The mantelpiece featured here is one of twelve designed for a large neoclassical Georgian house on the estate of Buckminster Park in Grantham, Leicestershire, one of the family seats of William Tollemache, ninth Earl of Dysart. In 1881 or 1882 the young Lord Dysart commissioned the architect Halsey Ricardo to completely remodel and redecorate the house.

Both an interior and decorative designer, Ricardo had trained under the noted arts and crafts architect Norman Shaw and was very mindful of the movement’s purist spirit and stress on fine workmanship. He was for a time a partner in-and is the best-known of the designers for-the ceramics firm of William De Morgan. Perhaps the eighteenth-century style of the house and Ricardo’s proclivity for pottery gave him the idea of reviving the Wedgwood surrounds of the time when the house was first built.

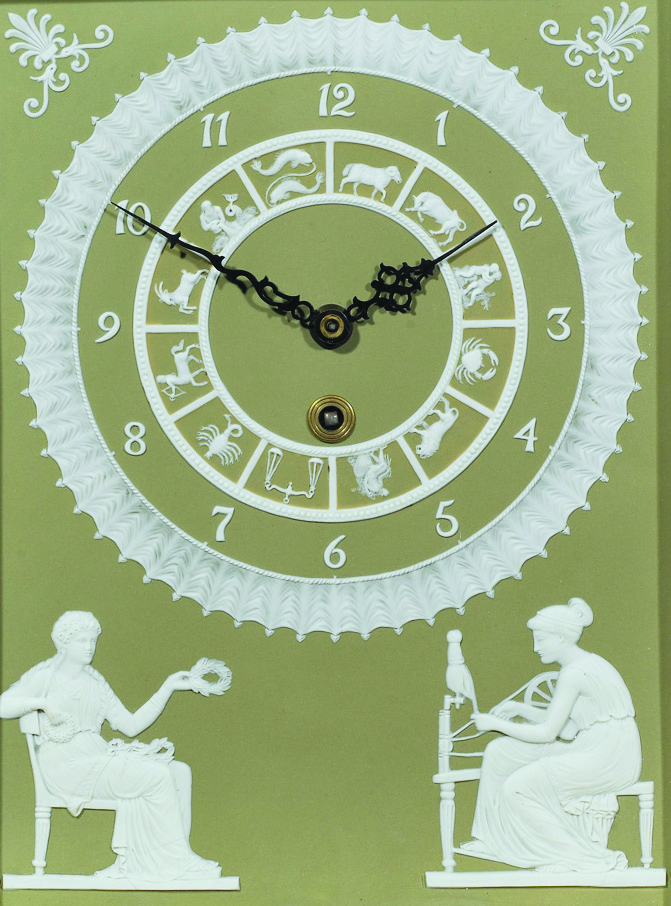

In the 1770s Josiah Wedgwood made plaques of jasperware especially for fireplace mantels and continued to improve on them. The work was expensive but a number of clients were eager to have such a neoclassical style fireplace surround. Even in Virginia, at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, there was a mantelpiece (now a reproduction) in the dining room with a large tablet and two oval plaques by Wedgwood, dating about 1786.

Ricardo’s use of Wedgwood’s jasperware plaques at Buckminster Park is the earliest record of their revival for use on a mantelpiece in the nineteenth century. His plan for the large dining room also included a frieze of oblong Wedgwood plaques above paneling that was set halfway up the walls and a large built-in sideboard to display Wedgwood jasper vases. Some of the plaques used in the room’s decorations were done in a special green that Wedgwood copied from the color scheme Ricardo had mixed for the house, which is still known as Dysart green. The designs of the plaques were based on eighteenth-century representations of classical scenes as well as portraits of Greek and Roman statesmen. The plasterwork of the ceiling was also decorated with classical ornamentation.

When the house was demolished in 1952, it was first stripped of its decorations. The dining-room mantelpiece and the room’s other accoutrements were bought by an American dealer and shipped to Philadelphia. Only the mantelpiece is known today. It was purchased by a couple in Narberth, Pennsylvania. Recently, through the generosity of members of the Bunting family, it has been acquired by the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama. With the help of photographs from the National Monuments Record, some taken in 1886 and others at the time the Dysart house was demolished, the mantelpiece is installed in a reconstructed eighteenth-century English art gallery at the museum. This gallery, which contains paintings, silver, and ceramics, forms an aesthetic link to the adjacent gallery, where the Beeson Collection, comprising some fourteen hundred pieces of Wedgwood pottery, is exhibited.

Even more recently the museum has become the happy recipient of the Buten Wedgwood Collection-more than eight thousand pieces collected in the mid-twentieth century by Harry and Nettie Buten-further strengthening the museum’s nineteenth- and twentieth-century material and making it not only the largest and most comprehensive repository of Wedgwood in the United States, but the second in the world after the Wedgwood Museum at the factory in Barlaston. This year’s 250th anniversary of the founding of Wedgwood will surely be celebrated in Birmingham.