French architect-designer Hector Guimard’s sensuous and organic forms—as seen in cast iron in his most famous works, the Paris Métro entryways—also appear in his buildings, interiors, decorative arts, and design objects in a variety of mediums. Commissioned for the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle, Guimard’s Métro designs, like his other creations, aimed to show the world a new style—art nouveau—which he promoted as “le style Guimard.” While many of his designs certainly bespeak the opulence for which art nouveau is celebrated, Guimard is also to be recognized for his large-scale production designs, in areas such as lighting, and in mass housing. Guimard’s legacy endures thanks in great part to the tireless efforts to preserve his work and memory made by his American-born wife, Adeline. Those efforts formed just one aspect of her multivalent relationship with Guimard, which saw her as not only his spouse, but also as his patron, his muse, his fellow artist, his business partner, and, ultimately, guardian of his posterity.

The parsing of the complex relationship between Monsieur and Madame Hector Guimard is but one element in a reappraisal of the architect-designer’s work and life that is the subject of a newly published book from Yale University Press, Hector Guimard: Art Nouveau to Modernism. A related exhibition, co-organized by the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York and the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in Chicago, is planned; show dates will be announced later this year.

Adeline Oppenheim Guimard was the daughter of financier Edouard L. Oppenheim (1841–1911), who had immigrated from Belgium to the United States in 1857. From childhood Adeline had traveled to Paris with her family and so was at ease when she moved to the city in the 1890s to become an artist, studying painting with Henri-Léopold Lévy (1840– 1904) and other artists.1 Her seriousness about art is clear from her first showing in 1899 of an oil, Mauresque, at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris. A porcelain plate she painted in the manner of Rubens and signed “A. Oppenheim”—bequeathed by her sister to the Cooper Hewitt—gives an idea of her artistry, one without a trace of the le style Guimard (Fig. 12).2

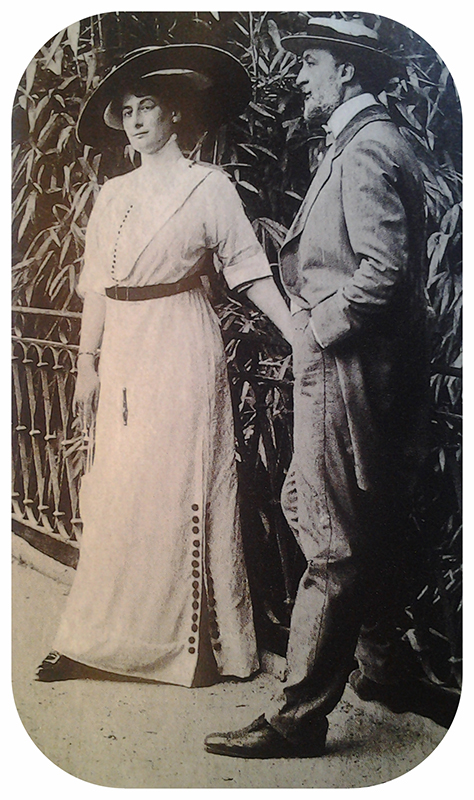

It is unclear how Adeline and Hector Guimard first met, though he was already a well-known architect and designer when they did. Edgar David, a jeweler and antiques dealer on the rue de la Paix whom both knew and who was one of three witnesses at their small wedding, seems their most likely connection.3 What is clear is that the union came about soon after Hector received a substantial sum of money from Adeline’s father, who, along with his daughter, appears to have considered the gift an investment, making his daughter Hector’s partner, and himself a backer.4 The couple’s engagement was short—just a month long. Adeline converted from Judaism to Catholicism, and their wedding on February 17, 1909, took place in the Church of Saint- Francis-de-Sales. Abbé Bellanger, who married them, was not the parish priest, but rather a friend of Hector’s. In his wedding sermon the abbé said of Hector, “you are the art nouveau,” expounding on the designs for Adeline’s engagement ring and the lace of her wedding dress—all of which suggests that the pre-wedding preparations might have focused less on religious instruction and more on style.5 Hector Guimard was almost forty-three years old at the time of the marriage, and Adeline was thirty-six (Fig. 4).

