In the early 1980s, the poet Jonathan Williams, a native of North Carolina, invited photographers Guy Mendes and Roger Manley to join him in touring the backroads of the southeastern United States “to document what tickled us, what moved us, and what (sometimes) appalled us,” as Williams later wrote. Their resulting encounters included many with self-taught artists such as Howard Finster, Mose Tolliver, Thornton Dial, Mary T. Smith, and dozens of others, who each, as Williams put it, “make up beauty out of the air, and out of nowhere.”

Williams intended to use Mendes and Manley’s photographs to illustrate the poetic, often humorous reflections that he had compiled into “a true Wonder Book, a guide for a certain kind of imagination.” He titled it Walks to the Paradise Garden, to honor Finster and the Edenic art environment he created, as well as the many other artists who were, Williams wrote, “directly involved with making paradise for themselves.”

In March, eleven years after his death, Williams’s book will finally be published, by Institute 193, a nonprofit in Lexington, Kentucky, dedicated to southern art and culture. The book has inspired an exhibition at the High Museum of Art: Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads, brings together Mendes’s and Manley’s enthralling photographs, works by the artists they profiled from the High’s permanent collection, and excerpts from Walks to the Paradise Garden. The exhibition takes its name from a title Mendes preferred for the book, “Way Out People Way Out There,” which alludes to both the highly original mindsets of the artists featured as well as their geographical distance from conventional art world capitals.

Mendes and Manley are among the many photographers who have turned their lenses toward self-taught artists over the past century. This pattern of attraction can be attributed to many factors, including an underlying kinship between self-taught artists and photographers—both among the types of artists often rejected by the mainstream art establishment. While self-taught artists by definition lack academic training credentials, photographers have also been stigmatized as “mere technicians” rather than true artists.

Throughout his book, Williams disregards the kinds of stigmas and hierarchies that might elevate one artist over another based on factors like training, medium, or place of origin. To Williams, who lived part-time in Europe and knew well the canonical masterpieces of art from around the world, the American South had no shortage of artistic brilliance. As he put it, “Better to go to Greenwood [Mississippi] than Prague.”

Here is a selection of photographs and artworks from the exhibition:

In 1950 Eddie Owens Martin moved from New York City back to his home state of Georgia, taking on the persona of St. EOM (his initials) and dedicating the rest of his life to creating Pasaquan, a world where the wisdom of ancient civilizations fused with his utopian ideas about the future. Jonathan Williams described the epiphanic moment of driving through rural south Georgia and coming upon Pasaquan: “There, just like in The Wizard of Oz, suddenly everything turns Technicolor . . . . No longer are you in the desolate pine woods between the big Ocmulgee and Chattahoochee river valleys. No longer are you next to the paratroopers of Fort Benning. You are not drowning in kudzu, protestant totalitarianism, whorehouses, the drumming of Bible-whackers. You are at the entrance of the finest art environment in the Southeast.”

Williams noted the artistic community that flourished through Thornton Dial’s bloodline, comparing Bessemer, Alabama’s concentration of artistic talent to precedents in Europe: “All this is as mysterious as the fact that the industrial town of Nancy in eastern France produced three great Art Nouveau masters at the same time, Émile Gallé, Auguste Daum, and Hector Guimard …. It will be awhile before the nation realizes what’s cooking in the dark satanic/angelic furnaces of Bessemer, Alabama.”

