“My whole life is in that quilt . . . my hopes and fears, my joys and sorrows, my loves and hates. I tremble sometimes when I remember what that quilt knows about me.”

Unnamed great-grandmother of Marguerite Ickis, in Carleton L. Safford and Robert Bishop, America’s Quilts and Coverlets (New York: E.P. Dutton, 1980), p. 88.

This poetic quotation from an anonymous elder needleworker conjures up the seemingly magical power of quilts. Protecting the body, comforting the mind, transforming the old into something new: quilts serve all these profound purposes and, somehow, still do more. Pouring effort into her work day after day, the maker of a quilt sees her project grow in concert with her own changing life; imbued with this energy and the events of passing time, the pieces are vested with meaning. The final result is larger than its parts. Often handed down in a family, the quilt also takes on the role of history keeper, carrying stories from one generation to the next.

What That Quilt Knows About Me, an exhibition on view now at the American Folk Art Museum, reflects on this notion, presenting quilts and related textiles as collections of intimate stories. The idea that these objects have the capacity for “knowing”—containing information or narratives about the human experience—expands the scope of the textile beyond its maker, exploring how material things can gather, retain, and pass down histories of an individual, family, and community.

Unlike many quilt exhibitions, this one is not organized by time period, style, culture, or technique. Drawing from the museum’s collections of American textiles from across two centuries and into the present, the show offers tales of the quiltmakers themselves, as well as those of many others connected to their works. Alongside the quilts’ visual beauty and masterful craftsmanship, the viewer is invited to consider the quilt as an archive—looking within and beyond the simplicity of utilitarian function to focus on the intimacy of the human-textile relationship.

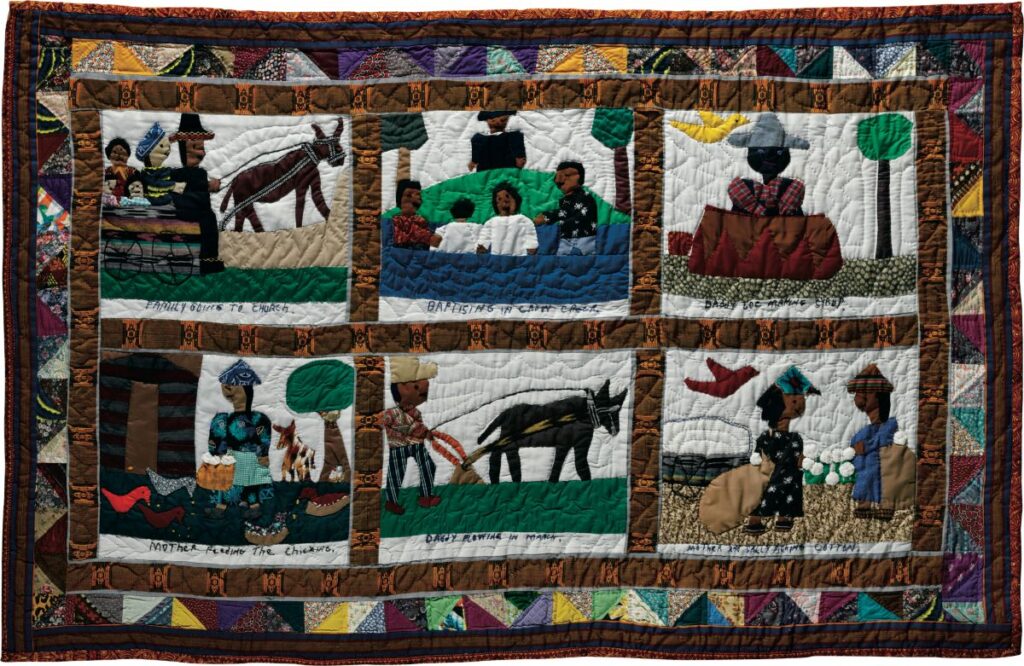

Quilts tell stories in various ways. Some are quite literal—constructed as a series of vignettes in a linear format that encourages us to follow the thread of an illustrated history. Written or stitched text might also provide labels to advance the story. One example is found in the “family history quilt” made by Hystercine Rankin in the late twentieth century (Fig. 2). Rankin learned to quilt from her grandmother, and by age twelve she was making bedcovers for her ten brothers and sisters. As a young married woman with seven children of her own, Rankin continued quilting, constructing multiple quilts to keep her family warm.

