In 2018 I published an article about my discovery of three miniatures of John Hancock and his two children who died young (Figs. 1–3). The children’s miniatures were placed together at a later date in the elegant gold, double-sided, blue and white enameled case designed to be worn as a piece of mourning jewelry. Portrait miniatures are commonly studied, but their cases rarely are. In this instance, a little case tells a big story.

Speculation about a possible maker led me to look for clues in Hancock family papers and inventories where I came upon the name “Twycross of London” associated with jewelry and timepieces purchased by the family. A search for the name “Stephen Twycross” directed me to the 1987 article in The Magazine ANTIQUES by Martha Gandy Fales, “Federal Bostonians and their London Jeweler, Stephen Twycross.” This article, and a similar one by Fales published in Jewellery Studies ten years later, are all that has been written about Twycross. Without her article as a point of departure, my research would probably have gone nowhere.

Fales discussed several prominent Boston families of the Federal period––the Barrells, Daweses, and Salisburys––and the pieces owned by these families that are documented as by, or attributed to, Twycross’s London shop, and all dating between 1786 and 1818. It is rare to have a record of a particular maker and his clients in the Georgian period when jewelry was not customarily signed. Fales’s work established a baseline for attributing works to Twycross. She noted distinctive “Twycrossian” jewelry features, chiefly gold with bands of blue enamel, often encircled by pearls. His works sometimes came in a white satin-lined red leather box with his paper trade label. The children’s case and several other Hancock family pieces fit this description. Most significantly, they owned a brooch with its original case labeled “S. Twycross.” My research augments Fales’s by introducing the Hancocks as newly discovered clients, by investigating the connections between Twycross and the American families, and by recording new examples of his work, making it possible to further define characteristics of it which might prove useful in identifying new pieces and new owners.

An important finding of my research is that the Federal Bostonians’ choice of this particular London jeweler was far from random––Stephen Twycross and his family had strong ties to America and to many of the elite families of Boston––through his mother Lizey Deblois’s side of the family living in Boston and through his brother Robert, an officer in the Royal Navy who went to America and established a family there.

Stephen Twycross (1746–1812) was born to the Rev. Robert Twycross, a Vicar in Oxfordshire, and his wife Lizey Deblois, the daughter of Huguenot refugees. Stephen and his older brother Joseph were both apprenticed to goldsmiths. This might have been because of their Huguenot ancestry. The French jewelry industry lost most of its best craftsmen, particularly goldsmiths, when Louis XIV revoked the Edict of Nantes in 1685, causing an emigration of Protestant Huguenots to England, Holland, Germany, and America.

Stephen was apprenticed to Thomas Millington who specialized in intricate work in precious metals with elaborate decoration such as found on miniature cases and watches. The art of painting in enamel on watchcases and dials originated in France, and many of the goldsmiths who specialized in this were from the town of Blois. Given their name, it is possible the Deblois family had roots in Blois.

Stephen married in 1770 and had five children. He obtained his freedom in 1772 and established himself as a manufacturing jeweler in the Holborn district of London, the heart of the jewelry trade, bordering Clerkenwell, the watchmaking district, also known for producing optical instruments. By 1793 Twycross was a member of the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths. He was also making clocks and watches as well as jewelry, and he seems to have worked on navigational instruments such as sextants, octants, and compasses. Even though he did not sign his jewelry, Stephen did sign several instruments and timepieces.

Stephen’s eldest son Robert (1773-1821) became his father’s apprentice and joined him in the firm around 1800. They also had a clockmaking facility at 8 Haymarket from about 1800 to 1804, while their main jewelry workshop was at Newcastle Street, Strand from 1796.

Stephen’s son Stephen (1779-1828), who apparently did not follow his father’s trade, went to America around 1797 where he was acquainted with the Hancock family in Boston and became a naturalized citizen in 1799. Later, he moved on to Cape Town, South Africa.

Stephen’s brother Lt. Robert Twycross (1747–1783) joined the Royal Navy in 1762 but moved to America to be the captain of a merchant ship transporting cargo along the coast, working at times with his cousins Gilbert (1725-1791) and Lewis (1727–1799) Deblois of Boston. In 1764 he married Lydia Goodwin (1742–1812), the daughter of Major Samuel Goodwin (1716–1802), the agent for a land company, the Kennebec Proprietors. He was charged with promoting and administrating settlement of an area of some three thousand square miles in the District of Maine, then part of Massachusetts. John Hancock’s uncle Thomas (1703–1764), who had adopted him and made him his heir after his father died, was a major partner and willed a great deal of land to his nephew John. In 1761 Major Goodwin moved his family from Charlestown to Pownalborough (now known as Dresden) and built a mansion on the banks of the Kennebec River. In addition to serving as the Goodwin’s home, the building housed the Pownalborough Courthouse, an inn, tavern, post office, livery-stable, fencing hall, dance hall, church, and meeting house. Goodwin descendants lived in the house into the 1930s. The local historical society purchased the property in 1954. John Hancock’s cousin, Judge Jonathan Bowman (1735–1804), also built a mansion in Pownalborough in 1762 and later married, as his second wife, Ann Goodwin (1765-1856), Robert and Lydia Twycross’s niece.

