Detail of Dark Bathroom by Francis Glessner Lee, c. 1944–1948. Mixed mediums; height 11 3/8, width 15 ¼, depth 20 7/8 inches overall. All objects illustrated are from the collection of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, courtesy of the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Baltimore, Maryland.

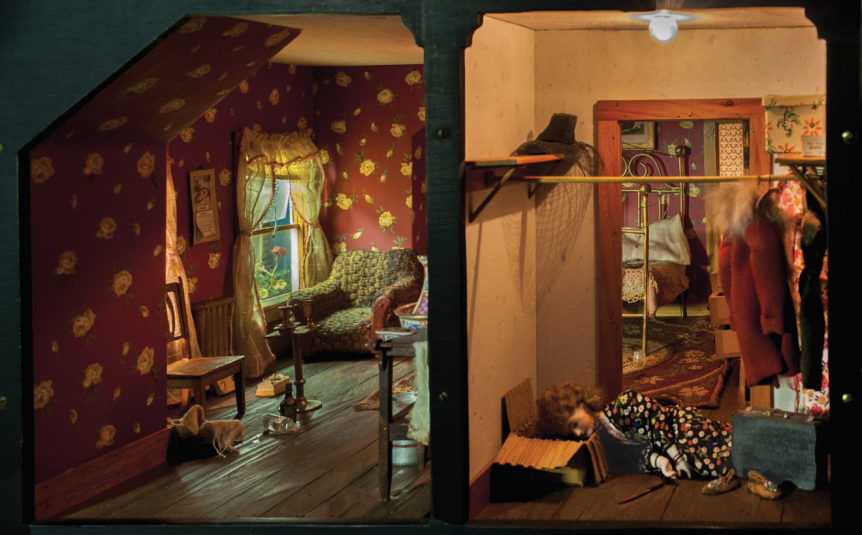

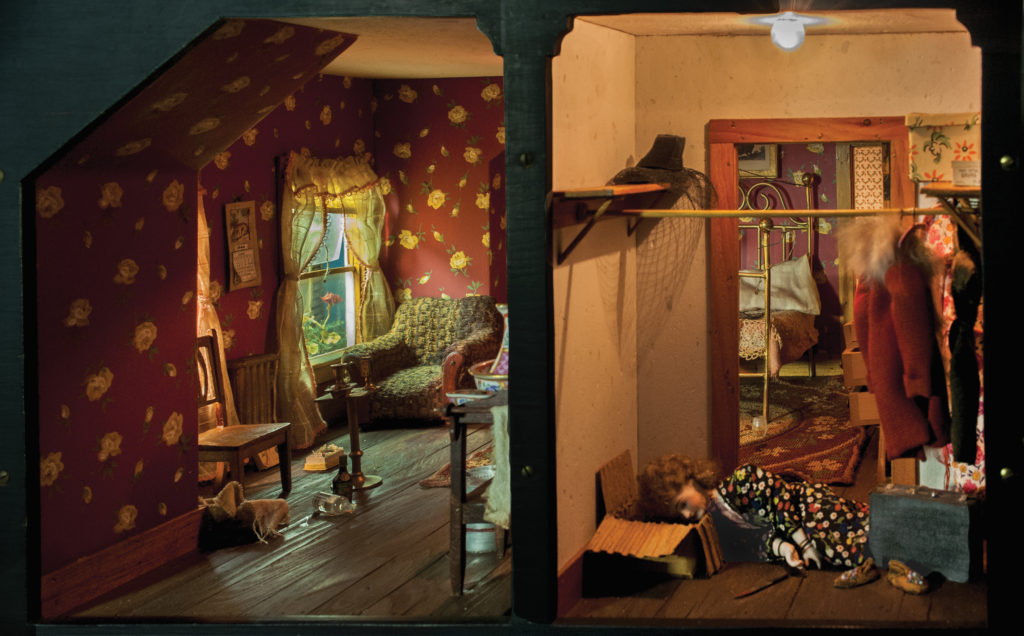

The crime scene is littered with potential clues. The body of Marie Jones lies in a walk-in closet, her throat slashed, her head resting on a cardboard box. A knife is on the floor next to her. Are those bangles she is wearing, or have her wrists been bound? All the drawers of the dresser are open, and a suitcase sits nearby. The adjacent room is furnished with an upholstered chair, a brass bedstead, and a washstand. Its walls are papered in a red floral pattern. Two liquor bottles stand on the floor, alongside an open box of candy and a rag covered in what may be blood. But perhaps the most perplexing aspect of this tableau is that it occupies a wooden box about two feet on a side.

