Fig. 1. Edith Dimock (1876–1955), c. 1902. NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, Florida, bequest of Ira D. Glackens.

William Glackens was regarded as a modern artist by the standards of his day; the woman he married would have been considered thoroughly modern even by the standards of our own. Edith Dimock Glackens (Fig. 1) was a wife, lover, muse, willing partner in William Glackens’s work, and a skilled artist in her own right. She was a significant determinant in her husband’s career, but other than in the indispensable personal writings of their son Ira,1 Edith Glackens is perfunctorily summarized as an heiress and a feminist. These attributes are accurate, but they are insufficient. She should be viewed as the creative and unconventional spirit that she was, as well as a profound contributor to the social and economic conditions that shaped William Glackens’s life and art.

Fig. 2. Portrait of the Artist’s Wife by William Glackens (1870–1938), 1904. Signed “W.Glackens” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 74 3/4 by 40 inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, gift of Ira Glackens in memory of his mother, the former Edith Dimock of Hartford.

Edith Dimock was born in Hartford, Connecticut, on February 16, 1876, one of six children of Ira and Lenna Demont Dimock. Ira Dimock was a successful inventor and manufacturer. Lenna Dimock believed that women should have the same privileges as men and denounced anyone who referred to “woman’s frailties.”2 Her two daughters, Edith and Irene, absorbed her beliefs.

The Dimocks lived in an enormous mansion in the prosperous suburb of West Hartford, but Lenna Dimock was uninterested in having her daughters make debuts: instead, she valued academic and cultural education. After she graduated in 1895 from Miss Brown’s Boarding and Day School in New York,3 Dimock defied even her liberal parents’ expectations and announced that she would become an artist.4 She enrolled in the Art Students League of New York in October 1895 and studied there through 1898, taking classes in life and cast drawing, composition, anatomy, and painting.5 She then returned to Connecticut and studied painting with William Merritt Chase, who was giving weekly classes in Hartford in 1900.6 Dimock realized that one class a week was insufficient, and wanted to return to New York to study with him there. She argued her case to her parents by singing the passage from Gounod’s Faust, wherein Faust begs Mephistopheles,

I want my youth! Give me youthful pleasure,

a maiden’s caress and desires.

Give me the glowing strength of youth…!

Ardent youth! Give me its desires, its intoxication, and its

pleasures!7

The senior Dimocks acquiesced. Anyone who could declare that she wanted to traipse off to the fleshpots of New York, and win her adversaries to her vocational choice by invoking those forbidden pleasures, was obviously someone of remarkable force, but by then Dimock was adept at debating equal rights.

Fig. 3. Portrait of Edith Dimock Glackens by Robert Henri (1865–1929), 1902–1904. Signed “Robert Henri” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 77 ¼ by 38 3/8 inches. Sheldon Museum of Art, Lincoln, Nebraska, Nebraska Art Association, gift of Miss Alice Abel, Mr. and Mrs. Gene H. Tallman, the Abel Foundation, and Mrs. Olga N. Sheldon.

In early 1901 Dimock met William Glackens (Fig. 4). She was attracted to the handsome artist, but he was quiet and distant, and she later confessed that she chased him. Their relationship was probably given a further push in 1901, when Robert Henri, Glackens’s early mentor, took a studio in Dimock’s apartment building. She formed her own friendship with Henri, and in November 1902 he began her portrait. He didn’t finish it until May 1904 (Fig. 3), by which time the title “Portrait of Miss Edith Dimock” had to be changed. She became Edith Dimock Glackens on February 16, 1904—her twenty-eighth birthday.

Many decades later, the art historian Bennard Perlman characterized the subject of Henri’s portrait as “a demure socialite from Hartford.”8 This description infuriated Ira Glackens, who stated that his mother was never “demure,” and not a “socialite.”9 Indeed, even Henri, regarding the liberated and exuberant Dimock, said to her about the picture, “It’s an antique, isn’t it?”10 He must have seen that the image and approach were too reticent, because they failed to convey the impact of Dimock’s personality. In contrast, John Sloan got it right when he summarized Dimock as “gracious and used her very unique, clever wits to good purpose.”11 Glackens was the retiring one of the pair, and Dimock was resolved to break down his reserve. In a letter to her before they married, he wrote of “his miserable shyness” and envied her “delightful way of carrying off things in a quasi-light style that I like so much.”12 Nevertheless, Glackens continued to call her “Miss Dimock” until she threatened, “If you call me that again, I will kiss you in front of everyone.”13

Fig. 4. William Glackens, c. 1904. NSU Art Museum, Ira D. Glackens bequest.