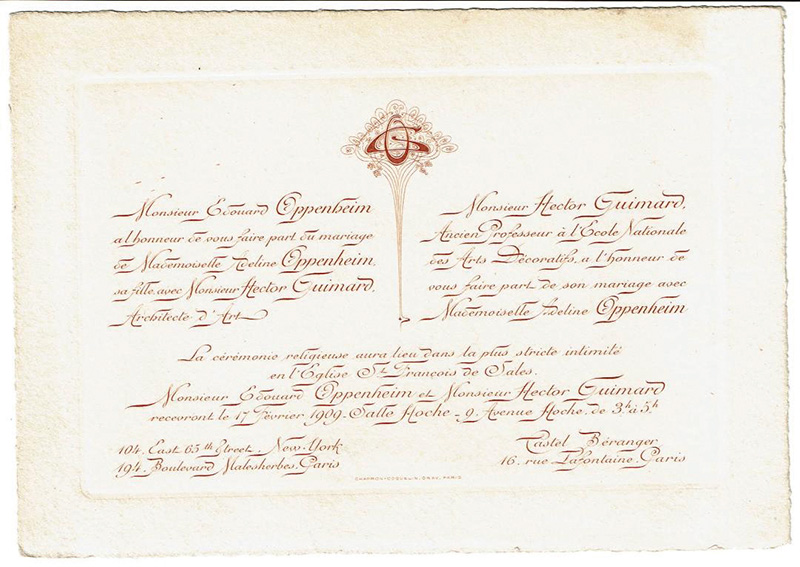

Their subsequent artistic and financial involvements show that the Guimards’ lives became as entwined as the G and O monogram—for Guimard and Oppenheim—designed by Hector for their wedding invitation and their table napkins (Figs. 5, 9). Attention to details like the monogram reflects Hector Guimard’s holistic approach to design— that he create complete environments, each design element a part of a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total artwork. While Adeline may or may not have been a muse for Hector’s designs for her, her presence provided the opportunity for him to design new types of personal objects. He designed her accessories, items of her clothing, and frames for her artworks. Along with her engagement ring, he designed other jewelry for her—including a brooch, hatpin, lorgnette, and pendant (Figs. 14, 19)—that was effectively a wearable promotion of le Style Guimard. The sinuous curvilinear forms of the jewelry complimented the owner, while complementing Guimard-designed furnishings and architecture of the rooms surrounding her. Adeline showed her own inclination to live as a work of art within one in a statement she made at the pre-wedding meeting with Bellanger: “We must make of our life a work of art.”6

Soon after their wedding, the Guimards set out to create such exemplary environments. Within three months, they purchased a building site and began construction of the Hôtel Guimard. The structure was completed in 1910 (Fig. 6)—Hector proudly incised his signature into an exterior wall— and when the interior architecture and furnishings were finished in 1913, the place became as much a showroom for le style Guimard as a home. Hector designed an artist’s studio with northern light for Adeline on the top floor, and her aesthetic became integral to the house’s entire ambience. In the Hôtel Guimard, Adeline found a setting for her paintings, drawings, and collected objects set within the envelope of Hector’s architecture and decor. Her touches personalized the Hôtel Guimard.

