On September 29, 1760, a school for enslaved and free Black children opened in Williamsburg, Virginia. The school was the result of an educational initiative begun decades earlier in Great Britain by the Reverend Dr. Thomas Bray and his associates, who sought to establish multiple schools for individuals of African descent in British North America. Their aim was to convert Black attendees to Christianity while educating them and instilling notions of obedience.

The Reverend Thomas Dawson and printer William Hunter of Williamsburg worked to launch the city’s school, securing both a location and a teacher. This became the most successful “Bray School” in Virginia. A single teacher, Ann Wager, would instruct an estimated four hundred enslaved and free Black children there between 1760 and 1774, when the school closed.

The Williamsburg Bray School’s first location was across the street from a large carpenter’s yard near the College of William and Mary. Bray School trustee Robert Carter Nicholas wrote to London that the school remained in the rented building “as long as it was tenantable.” Some have assumed that it was in disrepair since it served for only five years before the school moved to a new location in 1765.

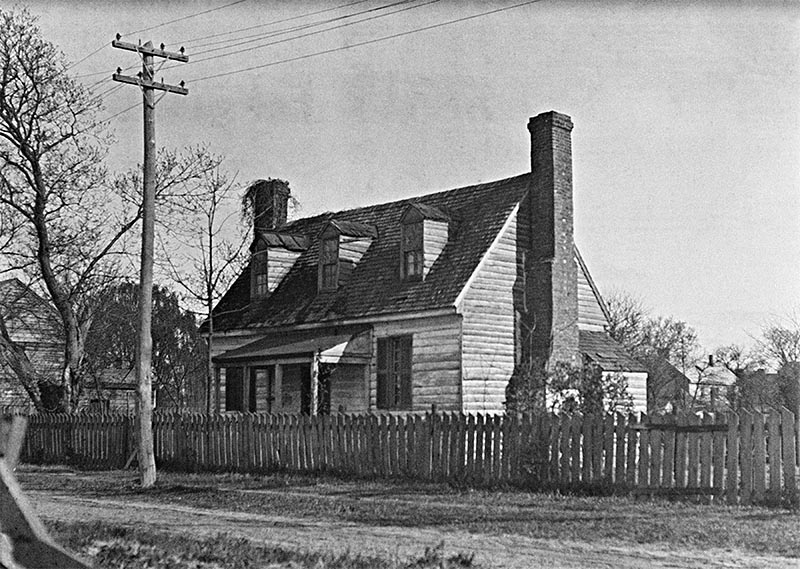

What became of the first Bray School building? By 1926 a small frame house stood on the site where the Bray School was thought to have operated. The structure had seen multiple changes and additions, and was then a women’s dormitory for students at William and Mary. To make way for a new residence hall, the structure and its additions were moved a block away in 1930. Decades later, extensive research by William and Mary professor Terry Meyers confirmed that the Bray School was first operated on the site now occupied by the dormitory built in the 1930s, suggesting that the small, relocated house might be the first Bray School. So, over several years, researchers, architectural historians, and material analysts sought to determine if the building contained the remnants of the school.

Architectural historians believed the heavily altered building might date anywhere from themed-eighteenth century to the early nineteenth. Dendrochronology, the scientific method of dating tree rings, was attempted on exposed framing in the attic, but the fast-grown lumber found there could not be dated. (Fast growth occurs when optimal regional environmental conditions cause trees to grow unusually quickly.) Moreover, fast-grown lumber is typically seen in construction toward the end of the eighteenth century in Williamsburg, well after the Bray School closed. And the few early paint layers that could be found in the structure contained components first used in the early nineteenth century. The house was beginning to look like a later structure based on the physical evidence.

In 2020 Colonial Williamsburg’s Department of Architectural Preservation and Research was asked to look at the house and determine if there were any further ways to discover a date. As a result, in concert with our associates at William and Mary, we opened select areas of the wall, exposing principal framing members for further dendrochronological analysis. Working with the Oxford Tree-Ring Laboratory, new samples were taken. Four of them could be dated with high confidence and three of those were intact enough to give specific felling dates and seasons. The study showed that the trees used to construct the frame were felled in the winter of 1759–1760 and the spring of 1760. This gave concrete evidence that the small building was, in fact, the Bray School, and thus the earliest surviving building in the United States dedicated to Black education. Our understanding of the building is just beginning. There are several years of research, preservation, and interpretive work ahead. This story, once hidden in plain sight, can now begin to be told.

MATTHEW WEBSTER is the executive director of the Grainger Department of Architectural Preservation and Research at Colonial Williamsburg.