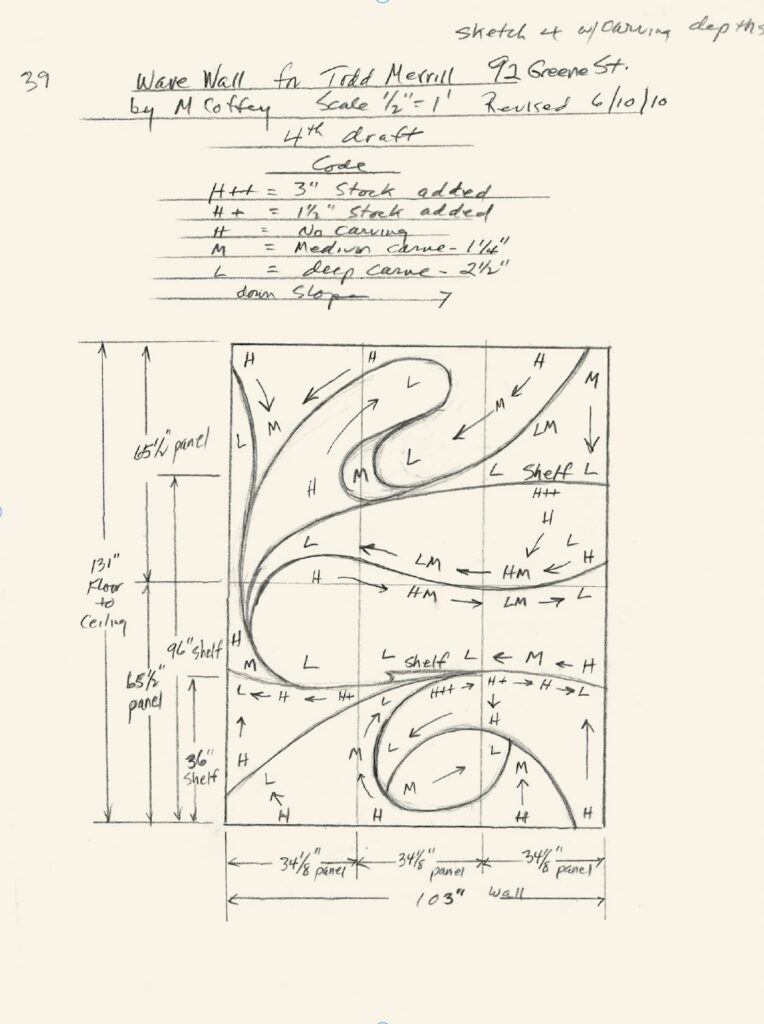

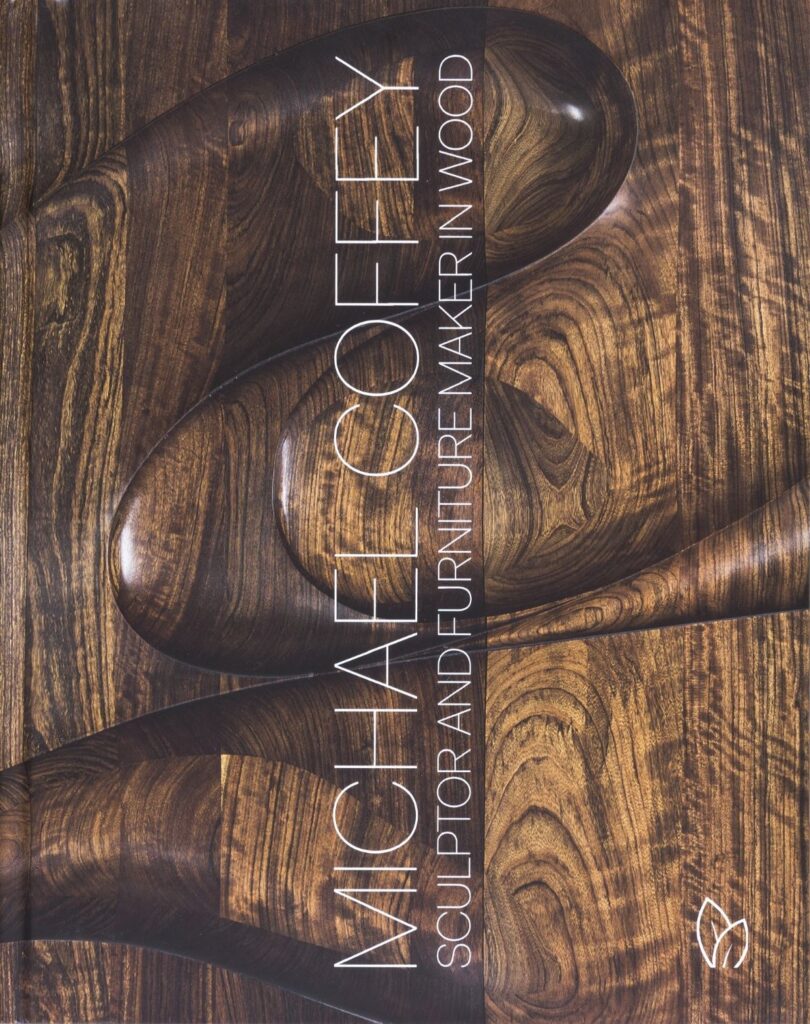

African Mozambique; height 12 feet 7 inches, width 8 feet 7 inches, depth 3 1/2 inches. Except

as noted, the objects illustrated are in private collections; photographs are from the archives of