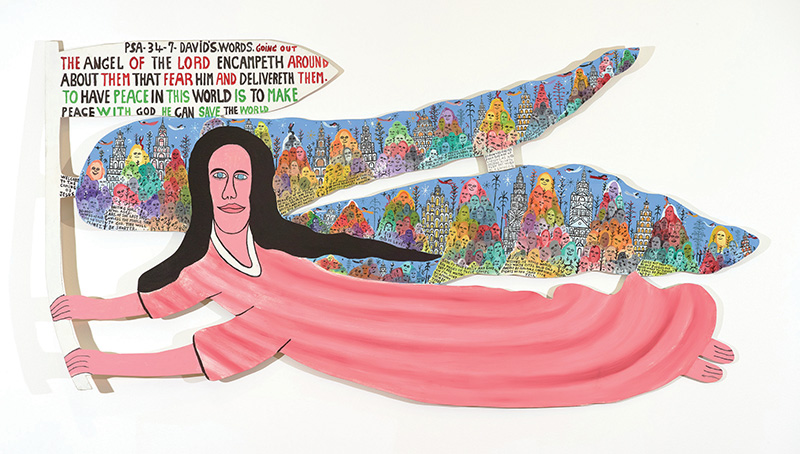

Sister Gertrude Morgan rented a house in New Orleans that she called the Everlasting Gospel Revelation Mission, and this is where she started making art. Mendes grew up in New Orleans and remembered his many visits with Morgan fondly: “Dressed in her white cap, frilly white dress, white stockings and shoes, she comes into the small room. She is playing a tambourine, singing; talking in measure. She sings loudly, through a homemade megaphone—her PA system requires no electricity. Sister Gertrude is on the air, announcing the departure of that Clean Train, telling people to get on board. Sister Gertrude is in the control tower, talking to the man upstairs, who is gliding around in a noiseless, lumpy sort of DC–6 that has no roof . . . . Jesus is steering with one hand, waving with the other . . . . Sister Gertrude is the stewardess, counseling and instructing the passengers en route. In the pouches on the backs of the seats are paintings by Sister Gertrude.”