Glackens’s portrait of Dimock (Fig. 2), painted in spring 1904, is truer to the personality of the woman before him than Henri’s canvas. Dimock wears an elaborate outfit, redolent of wealth and status. However, her amused expression as she eyes her new husband and watches him work, affectionately taking his measure, suggests that her costume did not overwhelm her in the least. Indeed, the hint of iconoclastic humor and sense of will give the portrait its enduring magnetism.

Fig. 5. Country Girls Carrying Flowers by Edith Dimock (1876–1955), c. 1905–1912. Signed “E.Dimock” at lower right. Watercolor and black crayon with graphite on thick wove paper, 9 ½ by 10 3/8 inches. Barnes Foundation, Philadelphia, © 2017 The Barnes Foundation.

Dimock also takes center stage in Glackens’s The Shoppers which trumpets her essentiality to his life and work. Writing when he is in New York and sheis in West Hartford, Glackens reports his frustration—he’s “spoiled” The Shoppers and can’t fix it without her.14 Their marriage infused him with confidence: within months of their wedding, Glackens began using bigger canvases. The two largest paintings in his oeuvre—The Shoppers and Family Group—are multi-figural canvases in which Dimock is key. Only slightly smaller but equally ambitious is Artist’s Wife and Son. Romance and domesticity supported Glackens’s artistic project.

But what of Edith Dimock the artist? This aspect of her biography must remain speculative on account of a sad fact. After Glackens died, Dimock was so grief-stricken that she destroyed as much of her own work as she could. Anything surviving had been sold, given to other people, or was overlooked.15 Therefore, it is impossible to discuss with authority a body of work based roughly on one painting, about sixty known watercolors, and reproductions of forty-eight book illustrations. Yet even with such limitations in mind, it is possible to trace the scope of Dimock’s art.

Fig. 6. Mother and Daughter by Dimock, c. 1913. Signed “E.Dimock” at lower left. Watercolor, gouache, and charcoal on paper, 8 by 9 ¼ inches. Courtesy Bernard Goldberg Fine Arts, LLC.

