In a defiant opening salvo, in its debut issue of January 1922, The Magazine ANTIQUES declared itself to be, on general principle, opposed to modernity. “These are the days when the mahogany of time-worn experience is being split into kindling wood, or jammed ruthlessly up attic, or sold, with other heirlooms, to the junkman,” bemoaned the magazine’s jocular founding editor, Homer Eaton Keyes (1875–1938), only half in jest.

Rallying to his side all “defenders of the past,” Keyes sketched his plans for the new publication, one he hoped would be both authoritative and free of “twaddle.” Showing objects in interiors was a mission left to rivals. Keyes advocated a sober-minded and scholarly approach to antiques, like that advocated by dealer Israel Sack (1883–1959), who from his pulpit in Boston warned in an ad in the November issue, “Sentiment is a poor guide to the collector who wishes his possessions to constitute a really significant unit, rather than a heterogeneous aggregation.”

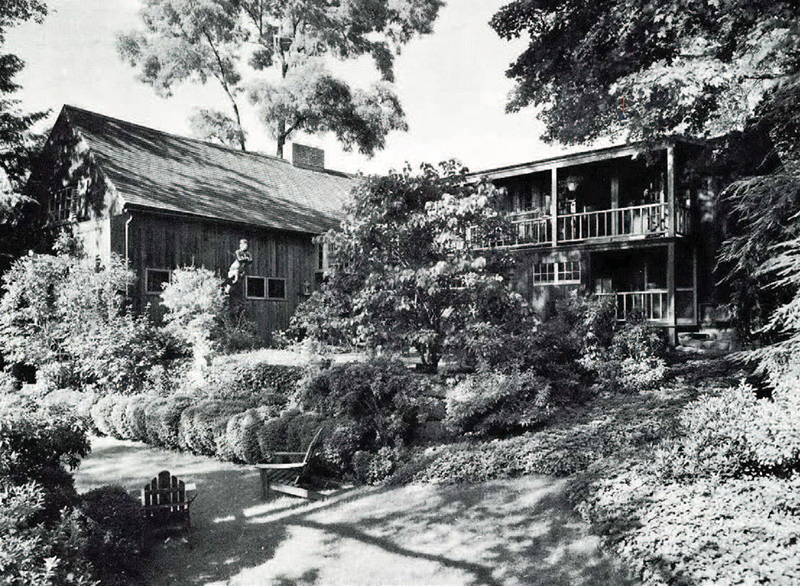

Fig. 3. Alice Winchester (1907–1996) introduced the 1950 Milwaukee home and collection of Stanley (1896–1987) and Polly Mariner Stone (1898–1995) in May 1956, and ANTIQUES revisited it in May 1986. See also Fig 7. Rocheleau photograph.

Keyes’s disdain for “sentimental vaporing,” as he put it in 1927, remained so pronounced that, on the occasion of the magazine’s twentieth anniversary in January 1942, journalist Charles Messer Stow (1880–1952) avowed, “I have a strong admiration for The Magazine ANTIQUES because it never introduced a ‘department of decoration.’” Having thus forsworn frivolity, ANTIQUES came hesitantly to its ever-popular “Living with Antiques,” officially introduced to these pages in July 1943 (Fig. 12). In the decades since, the magazine has shown the interiors of dozens of private homes, arranged by the self-same “defenders of the past” who answered Keyes’s call for community.

“Living with Antiques” and its precursors—most notably “Antiques in Domestic Settings,” a series launched by the magazine in October 1935—survive seriatim as an engrossingly varied if often oblique tribute to the collectors, curators, dealers, decorators, writers, editors, photographers, and designers who together created the forum that Keyes rather floridly described as “the real place of rapture for all true zealots.” What we collect, how we live, what we feel comfortable sharing with strangers—all that has changed. What is much the same is our belief in the power of historically resonant objects to inform and delight, to speak to us in deeply personal ways, to light our inner sanctums. As Keyes’s successor as editor, Alice Winchester (1907–1996), wrote in 1963, “living with antiques does not mean living in the past: it means preserving and enjoying the best of the past in order to add an extra dimension to the present.”1

How Not To Live with Antiques

The accumulations ANTIQUES did much to inspire presented readers with a conundrum: how to display their unwieldy agglomerations. In July 1935, the magazine turned to Ruth Webb Lee (1894–1958), a much-published authority on early American glass, whose story “Collections in the Home” offered a taste of the magazine’s advice-dispensing articles to come. In her somewhat clinical approach, Webb acknowledged ruefully, “The task of reconciling scientific arrangement with tasteful and attractive display is no easy one.”

