated nickel silver; candlestick height 3 3/8, diameter 5 3/8 inches; bowl height 1 7/8, diameter 3 1/4 inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum; museum purchase, Decorative Arts Association Acquisition and General Acquisitions Endowment Funds.

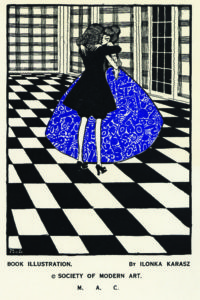

Her desire to promote modern design surfaced in the teens, when she helped establish the Society of Modern Art, publisher of the Modern Art Collector—a magazine that ran from 1915 to 1918 and allowed Americans to stay in touch with modern European design during World War I.3 Her contributions reflect the influences of the Wiener Werkstätte and Hungarian peasant art, both prominent in Budapest, where she studied textiles and graphics at the Hungarian Royal School of Applied Arts.4 During these early years, she also participated and won awards in textile design contests, sponsored by the daily trade publication Women’s Wear, that encouraged American design and American manufacturers while involving much immigrant talent.

Fig. 9. Original cover design by Karasz for the New Yorker, published December 15, 1945. Signed “karasz” at lower left. Gouache or casein with incised lines on illustration board, 16 1/8 by 12 1/4 inches. Portas family collection; McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.

Fig. 8. Original cover design by Karasz for the New Yorker, published June 14, 1947. Signed “karasz” at lower left. Watercolor and gouache on watercolor board, 16 ½ by 12 ¼ inches. Portas family collection; McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.

By the late 1920s, Karasz emphasized modern interiors and objects. She continued designing textiles and created several patterns for silver-plated wares for Paye & Baker of North Attleboro, Massachusetts, that are strikingly modern in their geometric simplicity (Fig. 7). In the summer of 1928, the influential decorating magazine House Beautiful featured photographs and descriptions of both her home in Brewster—an ever-expanding structure she built with her husband, filled with an eclectic mix of modern furniture she designed and textiles and pottery from around the world—and her studio in New York—also appointed with modern furniture of her design as well as interesting accents with amethyst and ultramarine mirror glass.5

Fig. 11. Serenade wallpaper by Karasz installed in the bedroom of William Katzenbach, in an undated photograph. Portas family collection.

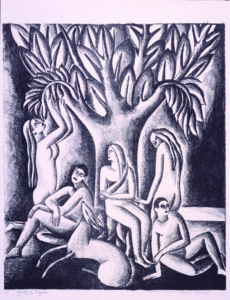

Fig. 10. Group of Figures by Karasz, c. 1921. Signed “Ilona Karasz” at lower right; numbered 31 and labeled “group of Figures” at lower left. Lithograph on laid paper, sheet 17 ½ by 13 inches. In 1926 the American Institute of Graphic Arts selected Group of Figures as one of the Fifty Prints of the Year. Georgia Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. R. Kenneth Sigmund; McKelvey photograph.

Karasz helped found and served on the executive committee of the American Designers’ Gallery, which comprised a veritable who’s who of leading Jazz Age modernists, including Donald Deskey, Wolfgang Hoffmann, and Henry Varnum Poor, and held two major exhibitions of modern American design in 1928 and 1929. Through these well-publicized events, the group sought to “serve as a testing ground for contemporary art,” “work with manufacturers in adapting new materials to decorative uses,” and “[uphold] the principle of the recognition of the designer’s name on manufactured articles.”6 Shortly after the second exhibition, Karasz and her husband began an extended period of travel that included spending about a year in Java in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, where she transformed an old manor house into a modernist space.

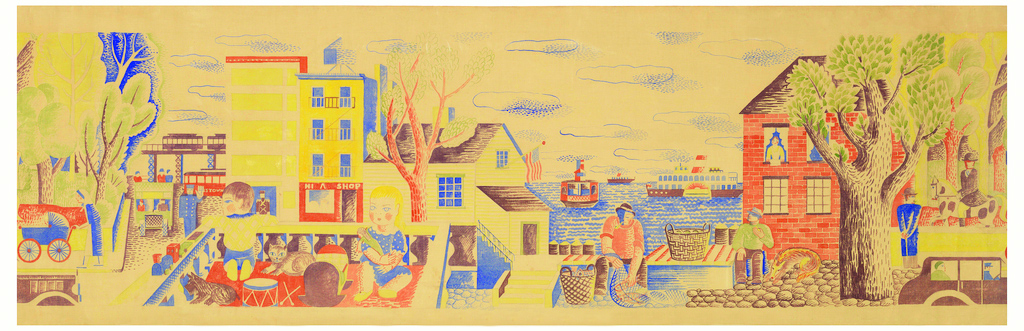

Fig. 13. Frieze by Karasz, c. 1940. Hand painted on drafting cloth, 23 5/8 by 81 inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, gift of Abraham Edelman.