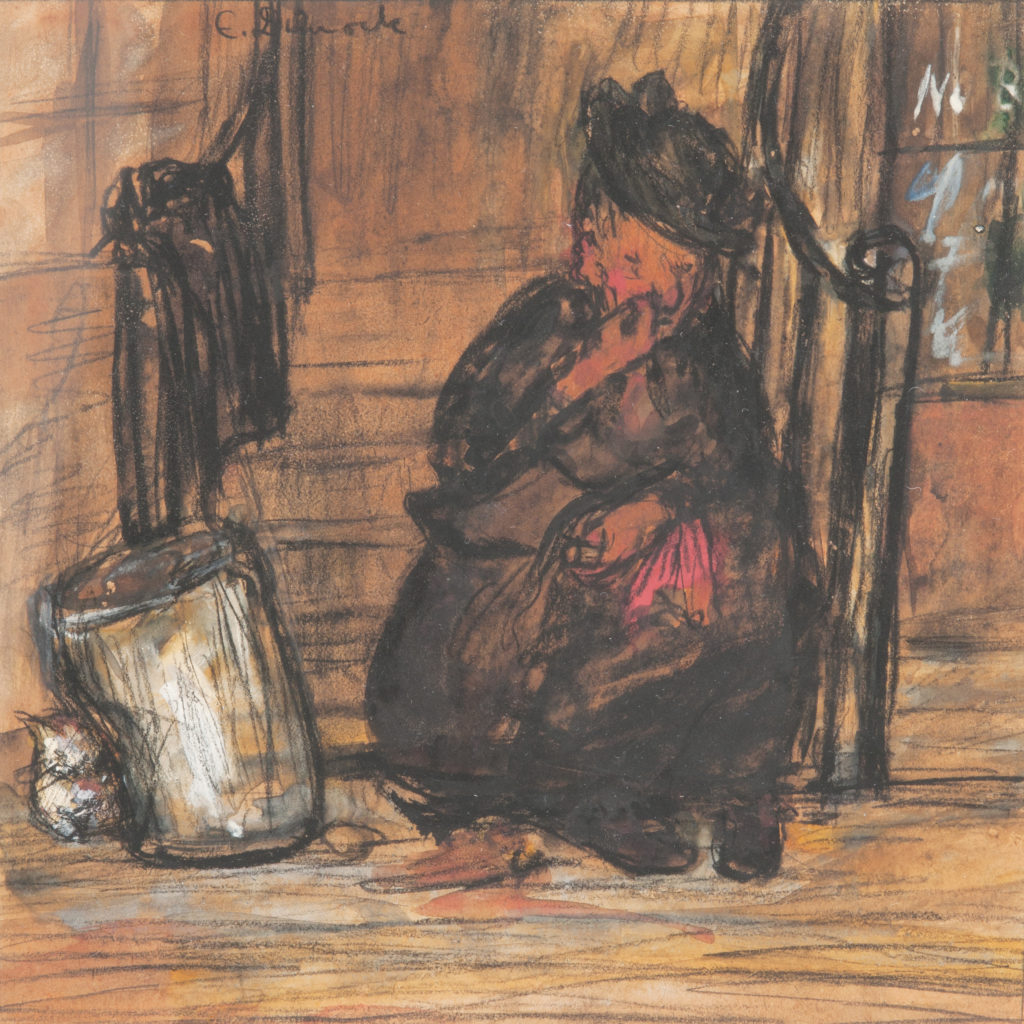

By 1903 Dimock understood that her métier was watercolor, and she would work in watercolor, enhanced by touches of gouache and black crayon, for the rest of her life. The medium was a vehicle for genre vignettes and character studies. Satirical and sharply observed, they chronicle women and children of the lower and middle classes out shopping, talking, walking, and usually seen in motion. Dimock excels at the quickly noted impression—the images are fresh, the colors pulsate, the simplifications of modern art are embraced, and the chosen medium is adeptly handled. Her talent is apparent in two watercolors (Figs. 5, 9) purchased by collector Albert C. Barnes in January 1913. (Barnes bought four watercolors from Dimock over the years.)

In April 1904, a month or so after her wedding, Dimock, who exhibited as “E. Dimock” rather than Edith Glackens, submitted three works to the American Watercolor Society’s annual spring exhibition.16 However, the published catalogue lists only one, called Rain.17 The New York Evening Sun applauded Rain (Fig. 12) as distinct from the other 344 works on view that were scorned as a sea of “friendly nothings” chosen by a “decorous” jury. Surprisingly, Dimock’s work escaped rejection:

[I]t has no business in an exhibition that ranges in orthodox order from the flimsy sketch of vague sentimental possibilities to the carefully niggled ideal of the Christmas supplement. Miss Dimock is not orthodox at all. She comes to her world very unconventionally, free from pictorial prejudice. . . . Here is an artist with a definite aim, a keen fresh vision readily interested in the humorous, whimsical aspect of her neighbors. . . . And these little fragments are picked out with an astonishing eye to . . . the business in hand: the blobs of color distributed artfully and with a frugal recognition of form, no more nor less than sufficient to enclose and intensify the curiosity, oddity or quaint charm of the characters. . . . How futile are the many careful, conscientious studies on the walls here in comparison with this slight sketch that goes so infallibly to the point!18

Contrary to assertions in previous publications,19 Dimock did not sacrifice her artistic career to marriage. (Indeed, if that had been true, there would have been precious little career to give up, because her first known professional activity—having eight watercolors in the seventy-second annual exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts—occurred in 1903.) Dimock created the cover and illustrations for the 1905 children’s book The Yellow Cat and Her Friends, by Grace Van Rensselaer Dwight, a friend who was also from the Hartford elite.20 But there were competing claims on Dimock’s time, especially after her children Ira and Lenna were born in 1907 and 1913. The Glackenses had servants and everything was cushioned by her money, but Dimock had a busy establishment to manage.

Fig. 7. Fine Fruits (Group) by Dimock, c. 1913. Signed “E.Dimock” at lower right. Watercolor, gouache, and charcoal on paper, 8 by 9 ¼ inches. Courtesy Bernard Goldberg Fine Arts, LLC, New York.

Glackens’s marriage to Dimock changed his financial circumstances from parlous to secure, and thus the trajectory of his art. Although Dimock did not then have the fortune that she would inherit when both parents died in 1917, her income enabled the couple to live in far greater comfort than they would have on Glackens’s earnings alone, and he was free of the financial pressures that plagued his friends. Yet Glackens continued to illustrate and did not exploit his wife’s money. Her wealth made a bourgeois household possible, and his income supported his studio and exhibition expenses. Most artists in the Glackenses’ circle could not afford to support a family, and those who did, struggled. Dimock and Glackens had no anxiety about their children’s upbringing, and they lived in the commodious and lavishly furnished apartments that are seen as backgrounds in Family Group and Artist’s Wife and Son.