Robert, Lydia and their four sons lived on their farm near her family compound. With the American Revolution on the horizon, divisions between Loyalists and Patriots were intensified in many families––including the Goodwins and Twycrosses. In 1776 the Twycross home was burnt to the ground with all they possessed destroyed, presumably because they were Loyalists. In 1778 Robert returned to the Royal Navy and fought in the West Indies in the conflict known as the Anglo-French War (1778 to 1783). He was severely wounded in battle in 1780 and was given shore duty in charge of a “Rendezvous.” (The Impress Service, or press-gangs who coerced men into joining the navy, called the places they gathered in all major ports “rendezvous.”)

Gravely ill, Robert wrote to Lydia asking her to join him in England with the children. In February 1782 Lydia petitioned the Massachusetts Legislature for permission to go and return. Lydia, her children, and a “Cousin Deblois” arrived in London and were met by her husband Robert and his brother Stephen. In early 1783 she wrote to her sister in America about Stephen and his family: “They live vastly genteel and are very prosperous and have a fine fortune.”

When Robert died on April 21, 1783, Lydia went home to Maine with three of her sons, who grew up in Pownalborough and “followed the sea.” She left her eldest son, fourteen-year-old Robert Harcourt Twycross (1769-1855), in England to be his uncle Stephen’s apprentice. He eventually went into business for himself, probably using his middle name to distinguish himself from his cousin Robert, Stephen’s son. He sent a miniature of himself to his mother in a case with his label. There is another miniature said to be of him, but the provenance is uncertain and there is no case. One piece of Robert’s jewelry is known.

By 1803 Robert Harcourt was in serious financial trouble because of the deteriorating international situation––Britain declared war on France in 1803 and would remain at war for over a decade, and America became engulfed in the conflict as well. He and his American brother Stephen Nymphas Twycross (1773–1841), a ship’s captain, planned a business venture together––to send goods from the manufactories in London to sell in Boston––but there is no indication this came to fruition or that Robert ever sold jewelry in Boston. In 1804 he went bankrupt, and again in 1809. By 1814 he was no longer a jeweler but was listed as a pearl and diamond broker at 9 Thavies-inn, Holborn. Robert seems not to have had anything to do with his uncle Stephen’s business in Boston, but possibly supplied pearls and diamonds for his jewelry.

His mother, Lydia Goodwin Twycross, became the responsibility of both the Twycross and Deblois families. After her husband died, she applied for his Royal Navy pension but there were continuous difficulties collecting it. She constantly relied upon her sons, her brother-in-law Stephen in England, George Deblois (1750-1819), and Gilbert Deblois, Jr. (1755-1808), the children of her husband’s Boston cousins, for help.

The first of the Deblois family to arrive in America in 1720 was Stephen Twycross’s uncle, Stephen Deblois (1699–1778), who came in the retinue of the New York Royal Governor. Other Deblois family members followed, forming a successful trading cartel that stretched from New York, Newport, Boston, Salem, and on to Halifax.

Stephen Deblois settled in Boston and, with his two sons Gilbert and Lewis, imported hardware and other goods, including musical instruments. They were talented musicians who were church organists for King’s Chapel in Boston. In 1754 the Deblois family built the first concert hall in the city; their shop was on the first floor with the concert room on the second. This room was also used for meetings of the Masons and other community groups. In 1749 Gilbert married Ann Coffin (1730-1808) and had sixteen children. His brother Lewis married twice and had four children. Through marriages, business ventures, cultural activities, religious and civic affairs, the Deblois family became tightly entwined in the fabric of life in Boston and beyond.