ANTIQUES consulted interior decorators sparingly, and then only if they demonstrated substantial historical knowledge. A prominent designer known for books on topics ranging from historic wallpaper to Duncan Phyfe, Nancy V. McClelland (1877–1959) supplied the January 1942 article “Decorating with Antiques,” which pointedly linked the rise of interior decoration as a profession to the emergence of antiques collecting in the United States. Decades later, ANTIQUES spoofed itself with its playful January/February 2015 feature “Living with Thomas Jayne,” an homage to a decorator known as a foremost interpreter of historic American design.

The Great Awakening

Editor between 1938 and 1972, Alice Winchester did much to widen interest in antiques among America’s middle classes, a campaign expanded by her successors, Wendell D. Garrett (1929–2012), an unsurpassed brand ambassador for the magazine, and his protégée, Allison Eckardt Ledes (1954–2008). Winchester did so chiefly by way of lecturing, book publishing, and through her collaboration with Colonial Williamsburg on its Antiques Forum, which the magazine helped launch in 1949. A compilation of interiors first published in the magazine, Living with Antiques appeared in book form in 1941, two years before Winchester adopted the name for the feature stories. The book’s success prompted its reissue with updated content in 1963. As Winchester years later explained, “It seemed to me a logical approach and a way to get people interested in more things, different kinds of things.”2

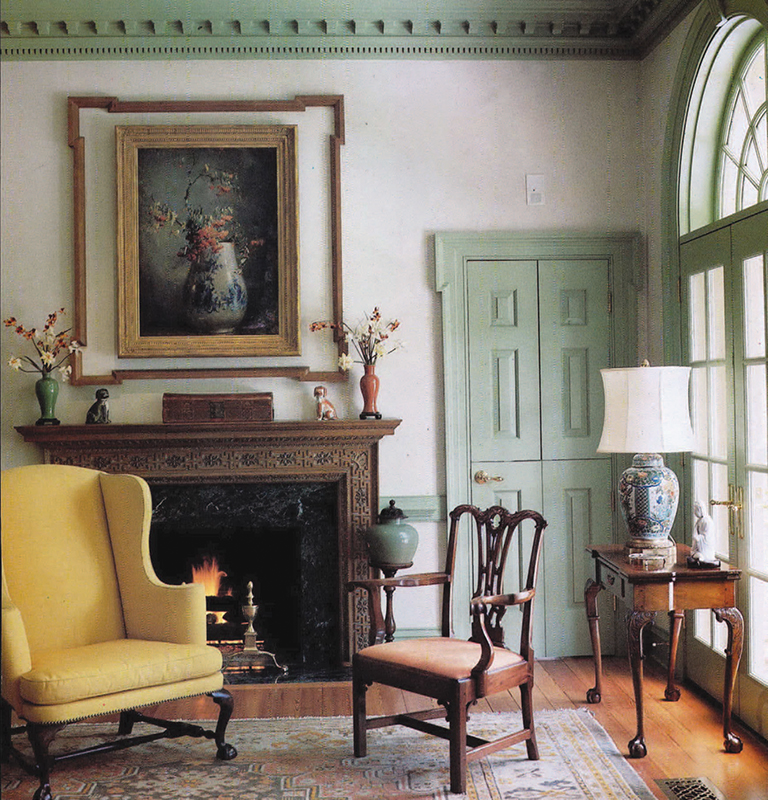

In his foreword to the 1941 edition, Joseph Downs (1895–1954), curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s American Wing, hinted at the pitfalls for collectors seeking to emulate the “period room,” so popular at the time with visitors to his institution and others like it. “Period rooms are educational but seldom real. They are important for education, to show the evolution of period styles and sequences of design elements. They are dramatic but overemphasized— in short, they are propaganda, used as the writer of a war novel concentrates the personal experiences of many people in one individual,” wrote Downs, whose own early eighteenth-century house in Connecticut was the subject of one of the magazine’s first “Living with Antiques” features, in October 1943.