The Guimards’ careful arrangements of art and design can be seen in photographs of the interiors of the Hôtel Guimard probably taken around 1913 (Figs. 11, 15, 16).7 (Adeline later gave the photos to the Cooper Hewitt—an invaluable resource as the only known period images of Guimard interiors.) The photos show numerous examples of Hector’s lighting designs, chiefly his lustres lumières chandeliers (Fig. 18). Wired for electricity, they show that the Guimards did not shy away from new technologies in an elegant setting. These designs were published in a catalogue and produced commercially for purchase by a broad audience, much as Guimard did later with his designs for cast-iron balconies and other architectural elements.8

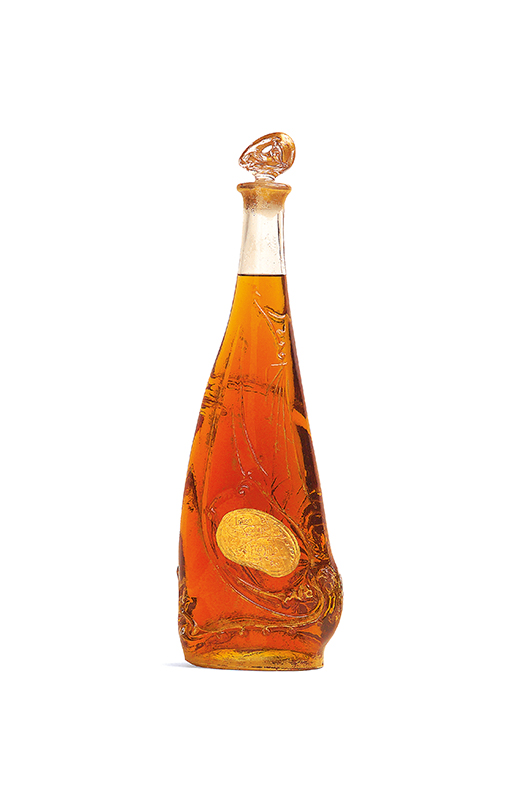

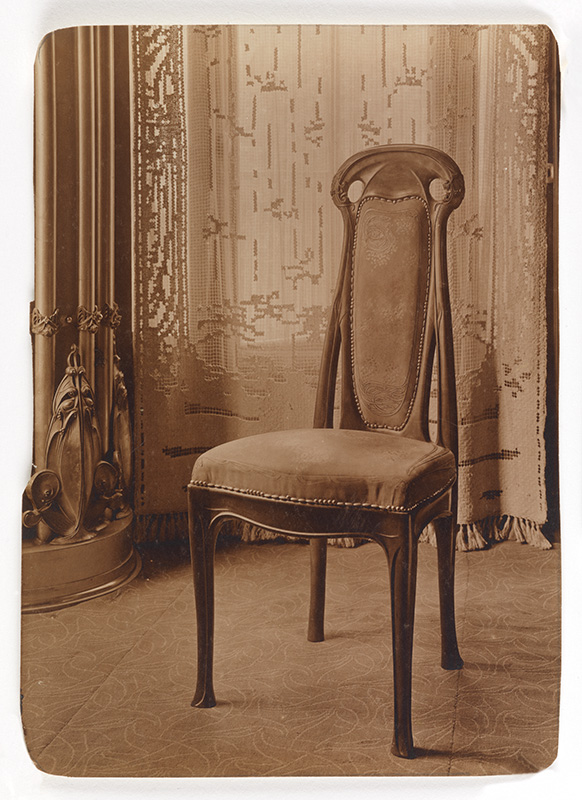

A photo detail of the dining room shows a chair next to lace curtains that look quite like the lace panel of Adeline’s wedding dress (Figs. 10, 15). The room’s metalwork resembles the Métro designs, and the flowing patterns in the upholstery fabrics are reminiscent of the form and label of a bottle Hector designed for parfumier Félix Millot’s Kantirix Lotion, intended for display at the Paris Exposition of 1900 (Fig. 2).9 A photo of Adeline’s bedroom shows how Hector integrated organic wood framing into the wall surrounding one of Adeline’s most prominent paintings: a large nude female figure transformed into a graceful presence by the curvilinear surround (Fig. 11).