However, the Revolution divided many families, the Debloises among them. Loyalist family members often moved to England while those supporting the Revolution stayed. Gilbert and Lewis were Loyalists who left Boston with the British army in 1776. Gilbert took three of his sons with him, leaving his wife and the other children behind. In 1778 Gilbert was proscribed and banished by the State of Massachusetts, and his property was confiscated. He died in England in 1791 and was buried at Pentonville (near Holborn) beside his “uncle Twycross” and “sister Winslow.” These were probably his uncle the Rev. Robert Twycross who died in 1789 and his brother Lewis’s sister-in-law, Jemima Debuke Winslow (1732-1790), wife of Isaac Winslow (1709-1777). Robert Harcourt Twycross lived in Pentonville as well. Lewis also died in England in 1799. The Gentleman’s Magazine reported his death: “Very suddenly at his apartment in Holborn, after being out on that day, Mr. Lewis Deblois, late merchant in Boston, North America.”

After the Revolution, several of Lewis and Gilbert’s sons lived and did business in America. Lewis’s son, George Deblois (1750–1819), who had spent the war in Nova Scotia, returned to Boston about 1789 and began importing dry goods. Gilbert’s sons Gilbert, Jr. (1755-1808) and William (1758-1806), who had remained in America with their mother, were merchants in Boston. Their brother Stephen (1764–1850) returned to Boston from London to do business and married Elizabeth Amory (1768–1850), his first cousin, in 1792. Gilbert, Jr. was allowed to buy back two-thirds of the confiscated land and the warehouse––and his mother regained the family home. They all imported items from England, frequently on Capt. James Scott’s ships, the Neptune and Minerva. After the war, Gilbert senior made several trips back to Boston to attend to family affairs, sailing with Capt. James Scott at least once.

Captain James Scott (1746–1809), was a key figure for Twycross and Deblois connections in America. He was the long-time ship captain for Thomas Hancock beginning about 1764, then for his nephew and heir, John Hancock. Scott remained in England during the Revolutionary War. At the peace, John Hancock wrote to Scott, inviting him to join him and return to trade. Now a widower with three children, he moved his family to Boston where he and his son became naturalized American citizens in 1789. He resumed his twice-a-year trips between London and Boston––carrying passengers, parcels, cargo, and undoubtedly letters––for such merchants as the Hancocks and Deblois. After John Hancock died, Scott married his widow Dorothy Hancock in 1796 and retired––after crossing the Atlantic for the 111th and last time.19 His son, Capt. James Scott, Jr. continued the twice-yearly voyages his father once made. His daughter Elizabeth (c. 1779–1830) married John Hancock’s nephew, also named John Hancock (1774–1859), in 1799.

After the Revolution, Boston merchants, whose commerce had been restricted as colonials, now participated freely in world trade. A new elite was developing out of the “Tradesmen, Mechanics, and Manufacturers of this town and vicinity” who had supported the Revolution.20 The Bostonians Fales wrote about were members of this merchant aristocracy. They had been the purveyors of necessary goods for the Continental army such as groceries, hardware, dry goods, and bread.

They began importing great quantities of British goods again. While New Englanders typically followed English fashions, imported articles had to be suitable for a Puritan Bostonian. For example, when John Hancock ordered a “chariot” from England in 1783 it was to be “elegantly neat not made expensive by external Tawdry Ornamentation.” A luxury item such as jewelry had to have a moral purpose or serve a practical use in order to permit its acquisition. Rings, bracelets, brooches, earrings, and necklaces could be possessed as long as they could be classified as mourning jewelry, while watches and chatelaines were acceptable because they were utilitarian. This is the period when Stephen Twycross was jeweler to the Federal Bostonians that Fales wrote about.

