Visiting the Oppenhimer Collection of Folk Art at Longwood University in Farmville, Virginia, requires a walk across the school’s leafy campus. Highlights from the collection are rotated in a gallery tucked away in a space that doubles as a student meeting area in the Upchurch University Center. Thanks to the pandemic, the space was empty when I visited, but the potential of the room for socializing was clear, and, indeed, was one of the chief reasons it was chosen to display the art. For William and Ann Oppenhimer, longtime collectors and co-founders of the Richmond-based Folk Art Society of America, art is all about relationships. As the gallery’s co-curator Michael Phillips explains, “the Oppenhimers had incredibly deep, personal connections to each of these artists” and the layout of the gallery—along with the inclusion of many of Ann Oppenhimer’s photos of the artists—acts as a way for students and visitors to craft their own connections to each piece as they sit, chat, or work in their midst.

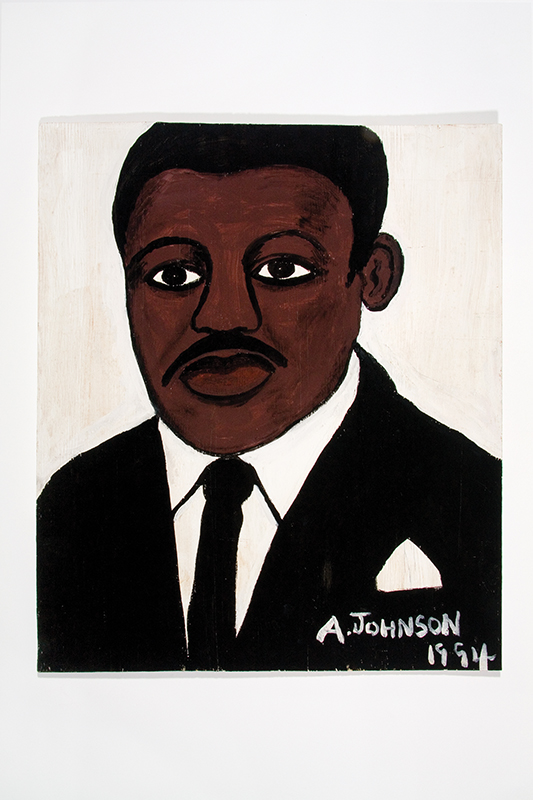

The Oppenhimers’ collection— though varied in medium, theme, and place—has a clear through line in its personal and intimate energy. Ann and William (known as “Boo”) made a point to befriend and truly know each artist they collected (the works all postdate 1950), and the gallery is the embodiment of those relationships. As Rachel Ivers, executive director of the Longwood Center for the Visual Arts, elaborates: “Ann once shared with me that she consciously avoids the exploitative collecting of work. . . . She and Boo approach folk art as the dignified creative form that it is, and they did so well before most art historians and museums did the same. They are pioneers in this regard. The works in the LCVA collection are representative not only of some of the best twentieth- and twenty-first-century folk art created, but also testament to a lifetime of friendships.”

David Whaley, the university’s design director and curator of the gallery, says: “I’ve known the Oppenhimers most of my life and was quite familiar with their collection and the objects they’ve given to Longwood. The depth and breadth of their gift is amazing.” The collection is delightfully varied, with ceramics and wood carvings arrayed alongside works on paper—many of the latter incorporating unusual materials such as mud, honey, or house paint. As Whaley notes, visitors “will find both colorfully crafted whimsy and deeply expressed emotion” throughout the collection.

