In 2005 the Maine auction house F. O. Bailey Antiquarians offered a late eighteenth-century oil portrait of Nancy Bezoil Lane and her daughter Betsy as a painting “in the manner of Joseph Badger.” Marvin Sadik—by then an art dealer, but formerly the director of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC—bought it with a winning bid of $32,480. He had recognized the portrait as the work of the Salem, Massachusetts, artist Benjamin Blyth, an attribution based on the painting’s subject, its composition, its characteristic handling of anatomical elements, and its palette. Sadik’s coup ranks as one of the most notable discoveries of a Blyth oil portrait.

Blyth has been best known for his pastels, which he drew from the mid-1760s until about 1782 or 1783. His pastels of John and Abigail Adams, made soon after their marriage, are iconic images in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society. Blyth made pastel portraits of a cross-section of people from Salem and other Essex County towns, among them William Goddard, who established the system of mail delivery that evolved into the United States Post Office, and members of the family of the shipping magnate Elias Hasket Derby, known as America’s first millionaire. Several Blyth pastels, such as that of the physician Joseph Lemmon, now in the Smithsonian American Art Museum, were once thought to be the work of John Singleton Copley.

Blyth also executed portraits in oil, but many have long been either misattributed, or attributed to an “unknown artist.” This is not surprising. There is little documentation for Blyth’s work as an artist in any medium, beyond advertisements, one bill for payment due, and several diary entries by sitters. As his portraits passed through generations of owners, or out of the sitters’ families entirely, the name Blyth became unfamiliar—as did, quite often, the names of his subjects. As well, museum staffs have not had the time to research their collections. For example, Blyth’s oil portraits of Benjamin Moses, and of his wife, Sarah, with their child Betsy, were not—despite being signed and dated—identified as his work in the 1936 Catalogue of Portraits in the Essex Institute (now part of the Peabody Essex Museum). It took the rare, astute scholar Nina Fletcher Little to recognize the historical value of the Moses portraits and acknowledge Blyth as the artist.

I have spent four years researching Blyth’s work and its stylistic hallmarks while working on the manuscript for a book. Along with pastels and artwork Blyth made as the basis for prints and engravings, I believe I have newly identified six more oil portraits by him, bringing the total of such works attributed to this important American Revolutionary War–era artist to thirteen.

The earliest known oil portrait already attributed to Blyth is that of Dr. Ezekiel Hersey, a founder of Harvard Medical School. The portrait now hangs in the dean’s office there. In an early Blyth effort at oil portraiture, painted around 1769, the rendering of Hersey’s face is awkward, with too prominent, heavily drawn eyes. His lace cuff and silver snuffbox, however, are beautifully depicted.

A portrait of the evangelical minister George Whitefield, a founder of Methodism, now in the collection of the Congregational Library and Archives in Boston, has long been attributed to Blyth and is believed to have been painted in 1770, when Whitefield last visited Salem, or as a commemorative portrait made after Whitefield’s death later that year. The portrait is based on an engraving of Whitefield made by John Greenwood after a painting by Nathaniel Hone done in the mid-1760s. Although badly crackled, the painting serves as a good guide for studying Blyth’s oil technique.

Blyth seems to have painted no oils during the next few years. He was active among the troops during the Revolutionary War, and was also the agent for a privateer harassing British ships. While on frequent travels he could have easily carried his pastel crayons, but it is unlikely he would have brought along the cumbersome paraphernalia needed for oil portraits.

Blyth was back in Salem by 1779, and portraits in oil became the norm for him. A portrait of sea captain Edward Allen painted about 1780 and now in the collection of the Peabody Essex and for many years unattributed, is likely his work. Allen had ties to the family of Elias Derby, patrons of Blyth. The wife of Allen’s namesake son, Edward, was a daughter of Lydia Phippen Fisk and Thomas Fisk, both of whom were subjects in pastels by the artist. After Allen’s death in 1816, his close friend the prominent Salem minister William Bentley asked the family to give him Allen’s portrait, and he took it away. But as he wrote in his diary: “In the evening it was reclaimed by the daughters. . . . I had cut it down to separate the injuried [sic] parts but must return it.”* At some time, Allen’s portrait underwent conservation, during which numerous areas were overpainted, which makes positive analysis of Blyth’s style difficult. Nonetheless, its general handling and date suggest Blyth’s hand. Although it probably will never be known since Bentley took it upon himself to cut down the painting, the color background seems to hint at a bust-only portrait.