It was not until Rankin was in her fifties that her practice became pictorial. Along with elaborate star, nine-patch, and log cabin variations, Rankin became well known for her “memory quilts.” Organizing her compositions into a grid of small vignettes, she used techniques of appliqué and embroidery to create scenes of family life.

Through squares with inscriptions such as “Family Going to Church” and “Mother Feeding the Chickens,” Rankin highlights themes of hard work and religion. Her work also frequently comments on the traumas of Black life in the Jim Crow South. In one of her quilts, Black students walk to school as white children pass them riding a bus.

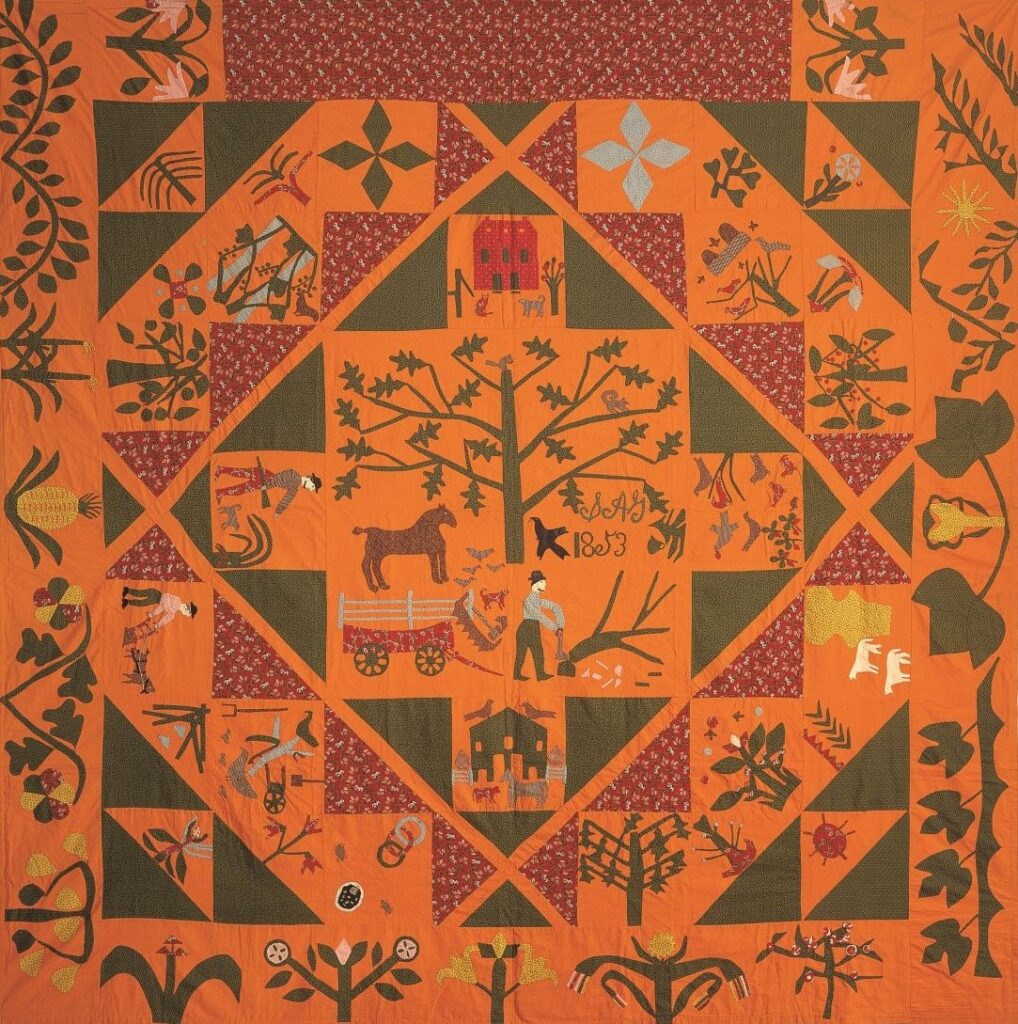

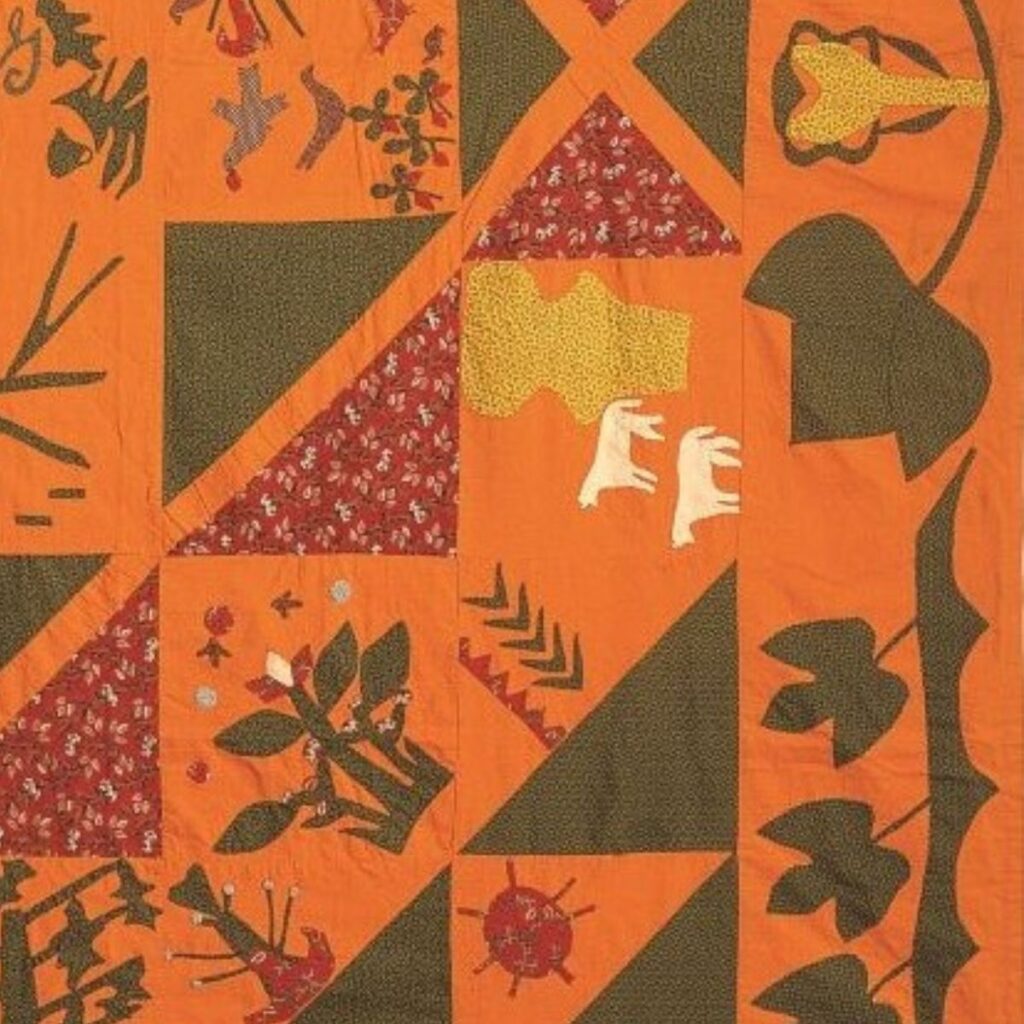

Other pictorial quilts contain mysteries, personal references that we can no longer quite decode. At center right in a quilt by Sarah Ann Garges, an amorphous yellow patch obscures a male figure (Figs. 5, 5a). Why was he covered up? Though curators at AFAM discovered this curiosity years ago, we will probably never know the quilter’s reasons for removing him from the scene. The quilter’s determination to conceal him suggests the specific and personal nature of her work. Rather than generalized figures, the characters populating her quilt may well have been intended to represent people from her life.

According to family tradition, the bedcover was made to celebrate the engagement of Sarah “Sallie” Ann Garges to her groom, Oliver Shutt. Scenes from agricultural life enliven the geometric composition, likely drawn from everyday experiences on the family farm in Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Grounding the design with a house and a barn at either end of the central diamond, Garges depicts men at work, hunting, plowing, and chopping. Distinctive motifs such as a beehive, squirrels, and bugs further personalize the scene. The quilter initialed and dated her work in the center with the year of her engagement, 1853, and signed her initials “SAG.” Garges had three brothers, but one died young, suggesting a possible candidate for the covered figure.

While some quilts are highly personal, others tell well-known stories. For example, a playful and highly engaging quilt made by Raymond Bellamy chronicles fifty-three deities, heroes, and other characters from Greek mythology (Fig. 8). Each patch illustrates a story, encouraging the viewer to participate in a game of seek and find: Icarus falls from the sky having just lost his wings; the nine Muses jump and twist, each in a different pose. The range of bright colors and the varied shapes of the patches contribute to the dynamism and wit of the composition, producing a lively expression of the joy the quilter took in both subject and medium.