The view of the salon/parlor shows a variety of pieces that later found their way into museum collections (Fig. 16). Adeline gave the large calling card tray in gilt copper—seen on the lower shelf of a table—to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Fig. 1). That tray was the model for the only Guimard piece purchased by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in his lifetime. Hector showed the design in gilt bronze at the Salon des Artistes Décorateurs in 1911, from which the museum purchased it. The salon includes several Guimard metal picture frames, one cast with a replica of his signature. The signature’s prominence suggests the frame was a pre-existing design, part of Hector’s le style Guimard branding program. The frame later came to the Cooper Hewitt holding its photo of Hector (Fig. 13). Embroidered curtains conforming to the curved windows appear to be some also now at the Cooper Hewitt.

The completed Hôtel Guimard was inaugurated as the couple’s residence with a house-warming party in May 1913, but the good times did not last long.10 With the start of World War I, Hector’s relationships with high-end modelers, such as Philippon, which produced Adeline’s swirling writing seal (Fig. 17), and foundries like Maison Cottin, which produced the opulent doorbell pull for the front door (Fig. 20), could not be maintained, and orders dwindled.

During World War I, Hector’s socialist and pacifist activities took precedence. While he became more involved in politics, Adeline organized charitable efforts for the aid of wounded soldiers, among them drawing portraits that she sold for the cause. After the war, Hector designed mass housing, while Adeline continued making art. She exhibited her portraits in a 1922 show she advertised with posters.11 In 1930 the Guimards moved into a Hector-designed apartment building in which they invested, but there are no interior photos. Although they continued to house the business effects at Hôtel Guimard, it seems clear they were rarely there.

Later in the decade, as the rise of the Nazis clouded Europe’s horizons, Adeline took bold action. She reinstated her American citizenship, listing herself on documents as “Hebrew” and Hector as an ailing “refugee.” The couple fled Europe, sailing in 1938 to New York. They took a few of their more treasured possessions, leaving others in storage.12

Hector did not revive his professional life in New York, and he died there in May 1942 at age seventy-five. Adeline continued to draw. In November 1943 she had an exhibition at the Arthur U. Newton Galleries of her portrait drawings, including those of eminent sitters such as Ruggero Leoncavallo and Ignacy Jan Paderewski. But as the war was ending in 1945, her correspondence with Museum of Modern Art director Alfred H. Barr Jr. shows Adeline turned her attention to the quest to secure her husband’s legacy in earnest.

In both the US and later France, Adeline’s modus operandi in the search for suitable museum homes for Guimard works was to find one contact and get his referrals to others. Fortunately, in the US, she had Barr as her first sympathetic ally. Hector Guimard himself had initiated the connection, having written from France in 1936 about an exhibition at MoMA that included his works.13 Barr appreciated Guimard’s impact on modern art and design. His good will had encouraged Madame Guimard to resume relations. After Barr directed her to a couple of curators, notably Calvin Hathaway at the Cooper Hewitt (then known as the Cooper Union Museum for the Arts of Decoration), Adeline made commitments to specific donations to MoMA and Cooper Hewitt before traveling to France in 1948.14 Her intention to bring items to the US is validated by a 1938 inventory of objects intended for shipment from France to the US that year, but which remained in storage until after the war.15

In France, Adeline had hoped to fulfill the couple’s fondest desire to see the creation of a Musée Guimard there, but with interest in art nouveau still at a nadir, her petitions to French government officials were rejected.16 However, she succeeded when she wrote to the director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, city of Hector’s birth. He accepted a gift of the suite of furnishings from her bedroom at the Hôtel Guimard, complete with her painting of the female nude, to re-install there.17 Yves Bizardel, director of the Beaux-Arts Museum of the City of Paris, was able to accept the Guimards’ dining room suite, now installed in the Petit Palais.

Adeline left Paris in mid-July 1948, never to return. She continued making donations to US museums until the late 1950s. Starting in 1965, when the taste for art nouveau was again on the rise, her nephew Laurent Oppenheim Jr., to whom she had bequeathed most of her Guimard designed jewelry, gave it to MoMA over time. This ultimate symbol of the Guimards’ personal partnership thus became the final gifts from their possessions in le style Guimard.

