Portrait of Joan Didion (1934– 2021) by Brigitte Lacombe (1950–), 1996, Lot 2 from the sale. Gelatin silver print, 10 inches square. All photographs courtesy of Stair Galleries, Hudson, New York.

When Stair Galleries, an auction house in the small upstate New York city of Hudson, released its catalogue for the sale of famed author Joan Didion’s personal effects, there was one item that immediately caught our eye: a stack of thirteen blank notebooks, tied up neatly with a piece of cotton twine. The auction estimate was $100–200.

A group of thirteen blank notebooks, Lot 14 from Stair Galleries’ An American Icon: Property from the Collection of Joan Didion sale on November 16, 2022. Smallest 5 1/2 by 3 1/2 inches, largest 6 3/4 by 5 inches.

There was the emotional element to these notebooks—they were owned by one of the greatest nonfiction writers in the pantheon of American literature— and there was the tangible element as objects. What these notebooks would eventually sell for would say a lot about how we, as a society, value the ephemera of celebrity. But as objects? In a world where the digital is regnant and kids no longer even learn cursive writing, what is a bunch of blank notebooks worth?

Lisa Thomas, director of the fine arts department at Stair, added the notebooks to the auction as an afterthought. She and Colin Stair, who represents the fourth generation of his family doing business in auctions and the antiques world, spent a few days in Didion’s Manhattan apartment selecting pieces for the sale. These included a large leather-top partner’s desk. “I was poking around in the drawers of the desk,” Lisa recalls, “and one of the sides was just full of these blank books. I thought young writers would love to have a group of notebooks” tied to such an iconic writer. So she collected them up and split them into three separate lots, including the one that we singled out, Lot 14 in the catalogue.

Nearly as soon as online bidding opened in advance of the live auction, it became apparent that a young writer was unlikely to be able to afford Lot 14. Days before the sale date, the bids on the notebook lots were already in the thousands. The fine art pieces in the sale, impressive regardless of their former owner, were also gaining steam, but it was the objects of daily life that had skyrocketed far beyond their estimates.

This is what we’re interested in: that point at which the practical and the proven give way to emotion. There is something intoxicating about the opportunity to bring home an item that has been in the hands of someone meaningful. Even better than meeting an icon is, it appears, making their desk your desk, making their pot your pot, and making their notebooks your notebooks. Wearing Joan Didion’s sunglasses may change how you see the world. Probably not, but maybe.

Pair of Celine faux-tortoiseshell sunglasses, Lot 5 from An American Icon. Height 2 1⁄4, width 5 1⁄2, depth 5 3/4 inches.