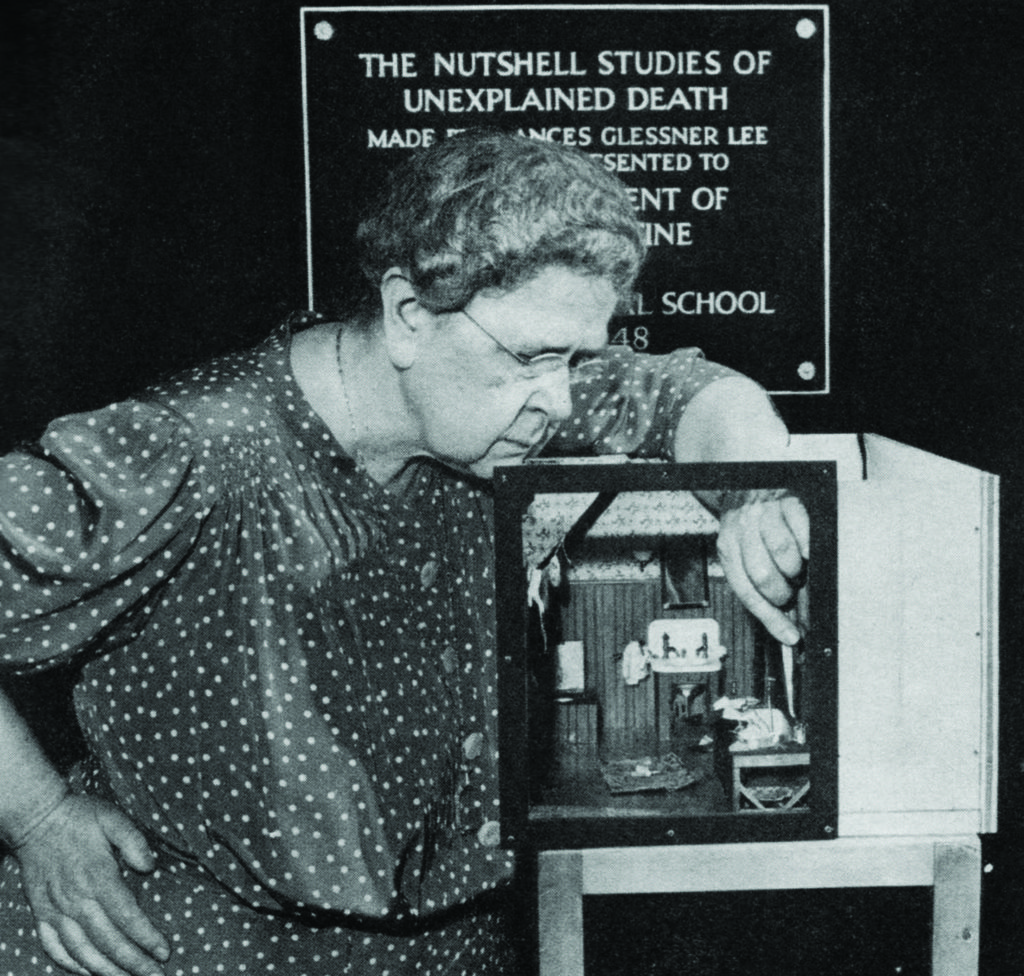

Frances Glessner Lee (1878–1962) with her Nutshell diorama Dark Bathroom. Photograph courtesy of the Glessner House Museum, Chicago.