Fig. 8. Three Women (Group) by Dimock, c. 1913. Signed “E.Dimock” at lower center. Watercolor, gouache, and charcoal on paper, 8 by 9 ¼ inches. Courtesy Bernard Goldberg Fine Arts, LLC.

Another vital commitment was women’s rights. In 1909 Sloan wrote, “Mrs. G. is for women’s suffrage which is growing nearer and nearer each year.”21 Both she and Glackens marched in the suffrage parade of 1913. In 1911 and 1915 she was appointed honorary secretary of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, an umbrella organization for more than one hundred British groups dedicated to obtaining the vote for women.22 Therefore, the record of Dimock’s exhibition history that follows is a testament to the considerable energies she invested in sustaining a career.

Fig. 9. Country Girls by Dimock, c. 1905–1912. Signed “E.Dimock” at lower right. Watercolor, gouache, and black crayon on wove paper, 8 by 9 ¼ inches. Barnes Foundation, © 2017 The Barnes Foundation.

In April 1910 Dimock and Glackens participated in the Exhibition of Independent Artists, the first large-scale invitational show for progressive artists. Her watercolors of New York life depicted women and children from the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village, and the denizens of the latter group were drawn from the Italian neighborhood a few blocks south of the Glackenses’ apartment on Washington Square.23 Dimock remained a disciple of the Ashcan school long after Glackens had jettisoned it, specializing in urban incidents and studies of people on the margins of society. The 1910 annual of the American Water Color Society, held from April 28 to May 22, overlapped the Independents show, and six of Dimock’s pieces were accepted.24 They too hint of Ashcan roots: each was titled Street Group. Dimock had two watercolors in the society’s 1911 annual, which traveled to Detroit and Chicago.25 She illustrated Stories Grandmother Told, a book of fairy tales published in 1912 (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Illustration by Dimock for “The Queer Brownie,” in Kate Forrest Oswell’s Stories Grandmother Told (Macmillan, New York, 1912), p. 52. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

In February 1913 Dimock, like her husband, was in the International Exhibition of Modern Art, known as the Armory Show. All eight of Dimock’s watercolors sold. Sweat Shop Girls in the Country and Mother and Daughter (Fig. 6) were purchased by John Quinn, then the leading collector of modern art in America. The other six, all titled simply Group, were sold to a George E. Marcus, who has not been identified.26 Two of those six watercolors have disappeared, but four emerged with new titles: Fine Fruits (Fig. 7); Three Women (Fig. 8); Florist; and Bridal Shop.27 In May 1913 Dimock exhibited at the MacDowell Club, along with Glackens, Sloan, Henri, James and May Wilson Preston, Mahonri Young, and John White Alexander.28 In April 1915 she was in the first exhibition of the American Salon of Humorists,29 and in early 1918 both she and Glackens became charter members of the Whitney Studio Club,30 a forerunner of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Dimock participated in the Society of Independent Artists’ annual exhibitions in 1920, 1924, 1925, 1928, and 1929.31

Fig. 11. The Old Snuff-Taker by Dimock, 1912. Signed “E. Dimock” at upper left. Watercolor, charcoal, graphite, and gouache on paper, 7 inches square. NSU Art Museum; Ira D. Glackens bequest.

In February 1928 Dimock had a show at the Whitney Studio Club. The exhibition of fifty-two watercolors produced in the mid-1920s again disproves the canard that Dimock had given up painting. Her last known solo exhibition took place in March 1934. Four years later, Glackens died and Dimock devoted herself to burnishing his legacy. She kept his 1904 portrait of her nearby until her death on October 28, 1955. It is no wonder why. The painting immortalized Dimock’s inextinguishable self— “diverting, unpredictable, determined, vigorous, and full of will.”32

Fig. 12. Rain by Dimock, c. 1904. Signed “E.Dimock” at lower left. Watercolor, charcoal, graphite, and gouache on paper, 6 ½ by 8 inches. NSU Art Museum, Ira D. Glackens, bequest.

AVIS BERMAN is an independent writer and art historian. This article was adapted from her essay in The World of William Glackens, Vol. II. The C. Richard Hilker Art Lectures & New Perspectives on William Glackens (Sansom Foundation, New York, 2017). This excerpt is published courtesy of the Sansom Foundation.