Michael Coffey. All photographs courtesy of Pointed Leaf Press, New York.

Introduction

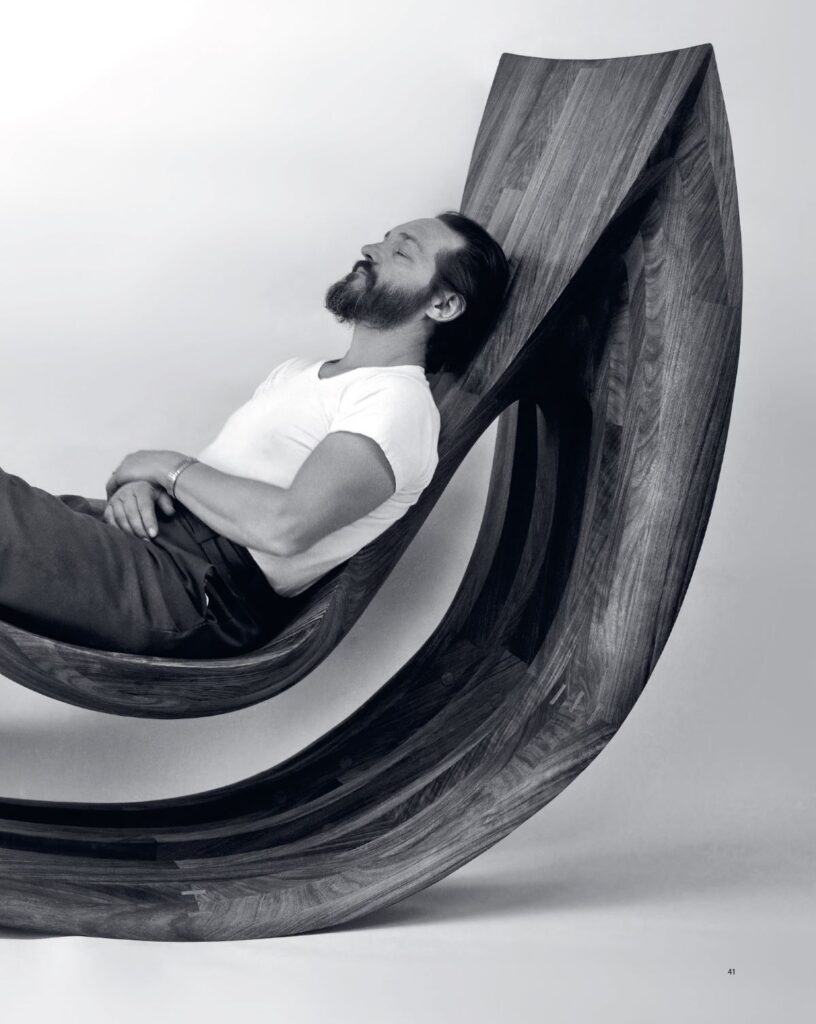

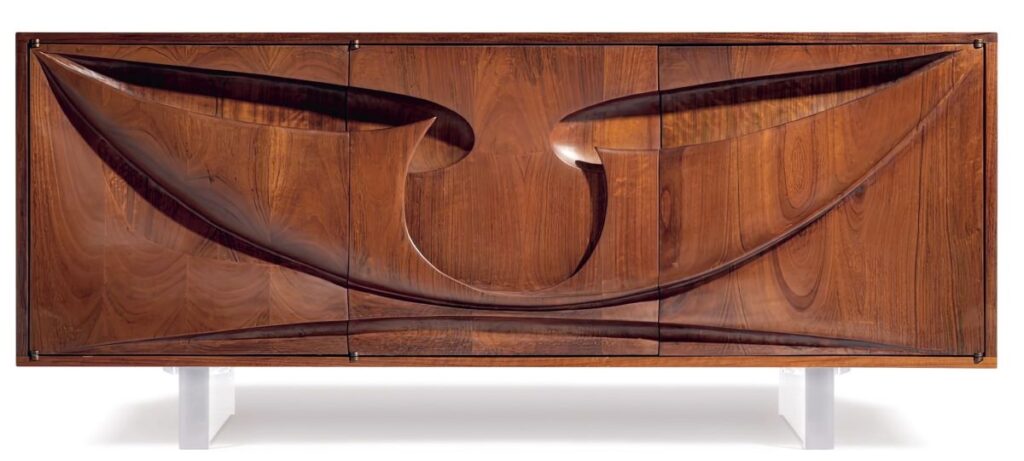

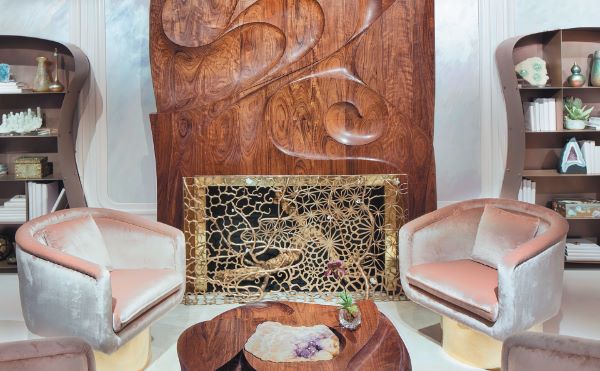

Michael Coffey is a master craftsman and an artist; in his home studio in western Massachusetts, he makes furniture in wood that has the presence of sculpture. To my mind, he belongs in the pantheon of the greats of the American studio furniture movement, alongside Wendell Castle, George Nakashima, Jack Rogers Hopkins, Sam Maloof, and Wharton Esherick—his inspirations. Like them, Michael has created a visual language all his own. Working in woods that range from black walnut to Mozambique, a highly figured African wood, and using the direct-carving technique, Michael makes furniture that has a lyrical quality—curving, asymmetrical lines and forms that flow like water, yet have the power of geological forces. I have admired Michael’s work for decades. I have commissioned pieces from him; I collaborated with him; I have his work in my home. Michael Coffey is a national treasure.

Now ninety-three and still at work, Michael has just published a book—part biography, part artist’s statement of intent. It’s a wonderful read. His life story is fascinating. As a small child, he moved with his parents—his mother was a landscape architect, his father was a writer—from New York City to rural Bucks County, Pennsylvania to escape the worst of the Depression. Eventually they moved back, and Michael enjoyed a progressive education in the schools of Greenwich Village. Imbued with high ideals by his parents and teachers, he earned degrees in social science and began his career as a community organizer in New York, working mainly to improve housing conditions in struggling neighborhoods. While the goal to help others was noble, the work was slow, arduous, and very often frustrating. The chapter from the book that follows describes how Michael began to realize that one of his longtime hobbies—woodworking—might offer a path to a more fulfilling creative career.

I hope you enjoy Michael’s book and the amazing, fascinating story of his life and career. He is a living legend, a wonderful artist, and, more importantly, a wonderful man.

—Amy Lau, interior designer, New York City