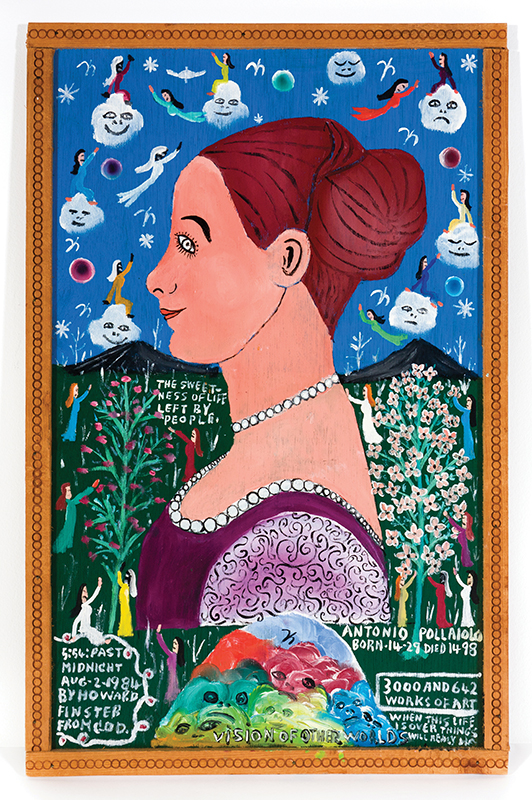

Well-known folk artists can be found in the collection, Howard Finster being one of the most notable. Phillips says that Finster, a Baptist minister, was known to “eat coffee grounds by the spoonful” as he worked with religious fervor on his paintings, all of which capture a fanatical zeal in both their content and execution. Finster felt commissioned by God to create Paradise Garden, a religious roadside grotto in Georgia that doubled as his home and workplace. For me, there is a very particular feeling—admiration, a dash of fear, a flash of recognition—that is ignited in the presence of truly devoted devotional pieces. On view in the gallery, Finster’s Antonio Pollaiolo #3642 is, in a way, a Paradise Garden in miniature, capturing all of the roadside’s energy onto a single canvas and showing how cleverly Finster incorporated the works of other artists—in this case an Italian Renaissance painter and sculptor—into works all his own. I fell in love with Finster because he took a fine art masterwork and removed it from its staid context and reinvigorated it into something new. Whether the viewer agrees with Finster’s enthusiastic endorsements of faith, they are singular pieces and enjoyable in that right alone. As Phillips asked, “Could anyone else have produced this?” The answer, it was clear to me, was “no.”

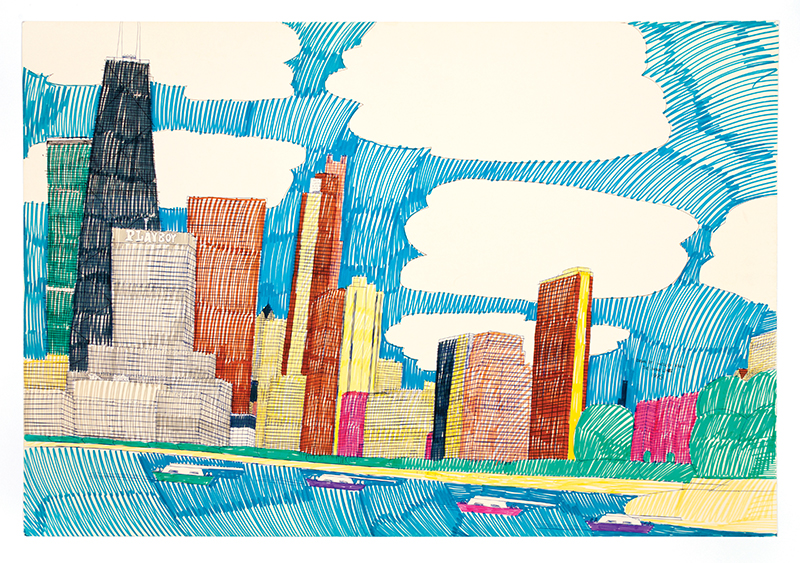

Although Finster’s work and story were the most arresting to me, each artist and object in the gallery could offer a visitor a great deal to reflect on. My boyfriend waxed poetic about The Shore Line—a drawing by the late Chicago visual artist and musician Wesley Willis—for the better part of fifteen minutes, reflecting on how it captured a vibrancy, energy, and appreciation for urban life that he was unaccustomed to seeing in other works at galleries I had dragged him to over the years. I think this is ultimately the unique power of folk art; it taps into the intimate and personal feelings we have for who we are and where we belong in ways that other works cannot. As Whaley says: “folk art is a quintessential representation of human creativity. The Oppenhimer Collection will delight both the casual viewer and the art expert alike.”

The Oppenhimer Collection of Folk Art at Upchurch University Center can be viewed by members of the public 11 am–5 pm, Tuesday–Saturday, and 1–5 pm on Sunday. Contact the Longwood Center for the Visual Arts at 434-395-2206 or visit lcva.longwood.edu for more information.

Virginia-based artist JENAMARIE BOOTS is a former editorial assistant at The Magazine ANTIQUES. She was most recently recognized for her textile art as artist-in-residence at Petrified Forest National Park in July 2019.