The curator’s warning that antiques be used “not as museum pieces in a make-believe world” fell on deaf ears. Playing house was a favorite pastime for mid-century collectors of means, from Katharine Prentis Murphy (1882–1967), whose white clapboard residence in Connecticut the magazine featured in June 1950, to Ralph E. Carpenter Jr. (1909–2009), whose new old house, Mowbra Hall, concocted in part from architectural salvage, appeared in consecutive issues of ANTIQUES in May and June 1952.

Good, Better, Best

Winchester’s other great contribution was her encouragement of promising contributors, among them Israel Sack’s son, dealer Albert Sack (1915–2011). As Sack later told me, the idea for his best-selling book of 1950, Fine Points of Furniture: Early American, stemmed from a lunch he had two years earlier with Winchester, during which she asked him to write “Good, Better, Best: In American Eighteenth-Century Furniture,” published by ANTIQUES in December 1948.3

Sack’s genius was to distill the complexities of connoisseurship into an easily understood system for ranking furniture. The brilliance of his firm, Israel Sack, Inc., and that of its rival, Ginsburg and Levy, subsequently Bernard and S. Dean Levy, was the authoritative guidance they provided to the foremost collectors of American decorative arts. The dealers’ legacies live prominently in the collections of George and Linda Kaufman, promised to the National Gallery of Art and featured in ANT IQ UES’ ninetieth anniversary issue May/June 2012 (Fig. 15) and that of Joseph and June Hennage, published in ANTIQUES in December 1990 and formally presented to Colonial Williamsburg in 2021 (Fig. 9).

The magazine occasionally followed the evolution of a house and its furnishings over many decades. In February 1938, Keyes rhapsodized about The Lindens, erected by Robert “King” Hooper in Danvers, Massachusetts, in 1754 and moved to Washington, DC, by Mr. and Mrs. George Maurice Morris. The magazine returned to the subject twice more, in 1956 and 1979. Likewise, in May 1956 Winchester wrote about the evolving interests of Mr. and Mrs. Stanley Stone of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, describing their initial visit to Israel Sack, Inc., in New York in search of a desk (Fig. 3). ANTIQUES chronicled the culmination of the couple’s pursuit in a piece by curator Oswaldo Rodriguez Roque, published in May 1988, shortly after Chipstone began its transition from private home to influential foundation (Fig. 7).