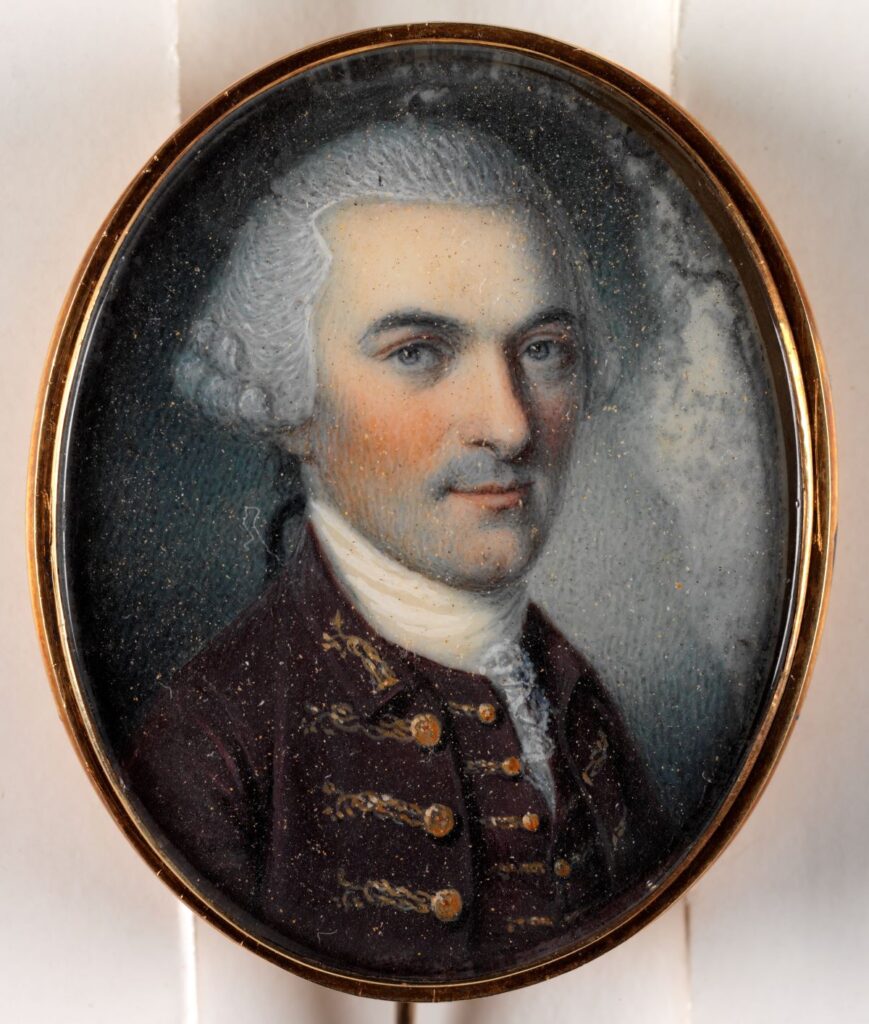

How the lives of the Federal Bostonians and Stephen Twycross were woven together is illuminated further by adding the Hancock family as patrons. During the American Revolution, English cases were not available, so in 1776, when John Hancock commissioned portrait miniatures of himself (Fig. 1) and his new bride, Dorothy Quincy (unlocated), from Charles Willson Peale, the artist probably fitted them into cases he made, as he was believed to do. His portrait of the Hancocks’ nine-month-old daughter Lydia, who died in 1777, was probably originally housed in a Peale case as well (Fig. 2). She was named for John Hancock’s beloved Aunt Lydia Henchman Hancock, wife of Thomas Hancock. The Hancocks’ son, John George Washington Hancock, was born in May 1778. Tragically, young Johnny died on January 27, 1787, from a head injury suffered in an ice-skating accident. His portrait was possibly painted by Joseph Dunkerley (Fig. 3).

The year 1787 is therefore the earliest possible date for the case for the miniatures of the two children, but purchasing such sumptuous mourning jewelry would not have been expedient for John Hancock, who was still involved in politics. Times were economically severe and he had to set a frugal example. In the boy’s obituary, it was written of Hancock: “[t]his Hon. Gentleman hath set an example, in his strict observance of the regulations of the town respecting funerals, which we wish may be followed by every class of people among us. He hath guarded against every unnecessary expense for himself and family, in the article of mourning.” On the same page was news of Shays’ Rebellion (August 1786-February 1787), an armed, popular uprising in western Massachusetts sparked by high taxes and harsh economic conditions.

After Johnny’s death, Hancock was elected governor again and won reelection every year until he died in office on October 8, 1793. By the time John Hancock died, mourning jewelry was acceptable again and the family ordered it from England through Captain Scott. In November 1793, shortly after Hancock’s death in October, Dorothy Hancock’s nephew Thomas Hancock wrote a letter on her behalf to Captain Scott with additional information to be added to an order she had given him for mourning jewelry.

A bracelet was to have John Hancock’s death date and age engraved on it as well as his Aunt Lydia’s information and a ring was to have “Johnny’s Age &c.” on the outside and “her little daughter’s age, &c.” on the inside.

The ring is unlocated but there are two “Twycrossian” bracelet clasps in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, one of which bears an inscription with both Hancock and Aunt Lydia’s dates as described in the letter; the other memorializes young Johnny. They are the same size and undoubtedly were meant to be a pair since the fashion at the time was to wear a bracelet on each wrist. The clasps, and a matching pin, also dedicated to Johnny, were gifts to the museum from the Hancock family.

Crucially, there is another piece of Hancock mourning jewelry––a brooch that descended in the family and still retains its original white satin-lined red box labeled, “S. Twycross/ Jeweller/ No. 9 Newcastle Street/ Strand/ LONDON.” The brooch, inscribed “TO THE MEMORY OF AN AFFECTIONATE UNCLE,” is listed in a Hancock family inventory as having belonged to John Hancock’s nephew John. Fales’s article shows a similar brooch ordered directly from Twycross on Aug. 27, 1796 by Joseph Barrell, which still has its original box with label.