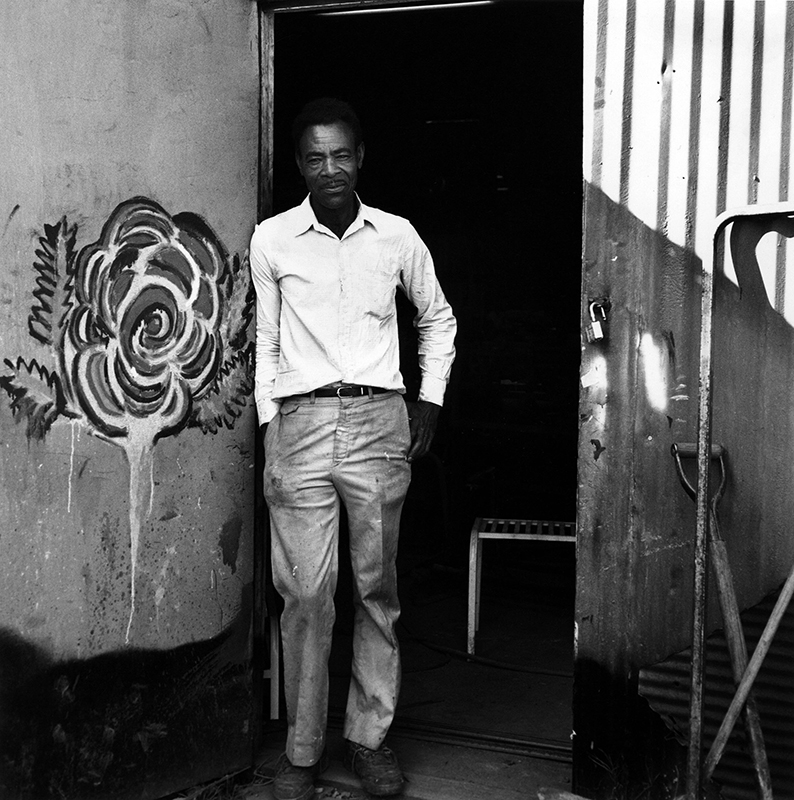

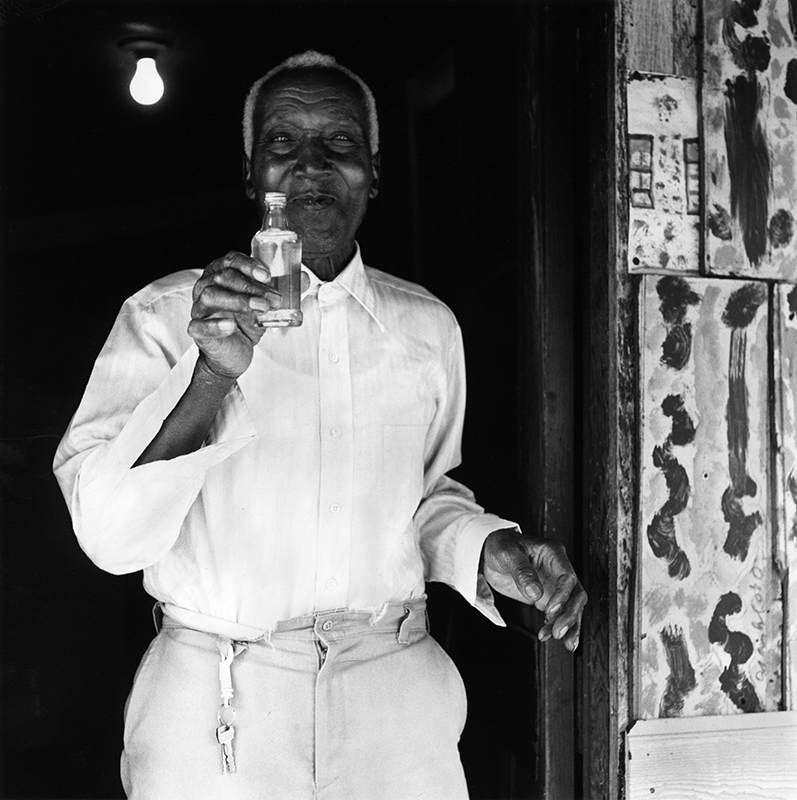

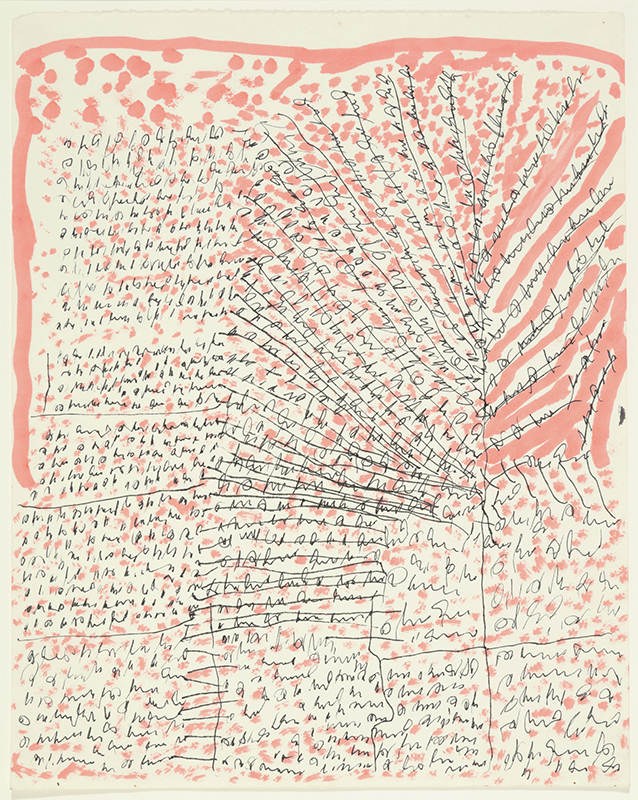

John Bunion (J. B.) Murray was visited by Williams and Manley in 1985 at his home in Sandersville, Georgia. Murray was known for his divinatory writing inspired by the Afro-Atlantic world. Williams wrote that Murray was “producing some 1500 drawings and examples of ‘spirit script’ in his later years. By dint of reading his messages through a vial of sacred water from his well, angels and select holy persons could decipher his beautiful texts. Us witches and devils couldn’t.”

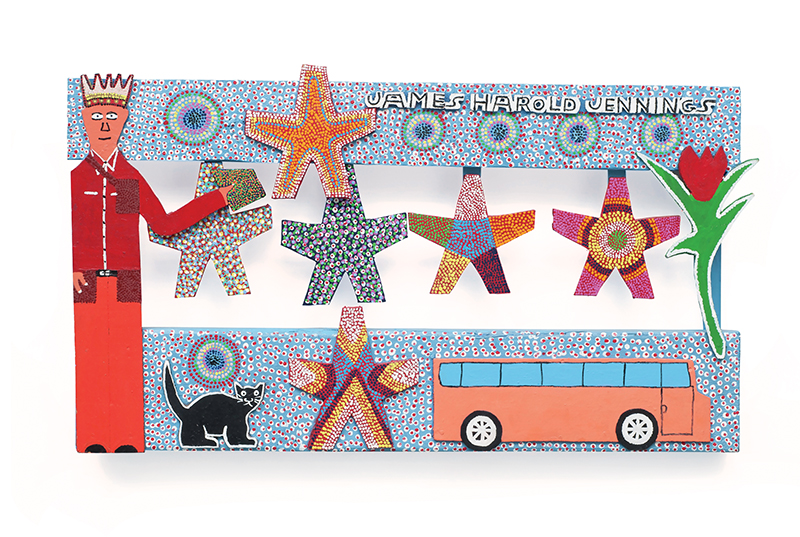

Even though James Harold Jennings’s art environment was a bit off the beaten track, he told Williams: “Well, boys, you know there’s a whole lot of company in what I do. I never ever get lonely . . . . That’s because my art is somethin’ they call visionary art.” In this self-portrait in wood, Jennings depicts himself wearing a stocked tool belt that allowed him to perpetually tinker with his creations as well as his signature painted crown.