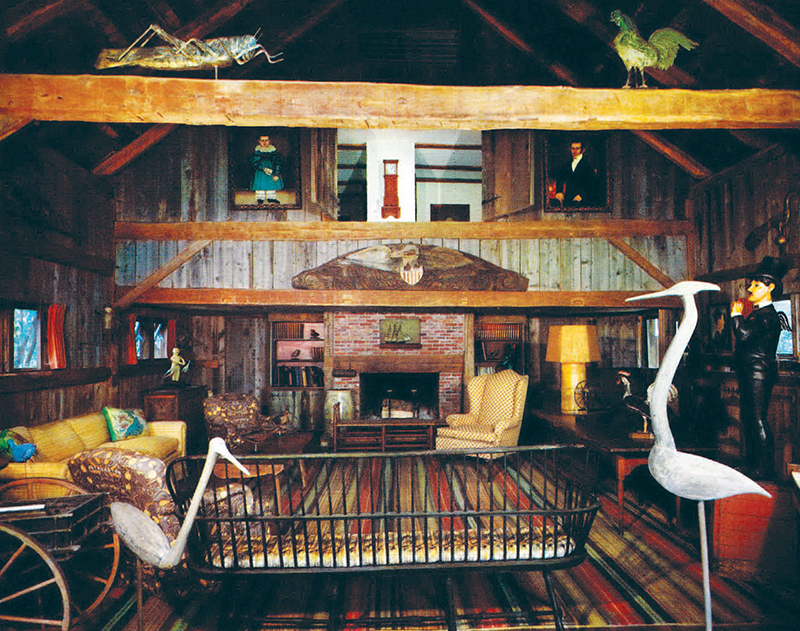

Even as Albert Sack helped codify rules for collecting, others were steadily breaking them. In June 1957 ANTIQUES published the home of editor and author Jean Lipman and her husband, Howard. The Connecticut enthusiasts had already formed a major collection of American primitive painting, transferred to the New York State Historical Association in Cooperstown, New York, in 1950. The 1957 feature that followed illustrated the Lipmans’ growing affinity for boldly painted American country furniture and folk sculpture, two collecting categories they helped popularize.

Antiques in the Heartland

Heralding the geographically focused scholarship to come, Winchester in January 1943 penned “Collecting Regional Americana.” Pennsylvania and the South merited special attention. Pennsylvania German decorative arts came into clear focus in 1947 with features in April and October, respectively, on the collections of Asher J. Odenwelder Jr. and Titus C. Geesey. Other landmark assemblages of Pennsylvania decorative arts and folk art have included the New York City apartment of Ralph Esmerian, an American Folk Art Museum benefactor, in September 1982 (Fig. 13), and the Philadelphia-area homes of two prominent collecting couples, both unidentified at the time: Joan and Victor Johnson (September 1988) and Leslie Anne Miller and Richard Worley (January 2010). The gifts of Geesey, the Johnsons, and Miller and Worley today enrich the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

ANTIQUES’ interest in the South is deep and sustained. In August 1931, the magazine published “Simple Furniture of the Old South,” Mary Ralls Dockstader’s lively account of Thomas Keesey’s rambles through the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, where the Indiana businessman “picked” vernacular furniture “here and there, mostly from country dealers, without,” Dockstader wrote, “any undue outlay of time or effort.” The antebellum mansions of Natchez, Mississippi, have been a perennial favorite in the magazine since ANTIQUES first showed them in March 1942.

Reflecting recent trends in scholarship and collecting, ANTIQUES in 2010 and 2011 turned its eye to the southern backcountry with “Living with Antiques” features by Sumpter Priddy III, who wrote about Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and southern Piedmont artifacts collected by Roddy and Sally Moore, and by MESDA curator Daniel Kurt Ackermann, who surveyed the Kentucky collection of Sharon and Mack Cox.

Revisionist Histories

“Anyone who saw the great Girl Scouts loan exhibition of 1929 or who has pored over its catalogue—as what collector of American antiques has not?—remembers that one of the significant collections represented was that of Mr. and Mrs. Andrew Varick Stout,” Winchester wrote in the magazine in May 1961. In June 1936 ANTIQUES had published the Stouts’ elegant New York City dining room—complete with Federal chairs, window bench, and side table described as from the shop of Duncan Phyfe—but it was not until the 1960s, partly through the influence of curator Berry B. Tracy (1933–1984), that classical American fine and decorative arts became an important collecting specialty.

Institutional and private collectors from there pushed forward into the second half of the nineteenth century, often seeking to recover the history of reform movement design on both sides of the Atlantic. Writing in ANTIQUES in June 1995 about a foremost holding of English Gothic revival decorative arts in a private collection, Martin Levy, director of the London antiquary H. Blairman and Sons, observed, “It has taken the best part of the twentieth century for the decorative arts of the Victorian era to emerge fully from an extended period of cultural eclipse” (Fig. 14)

Modernist art and design were not part of ANTIQUES’ original remit. Keyes nevertheless spied a parallel sensibility in the clean lines of Biedermeier furniture, glimpsed in the home of Arthur M. Allen in the March 1930 issue, and in Shaker furniture, as illustrated in October 1936 and again in January 1939 in the Massachusetts residence of scholars and ANTIQUES contributors Edward Deming Andrews (1894–1964) and his wife, Faith (1896–1990). Modernism acquired patina with the millennium’s turn. ANTIQUES signaled its approval with its July 2001 feature on the fertile collaboration of client Richard H. Mandel, architect Edward Durell Stone, and designer Donald Deskey on a 1933–1935 country house in the international style in Bedford, New York (Figs. 2, 17). The magazine moved further afield in May/June 2013, presenting an important assemblage of early modernist American paintings and sculpture in the Manhattan apartment of Jan and Marica Vilcek, émigré collectors from eastern Europe who, startlingly, paired the works with Viennese Secessionist design (Fig. 19).