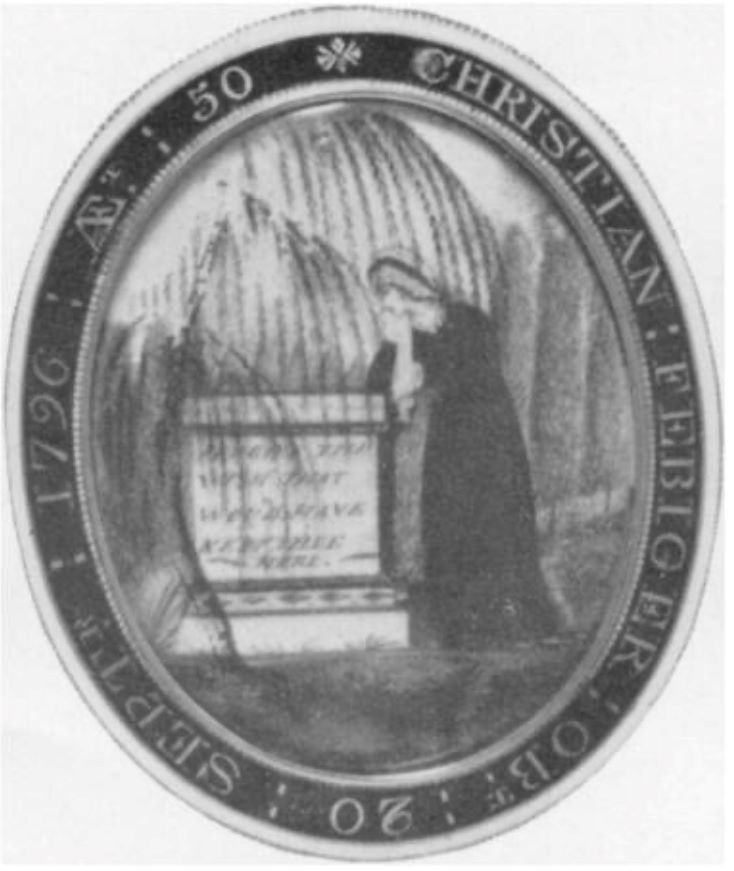

The case for the children’s miniatures was likely acquired around the same time as these pieces. To support such a date, there is a similar mourning locket recorded, but unlocated (Fig. 7). It holds a miniature by Peale of a young Hans Christian Febiger on one side, a mourning scene on the other, and is inscribed with the date of Febiger’s death, September 20, 1796.

The earliest documented direct contact between Stephen Twycross and Hancock dates to 1797. A 1917 inventory of family items includes an “Old English watch with two seals, and two cases,” along with the information that they were accompanied by a bill from Stephen Twycross dated November 18, 1797.

The Hancocks continued to purchase a variety of goods from Twycross until at least 1805, as documented by five letters from Twycross to John Hancock the nephew, one noting a first pair of pierced earrings for the latter’s little daughter, with advice on how to wear them.

These letters, written between March 1803 and March 1805, from S. Twycross & Son to John Hancock, the nephew reveal a wealth of information. An 1805 letter shows that the Hancocks were acquainted with Twycross’s son Stephen who came to America in 1797 and became a citizen in 1799. The letters also describe how Twycross shipped items to Hancock in a variety of ways–– such as with another merchant’s order or in a passenger’s care. Twycross was not only supplying custom items to select clients but selling a variety of manufactured goods and jewelry to Boston merchants for resale, probably under their own labels. One letter noted that some items had been shipped in care of “Mr Eben. Moulton where we have some plate.” Ebenezer Moulton (1768-1824) was a silversmith from a renowned family of artisans who worked in Boston from 1790 to 1820.

Twycross provided Hancock with jewelry, tumblers, clocks and watches––and he even engraved a copper printing plate for a bill of lading and a plate for a bill of exchange for him. “The plate, along with a companion plate for a bill of exchange executed in an identical style, was discovered in the 1960s “hidden between a mattress and a bedspread” in a Winthrop, Massachusetts home. Based on the plate maker’s stamps on the verso of the two plates and the engraver’s imprint on the bill of exchange plate, the two can be dated to somewhere between 1798 and 1815.”

In addition to revealing the Hancocks as Twycross clients with Captain Scott as an intermediary, my research has expanded on Stephen Twycross’s connections with the clients Fales identified in her article––the Barrells, Dawes, Salisburys, and Tuckermans. In addition, several other possibilities of how Twycross might have gained clients in Boston came to light.