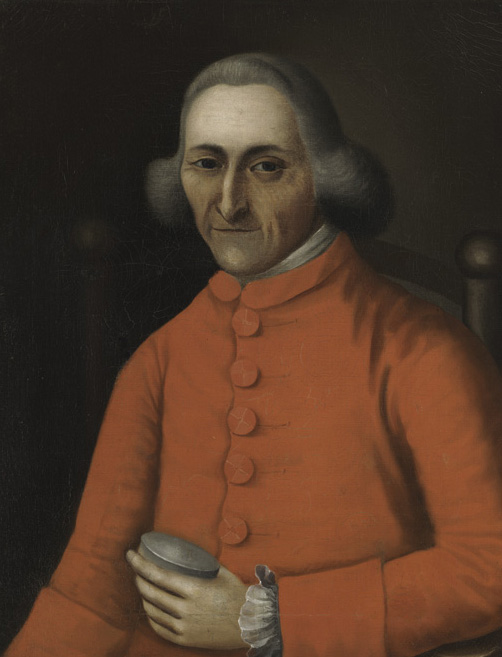

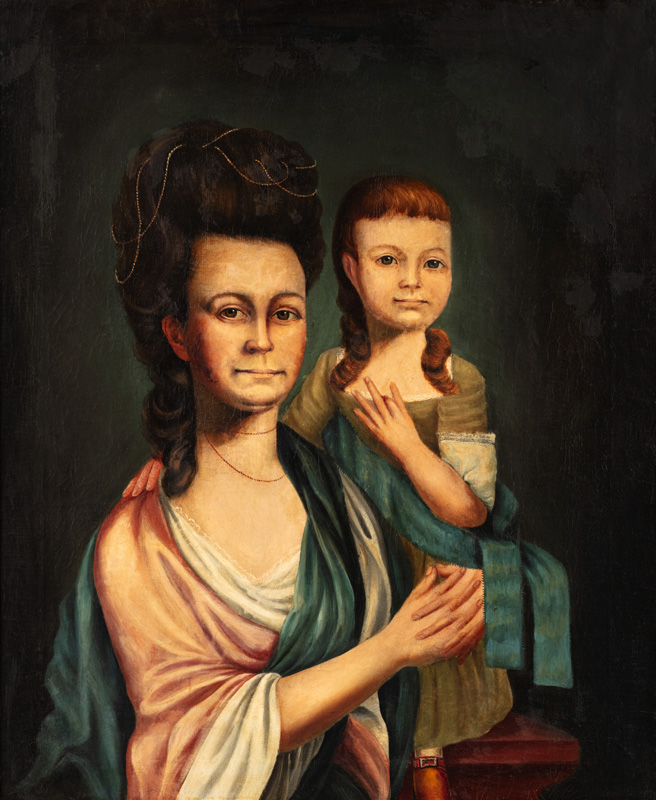

The double portrait of Nancy Lane and daughter Betsy offers perhaps the best reference point for judging the stylistic features of artwork by Blyth. Betsy, the sixth of the Lanes’ eleven children, was born in Salem in 1781, so the portrait can reasonably be dated to 1782 or ’83. The composition—a mother holding a small, standing child on her lap, both full-face—is identical to that of a likeness of Sarah Moses and her baby, also dated about 1782. The rattle held by Betsy Lane is the same as those in at least four pastels of children believed to have been done by Blyth around the same time. The Lane portrait has not suffered much, if any, damage like the overall crackling of the Whitefield, or the blurring that resulted from the restoration and repainting of the Allen portrait and that of Benjamin Moses. Fortunately, an undated photograph of the Benjamin Moses portrait in the Frick Art Reference Library preserves the better rendering of his face before it underwent the repainting.