Really Living with Antiques

For most of its history, decorum—or was it excessive deference?—prevented ANTIQUES from revealing much at all about the individuals who formed the collections shown on its pages. Who were these acquisitors? Why did they do it? How did it make them feel? If scholarly remove elevated an object, then biographical detail about its owner cheapened it, or so the thinking seemed to go. A similar detachment characterized concurrent museum publications, which—coinciding with growing interest in the history of collecting—have increasingly included detailed notes on provenance.

Some of ANTIQUES’ most revealing features have been by collectors themselves. One thinks of Nina Fletcher Little (1903–1993), the indefatigable scholar, collector, and ANTIQUES contributor who, in June 1940, wrote about “rehabilitating” her early eighteenth-century Massachusetts farmhouse, Cogswell’s Grant. Or the colorful dealer and advisor J. A. Lloyd Hyde (1902–1981), who described his stylish Connecticut house, Duck Creek, in these pages in December 1957. He returned in August 1963 with a report on his Newport, Rhode Island, residence, Pagoda House, which he purchased in 1956, just as the city’s preservation effort was gathering steam.

Conventions fell when Elizabeth Pochoda took the editor’s chair in 2008. With an appreciation for language and a keen sense of the broader cultural zeitgeist, Pochoda updated “Living with Antiques” in important ways, often dispensing with the title itself, occasionally showing the collectors in their homes, and, in at least one instance, including framed family photographs, considered “too much information” in magazine land. In her September/October 2012 story on New Orleans’s 1835 Grigson-Didier house and its owner, Don Didier (1944–2019), Pochoda asserted contrarily, “This is not a collector’s house, and his is not an especially acquisitive nature.” Shown against a backdrop of cracked plaster and smudged paint in the hyper-realistic fashion promoted by The World of Interiors, a fashionable London glossy, the Didier trove was subjective in meaning. The house itself, Pochoda wrote, “has become one American’s dialogue with America—North and South, past and present, black and white.”

New Social Order

Editor Gregory Cerio’s July/August 2019 feature “Bent Pennies” represents a contemporary approach to living with objects, not strictly antique, in which boundaries are fluid and rules are few (Fig. 21). The orderly proportions of a shingled house in Sag Harbor, New York, hint at the eighteenth century, but inside the presentation is clean and bright, aligned with our current distaste for clutter. There is no suggestion of period rooms in these ahistorical arrangements: the highly sculptural silhouettes of antique Windsor furniture and nineteenth-century folk carvings serve as counterpoint to the graphic exclamations of William Hawkins, Martin Ramirez, and other self-taught and outsider artists of the twentieth century. Breadth of interest, rather than a specialist’s focus, characterized the late collector, Larry Dumont, a child psychiatrist whom Cerio described as “sensitive to the wrinkles in the fabric of the human condition.”

That ANTIQUES would evolve, Keyes and his successors were certain. As the founding editor wrote—somewhat cryptically, we might add—in his opening editorial, like the program of an amateur variety show, the magazine “is subject to change, without notice—and without doubt.”

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author thanks Elizabeth Stillinger, who as a fledgling journalist assisted Alice Winchester with the 1963 edition of Living with Antiques, for sharing her unsurpassed knowledge of collectors and collecting. Thanks also to Gregory Cerio, Eleanor Gustafson, and Elizabeth Pochoda for their insights and suggestions.

1 Alice Winchester, “Living with antiques” in Living with Antiques: A Treasury of Private Homes in America, ed. Alice Winchester and the staff of ANTIQUES (New York: E. P. Dutton, 1963), p. 9. 2 Oral history interview with Alice Winchester, September 17, 1993–June 29, 1995, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. 3 Author’s interview with Albert Sack, Durham, North Carolina, June 9, 2007.