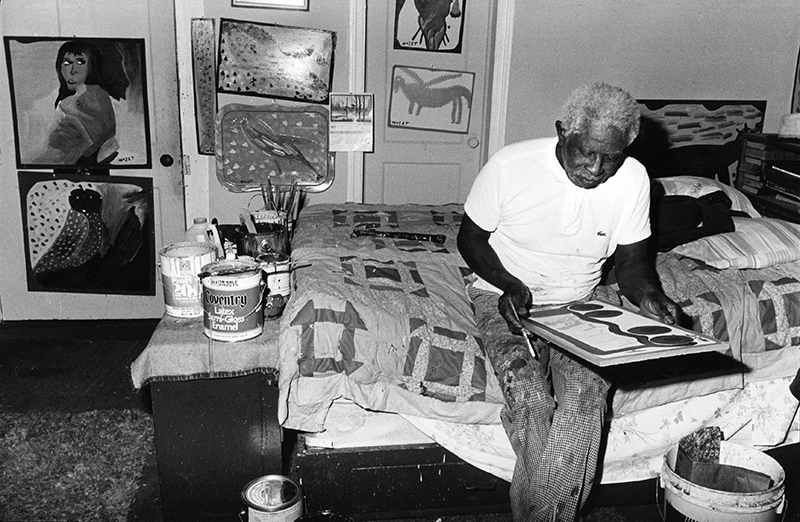

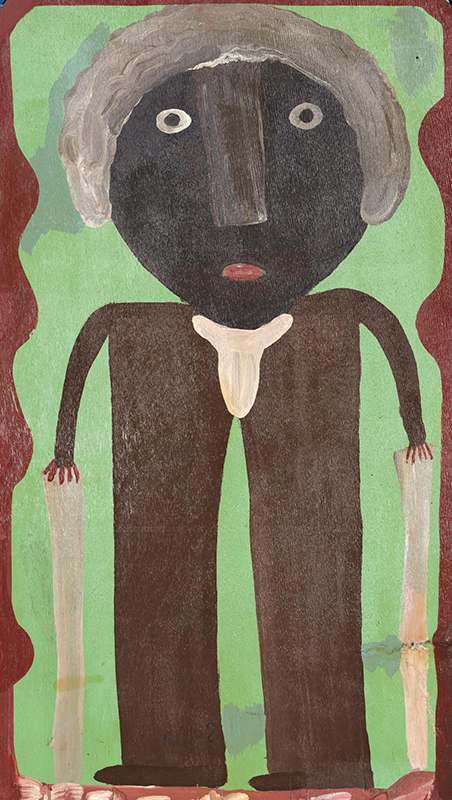

When Williams stopped in Montgomery, Alabama, to visit Mose Tolliver, he was taken with the amount of artwork Tolliver was producing on a daily basis. He wrote: “But, his house was full of paintings. He paints on everything, with anything. Maybe ten a day! A lot of his customers ask him to do this and to do that. He does, but not happily.”

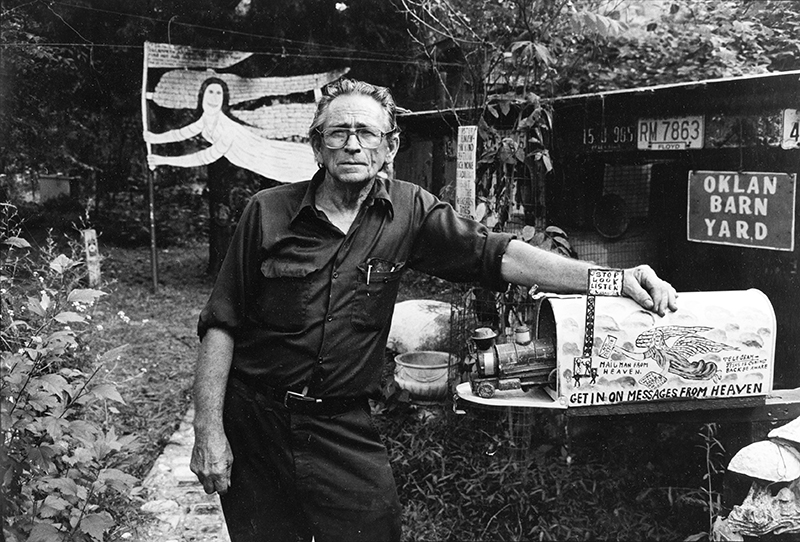

Howard Finster was not your average Baptist preacher. Williams wrote of Finster fondly saying: “Howard, I don’t know the name of the planet you came from. But, when you go back, I sure hope it offers Classic Coke, red-eye gravy, and okra fried just right by the Duck Woman of Orpliss [a curious character that Finster painted]. You deserve the best!” Paradise Garden was a beloved stop for Williams, and he had his own nickname for this site, writing: “I persist in calling it the New Improved Garden of Eden, just to be ornery.”

Way Out There: The Art of Southern Backroads is on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta from March 2 to May 19.

Gregory Harris is associate curator of photography at the High Museum of Art. Katherine Jentleson is the High Museum of Art’s Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-taught Art.