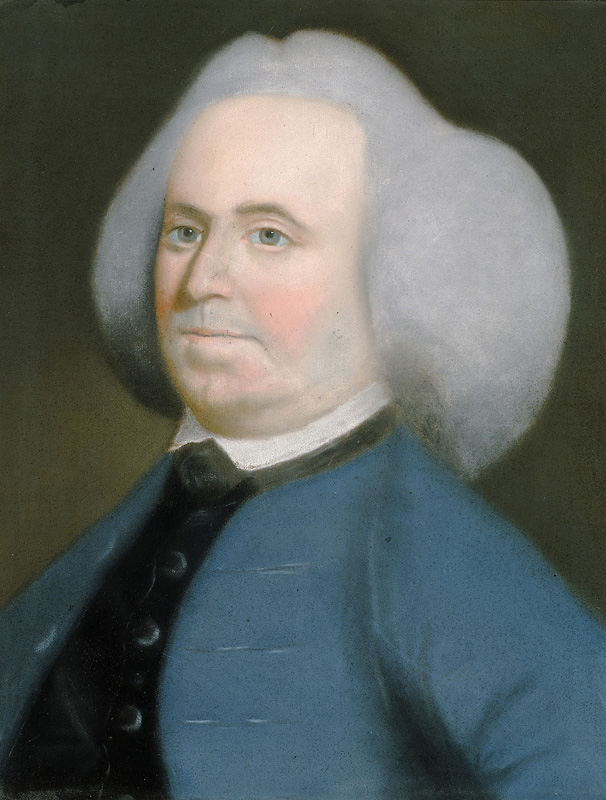

The same mother-and-child format of the Lane and Moses portraits was used for another previously unattributed painting in the Peabody Essex Museum, depicting Sarah Northey King and her child Ann, born in 1778. There are signs of later overpainting of this portrait, primarily in brown strokes, some quite broad, that cover a portion of Sarah’s hair and pearls, and outline the crease in her chin. The same observations may be made for the companion portrait of Benjamin King. The face and right ear display touches of red paint that look added. The brass of the telescope held by King, which is untouched, shows that Blyth could depict metals very well, as he did the silver snuffbox held by Ezekiel Hersey. Both the format and execution of the King portraits, including the way their personalities are rendered, bespeak Blyth.

Blyth joined the Masons in 1781, and some of his lodge fellows and members of their families became his subjects. One, I believe, was Revolutionary War hero Stephen Abbot (1749–1813), a leader of St. Peter’s Church in Salem, the congregation to which the Blyth family belonged. A portrait of Abbot in a private collection was destroyed in the great Salem fire of 1914. A photograph of the painting is shown in Harriet Silvester Tapley’s book St. Peter’s Church in Salem, Massachusetts, Before the Revolution, published by the Essex Institute in 1944. In it, the portrait is described simply as “American School.” To my eye, clearly it was by Blyth.

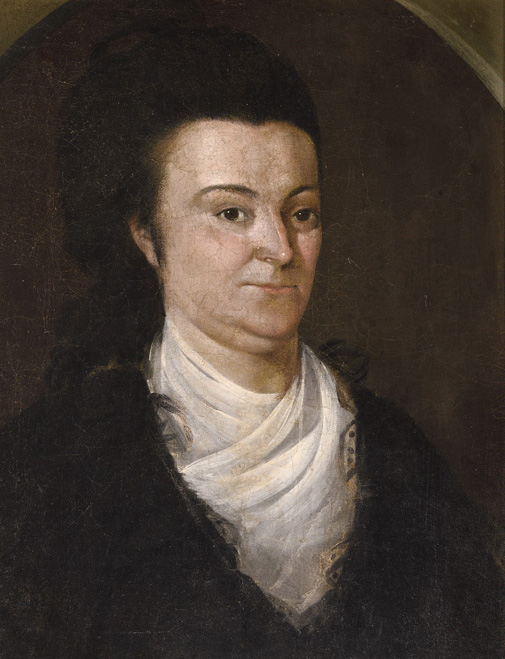

A bust portrait of Deborah Prince Cary, second wife of Newburyport, Massachusetts, minister Thomas Cary, painted around 1782, is one of Blyth’s most successful works in oil. It shows much better handling of the medium. The facial modeling is also much improved over that seen in the Hersey portrait. The portrait depicts a serious-mind-ed woman exuding a sense of responsibility. Mrs. Cary is severely dressed in black, and a white scarf covers her front. Unlike many of Blyth’s portraits, this one has been well cared for and still has its original frame and hanging hooks, a credit to the First Religious Society of Newburyport, which owns it.