Quilts often speak for those who historically have gone unheard. Although there are exceptions, such as the Bellamy quilt, women have most often been the makers of quilts, and these objects can serve as singular documents of lives unrecorded in the written archive. In this sense, even as it encapsulates tradition, the quilt is inherently radical. By chronicling women’s lives through fabric, quilts are highly visible and enduring manifestations of otherwise buried histories—the daily experiences of women and girls so often missing from our textbooks.

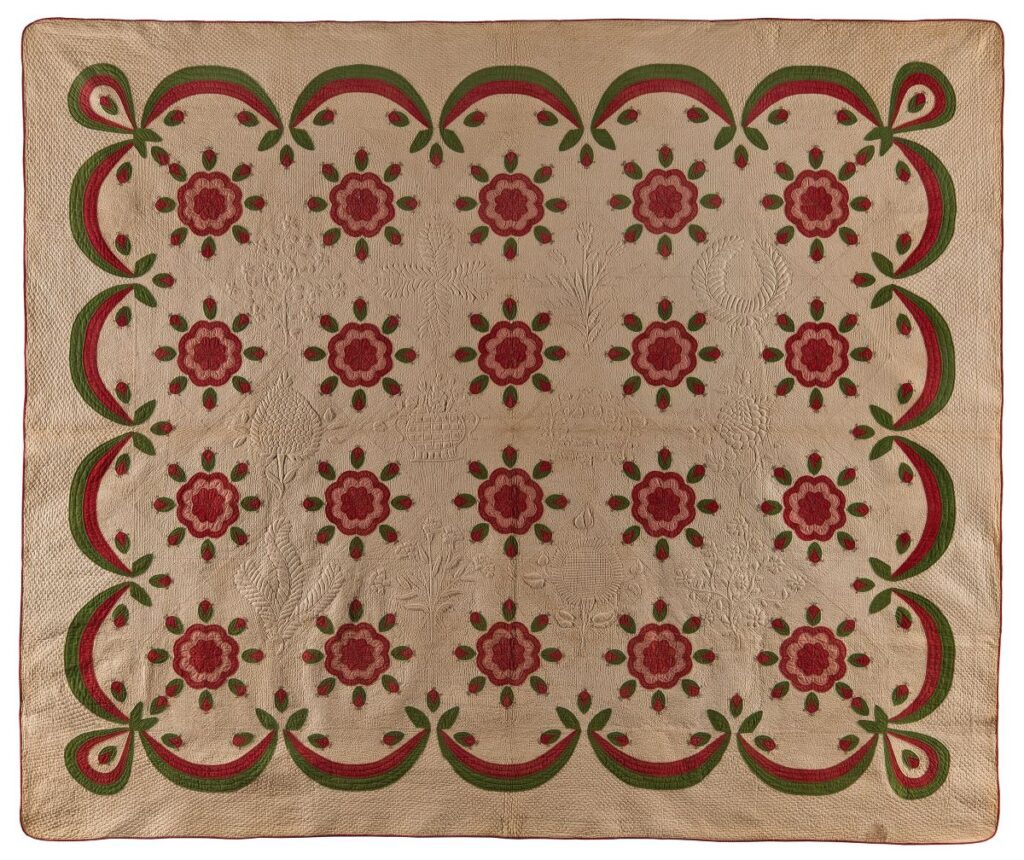

In an unusually direct acknowledgment of enslaved people’s contributions to early American craftsmanship, an old note pinned to the back of a nineteenth-century Kentucky quilt chronicles its history. Although the quilt might otherwise have been assumed to be the project of a wealthy white planter’s wife, in fact, enslaved women in the household made it. The possible makers have been identified as Ellen Morton Littlejohn and her sister Margaret (Fig. 3).

Although little is documented about the sisters’ experiences, family histories recall Ellen Littlejohn as a seamstress and Margaret Morton Bibb as a cook. Their mother, Eve, cared for the plantation owners’ children. Together the three women lived alongside at least thirteen other enslaved members of their Kentucky plantation household.

What That Quilt Knows About Me is on view at the American Folk Art Museum through October 29.

EMELIE GEVALT is the Curatorial Chair for Collections and Curator of Folk Art at the American Folk Art Museum.

SADÉ AYORINDE is the Warren Family Assistant Curator at the American Folk Art Museum.