Woodworking has been a central avocation in my life since childhood. I always managed to find a shop or at least some simple hand tools to make things out of wood. In the upper grades at my elementary school, the Little Red Schoolhouse in Greenwich Village, woodshop was one of my favorite activities. I made little boxes, and carved totems as gifts. After graduate school, when I worked for settlement houses with woodshops, I spent my off-hours making cabinets and bookshelves for my family or the apartments I lived in. I loved the smell of wood and took pride in the final results, however amateurish. But I never looked upon it as a business, because my energies in those early years were elsewhere. I was on a mission to help other people, not myself. Business meant selling things and making a profit. This use of one’s talent was frowned upon in my family and the progressive, intellectual milieu in which I grew up.

But making things for myself, my friends, or my family was okay. It had no political connotations. It was fun. I learned about tools and techniques from reading books. In my first group- work job in 1955, after getting out of the army, I used the woodshop in Norfolk House in Roxbury, Massachusetts, to make shelving and simple furniture for our apartment. I met Duncan, the husband of my wife’s colleague at work. Duncan and a partner ran a full-time cabinet shop in Boston. His setup really turned me on—the smell of wood, the fancy equipment, the crisp and clever designs he and his partner were turning out. Duncan invited me to craft shows in Massachusetts and New Hampshire, where I saw mind-boggling furniture, gifts, and sculpture made of exotic woods. I was hooked. But only as a hobby, because my primary mission in life was still to “save the world.”

In 1957, my wife, Ellie, and I moved to New York, when I took a job organizing in the Puerto Rican community in the Chelsea neighborhood. I continued woodworking in the shop at the Hudson Guild, the sponsor of the effort. But it was hard to get the hours in because my day job spilled into the evenings when the shop was open for working people. I often ended up working on projects in my apartment in Yonkers. I made a teeny shop in a closet where I had a vise and hung my tools. However, our landlady, who lived on the first floor of the two-family house, became nervous at the sounds of power tools coming from above. So I had to confine my noise and dust to when she was not home. I was becoming increasingly frustrated with the limitations of using other peoples’ facilities, so Ellie and I decided to buy a house where I could have my own shop. Our budget was very low and even with the generosity of our parents, we were able only to afford property at the outer reaches of New York. We finally located a fixer-upper in Staten Island, where real estate values were depressed because the only access to the other boroughs was by ferry.