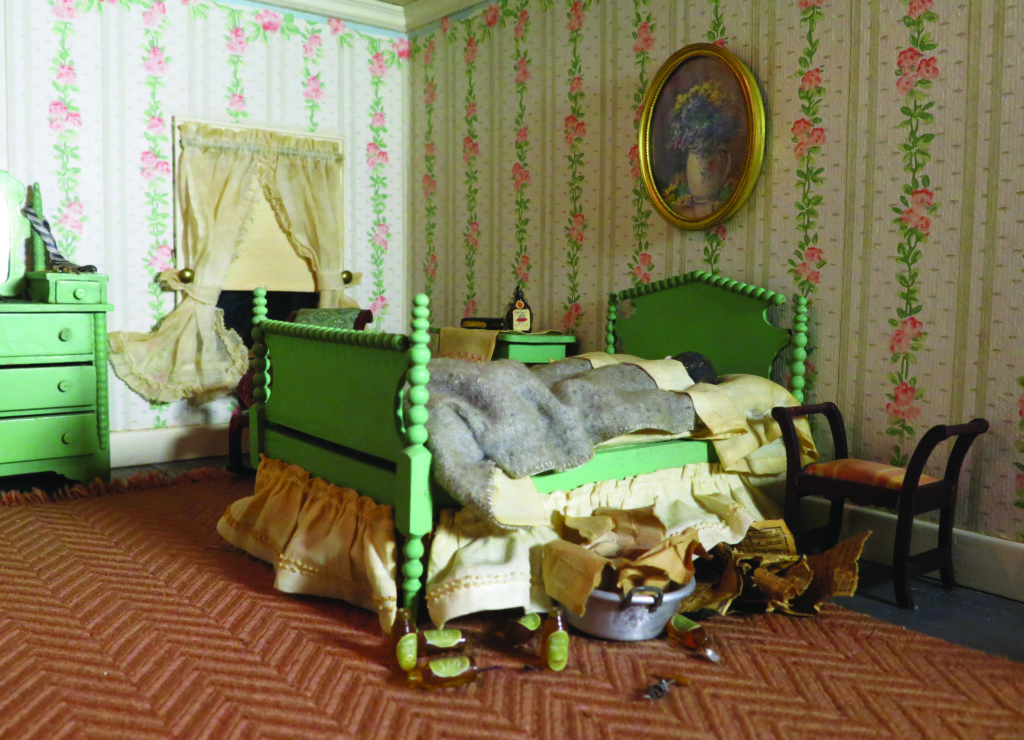

The composition, known as Red Bedroom, is one of nineteen exquisitely detailed miniature death scenes made by amateur criminologist Frances Glessner Lee. Lee called her creations The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. She built them in the 1940s and ’50s to train homicide investigators to canvass a crime scene properly and uncover evidence in order to “convict the guilty, clear the innocent, and find the truth in a nutshell.” These dollhouse-size dioramas of true crime scenes helped revolutionize the emerging field of forensics and are still used as training tools today at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in Baltimore. Lee was an exacting and talented miniaturist, and she masterfully crafted handmade and customized elements to render scenes in precise detail, with each component a potential clue designed to challenge trainees’ powers of observation and deduction. Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, an exhibition at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, examines these tableaux as artifacts at an unexpected intersection between craft and forensic science. Murder Is Her Hobby reveals how Lee, considered the godmother of forensic science, co-opted traditionally feminine crafts not only to advance a male-dominated field, but to become one of its leading voices.

- Attic, c. 1946–1948. Mixed mediums; height 21 ¾, width 17 1/8, depth 12 7/8 inches.

- Detail of Attic, c. 1946–1948. Mixed mediums; height 21 ¾, width 17 1/8, depth 12 7/8 inches.

Born in Chicago in 1878 to John and Frances Glessner, Frances was heiress to the International Harvester fortune. From an early age, she had an affinity for mysteries and medical texts. Despite academic leanings, she did not attend college, and instead followed the more conventional trajectory for women of that era: at nineteen she married a young lawyer named Blewett Lee. Assuming the role of affluent wife and mother, she pursued appropriate feminine pastimes, planned parties, and attended philanthropic events, but grew unhappy. After sixteen years and three children, the marriage dissolved.

- Detail of Three-Room Dwelling, c. 1944–1946. Mixed mediums; height 12, width 32 ½, depth 32 7/8 inches overall.

- Detail of Three-Room Dwelling, c. 1944–1946. Mixed mediums; height 12, width 32 ½, depth 32 7/8 inches overall.

During and after her marriage, Frances’s morbid fascinations persisted, and she found a kindred spirit in George Burgess Magrath, whom she met in the summer of 1898. Magrath studied medicine at Harvard, specializing in death investigation, and later became chief medical examiner of Suffolk County, Massachusetts. He fueled her imagination with true tales of murder and mystery, and delighted her with his respect. Recognizing her as an equal, he confided his concerns about the young field—like the poor training of investigators who often overlooked or contaminated key evidence at crime scenes.