Madame Hector Guimard, as she preferred to be called when she gave works, was more than a donor. She was a true and persistent champion for Hector’s genius. Her impact is still being felt: her gifts demonstrate that Guimard was the most fluid of all French art nouveau designers and document his progressive interest in design reform that connects him to modern architecture. She knew how important both his lavish custom designs and his designs for massproduction were to him, and thus to his legacy. These designs now co-mingle in museums to inform the story of a designer committed to new styles and ways of thinking, making for a much wider understanding of Hector as an early modern architect, and of Adeline as the woman who enabled us to see that.

1After Lévy ’s death, she studied with Albert Maignan (1845– 1908) and with Joseph Bail (1862–1921). 2 The original painting is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, as indicated by an inscription in German on the back of the plate. 3 Bruno Montamat, “Adeline Oppenheim Guimard (1872–1965), artiste et mécène,” Généalo-J: Revue française de généalogie juive, no. 131 (Fall 2017), p. 4. This article is a key source, based on private archives, about the wedding and Adeline Oppenheim Guimard’s family and family relationships. it cites the marriage contract, drawn up chez M. Moreau on February 12, 1909, just five days before the couple’s wedding. 4 Ibid., p. 5, which cites the sum in the contract as being 250,000 French francs in gold. 5 Ibid., p. 4. The embroidered collar from the wedding coat and lace panel from the wedding dress are now at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, and the engagement ring is at the Museum of Modern Art. 6 Sermon of the Abbeé Bellanger, Adeline Oppenheim Guimard Papers, MSS Coll 1264, New York Public Library, cited in Montamat, “Adeline Oppenheim Guimard (1872–1965), artiste et mécène,” p. 4. 7 Adeline and Hector made a brief trip to New York around the time of her father’s death in 1912. It appears likely that there may have been some additional funds that came from Edouard Oppenheim’s estate at this time, that could have provided more funds for additional decorative projects in the house. 8 A copy of the catalogue, Lustre Lumière: Nouvel Appareil Electrique, Brévété et à l’Étranger, published by Langlois et Cie, Paris, c. 1900, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Thomas J. Watson Library, gift of Mrs. Hector Guimard. 9 Millot’s display at the 1900 Paris World’s Fair included stands designed by Guimard that may be his earliest example of a specifically feminine design, something he came back to in his jewelry and accessories for Adeline. 10 Georges Vigne, Hector Guimard: Architect Designer, 1867–1942 (New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2003), p. 251. 11 The exhibition was at Lewis and Simmons gallery in the Place Vendôme. 12 Montamat, “Adeline Oppenheim Guimard (1872–1965), artiste et mécène,” p. 12. 13 Hector Guimard to Alfred H. Barr Jr., March 10, 1936, MoMA Exh. 55.4, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Some photos and architectural drawings by Guimard had been included in the 1936 exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism. See Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, ed. Alfred H. Barr Jr. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1936), p. 240, and illus. nos. 661 and 662. 14 Alfred H. Barr Jr. to Adeline Guimard, May 1, 1945, Adeline Oppenheim Guimard Papers. In this letter Barr lists Cooper Union, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Avery Library, Columbia University as possible donation institutions. The contact with Philadelphia was not made until later. 15 The inventory is in the Adeline Oppenheim Guimard Papers. 16 Ironically, this year, there is a proposal by le Cercle Guimard and Fabien Choné for a Guimard museum to be created in the Hôtel Mezzara, a house of about the same date as the Hôtel Guimard, and not far away from it. 17 Curator René Julien to Adeline Guimard, June 9, 1949, Adeline Oppenheim Guimard Papers. He thanks her for the donation and lets her know about the intended installation at the Lyon museum.

SARAH D. COFFIN is an independent decorative arts and design consultant, curator, and lecturer. She was formerly a senior curator and the head of the Product Design and Decorative Arts department at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She contributed to the book Hector Guimard: Art Nouveau to Modernism, and, with independent curator David Hanks, initiated plans for the related exhibition.