But I was like a pig in his proverbial milieu. I had oodles of projects to work on to renovate the building, a nondescript, two-story, early twentieth-century frame house. I set up my shop in the basement and began to equip it with hand- and power tools. I tore down walls and built cabinets all over the house. I built decks, put in picture windows, constructed masonry walls, painted the entire house inside and out, and rewired sections of the ancient electricity. My neighbors were impressed. They loaned me tools and gave advice. I read more books on woodworking, carpentry, masonry, and electricity. And every day, I still took the ferry to Manhattan to rescue humanity. It was a pleasant duality. Two passions: One paying the bills and the other, fun. Both conferred a sense of satisfaction and self-worth. But as I moved from one community organization job to another, the futility of really making a difference became more obvious. I still loved working with people, but the zip had gone out of it because I really wasn’t getting anything done. Many people in their careers reach a plateau where they have to acknowledge that their youthful dreams were unrealistic. So they hunker down to boredom and fine-tuning their pay scales, job advancement, and vacations. I was not built that way. I was driven to achieve something in life. This restless ego was not content to settle for mediocrity.

Plus, I did have an alternative that had been stealthily creeping up on me. From the time we bought the house in Staten Island, I began to relate to woodworking as a career. But there were many practical problems. I had no training in that field and, despite the books I had read, my knowledge was spotty. It would take several years to go back to school, because by now I had a family of three children to feed, clothe, and send to school. As a good mother, Ellie could work only sparingly. Starting a new business would take years before it could bring in an income. It’s not like being employed by someone where there is a paycheck waiting at the end of the first week. There were also the practical issues of pricing and cash flow. I knew by that time how long it took to make a piece of quality furniture. I visited many home furnishings showrooms in New York, full of well-made chairs, tables, and cabinets, mass-produced and thus reasonably priced. I knew I could not compete with these goods. To make a living crafting furniture, one piece at a time, I would have to charge three or four times the price. I would starve.

As I searched for a solution to this problem, I realized that there were rebels in the craft world who were making things one piece at a time and apparently earning a living. Their work was not hastily put together or poor in quality. On the contrary, it was at the highest level of design and impeccably crafted. Apparently, their secret was to offer something unique, so different from ordinary furniture that no one could buy it except from these artists. I am talking about such iconoclasts as Wendell Castle, George Nakashima, Jack Rogers Hopkins, and Wharton Esherick. Each had his own distinctive style, so they did not compete with one another. The uniqueness of their work attracted collectors who were seeking something no one else had. They could raise their prices to a level that justified the time invested. Why could I not do the same? Being different would also quench the thirst of my rebellious soul.

My first woodworking hero was George Nakashima, a woodworker/architect in New Hope, Pennsylvania, who elevated the reverence for trees and wood with all its defects to a spiritual level. Nakashima used slabs of wood with their natural edges still intact from the contours of the log for the edges of tables and cabinets. Defects such as knots or splits were embellished and featured rather than removed. From 1967 to 1973, when I was seriously contemplating a career in woodworking, I made several pieces of furniture that used natural-edge boards in the style of Nakashima. Wendell Castle, in Rochester, New York, was charting new territory carving sensuous furniture forms out of solid wood. Castle was probably my most powerful inspiration because he did not take what nature provided him, but created masses of wood in a process called “stack lamination,” and then carved whatever form he wanted. This opened up unlimited possibilities and elevated his work into true art/sculpture.

In California, Jack Rogers Hopkins was blowing through all norms, creating pieces that looked more like sculpture than furniture. Wharton Esherick, the grandaddy of all iconoclasts, was upending all conventions of design, from architectural features to furniture, to door handles, in his studio in Paoli, Pennsylvania. I found these ideas incredibly exciting. They opened up a path to pricing and marketing that bypassed the problem of the long hours it took to make individual, beautiful, high-quality pieces of furniture. But on a deeper level, the work of these artists switched on dim lights that had been buried in my subconscious for thirty-five years. Like smoldering embers smothered by an absence of oxygen, they burst into flame when the windows were thrown open. But the embers were there long before I ever heard of Wendell Castle and George Nakashima. Their glow was embedded in me since childhood, and it drew me to these iconoclastic artists like a moth to a flame.

This article is excerpted and adapted from Michael Coffey: Sculptor and Furniture Maker in Wood, published by Pointed Leaf Press (New York, 2023).