Fales suggests it was Joseph Barrell (1739-1804) who purchased the earliest example of Twycross jewelry in Boston––a pair of bracelets for his wife, Sarah Webb, c. 1786 (Fig. 8). They still retain their original boxes labeled by Twycross, but there is no documentation that would confirm this early date. However, there is a 1787 advertisement in the Boston Centinel that describes a lost “Twycrossian” watch case: “Lost, at the late Fire, A WATCH-CASE, blue enamelled, with gold Stars, and a double row of Pearls. Also a HAIR TRUNK, with two drawers at the bottom, containing sheeting, &c. –– A new green Silk UMBRELLA, in a canvass case, marked E. AMORY. Any persons having the above articles in possession, are requested to leave them at Messrs. Gilbert and Lewis Deblois’s Store, Marlborough-Street, April 27, 1787.” This was likely Elizabeth Amory (1768–1850) who married her first cousin Stephen Deblois (1764–1850), son of Gilbert, in 1792.

Joseph Barrell did make the first documented Twycross purchases in America in 1796. Fales writes that it was his brother Colborn (1735–1802) in London who first put Joseph in touch with Stephen Twycross after the war. Joseph and his brothers made up a wide-ranging trading network but their loyalties were divided during the Revolution. Joseph was a Patriot who became a privateer and a contractor to the French fleet. After the war, he expanded his business as the principal investor in the ship Columbia Rediviva, the first ship to circumnavigate the globe, and the sloop Lady Washington. These vessels initiated the profitable Boston-Northwest Coast-Canton trade in 1787. On the other hand, Colborn was a Loyalist merchant and a pacifist Sandemanian elder and preacher who fled to England at the outbreak of the American Revolution, but came back to spend the war in New York, importing English goods into America for the British. After the war he returned to London. Colborn also had business connections to the Deblois and was a friend of the Winslows. On August 27, 1796, Joseph wrote to both Colborn and Stephen Twycross to order mourning jewelry, including a small brooch that still has its box with label and is similar to the one Hancock ordered.

Joseph Barrell was known as a man of wealth and taste and ordered the best for his family and his house. Some of his Twycross jewelry featured diamonds, not only pearls. Fales identified pieces having been purchased by Barrell from Twycross, and now the case that his son Joseph Barrell, Jr.’s portrait was placed in when he died in 1801 can perhaps be attributed to Twycross also (Figs. 9, 10). The case has a distinctive blue enamel back which, as we shall see, was a kind of case likely imported from Twycross and used by several miniature painters in Boston.

Another possible way Twycross first became known to Federal Bostonians is through Joseph Dunkerley (1752–1806), a miniature painter, and his brother James (1754–1820), a jeweler. Joseph painted miniatures of Barrell’s brother Theodore and Hancock’s son John George Washington, and at least three of his miniatures are housed in “Twycrossian” cases––the portraits of Elizabeth Tothill Sheppard Morris, her husband William Morris (Figs. 11, 12), and “an Early American Gentleman” (Fig. 13).

Joseph Dunkerley came to America as a British soldier during the war but deserted and joined the Americans in 1778. In 1781 he rented a house from Paul Revere, who some of his miniature cases. He later opened a shop on Newbury Street, and in 1786 he moved to a home on Winter Street, directly across the Commons from John Hancock’s mansion. His brother James, a jeweler with an expertise in mounting miniatures, joined him in Boston and opened his own business. It is possible that they both painted miniatures. In 1788 they abruptly left Boston to live in Jamaica. Their father James (1728–1802) was an enameller and jeweler in Holborn, where Twycross had his business, and from James’s will, it is known that he was on Brooks Street at the same time Robert Harcourt Twycross had his business there. In addition, associates of the Dunkerleys, Thomas Pons and John Deverell, were connected to the clockmaking and jewelry neighborhoods of London and the Deblois of Boston. John Deverell was a watchmaker from England, and when the Dunkerleys left in 1787 he hired “the person formerly employed by Mr. Dunkerley” to expand his business to include gold and silversmithing. Deverell was also a talented singer who gave concerts presented by the Musical Society in the Concert Hall built by the Deblois. He got excellent reviews. James Dunkerley left his business to Thomas Pons, a jeweler, when he left town. Pons advertised that he was the only person James Dunkerley trained in the European manner of making and repairing all kinds of jewelry work, particularly the fitting of miniatures in lockets and pins, etc.