Following the birth of her daughter Carola in 1932 and just before her son Eric was born in 1936, she emphasized nursery design, creating six rooms for Saks Fifth Avenue in New York in the fall of 1935. Critics extensively praised these interiors for their delightful modern designs and for Karasz’s understanding of the practical and psychological needs of the children who would use them. Her sister Mariska, a fashion designer, showed contemporary children’s clothing along with the nurseries.7 In the mid-1930s, Karasz designed for Buffalo Pottery, creating two patterns that were used in the dining cars of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s prestigious Broadway Limited, an express train between New York City and Chicago. Other wares for Buffalo Pottery featured such motifs as symbols of the zodiac, seashells, spoils of the hunt, and animals, all rendered with a beguiling economy of detail (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 12. Textile design by Karasz, 1931. Brush and gouache, graphite, on illustration board, 18 1/8 by 13 7/8 inches. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, gift of Donald Deskey.

Fig. 14a. Drawing for Serenade wallpaper by Karasz, 1948. Graphite, pen, and ink on linen; 12 feet by 3 feet, 4 inches (each). Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Edelman gift.

Fig. 14b. Drawing for Serenade wallpaper by Karasz, 1948. Graphite, pen, and ink on linen; 12 feet by 3 feet, 4 inches (each). Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Edelman gift.

Shortly before World War II, Karasz began focusing on wallpaper design, primarily for the New York firm of Katzenbach and Warren, an activity that lasted into the 1960s. Her earliest papers presented similar compositions to her covers for the New Yorker, while her later papers—which coincided with the postwar housing boom—included experimental printing techniques and Eastern-influenced mural papers that faithfully reflected the detail and charm of her carefully rendered drawings. The recently acquired, and surprisingly large, original drawings for her two-panel Serenade paper (Figs. 14a, 14b) are highlights of the exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt, organized by assistant curator Greg Herringshaw, who is in charge of the wallcoverings department.

Fig. 15. Book illustration by Karasz published in the Modern Art Collector, 1915. Signed “ilonka/karasz” at lower left; printed “book illustration. By ilonka karasz/ © society of modern art./ m. a. c.” at lower center. Private collection.

In 1937 the American Artists Group, which marketed holiday cards during the Great Depression, highlighted Karasz’s success across many fields and explained that she “endow[ed] her expression with all the color and richness of a peasant art tradition, the vitality of a trained designer, and the warmth and originality of an exceptionally creative temperament.”8 William Katzenbach conveyed a similar sentiment in 1947 when he described her wallpapers as having “the primitive qualities of an American sampler, but the sophistication of the New Yorker.”9 During a long and heterogeneous career, Ilonka Karasz consistently presented an elegantly simple style reflecting a unique blend of modernism and folk art.

Ilonka Karasz is on view at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum through April 22.

1 Mariska Karasz, memorandum, August 23 or 25, 1921, collection of Mariska Karasz’s family. 2 Guido Bruno, “Ilonka Karasz, the Hermit Painter,” Bruno’s Weekly, December 25, 1915, p. 317; “The Apotheosis of Greenwich Village,” Vanity Fair, vol. 15, no. 6 (February 1921), p. 37. For more on Ilonka Karasz, see Ashley Callahan, Enchanting Modern: Ilonka Karasz (1896–1981) (Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA, 2003). 3 Foreword, Modern Art Collector, vol. 1, no. 1 (September 1915), n.p. 4 Yearbooks for the Hungarian Royal School of Applied Arts, now the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, are available online at issuu.com/momekonyvtar/docs. Karasz’s name appears on p. 18 of the 1911–1912 yearbook and p. 23 of the 1912–1913 yearbook. 5 “The House in Good Taste,” House Beautiful, July 1928, pp. 45–48; ibid., August 1928, pp. 149–152. 6 “Spain Reflected in Summer Houses,” New York Times Magazine, August 5, 1928, p. 19. 7 For more on Mariska Karasz, see Ashley Callahan, Modern Threads: Fashion and Art by Mariska Karasz (Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA, 2007). 8 Original Etchings, Lithographs, and Woodcuts Published by the American Artists Group, Inc. (American Artists Group, New York, 1937), p. 28. 9 “Blueprinting Used in New Wallpaper,” New York Times, June 20, 1947, p. 16.

ASHLEY CALLAHAN is an independent scholar based in Athens, Georgia, and the former curator of the Henry D. Green Center for the Study of the Decorative Arts at the Georgia Museum of Art. She is currently the guest co-curator of Crafting History: Textiles, Metals and Ceramics at the University of Georgia at the Georgia Museum of Art. She is also the author of several books, including Modern Threads: Fashion and Art by Mariska Karasz; Enchanting Modern: Ilonka Karasz (1896–1981); and Georgia Bellflowers: The Furniture of Henry Eugene Thomas.