1 Most notably, Ira Glackens (hereafter IG), William Glackens and the Ashcan Group (Grosset & Dunlap, New York, 1957); IG, “A Garden of Cucumbers” [also recorded with variations on this title], unpublished manuscript, 1970s–1980s, William J. Glackens Research Collection and Study Center, NSU Art Museum, Fort Lauderdale (hereafter WJG/ NSU); and IG, Ira on Ira: A Memoir (Tenth Avenue Editions, distr. Writers and Readers Publishing, New York, 1992). 2 IG, William Glackens and the Ashcan Group, p. 34. 3 “Mrs. Glackens, 79, Widely Known in Art Circles, Dies,” Hartford Courant, October 29, 1955; “Mrs. W.J. Glackens Passes in Hartford,” The Villager, date unknown (October 1955); clippings in WJG/NSU. 4 To avoid confusion with her husband, Edith Dimock Glackens will henceforth be referred to as “Dimock,” the name she used professionally. 5 Art Students League of New York records for Edith Dimock, Art Students League Archives, New York. 6 Chase scholar D. Frederick Baker, email to author, December 7, 2012. 7 IG, “A Garden of Cucumbers,” p. 52. 8 Bennard B. Perlman, Robert Henri, Painter (Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, 1984), p. 81. 9 IG, conversation with the author, mid-1980s. 10 IG, “The So-called Ash Can School,” lecture, WJG/NSU, p. 20; IG, William Glackens and the Ashcan Group, p. 62. 11 Entry for November 30, 1908, in John Sloan’s diary, quoted in John Sloan’s New York Scene: From the Diaries, Notes, and Correspondence 1906–1913, ed. Bruce St. John (Harper and Row, New York, 1965), p. 267. 12 Quoted in IG, William Glackens and the Ashcan Group, p. 44. 13 Ibid., p. 44. 14 Ibid., pp. 84–85. 15 IG, Ira on Ira, p. 3. 16 Records of the American Water Color Society 37th Annual Exhibition, microfilm reel 497, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (hereafter AAA). 17 Illustrated Catalogue of the Thirty-Seventh Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society (American Water Color Society, New York, 1904), p. 11. 18 [Charles FitzGerald], “The American Water Color Society,” Evening Sun, May 3, 1904, n.p., Charles FitzGerald scrapbooks, c. 1901–1918, AAA. 19 See, for instance, Laura R. Prieto, At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2001), p. 260, n. 46. 20 Dwight became even friendlier with Dimock and Glackens after she married Daniel H. Morgan, moved into the Glackenses’ apartment building, and posed for Family Group. 21 Entry for November 15, 1909, in Sloan’s diary, in John Sloan’s New York Scene, p. 352. 22 Space does not permit an investigation of Dimock’s involvement with the women’s suffrage movement in England, but the connection may well have started with her mother, a native Briton and feminist. Further twelve more, activism for women’s suffrage was more organized, more advanced, and more militant in England. 23 See The Fiftieth Anniversary of the Exhibition of the Independent Artists in 1910 (Delaware Art Center, Wilmington, 1960), p. 10. 24 Forty-Third Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society (American Water Color Society, New York, 1910), pp. 27–28. 25 Illustrated Catalogue of the Forty-Fourth Annual Exhibition of the American Water Color Society (American Water Color Society, New York, 1911), pp. 11–12; Elizabeth Thompson Colleary, The William J. Glackens Collection in the Museum of Art / Fort Lauderdale (Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale Nova Southeastern University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, 2014), p. 100. Colleary also discovered that Dimock was in a group exhibition at the Thumb Box Gallery in New York City in March 1916. Her watercolors were of “east side life,” and co-exhibitors included George Bellows, Maurice Prendergast, and Glackens. 26 See Milton W. Brown, The Story of the Armory Show (Abbeville Press/Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation, New York, 1988), p. 262. 27 The Armory Show at 100: Modernism and Revolution, ed. Marilyn Satin Kushner and Kimberly Orcutt (New-York Historical Society, New York, 2013), pp. 440–441. 28 “Art at Home and Abroad: An Exhibition of Drawings, &c., Which Shows Present-Day Tendencies of American Art,” New York Times, May 11, 1913, p. 14. 29 Emanuel Julius, “Humor in American Art,” New York Call, May 2, 1915, p. 1. 30 “Charter Members Whitney Studio Club,” typed list, Frances Mulhall Achilles Library, Archives, Whitney Museum of American Art. 31 Clark S. Marlor, The Society of Independent Artists: The Exhibition Record 1917–1944 (Noyes Press, Park Ridge, NJ, 1984), p. 210. 32 IG, “A Garden of Cucumbers,” p. 414.