Another possibility for how Twycross jewelry became popular with the Boston elite was through the Tuckerman family. Edward Tuckerman II (1740–1818) and his son Edward Tuckerman III (1775–1843) were related to both the Dawes and the Salisbury families who purchased Twycross jewelry. Fales discussed several pieces owned by these families. Further research now allows connections between them to be drawn.

The two rings discussed by Fales, purchased from Twycross c.1799–1800, one in memory of William Dawes, Jr. (1745–1799) and the other to celebrate Dawes’s daughter Hannah (Dawes) Goldwaithe’s (1769–1851) marriage to Daniel Newcombe (1746–1818), were likely acquired by John Lucas (?–1812), husband of William Dawes’s sister, Hannah (Dawes) Lucas (1743–1803). William Dawes, Jr. is known for having taken part in the Midnight Ride with Paul Revere to warn John Hancock and John Adams that the British were coming.

John Lucas could have learned about Twycross through his connection with the Tuckerman family. John Lucas and Edward Tuckerman II (1740–1818) were both bakers and together they purchased confiscated Loyalist estates. The records are sparse but it seems fairly certain that he is also the same John Lucas who published an intention to marry Edward’s sister Dorothy Tuckerman (1739–?) in 1759. If John Lucas married Dorothy as his first wife, before he married Hannah Dawes, this would make him not only the uncle of Hannah (Dawes) Goldthwaite Newcombe, but also the uncle of Edward Tuckerman III (1775-1843), Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury (1768-1851), and Lucretia Tuckerman Wier (1770–1797) ––all of whom are interconnected and associated with Twycross jewelry.

In 1797 the baker Edward Tuckerman’s daughter Elizabeth (1768-1851) married the merchant Stephen Salisbury (1746-1829) who was in business with his brother Samuel (1739-1818). Samuel married Elizabeth Sewall (1750-1771), Dorothy Quincy Hancock Scott’s niece, and purchased the Quincy family home in Boston. Their sister Martha (1727–1748) married Norton Quincy (1716–1801). Stephen expanded the business to Worcester where he bought property from John Hancock and built a house with a store. Stephen and Elizabeth probably met through her younger brothers Joseph and Edward. Joseph Tuckerman (1778–1840) roomed with Josiah Salisbury (1781–1826), son of Stephen’s brother Samuel, at Harvard in 1796. Both were members of the class of 1798 and remained friends. Her brother Edward Tuckerman III (1775–1843) was an apprentice in the Boston branch of S. & S. Salisbury.

Fales writes that Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury and her husband Stephen ordered Twycross jewelry from her brother Edward Tuckerman III in 1800 and 1802, as documented by several bills. There are two Tuckerman/Salisbury pieces possibly by Twycross in addition to those discussed by Fales. They lack boxes and labels, but circumstantial evidence points to Twycross as their origin. Elizabeth Tuckerman Salisbury’s sister Lucretia (1770–1797) married Robert Wier (1768–1804), a distiller and merchant in Boston, in 1790. When she died in 1797 miniaturist William Lovett (1773–1801) painted at least two portraits of her (Figs 14, 15). They were placed in brooches with distinctive backs with broad bands of translucent, dark blue enamel surrounding a glass-covered oculus containing her hair, one overlaid by her initials––a flat gold cut-out cipher. A portrait thought to be of her husband Robert, also by Lovett, is in a similar case (Figs. 16, 17).

William Lovett had previously painted miniatures of Stephen and Elizabeth Salisbury so they were probably the patrons who commissioned him to paint the miniatures to memorialize her sister. It is also possible that the Salisburys learned about Stephen Twycross from William Lovett. Apparently, they did not purchase Twycross jewelry until the 1800s.

Lovett imported cases from England in Capt. James Scott’s ship, as shown by his advertisements published in June and July 1795, which specifically mention blue enamel backs. These are likely the cases Lovett used to house Lucretia and Robert’s portraits. This type of cobalt blue enamel was invented in England in 1775––and was reserved for royalty in the beginning. Jewelry created with this enamel was often studded with diamonds. Its popularity caused it to be widely produced and less expensive versions were made with blue Bristol glass covering and highlighting patterned foil en guilloche surrounded by pearls.

Lovett also was acquainted with Gilbert Deblois’ family. His studio was near their house and he was commissioned by them to paint a copy of Copley’s portrait of Gilbert (unlocated). This special kind of case was used by several other of Lovett’s fellow miniature painters in Boston. The miniature attributed to Nathaniel Hancock of Joseph Barrell’s son, Joseph Jr., painted c.1790, was put in a similar case when he died around 1801 (See Figs. 9, 10). English miniature painters such as Henry Bone (1755-1834) used Twycross cases as well, as shown by an example that still has its red Twycross-labeled box (Fig. 18).

