On August 18, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution was ratified, granting women the right to vote in political elections. The road to suffrage had been a long one. The fight began in the late 1840s in New York at the Seneca Falls Convention, the first nationally prominent gathering held in support of women’s rights. At the time, women’s suffrage was thought too radical even by many attendees, but the group ultimately agreed to pass a resolution to pursue a woman’s right to vote. Some would argue that this fight for equality is still not finished, and in 2019 and 2020 we mark the centennial of these historic occasions with events and celebrations by a host of museums and other institutions created to remind us of how far we’ve come, and the importance of protecting these achievements.

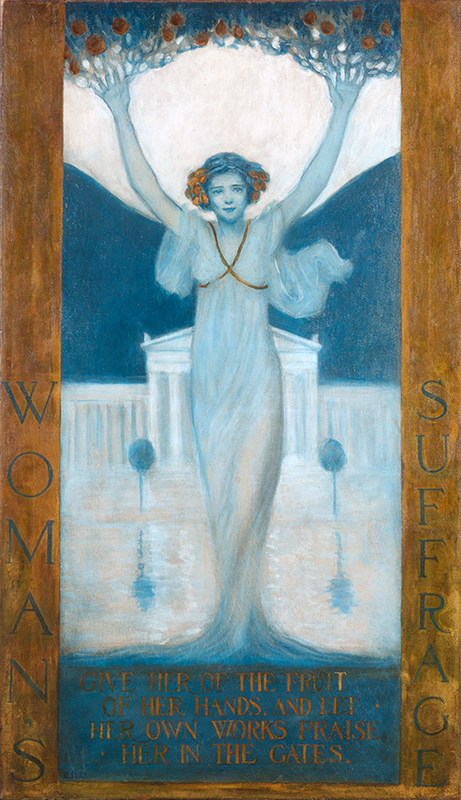

The National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC, is participating in the festivities with Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence. The exhibition spans the entire movement, organized chronologically as well as thematically, focusing on topics such as militancy, compelling tactics, and the legacy women have left behind. Visitors will see portraits of the movement’s pioneers—Susan B. Anthony, Sojourner Truth, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton—as well as of other important activists, such as the first woman to run for president, Victoria Woodhull; and Alice Paul, who organized the first-ever march on Washington’s National Mall in 1913. The National Portrait Gallery tells these women’s stories through ballots, fliers, banners, and videos.

Pockets, aprons, and housedresses from colonial America to the 1990s are on view at the National Museum of American History, also in Washington, in the exhibition All Work, No Pay: A History of Women’s Invisible Labor. The show examines the role of women in American society as caretakers, rearers of children, and homemakers—the “unpaid labor” that is expected of women, but should not be the responsibility of them alone. While acknowledging the steps forward America has taken, the museum also reflects on what could be improved on.

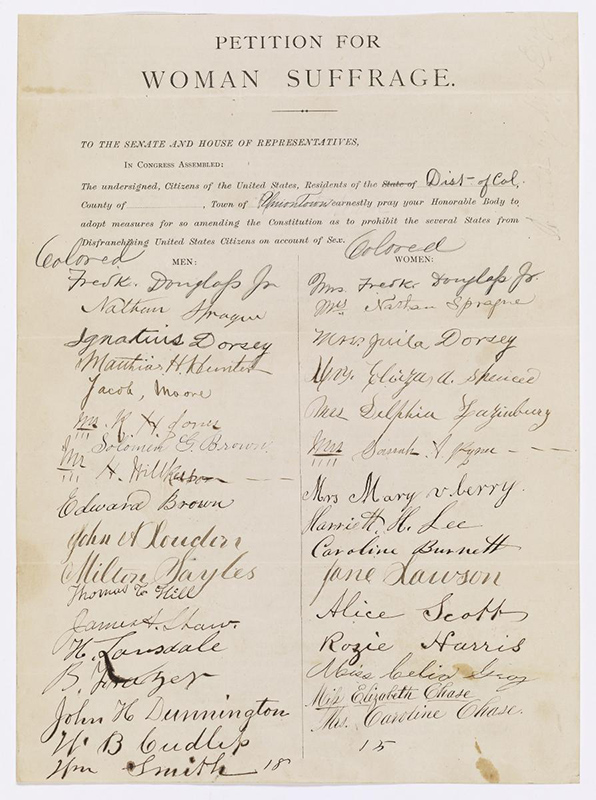

Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote, on view at DC’s National Archives Museum, showcases historical documents chronicling the timeline of the suffrage movement. These include an 1865 letter from Stanton, Anthony, and abolitionist Lucy Stone, urging friends to send petitions supporting women’s suffrage to their representatives in Congress. Also on view is the petition that was approved by the House of Representatives and the Senate to include the Nineteenth Amendment in the Constitution, dated June 4, 1919.

The Library of Congress will exhibit organizational and personal papers from groups such as the National Woman’s Party and the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), as well as of leaders of the movement such as Mary Church Terrell, one of the first African-American women to earn a college degree, and two-term president of the NAWSA Carrie Chapman Catt. Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote traces the suffragists’ path from the Seneca Falls Convention to modern day. This exhibition is one of many celebratory exhibitions in the library’s yearlong initiative, Explore America’s Changemakers.

Smaller cultural institutions nationwide are also celebrating women’s empowerment. For example: Ashland, the Henry Clay estate in Lexington, Kentucky, is hosting a special tour of the house and grounds that highlights the lives of nine women from Ashland’s history and how their roles and status evolved over time.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton famously said, “Come, come, my conservative friend, wipe the dew off your spectacles, and see that the world is moving.” Anyone who shares this sentiment will appreciate these thought-provoking exhibitions. For more information about centennial exhibitions in your area, visit 2020centennial.org.

— Katherine Lanza

Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence • National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC • to January 5, 2020 • npg.si.edu

All Work, No Pay: A History of Women’s Invisible Labor • National Museum of American History, Washington, DC • to December 31, 2020 • americanhistory.si.edu

Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote • National Archives Museum, Washington, DC • to January 3, 2021 • museum.archives.gov

Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight for the Vote • Library of Congress, Washington, DC • to September 2020 • loc.gov