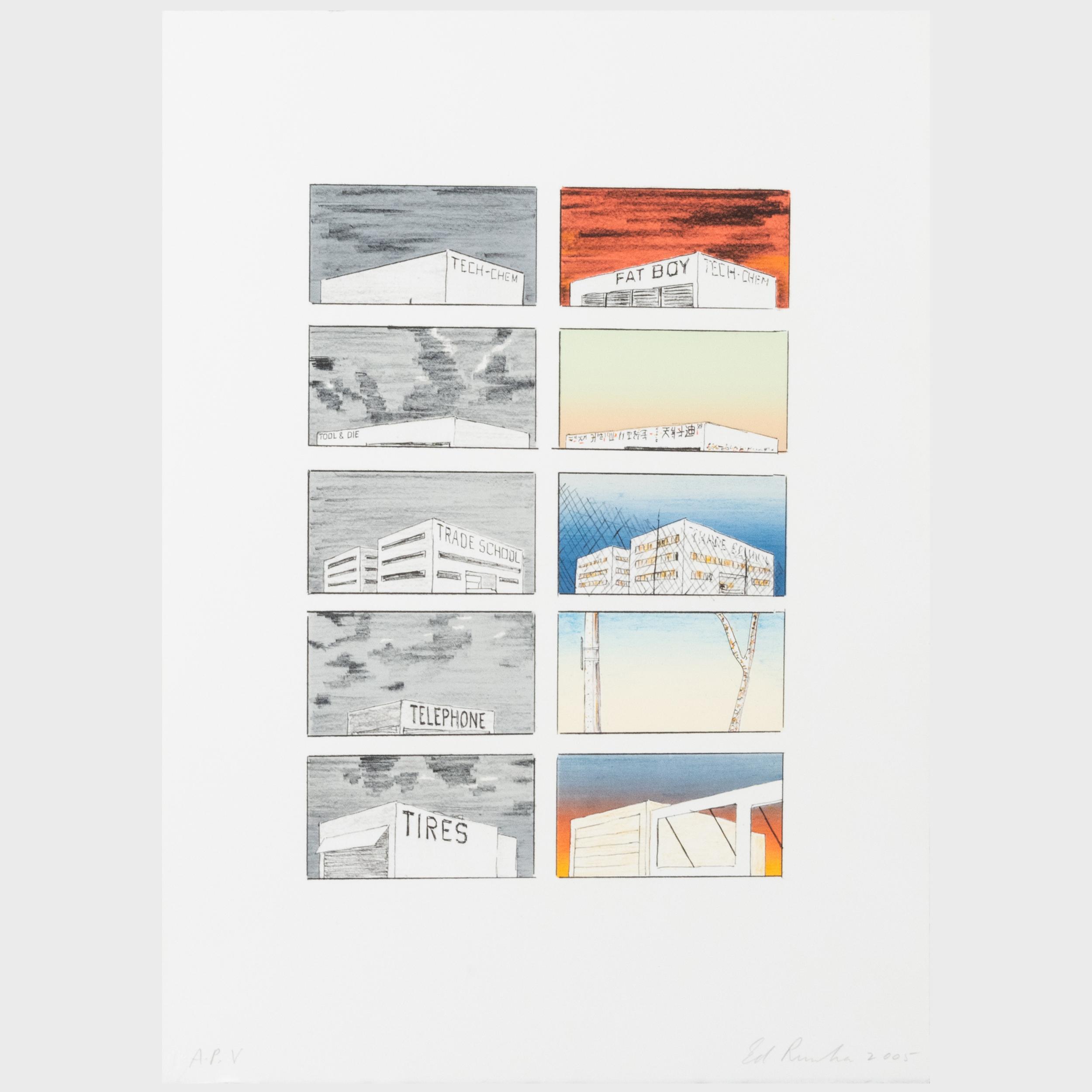

Among the works in Didion’s art collection was a print by famed contemporary Los Angeles artist Ed Ruscha depicting his 2005 Course of Empire series, which was inspired by the Hudson River school’s founding artist Thomas Cole and his series of the same name. The Ruscha piece was tucked out of the way at the sale preview, and we didn’t notice it until Jennifer Greim, a member of the executive staff at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in Catskill, New York, asked over dinner if we’d happened to see it. After that, we returned to the preview and sought the print out.

For those of us who live in the Hudson valley, Cole’s name resonates with much the same timbre as Didion’s. We had explored the contents of Cole’s traveling trunk for a lecture we gave at the Cole site—another object lesson on how the ephemera of life takes on meaning through context. “Saved objects, like Thomas Cole’s hat or rock collection, are akin to sacred relics” says Elizabeth Jacks, director of the Cole site. “We hold on to someone through these inanimate things, imbuing them with magic.” Jacks finds what isn’t given that same treatment equally fascinating, such as the pantry cabinets at the site, which “have survived because of their lack of perceived value.” It made us wonder what Thomas and Stair passed over.

The human desire to be close with the secular divine of creativity is much the same as the fervency with which churches have pursued ownership of a saint’s cloak or a martyr’s shin bone. “This is pure emotion,” Thomas says. The sale at Stair brought in $1.9 million, which will be donated to two charities chosen by the Didion family in her honor.

Course of Empire by Edward Ruscha (1937–), 2005, Lot 42 from the sale. Lithograph on wove paper, 14 by 10 inches (image).

Didion’s faux tortoiseshell Celine-brand sunglasses reached $27,000 on an estimate of $400–800. The desk in which Thomas discovered the stacks of blank notebooks topped out at $60,000 on an estimate of $8,000–12,000, and the Ruscha print reached $20,000. A group of eight books on the Kennedys and Lyndon Johnson from Didion’s shelves sold for $3,250, one of many lots of books not penned by Didion grouped by topic or author.

These things arrived at their new homes, taken out of context and required to stand on their own. They now exist in the world separate from the place and the person that imbued them with meaning. How long, we wonder, will those sunglasses be remembered as Joan Didion’s? How long will that stack of books carry that memory, or will it float away as soon as the buyer’s kid shuffles them on the shelf, disrupting the tableau?

The lot of thirteen blank notebooks that originally caught our eye sold for $9,000, the best deal of the similarly-sized blank notebook lots. The other two went for $11,000 each.

Didion’s partner’s desk, made after 1856 by J. Breuner, Sacramento, California, Lot 11 in the American Icon sale and pictured in situ at the New York apartment she shared with her husband, John Gregory Dunne (1932–2003).