However, from about 1807 to 1815, the web of connections between the Federal Bostonians and their London jeweler was disrupted. France and England were at war almost continuously from 1793 to 1815: during the French Revolution, the Napoleonic Wars, and finally, the War of 1812. American merchants, although trying to remain neutral, were caught in the middle. Their ships, cargos, and sailors were often indiscriminately seized by both the English and the French. Between 1803 and 1812 the British impressed thousands of American sailors to serve in the Royal Navy––a major cause of the War of 1812. In response, President Thomas Jefferson declared a total embargo on American shipping to any port in Great Britain. However, the Embargo of 1807, which lasted until 1809, had the unintended effect of crippling American overseas trade. New England maritime and mercantile interests did not recover until after the War of 1812.

During this interim period, Robert Harcourt Twycross’s brother Capt. Stephen Nymphas Twycross (1773–1841) was prohibited from foreign trade, and in 1813 their brother Capt. Samuel Goodwin Twycross (1778–1816) was impressed by the British and languished in Chatham Prison until he was released in 1815. Earlier, in 1797, Captain James Scott’s son, Captain James Scott, Jr.’s ship was captured by the French.

Despite this, between 1805 and 1811 merchants such as Ebenezer Moulton and John McFarlane (founder of the business that became Shreve, Crump & Low), still managed to import some jewelry and watches from England. Stephen Salisbury purchased at least one “Twycrossian” mourning ring which came in the iconic red box but with jeweler John McFarland’s (1762-1820) label (Fig. 19). The ring can be dated to sometime between 1809 and 1813 when McFarlane was at the address on the label. It might have been made by Twycross and sold under the American jeweler’s label.

The Salisbury’s appear not to have acquired jewelry directly from Twycross again until 1818 when Stephen ordered a chatelaine and watch for Elizabeth’s fiftieth birthday. Chatelains were the fashionable “Swiss-army knife” accessory popular with women and men––all sorts of useful items were suspended from them, such as scissors, seals, fobs, keys, and thimbles. The gold watch was engraved “Twycross & Son, London” with a date of 1818 on the inner case.

Stephen Twycross died in 1819 and his son Robert in 1821. John Paradise took over the firm and might have continued exporting to Boston under the Twycross name, but by then the Salisburys and other Federal Bostonians were beginning to patronize the new jewelry shops––and buy American manufactured items. The concept of a jewelry shop instead of an artisan workshop was developing as a place to purchase jewelry, watches, and plate. As Martha Gandy Fales wrote: “By the end of the Federal period, the roots of mass-production and the jewelry industry were spreading in eastern seaboard cities. The conversion of the individual shop to factory operations had begun. The emergence of an American style in jewelry was under way.”

Twycross pieces continued to be valued by their elite clientele in Boston well beyond the life of the firm. For example, in 1823 a large cache of jewelry was stolen from an apartment in the Nahant Hotel in the resort town frequented by wealthy Bostonians. An advertisement offering a reward for its recovery is a snapshot of what jewelry was fashionable and valued at the time. At the top of the list, and the only maker named, was “One Lady’s watch, engine turned with china face, maker’s name S. Twycross & Son, London, No. 11.120.”

Was the Hancock children’s case made by Stephen Twycross? Without a bill, a signature, or a case with a label, it cannot be definitively proved. However, the preponderance of evidence strongly suggests it is by him and that it dates from the mid–1790s to the early 1800s. The value of being able to contextualize the lives and interconnections of people who purchased and wore jewelry from an identifiable jeweler can hopefully serve as a framework for further research.

Addendum:

My research concerning Twycross and his American clients is ongoing. Two more Twycross clients have been identified: John Rowe Parker, a dry goods merchant, and partner in the firm of Smith and Parker, went to London on behalf of his company in 1802 and, having an account with Twycross & Son, he purchased “engraved seals, gold and gilt watches, plated goods, cruet frames, salts, etc.” Another merchant, Abbott Lawrence (1792-1855) “the founder of the New England textile industry” in Lowell, traveled to England in 1817 and purchased a seal and an engraved Crest from Twycross & Davis.

I would especially like to thank Michel Grasyan, James Twycross and Christopher Fance for sharing their Twycross heritage with me and Thomas Wood, John Anderson, and Emese Wood for sharing their Hancock family legacy. And of course, I wish to acknowledge and thank all the people working in museums, archives and libraries who have been so generous and helpful.

Pamela Ehrlich is an independent researcher, archaeologist, and artist.