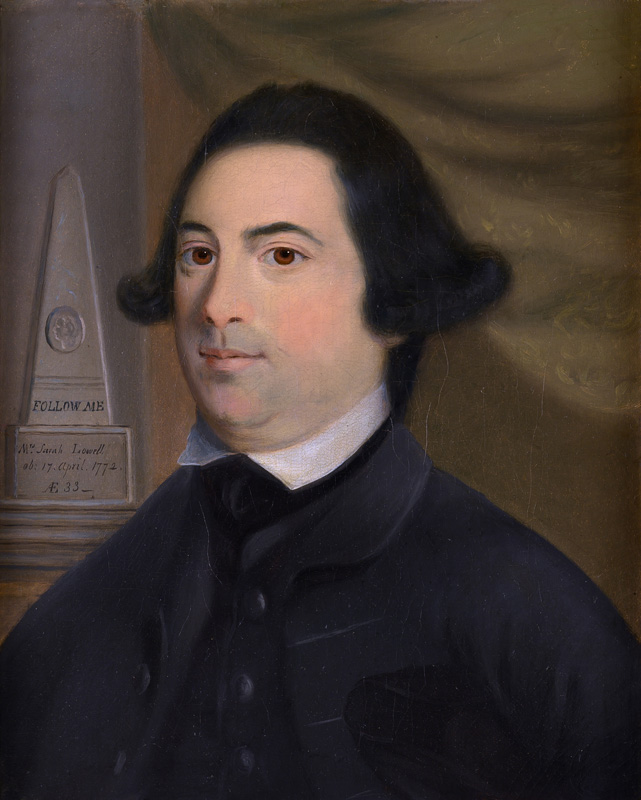

A portrait of John Lowell was offered in a sale by Christie, Manson and Woods in New York on April 24, 1981, and was attributed to “Benjamin Blythe.” The painting carried a disclaimer on authenticity for good reason: its composition is not typical of Blyth. It looks much more like one of his pastels, and it also is a highly unusual depiction for him, with an obelisk in the background memorializing the death of Lowell’s wife, Sarah. The style of the portrait, however, indicates Blyth, although it, too, shows signs of repainting.

For more than a century, conflicting information in Essex Institute catalogues complicated the discovery of the identity of the artist who made a winsome portrait in its collection known as Boy with Dog. I believe it was painted by Blyth. The work was donated to the Essex Institute in 1908 by a Mrs. Henry R. Luscomb, which suggests to me that the lad is likely William Luscomb, who was baptized at St. Peter’s Church in 1765. He is dressed fashionably, with the wide lace-edged gossamer collar worn by young boys from well-off families in the late 1770s. William’s adoring pet dog is seemingly hairless—the manner in which Blyth typically depicted cats and dogs. The pet’s collar has the engaging inscription: “I am Wm [worn away]’s dog. Whose Dog are you?”—a play on a couplet by Alexander Pope: “I am His Highness’s dog at Kew/ Pray tell me, Sir, whose dog are you?”

Benjamin Blyth was probably indebted for inspiration to Joseph Blackburn, the British-born portraitist who enjoyed great patronage in Massachusetts in early America. Blyth could well have studied his paintings in Salem households at the time, and he did make a copy in pastels of Blackburn’s oil painting of Jonathan Simpson for a Mrs. Holyoke, Simpson’s granddaughter. Like those of Blackburn, the portraits by Benjamin Blyth are unabashed character portrayals of people with no attempt at flattery. They are an important legacy of the era.

BETTINA NORTON is the former museum registrar and de-facto curator of prints at the Essex Institute and editor emerita of the Boston Musical Intelligencer. She welcomes correspondence about Benjamin Blyth at toninorton1@gmail.com.