Barn (also known as The Case of the Hanging Farmer), c. 1943–1944. Mixed mediums; height 27, width 23 ½, depth 29 inches.

A few years after Frances’s brother passed away in 1929, she made a gift to Harvard in his honor, helping to establish the first-of-its-kind department of legal medicine. Later, in 1936, she inherited her fortune and was finally free to pursue her passion. No longer under the watchful eye of her parents and a society that disapproved of her interests, she began working with her local New Hampshire police department, earning the title of police captain—the first woman in the country to achieve that rank.

In 1943, at the age of sixty-five, she finally began work on The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death. Proving an ingenious solution to a problem Magrath had voiced years earlier, the Nutshells were equivalent to virtual reality in their time, re-creating perplexing death scenes where anything and everything was a potential clue. Carpenter Ralph Mosher built all the wooden elements, including the furniture. Lee’s handmade objects rendered scenes with exacting accuracy and meticulous detail—from real tobacco in miniature, hand-burned cigarette butts, tiny stockings knit with straight pins, and working locks on windows and doors to the angle of minuscule bullet holes, the patterns of blood spatter, and the discoloration of painstakingly painted miniature corpses.

Red Bedroom, c. 1944–1948. Mixed mediums; height 12 5/8, width 24 ¾, depth 24 5/8 inches.

The Nutshells became the centerpiece of Lee’s homicide investigation seminars at Harvard. The real cases behind them remain relatively secret. However, Lee never intended these works as “whodunits” in the traditional sense. The purpose of the exercise is to encourage thoughtful inquiry and a scientific approach. Crime-scene reports written by Lee are presented alongside each diorama, encouraging trainees to act as investigators, conjecturing: was this death the result of a homicide, suicide, accident, or natural causes?

- Detail of Log Cabin, c. 1944–1946. Mixed mediums; height 14 ½, width 18 ¼, depth 23 5/8 inches overall.

- Detail of Log Cabin, c. 1944–1946. Mixed mediums; height 14 ½, width 18 ¼, depth 23 5/8 inches overall.

While Lee drew from real cases, she embellished the original scenes with elements from her imagination and the world around her to create scenes that are as full of artistry as they are of detail and realism. The cases she selected and details she chose provide insight into the mind of this remarkable woman, and a window into the domestic history of mid-twentieth-century America. The Nutshells also testify to the determination of Captain Lee, as she liked to be called, who used her cunning and craft to break the glass ceiling and advocate for others who did not have a voice. The miniatures not only taught investigators how to properly canvass a scene but also challenged their biases. One of the first things evident in the Nutshells, aside from the corpses, is their focus on gritty working-class interiors. Lee’s scenes are caught interrupted, not in flawless tranquility but narrative disarray, teeming with the energy of their inhabitants, evidenced by half-peeled potatoes and crumpled papers. These scenes present a world far from the affluent society of Lee’s youth. Instead, Lee put herself in the shoes of the lowliest members of society—prostitutes, drunkards, and the unfortunate—seeking justice for victims whom others often dismissed, and inducing investigators to overcome prejudices in search of the truth.

- Detail of Striped Bedroom, c. 1943–1948. Mixed mediums; height 13 3/8, width 19 5/8, depth 25 1/2 inches overall.

- Detail of Striped Bedroom, c. 1943–1948. Mixed mediums; height 13 3/8, width 19 5/8, depth 25 1/2 inches overall.

The Nutshells are essentially about teaching people how to see. So much of our culture has gone digital, and that’s where craft shines, because it’s three-dimensional. You can’t really understand the genius of the Nutshells from photos on the Internet or from a flat page; you have to investigate them fully in the round. I hope Murder Is Her Hobby—the first public display of all nineteen Nutshells—will bring new levels of appreciation to the dioramas as works of art, to Lee’s particular genius, and to the importance of craft to seemingly unrelated parts of our lives.

Murder Is Her Hobby: Frances Glessner Lee and The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death is on view at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, to January 28, 2018.

NORA ATKINSON is the Lloyd Herman Curator of Craft at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.